Clogheen, County Tipperary

Clogheen (Irish: Chloichín an Mhargaidh, meaning "Little Stone of the Market")[2][3] is a village in County Tipperary, Ireland. The census of 2016 recorded the population at 478 people.[1]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 1,633 | — |

| 1831 | 1,928 | +18.1% |

| 1841 | 2,049 | +6.3% |

| 1851 | 1,564 | −23.7% |

| 1861 | 1,347 | −13.9% |

| 1871 | 1,317 | −2.2% |

| 1881 | 1,209 | −8.2% |

| 1891 | 915 | −24.3% |

| 1901 | 914 | −0.1% |

| 1911 | 734 | −19.7% |

| 1926 | 641 | −12.7% |

| 1936 | 479 | −25.3% |

| 1946 | 498 | +4.0% |

| 1951 | 505 | +1.4% |

| 1956 | 621 | +23.0% |

| 1961 | 576 | −7.2% |

| 1966 | 572 | −0.7% |

| 1971 | 530 | −7.3% |

| 1981 | 536 | +1.1% |

| 1986 | 502 | −6.3% |

| 1991 | 499 | −0.6% |

| 1996 | 518 | +3.8% |

| 2002 | 550 | +6.2% |

| 2006 | 509 | −7.5% |

| 2016 | 478 | −6.1% |

| [4][5][6][7][8][1] | ||

Clogheen

Chloichín an Mhargaidh | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Clogheen seen from the Knockmealdown Mountains | |

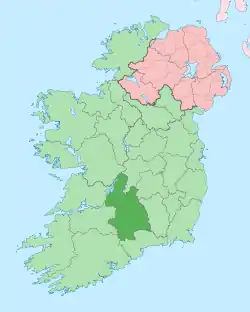

Clogheen Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 52.276°N 7.996°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| County | County Tipperary |

| Dáil Éireann | Tipperary |

| Elevation | 54 m (177 ft) |

| Population (2016)[1] | 478 |

| Dialing code | 0 52, +000 353 (0)52 |

| Irish Grid Reference | S001137 |

| Website | clogheen |

Location

It lies in the Galtee-Vee Valley with the Galtee Mountains to the north and the Knockmealdowns in close proximity to the south. The River Tar which is a tributary of the Suir runs through the village. It is located on the R665 and R668 regional roads. The nearest large towns are Cahir and Mitchelstown, approximately 14 and 20 kilometres away, respectively.

Transport

During the week it is served five times a day in each direction by Bus Éireann route 245 linking it to Clonmel, Mitchelstown, Fermoy and Cork. At the weekend there are three buses each way. There's also a number 18 that runs direct from Dublin city.

History

The first substantial records of the village date from the Cromwellian period, but the village did not come to note until the 18th and 19th centuries. It then became a local centre of trade and commerce. The village takes its modern form from the 19th century with a wide area that was formerly the Market Square (and still named so) and a number of townhouses in the Georgian style. Evidence of its former economic activity exists in the form of a number of ruined mills and accompanying mill-streams in the environs of the village, as well as several large estates.

A former Catholic parish priest of Clogheen, Nicholas Sheehy, is buried at Shanrahan graveyard just outside the village, having been executed in 1766. Sheehy had been a vocal opponent of Anglican Church tithes. When a secret oath-bound society known as the Whiteboys, formed in the parish, elements of the Protestant Ascendancy conspired to make him an example to those who questioned or threatened their powers. After a kangaroo trial in Clonmel, he was hanged for murder and treason, crimes with little basis, no reliable witnesses, and no proof.[9][10]

The stately Shanbally Castle was situated 4.5 kilometres outside the village. It was built circa 1820 for the 1st Viscount Lismore, designed by the architect John Nash, and was demolished by the State in 1960.[11]

Daniel O'Connell addressed a crowd of up to 50,000 people in the town on 28 September 1828, as part of a public demonstration to demand Catholic emancipation.[12]

Lewis' Topographical Dictionary of 1837 notes Clogheen as being located in the barony of Iffa and Offa West and reported that there were 1,928 inhabitants, a military barracks for the accommodation of two troops of cavalry, an extensive brewery, plus seven flour mills in the town and neighbourhood.[13]

Modern times

It is now primarily an agricultural town but it is well linked to the nearby economic centres of Clonmel and Mitchelstown and the larger economies of Cork, Limerick, and Waterford. Clogheen gained national notoriety in 2000 when a former hotel, which was due to house refugees, was damaged by fire in an arson attack.[14] The event reputedly inspired the Gerry Stembridge television film, Black Day at Black Rock.[15] The problems reflected a general upheaval in Irish rural society in which the local population experienced net immigration for the first time in its modern history.

People

- Nan Joyce, the Irish Travellers' rights activist, was born here in 1940.

- Edward Sackville-West

- Reginald Polecarew

Gallery

Junction of R668 and R665 roads in Clogheen

Junction of R668 and R665 roads in Clogheen Shanrahan Graveyard, where Nicholas Sheehy is buried

Shanrahan Graveyard, where Nicholas Sheehy is buried

References

- "Sapmap Area - Settlements - Clogheen". Census 2016. CSO. April 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Clogheen, County Tipperary Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved: 2013-08-12.

- A. D. Mills, 2003, A Dictionary of British Place-Names, Oxford University Press

- Census for post 1821 figures.

- http://www.histpop.org Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700-1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- Madden, Richard Robert (1855). The Literary Life and Correspondence of the Countess of Blessington (Appendix). Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- Moore, Thomas (2008). Emer Nolan (ed.). Memoirs of Captain Rock: The Celebrated Irish Chieftain with Some Account of His Ancestors Written by Himself. Field Day Publications. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-946755-36-3. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- McDonnell, Randal; The Lost Houses of Ireland, A chronicle of great houses and the families who lived there, Weidenfeld & Nicolson(2002)

- Owens,Gary; 'A Moral Insurrection': Faction Fighters, Public Demonstrations and the O'Connellite Campaign, 1828, Irish Historical Studies Vol. 30, No. 120 (Nov., 1997), pp. 513-541 (Nov., 1997)

- Lewis, Samuel; A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837).

- "Man questioned over hotel fire". irishtimes.com. 5 May 2000. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- Sheehan, Helena (2004). The continuing story of Irish television drama: tracking the tiger. Broadcasting and Irish society. 3. Four Courts Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-85182-688-9. Retrieved 1 April 2011.