Close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets that are in proximity to friendly forces and which requires detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movement of these forces and attacks with aerial bombs, glide bombs, missiles, rockets, aircraft cannons, machine guns, and even directed-energy weapons such as lasers.[1]

The requirement for detailed integration because of proximity, fires or movement is the determining factor. CAS may need to be conducted during shaping operations with Special Operations Forces (SOF) if the mission requires detailed integration with the fire and movement of these forces. A closely related subset of air interdiction (AI), battlefield air interdiction, denotes interdiction against units with near-term effects on friendly units, but which does not require integration with friendly troop movements. The term "battlefield air interdiction" is not currently used in U.S. joint doctrine. CAS requires excellent coordination with ground forces; in advanced modern militaries, this coordination is typically handled by specialists such as Joint Fires Observers (JFOs), Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs), and forward air controllers (FACs).

The First World War was the first conflict to make extensive use of CAS, albeit using relatively primitive methods in contrast to later warfare. Even so, it was clear that coordination between aerial and ground forces via radio communication typically made such attacks more effective. Appropriately modified, the British F.E 2b fighter became the first ground-attack aircraft, while Germany produced the first purpose built ground attack aircraft in the form of the Junkers J.I; the Sopwith Camel was another successful early platform. Both the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and the Spring Offensive of 1918 made extensive use of CAS aircraft. The interwar period saw CAS doctrine continue to advance, although theorists and aviators would often clash over its strategic value. Several different conflicts, including the Russo-Polish War, the Spanish Civil War, colonial wars in the Middle East and the Gran Chaco War, were noticeably impacted by CAS operations.

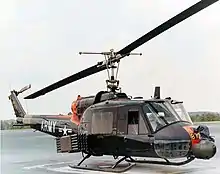

The Second World War marked the universal acceptance of the integration of air power into combined arms warfare. Although the German Luftwaffe was the only force to use CAS at the start of the war, all the major combatants had developed effective air-ground coordination techniques by the conflict's end. New techniques, such as the use of forward air control to guide CAS aircraft and identifying invasion stripes, also emerged at this time, being heavily shaped by the Italian Campaign and the invasion of Normandy. CAS practices continued to advance in further conflicts, including the Korean War and the Vietnam War; major milestones including the introduction of attack helicopters and the creation of aerial gunships, such as the Bell AH-1 Cobra and the Douglas AC-47 Spooky. While many CAS aircraft have been propeller driven, several jet aircraft, such as the A-10 Thunderbolt II (Warthog) and the Su-25 (Frogfoot), have been developed as well.

History

First World War

The use of aircraft in the close air support of ground forces dates back to the First World War, the first conflict to make significant military use of aerial forces.[2] Air warfare, and indeed aviation itself, was still in its infancy—and the direct effect of rifle caliber machine guns and light bombs of the First World War aircraft was very limited compared with the power of (for instance) an average fighter bomber of the Second World War, but CAS aircraft were still able to achieve a powerful psychological impact. The aircraft was a visible and personal enemy—unlike artillery—presenting a personal threat to enemy troops, while providing friendly forces assurance that their superiors were concerned about their situation.

The most successful attacks of 1917–1918 had included planning for co-ordination between aerial and ground units, although it was relatively difficult at this early date to co-ordinate these attacks due to the primitive nature of air-to-ground radio communication. Though most air-power proponents sought independence from ground commanders and hence pushed the importance of interdiction and strategic bombing, they nonetheless recognized the need for close air support.[3]

From the commencement of hostilities in 1914, aviators engaged in sporadic and spontaneous attacks on ground forces, but it was not until 1916 that an air support doctrine was elaborated and dedicated fighters for the job were put into service. By that point, the startling and demoralizing effect that attack from the air could have on the troops in the trenches had been made clear.

At the Battle of the Somme, 18 British armed reconnaissance planes strafed the enemy trenches after conducting surveillance operations. The success of this improvised assault spurred innovation on both sides. In 1917, following the Second Battle of the Aisne, the British debuted the first ground-attack aircraft, a modified F.E 2b fighter carrying 20 lb (9.1 kg) bombs and mounted machine-guns. After exhausting their ammunition, the planes returned to base for refueling and rearming before returned to the battle-zone. Other modified planes used in this role were the Airco DH.5 and Sopwith Camel—the latter was particularly successful in this role.[2]

Aircraft support was first integrated into a battle plan on a large scale at the 1917 Battle of Cambrai, where a significantly larger number of tanks were deployed than previously. By that time, effective anti-aircraft tactics were being used by the enemy infantry and pilot casualties were high, although air support was later judged as having been of a critical importance in places where the infantry had got pinned down.[4]

At this time, British doctrine came to recognize two forms of air support; trench strafing (the modern-day doctrine of CAS), and ground strafing (the modern-day doctrine of air interdiction)—attacking tactical ground targets away from the land battle. As well as strafing with machine-guns, planes engaged in such operations were commonly modified with bomb racks; the plane would fly in very low to the ground and release the bombs just above the trenches.

The Germans were also quick to adopt this new form of warfare and were able to deploy aircraft in a similar capacity at Cambrai. While the British used single-seater planes, the Germans preferred the use of heavier two-seaters with an additional machine gunner in the aft cockpit. The Germans adopted the powerful Hannover CL.II and built the first purpose built ground attack aircraft, the Junkers J.I. During the 1918 Spring Offensive, the Germans employed 30 squadrons, or Schlasta, of ground attack fighters and were able to achieve some initial tactical success.[3] The British later deployed the Sopwith Salamander as a specialized ground attack aircraft, although it was too late to see much action.

During the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of 1918, CAS aircraft functioned as an important factor in ultimate victory. After the British achieved air superiority over the German aircraft sent to aid the Ottoman Turks, squadrons of S.E 5a's and D.H. 4s were sent on wide-ranging attacks against German and Turkish positions near the Jordan river. Combined with a ground assault led by General Edmund Allenby, three Turkish armies soon collapsed into a full rout. In the words of the attacking squadron's official report:

- No 1 Squadron made six heavy raids during the day, dropped three tons of bombs and fired nearly 24,000 machine gun rounds.[2]

Inter-war period

The close air support doctrine was further developed in the interwar period. Most theorists advocated the adaptation of fighters or light bombers into the role. During this period, airpower advocates crystallized their views on the role of air-power in warfare. Aviators and ground officers developed largely opposing views on the importance of CAS, views that would frame institutional battles for CAS in the 20th century.

The inter-war period saw the use of CAS in a number of conflicts, including the Russo-Polish War, the Spanish Civil War, colonial wars in the Middle East and the Gran Chaco War.[2]

The British used air power to great effect in various colonial hotspots in the Middle East and North Africa during the immediate postwar period. The newly formed RAF contributed to the defeat of Afghan forces during the Third Anglo-Afghan War by harassing the enemy and breaking up their formations. Z force, an air squadron, was also used to support ground operations during the Somaliland campaign, in which the "Mad Mullah" Mohammed Abdullah Hassan's insurgency was defeated. Following from these successes, the decision was made to create a unified RAF Iraq Command to use air power as a more cost-effective way of controlling large areas than the use of conventional land forces.[5] It was effectively used to suppress the Great Iraqi Revolution of 1920 and various other tribal revolts.

During the Spanish Civil War German volunteer aviators of the Condor Legion on the Nationalist side, despite little official support from their government, developed close air support tactics that proved highly influential for subsequent Luftwaffe doctrine.

U.S. Marine Corps Aviation was used as an intervention force in support of U.S. Marine Corps ground forces during the Banana Wars, in places such as Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua. Marine Aviators experimented with air-ground tactics and in Haiti and Nicaragua they adopted the tactic of dive bombing.[6]

The observers and participants of these wars would base their CAS strategies on their experience of the conflict. Aviators, who wanted institutional independence from the Army, pushed for a view of air-power centered around interdiction, which would relieve them of the necessity of integrating with ground forces and allow them to operate as an independent military arm. They saw close air support as both the most difficult and most inefficient use of aerial assets.

Close air support was the most difficult mission, requiring identifying and distinguishing between friendly and hostile units. At the same time, targets engaged in combat are dispersed and concealed, reducing the effectiveness of air attacks. They also argued that the CAS mission merely duplicated the abilities of artillery, whereas interdiction provided a unique capability. Ground officers contended there was rarely sufficient artillery available, and the flexibility of aircraft would be ideal for massing firepower at critical points, while producing a greater psychological effect on friendly and hostile forces alike. Moreover, unlike massive, indiscriminate artillery strikes, small aerial bombs would not render ground untrafficable, slowing attacking friendly forces.[3]

Although the prevailing view in official circles was largely indifferent to CAS during the interwar period, its importance was expounded upon by military theorists, such as J. F. C. Fuller and Basil Liddell Hart. Hart, who was an advocate of what later came to be known as 'Blitzkrieg' tactics, thought that the speed of armoured tanks would render conventional artillery incapable of providing support fire. Instead he proposed that:

- actual 'offensive' support must come from an even more mobile artillery moving alongside. For this purpose the close co-operation of low-flying aircraft...is essential[7]

Luftwaffe

As a continental power intent on offensive operations, Germany could not ignore the need for aerial support of ground operations. Though the Luftwaffe, like its counterparts, tended to focus on strategic bombing, it was unique in its willingness to commit forces to CAS. Unlike the Allies, the Germans were not able to develop powerful strategic bombing capabilities, which implied industrial developments they were forbidden to take according to the Treaty of Versailles.[8] In joint exercises with Sweden in 1934, the Germans were first exposed to dive-bombing, which permitted greater accuracy while making attack aircraft more difficult to track by antiaircraft gunners. As a result, Ernst Udet, chief of the Luftwaffe's development, initiated procurement of close support dive bombers on the model of the U.S. Navy's Curtiss Helldiver, resulting in the Henschel Hs 123, which was later replaced by the famous Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. Experience in the Spanish Civil War lead to the creation of five ground-attack groups in 1938, four of which would be equipped with Stukas. The Luftwaffe matched its material acquisitions with advances in the air-ground coordination. General Wolfram von Richthofen organized a limited number of air liaison detachments that were attached to ground units of the main effort. These detachments existed to pass requests from the ground to the air, and receive reconnaissance reports, but they were not trained to guide aircraft onto targets.

These preparations did not prove fruitful in the invasion of Poland, where the Luftwaffe focused on interdiction and dedicated few assets to close air support. But the value of CAS was demonstrated at the crossing of the Meuse River during the Invasion of France in 1940. General Heinz Guderian, one of the creators of the combined-arms tactical doctrine commonly known as "blitzkrieg", believed the best way to provide cover for the crossing would be a continuous stream of ground attack aircraft on French defenders. Though few guns were hit, the attacks kept the French under cover and prevented them from manning their guns. Aided by the sirens attached to Stukas, the psychological impact was disproportional to the destructive power of close air support (although as often as not, the Stukas were used as tactical bombers instead of close air support, leaving much of the actual work to the older Hs 123 units for the first years of the war). In addition, the reliance on air support over artillery reduced the demand for logistical support through the Ardennes. Though there were difficulties in coordinating air support with the rapid advance, the Germans demonstrated consistently superior CAS tactics to those of the British and French defenders. Later, on the Eastern front, the Germans would devise visual ground signals to mark friendly units and to indicate direction and distance to enemy emplacements.

Despite these accomplishments, German CAS was not perfect and suffered from the same misunderstanding and interservice rivalry that plagued other nations' air arms, and friendly fire was not uncommon. For example, on the eve of the Meuse offensive, Guderian's superior cancelled his CAS plans and called for high-altitude strikes from medium bombers, which would have required halting the offensive until the air strikes were complete. Fortunately for the Germans, his order was issued too late to be implemented, and the Luftwaffe commander followed the schedule he had previously worked out with Guderian. As late as November 1941, the Luftwaffe refused to provide Erwin Rommel with an air liaison officer for the Afrika Korps, because it "would be against the best use of the air force as a whole."[3]

German CAS was also extensively used on the Eastern Front during the period 1941–1943. Their decline was caused by the growing strength of the Red Air Force and the redeployment of assets to defend against American and British strategic bombardment. Luftwaffe's loss of air superiority, combined with a declining supply of aircraft and fuel, crippled their ability to provide effective CAS on the western front after 1943.

RAF and USAAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) entered the war woefully unprepared to provide CAS. In 1940 during the Battle of France, the Royal Air Force and Army headquarters in France were located at separate positions, resulting in unreliable communications. After the RAF was withdrawn in May, Army officers had to telephone the War Office in London to arrange for air support. The stunning effectiveness of German air-ground coordination spurred change. On the basis of tests in Northern Ireland in August 1940, Group Captain A. H. Wann RAF and Colonel J.D. Woodall (British Army) issued the Wann-Woodall Report, recommending the creation of a distinct tactical air force liaison officer (known colloquially as "tentacles") to accompany Army divisions and brigades. Their report spurred the RAF to create an RAF Army Cooperation Command and to develop tentacle equipment and procedures placing an Air Liaison Officer with each brigade.[9]

Although the RAF was working on its CAS doctrine in London, officers in North Africa improvised their own coordination techniques. In October 1941, Sir Arthur Tedder and Arthur Coningham, senior RAF commanders in North Africa, created joint RAF-Army Air Support Control staffs at each corps and armored division headquarters, and placed a Forward Air Support Link at each brigade to forward air support requests. When trained tentacle teams arrived in 1942, they cut response time on support requests to thirty minutes.[3] It was also in the North Africa desert that the cab rank strategy was developed.[10] It used a series of three aircraft, each in turn directed by the pertinent ground control by radio. One aircraft would be attacking, another in flight to the battle area, while a third was being refuelled and rearmed at its base. If the first attack failed to destroy the tactical target, the aircraft in flight would be directed to continue the attack. The first aircraft would land for its own refuelling and rearming once the third had taken off. The CAS tactics developed and refined by the British during the campaign in North Africa served as the basis for the Allied system used to subsequently gain victory in the air over Germany in 1944 and devastate its cities and industries.[4]

The use of forward air control to guide close air support (CAS)[11] aircraft, so as to ensure that their attack hits the intended target and not friendly troops, was first used by the British Desert Air Force in North Africa, but not by the USAAF until operations in Salerno.[12] During the North African Campaign in 1941 the British Army and the Royal Air Force established Forward Air Support Links (FASL), a mobile air support system using ground vehicles. Light reconnaissance aircraft would observe enemy activity and report it by radio to the FASL which was attached at brigade level. The FASL was in communication (a two-way radio link known as a "tentacle") with the Air Support Control (ASC) Headquarters attached to the corps or armoured division which could summon support through a Rear Air Support Link with the airfields.[13][14] They also introduced the system of ground direction of air strikes by what was originally termed a "Mobile Fighter Controller" traveling with the forward troops. The controller rode in the "leading tank or armoured car" and directed a "cab rank" of aircraft above the battlefield.[15] This system of close co-operation first used by the Desert Air Force, was steadily refined and perfected, during the campaigns in Italy, Normandy and Germany.

By the time the Italian Campaign had reached Rome, the Allies had established air superiority. They were then able to pre-schedule strikes by fighter-bomber squadrons; however, by the time the aircraft arrived in the strike area, oftentimes the targets, which were usually trucks, had fled.[16] The initial solution to fleeing targets was the British "Rover" system. These were pairings of air controllers and army liaison officers at the front but able to switch communications seamlessly from one brigade to another – hence Rover. Incoming strike aircraft arrived with pre-briefed targets, which they would strike 20 minutes after arriving on station only if the Rovers had not directed them to another more pressing target. Rovers might call on artillery to mark targets with smoke shells, or they might direct the fighters to map grid coordinates, or they might resort to a description of prominent terrain features as guidance. However, one drawback for the Rovers was the constant rotation of pilots, who were there for fortnightly stints, leading to a lack of institutional memory. US commanders, impressed by the British tactics at the Salerno landings, adapted their own doctrine to include many features of the British system.[17]

At the start of the War, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) had, as its principal mission, the doctrine of strategic bombing. This incorporated the unerring belief that unescorted bombers could win the war without the advent of ground troops. This doctrine proved to be fundamentally flawed. However, during the entire course of the war the USAAF top brass clung to this doctrine, and hence operated independently of the rest of the Army. Thus it was initially unprepared to provide CAS, and in fact, had to be dragged "kicking and screaming" into the CAS function with the ground troops. USAAF doctrinal priorities for tactical aviation were, in order, air superiority, isolation of the battlefield via supply interdiction, and thirdly, close air support. Hence, during the North African Campaign, CAS was poorly executed, if at all. So few aerial assets were assigned to U.S. troops that they fired on anything in the air. And in 1943, the USAAF changed their radios to a frequency incompatible with ground radios.

The situation improved during the Italian Campaign, where American and British forces, working in close cooperation, exchanged CAS techniques and ideas. There, the AAF's XII Air Support Command and the Fifth U.S. Army shared headquarters, meeting every evening to plan strikes and devising a network of liaisons and radios for communications. However, friendly fire continued to be a concern – pilots did not know recognition signals and regularly bombed friendly units, until an A-36 was shot down in self-defense by Allied tanks. The expectation of losses to friendly fire from the ground during the planned invasion of France prompted the black and white invasion stripes painted on all Allied aircraft from 1944.[18][19]

In 1944, USAAF commander Lt. Gen. Henry ("Hap") Arnold acquired 2 groups of A-24 dive bombers, the army version of the Navy's SBD-2, in response to the success of the Stuka and German CAS. Later, the USAAF developed a modification of the North American P-51 Mustang with dive brakes – the North American A-36 Apache. However, there was no training to match the purchases. Though Gen. Lesley McNair, commander of Army Ground Forces, pushed to change USAAF priorities, the latter failed to provide aircraft for even major training exercises. Six months before the invasion of Normandy, 33 divisions had received no joint air-ground training.

The USAAF saw the greatest innovations in 1944 under General Elwood Quesada, commander of IX Tactical Air Command, supporting the First U.S. Army. He developed the "armored column cover", where on-call fighter-bombers maintained a high-level of availability for important tank advances, allowing armor units to maintain a high tempo of exploitation even when they outran their artillery assets. He also used a modified antiaircraft radar to track friendly attack aircraft to redirect them as necessary, and experimented with assigning fighter pilots to tours as forward air controllers to familiarize them with the ground perspective. In July 1944, Quesada provided VHF aircraft radios to tank crews in Normandy. When the armored units broke out of the Normandy beachhead, tank commanders were able to communicate directly with overhead fighter-bombers. However, despite the innovation, Quesada focused his aircraft on CAS only for major offensives. Typically, both British and American attack aircraft were tasked primarily to interdiction, even though later analysis showed them to be twice as dangerous as CAS.

XIX TAC, under the command of General Otto P. Weyland used similar tactics to support the rapid armored advance of General Patton's Third Army in its drive across France. Armed reconnaissance was a major feature of XIX TAC close air support, as the rapid advance left Patton's Southern flank open. Such was the close nature of cooperation between the Third Army and XIX TAC that Patton actually counted on XIX TAC to guard his flanks. This close air support from XIX TAC was credited by Patton as having been a key factor in the rapid advance and success of his's Third Army.[20]

The American Navy and Marine Corps used CAS in conjunction with or as a substitute for the lack of available artillery or naval gunfire in the Pacific theater. Navy and Marine F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs used a variety of ordnance such as conventional bombs, rockets and napalm to dislodge or attack Japanese troops using cave complexes in the latter part of the Second World War.[21][22]

Red Air Force

The Soviet Union's Red Air Force quickly recognized the value of ground-support aircraft. As early as the Battles of Khalkhyn Gol in 1939, Soviet aircraft had the task of disrupting enemy ground operations.[23] This use increased markedly after the June 1941 Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.[24] Purpose-built aircraft such as the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik proved highly effective in blunting the activity of the Panzers. Joseph Stalin paid the Il-2 a great tribute in his own inimitable manner: when a particular production factory fell behind on its deliveries, Stalin sent the following cable to the factory manager: "They are as essential to the Red Army as air and bread".[25]

Korean War

From Navy experiments with the KGW-1 Loon, the Navy designation for the German V-1 flying bomb, Marine Captain Marian Cranford Dalby developed the AN/MPQ-14, a system that enabled radar-guided bomb release at night or in poor weather.[26]

Though the Marine Corps continued its tradition of intimate air-ground cooperation in the Korean War, the newly created United States Air Force (USAF) again moved away from CAS, now to strategic bombers and jet interceptors. Though eventually the Air Force supplied sufficient pilots and forward air controllers to provide battlefield support, coordination was still lacking. Since pilots operated under centralized control, ground controllers were never able to familiarize themselves with pilots, and requests were not processed quickly. Harold K. Johnson, then commander of the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (later Army Chief of Staff) commented regarding CAS: "If you want it, you can't get it. If you can get it, it can't find you. If it can find you, it can't identify the target. If it can identify the target, it can't hit it. But if it does hit the target, it doesn't do a great deal of damage anyway."[27]

It is unsurprising, then, that MacArthur excluded USAF aircraft from the airspace over the Inchon Landing in September 1950, instead relying on Marine Aircraft Group 33 for CAS. In December 1951, Lt. Gen. James Van Fleet, commander of the Eighth U.S. Army, formally requested the United Nations Commander, Gen. Mark Clark, to permanently attach an attack squadron to each of the four army corps in Korea. Though the request was denied, Clark allocated many more Navy and Air Force aircraft to CAS. Despite the rocky start, the USAF would also work to improve its coordination efforts. It eventually required pilots to serve 80 days as forward air controllers (FACs), which gave them an understanding of the difficulties from the ground perspective and helped cooperation when they returned to the cockpit. The USAF also provided airborne FACs in critical locations. The Army also learned to assist, by suppressing anti-aircraft fire prior to air strikes.

The U.S. Army wanted a dedicated USAF presence on the battlefield to reduce fratricide, or the harm of friendly forces. This preference led to the creation of the air liaison officer (ALO) position. The ALO is an aeronautically rated officer that has spent a tour away from the cockpit, serving as the primary adviser to the ground commander on the capabilities and limitations of airpower. The Korean War revealed important flaws in the application of CAS. Firstly, the USAF preferred interdiction over fire support while the Army regarded support missions as the main concern for air forces. Then, the Army advocated a degree of decentralization for good reactivity, in contrast with the USAF-favored centralization of CAS. The third point dealt with the lack of training and joint culture, which are necessary for an adequate air-ground integration. Finally, USAF aircraft were not designed for CAS: "the advent of jet fighters, too fast to adjust their targets, and strategic bombers, too big to be used on theatre, rendered CAS much harder to implement".[8]

Vietnam and the CAS role debate

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the US Army began to identify a dedicated CAS need for itself. The Howze Board, which studied the question, published a landmark report describing the need for a helicopter-based CAS requirement.[28] However, the Army did not follow the Howze Board recommendation initially. Nevertheless, it did eventually adopt the use of helicopter gunships and attack helicopters in the CAS role.[29]

Though the Army gained more control over its own CAS due to the development of the helicopter gunship and attack helicopter, the Air Force continued to provide fixed-wing CAS for Army units. Over the course of the war, the adaptation of The Tactical Air Control System proved crucial to the improvement of Air Force CAS.[30] Jets replaced propeller-driven aircraft with minimal issues. The assumption of responsibility for the air request net by the Air Force improved communication equipment and procedures, which had long been a problem. Additionally, a major step in satisfying the Army's demands for more control over their CAS was the successful implementation of close air support control agencies at the corps level under Air Force control.[30] Other notable adaptations were the usage of airborne Forward Air Controllers (FACs), a role previously dominated by FACs on the ground, and the use of B-52s for CAS.[30]

U.S. Marine Corps Aviation was much more prepared for the application of CAS in the Vietnam War, due to CAS being its central mission.[31] One of the main debates taking place within the Marine Corps during the war was whether to adopt the helicopter gunship as a part of CAS doctrine and what its adoption would mean for fixed-wing CAS in the Marine Corps.[32] The issue would eventually be put to rest, however, as the helicopter gunship proved crucial in the combat environment of Vietnam.

Though helicopters were initially armed merely as defensive measures to support the landing and extraction of troops, their value in this role lead to the modification of early helicopters as dedicated gunship platforms. Though not as fast as fixed-wing aircraft and consequently more vulnerable to anti-aircraft weaponry, helicopters could use terrain for cover, and more importantly, had much greater battlefield persistence owing to their low speeds. The latter made them a natural complement to ground forces in the CAS role. In addition, newly developed anti-tank guided missiles, demonstrated to great effectiveness in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, provided aircraft with an effective ranged anti-tank weapon. These considerations motivated armies to promote the helicopter from a support role to a combat arm. Though the U.S. Army controlled rotary-wing assets, coordination continued to pose a problem. During wargames, field commanders tended to hold back attack helicopters out of fear of air defenses, committing them too late to effectively support ground units. The earlier debate over control over CAS assets was reiterated between ground commanders and aviators. Nevertheless, the US Army incrementally gained increased control over its CAS role.[33]

In the mid-1970s, after Vietnam, the USAF decided to train an enlisted force to handle many of the tasks the ALO was saturated with, to include terminal attack control. Presently, the ALO mainly serves in the liaison role, the intricate details of mission planning and attack guidance left to the enlisted members of the Tactical Air Control Party.

Aircraft

Various aircraft can fill close air support roles. Military helicopters are often used for close air support and are so closely integrated with ground operations that in most countries they are operated by the army rather than the air force. Fighters and ground attack aircraft like the A-10 Thunderbolt II provide close air support using rockets, missiles, small bombs, and strafing runs.

During the Second World War, a mixture of dive bombers and fighters were used for CAS missions. Dive bombing permitted greater accuracy than level bombing runs, while the rapid altitude change made it more difficult for antiaircraft gunners to track. The Junkers Ju 87 Stuka is a well known example of a dive bomber built for precision bombing but which was successfully used for CAS. It was fitted with wind-blown whistles on its landing gear to enhance its psychological effect.[34] Some variants of the Stuka were equipped with a pair of 37 mm (1.5 in) Bordkanone BK 3,7 cannons mounted in under-wing gun pods, each loaded with two six-round magazines of armour-piercing tungsten carbide-cored ammunition, for anti-tank operations.[35]

Other than the North American A-36 Apache, a P-51 modified with dive brakes,[36][37] the Americans and British used no dedicated CAS aircraft in the Second World War, preferring fighters or fighter-bombers that could be pressed into CAS service. While some aircraft, such as the Hawker Typhoon and the P-47 Thunderbolt, performed admirably in that role,[38][39] there were a number of compromises that prevented most fighters from making effective CAS platforms. Fighters were usually optimized for high-altitude operations without bombs or other external ordnance – flying at low level with bombs quickly expended fuel. Cannons had to be mounted differently for strafing – strafing required a further and lower convergence point than aerial combat did.

Of the Allied powers that fought in the Second World War, the Soviet Union used specifically designed ground attack aircraft more than the UK and US. Such aircraft included the Ilyushin Il-2, the single most produced military aircraft at any point in world history.[25] The Soviet military also frequently deployed the Polikarpov Po-2 biplane as a ground attack aircraft.[40]

The Royal Navy Hawker Sea Fury fighters and the U.S. Vought F4U Corsair and Douglas A-1 Skyraider were operated in a ground attack capacity during the Korean War.[41][42][43] Outside of the conflict, there were numerous other occasions that the Sea Fury was used as a ground attack platform. Cuban Sea Furies, operated by the Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria ("Revolutionary Air Force"; FAR), were used to oppose the US-orchestrated Bay of Pigs Invasion to attack incoming transport ships and disembarking ground forces alike.[44][45] The A-1 Skyraider also saw later use, especially throughout the Vietnam War.[46]

In the Vietnam War, the United States introduced a number of fixed and rotary wing gunships, including several cargo aircraft that were refitted as gun platforms to serve as CAS and air interdiction aircraft. The first of these to emerge was the Douglas AC-47 Spooky, which was converted from the Douglas C-47 Skytrain/Douglas DC-3. Some commentators have remarked on the high effectiveness of the AC-47 in the CAS role.[47][48] The USAF developed several other platforms following on from the AC-47, including the Fairchild AC-119 and the Lockheed AC-130.[49] The AC-130 has had a particularly lengthy service, being used extensively during the War in Afghanistan, the Iraq War and the US military intervention in Libya during the early twenty-first century.[50][51] Multiple variants of the AC-130 have been developed and it has continued to be modernised, including the adoption of various new armaments.[52][53]

Usually close support is thought to be only carried out by fighter-bombers or dedicated ground-attack aircraft, such as the A-10 Thunderbolt II (Warthog) or Su-25 (Frogfoot), but even large high-altitude bombers have successfully filled close support roles using precision-guided munitions. During Operation Enduring Freedom, the lack of fighter aircraft forced military planners to rely heavily on US bombers, particularly the B-1B Lancer, to fill the CAS role. Bomber CAS, relying mainly on GPS guided weapons and laser-guided JDAMs has evolved into a devastating tactical employment methodology and has changed US doctrinal thinking regarding CAS in general. With significantly longer loiter times, range, and weapon capacity, bombers can be deployed to bases outside of the immediate battlefield area, with 12-hour missions being commonplace since 2001. After the initial collapse of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, airfields in Afghanistan became available for continuing operations against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. This resulted in a great number of CAS operations being undertaken by aircraft from Belgium (F-16 Fighting Falcon), Denmark (F-16), France (Mirage 2000D), the Netherlands (F-16), Norway (F-16), the United Kingdom (Harrier GR7s, GR9s and Tornado GR4s) and the United States (A-10, F-16, AV-8B Harrier II, F-15E Strike Eagle, F/A-18 Hornet, F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, UH-1Y Venom).

The use of information technology to direct and coordinate precision air support has increased the importance of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in using CAS. Laser, GPS, and battlefield data transfer are routinely used to coordinate with a wide variety of air platforms able to provide CAS. Recent doctrine[54] reflects the increased use of electronic and optical technology to direct targeted fires for CAS. Air platforms communicating with ground forces can also provide additional aerial-to-ground visual search, ground-convoy escort, and enhancement of command and control (C2), assets which can be particularly important for low intensity conflict.[55]

See also

- Artillery observer

- Attack aircraft

- Counter-insurgency aircraft, a specific type of CAS aircraft

- Flying Leathernecks

- Forward air control

- Light Attack/Armed Reconnaissance

- Pace-Finletter MOU 1952

- Tactical bombing, a general term for the type of bombing that includes CAS and air interdiction

References

Citations

- Close Air Support. United States Department of Defense, 2014.

- Hallion (1990), Airpower Journal, p. 8.

- House (2001), Combined Arms Warfare.

- Hallion, Richard P. (2010). Strike From the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1910–1945. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817356576. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Boyle, Andrew. Trenchard Man of Vision p. 371.

- Corum & Johnson, Small Wars, pp. 23-40.

- Mearsheimer, John J. (2010). Liddell Hart and the Weight of History. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801476310. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Tenenbaum, Elie (October 2012). "The Battle over Fire Support: The CAS Challenge and the Future of Artillery" (PDF). Focus stratégique. Institut français des relations internationales. 35 bis. ISBN 978-2-36567-083-8.

- Delve 1994, p. 100.

- Strike from Above: The History of Battlefield Air Attack 1911–1945. pp. 181–182.

- "Joint Air Operations Interim Joint warfare Publication 3–30" (PDF). MoD. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-08.

CAS in defined as air action against targets that are in proximity to friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of these forces

- Matthew G. St. Clair, Major, USMC (February 2007). "The Twelfth US Air Force Tactical and Operational Innovations in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, 1943–1944" (PDF). Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama.

The use of forward air controllers (FAC) was another innovative technique employed during Operation Avalanche. FACs were first employed in the Mediterranean by the British Desert Air Force in North Africa but not by the AAF until operations in Salerno. This type of C2 was referred to as "Rover Joe" by the United States and "Rover David" or "Rover Paddy" by the British.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Air power at the Battlefront: Allied Close Air Support in Europe, 1943–45 Ian Gooderson p26

- Post, Carl A. (2006). "Forward air control: a Royal Australian Air Force innovation". Air Power History.

- "RAF & Army Co-operation" (PDF). Short History of the Royal Air Force. RAF. p. 147. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-06.

- Hallion, Richard. P (1989). Strike from the sky : the history of battlefield air attack, 1911-1945. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-87474-452-0. OCLC 19590167.

- Charles Pocock. "THE ANCESTRY OF FORWARD AIR CONTROLLERS". Forward Air Controllers Association. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013.

fundamental feature of the system was use of waves of strike aircraft, with pre-briefed assigned targets but required to orbit near the line of battle for 20 minutes, subject to Rover preemption and use against fleeting targets of higher priority or urgency. If the Rovers did not direct the fighter-bombers, the latter attacked their pre-briefed targets. US commanders, impressed by British at the Salerno landings, adapted their own doctrine to include many features of the British system, leading to differentiation of British "Rover David", US "Rover Joe" and British "Rover Frank" controls, the last applying air strikes against fleeting German artillery targets.

- Janus, Allan (6 June 2014). "The Stripes of D-Day". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Shaw, Frederick J. "Army Air Forces and the Normandy Invasion, April 1 to July 12, 1944". U.S. Air Force – via Rutgers University.

- Spires 2002.

- Barber 1946, Table 2.

- Whistling Death: The Chance-Vought F4U Corsair. Warfare History Network. 16 December 2018.

- Coox 1985, p. 663.

- Austerslått, Tor Willy. "Ilyushin Il-2." Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine break-left.org, 2003. Retrieved: 27 March 2010.

- Hardesty 1982, p. 170.

- Krulak, First to Fight, pp. 113-119.

- Blair (1987), Forgotten War, p. 577.

- "General HH Howze (Obit)". Nytimes.com. 18 December 1998. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- "Transforming the Force: The 11th Air Assault Division (Test) from 1963–1965". dtic.mil. p. 29.

- Schlight, John (2003). Help From Above: Air Force Close Air Support of the Army, 1946-1973. Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Publication Program. p. 300. ISBN 0-16-051552-1.

- Callahan, Lieutenant Colonel Shawn (2009). Close Air Support and the Battle for Khe Sanh. Quantico, VA: History Division, United States Marine Corps. pp. 25–27.

- Krueger, Colonel S.P. (May 1966). "Attack or Defend". Marine Corps Gazette. 50: 47.

- "Interservice Rivalry and Airpower in the Vietnam War – Chapter 5" (PDF). Carl.army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Griehl 2001, p. 63

- Griehl 2001, p. 286

- Grunehagen 1969, p. 60.

- Kinzey 1996, p. 22.

- Thomas and Shores 1988, pp. 23–26.

- Dunn, Carle E. (LTC). "Army Aviation and Firepower". Archived 2008-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Army, May 2000. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- Gordon 2008, p. 285.

- Darling 2002, pp. 51–52.

- Kinzey 1998, p. 12.

- "U.S. Alert to New Red Air Attacks". Aviation Week. Vol. 61 no. 5. 2 August 1954. p. 15.

- Mario E. "Bay of Pigs: In the Skies Over Girón". 2000, (18 March 2014.)

- Cooper, Tom. "Clandestine US Operations: Cuba, 1961, Bay of Pigs". 2007, (18 March 2014.)

- Dorr and Bishop 1996, pp. 34–35.

- Corum, James S. and Johnson, Wray R. "Airpower in Small Wars: Fighting Insurgents and Terrorists." Kansas University Press: 2003. ISBN 0-7006-1239-4. p. 337.

- "AC-47 Factsheet". Archived from the original on 11 October 2014.

- "Hurlburt Field: AC-119 Shadow". Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. United States Air Force, 7 July 2008. Retrieved: 8 May 2012.

- Kreisher, Otto (1 July 2009). "Gunship Worries". airforcemag.com.

- McGarry, Brendan (28 March 2011), Coalition Isn't Coordinating Strikes With Rebels, US Says, Bloomberg, archived from the original on 9 October 2014, retrieved 8 March 2017

- "A Spookier Spooky, 30 mm at a Time? Nope". Defense Industry Daily. 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Michael Sirak with Marc Schanz, "Spooky Gun Swap Canceled". Air Force Magazine, October 2008, Volume 91, Number 10, p. 24.

- "Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Close Air Support (CAS)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. 3 September 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Haun (2006), Air & Space Power Journal.

Bibliography

- Blair, Clay (1987). The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953. New York: Times Books/Random House..

- Coox, Alvin D.: Nomonhan: Japan Against Russia, 1939. Two volumes; 1985, Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1160-7

- Corum, James S.; Wray R. Johnson (2003). Airpower in Small Wars – Fighting Insurgents and Terrorists. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1240-8..

- Darling, Kev. Hawker Sea Fury (Warbird Tech Vol. 37). North Branch, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58007-063-9.

- Delve, Ken. The Source Book of the RAF. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1994. ISBN 1-85310-451-5.

- Dorr, Robert F. and Chris Bishop. Vietnam Air War Debrief. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-874023-78-6.

- Gordon, Yefim. "Soviet Air Power in World War 2". Hersham-Surrey, UK: Midland Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-304-4.

- Griehl, Manfred (2001). Junker Ju 87 Stuka. London/Stuttgart: Airlife/Motorbuch. ISBN 1-84037-198-6..

- Gruenhagen, Robert W. Mustang: The Story of the P-51 Mustang. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1969. ISBN 0-668-03912-4.

- Haun, LtCol Phil M., USAF (Fall 2006). "The Nature of Close Air Support in Low Intensity Conflict". Air & Space Power Journal. Retrieved 11 February 2007..

- Hallion, Dr. Richard P. (Spring 1990). "Battlefield Air Support: A Retrospective Assessment". Airpower Journal. U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2018..

- Hardesty, Von. Red Phoenix: The Rise of Soviet Air Power, 1941–1945. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1982. ISBN 1-56098-071-0.

- House, Jonathan M. (2001). Combined Arms Warfare in the Twentieth Century. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1081-2..

- "Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Close Air Support (CAS)" (PDF). Joint Publication 3-09.3 (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. 3 September 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Kinzey, Bert. F4U Corsair Part 2: F4U-4 Through F4U-7: Detail and Scale Vol 56. Carrolton, Texas: Squadron Signal Publications, 1998. ISBN 1-888974-09-5.

- Kinzey, Bert. P-51 Mustang Mk In Detail & Scale: Part 1; Prototype through P-51C. Carrollton, Texas: Detail & Scale Inc., 1996. ISBN 1-888974-02-8.

- Krulak, Victor H. (1984). First To Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-785-2..

- Spires, David, Air Power for Patton's Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command in the Second World War (Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2002.

- Tenenbaum, Elie (October 2012). "The Battle over Fire Support: The CAS Challenge and the Future of Artillery" (PDF). Focus stratégique. Institut français des relations internationales. 35 bis. ISBN 978-2-36567-083-8..

- Thomas, Chris and Christopher Shores. The Typhoon and Tempest Story. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1988. ISBN 0-85368-878-8.

External links

- Can Our Jets Support the Guys on the Ground? – Popular Science

- The Forward Air Controller Association

- The ROMAD Locator The home of the current ground FAC

- Operation Anaconda: An Airpower Perspective – Close air support during Operation Anaconda, United States Airforce, 2005.