Sukhoi Su-25

The Sukhoi Su-25 Grach (Russian: Грач (rook); NATO reporting name: Frogfoot) is a single-seat, twin-engine jet aircraft developed in the Soviet Union by Sukhoi. It was designed to provide close air support for the Soviet Ground Forces. The first prototype made its maiden flight on 22 February 1975. After testing, the aircraft went into series production in 1978 at Tbilisi in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

| Su-25 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A Russian Air Force Su-25 | |

| Role | Close air support |

| National origin | Soviet Union / Russia |

| Manufacturer | Sukhoi |

| First flight | 22 February 1975 (T8) |

| Introduction | 19 July 1981 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Air Force Bulgarian Air Force Ukrainian Air Force Korean People's Army Air Force See Operators for others |

| Produced | 1978–present |

| Number built | Over 1,000 |

| Variants | Sukhoi Su-28 |

Early variants included the Su-25UB two-seat trainer, the Su-25BM for target-towing, and the Su-25K for export customers. Some aircraft were being upgraded to Su-25SM standard in 2012. The Su-25T and the Su-25TM (also known as the Su-39) were further developments, not produced in significant numbers. The Su-25, and the Su-34, were the only armoured, fixed-wing aircraft in production in 2007.[1] Su-25s are in service with Russia, other CIS members, and export customers.

The type has seen combat in several conflicts during its more than 30 years in service. It was heavily involved in the Soviet–Afghan War, flying counter-insurgency missions against the Mujahideen. The Iraqi Air Force employed Su-25s against Iran during the 1980–88 Iran–Iraq War. Most were later destroyed or flown to Iran in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. The Georgian Air Force used Su-25s during the Abkhazia War from 1992 to 1993. The Macedonian Air Force used Su-25s against Albanian insurgents in the 2001 Macedonia conflict and, in 2008, Georgia and Russia both used Su-25s in the Russo-Georgian War. African states, including the Ivory Coast, Chad, and Sudan have used the Su-25 in local insurgencies and civil wars. Recently the Su-25 has seen service in the Russian intervention in the Syrian Civil War and the clashes of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Development

In early 1968, the Soviet Ministry of Defence decided to develop a specialised shturmovik armoured assault aircraft in order to provide close air support for the Soviet Ground Forces. The idea of creating a ground-support aircraft came about after analysing the experience of ground-attack (shturmovaya) aviation during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s.[2] The Soviet fighter-bombers in service or under development at the time (Su-7, Su-17, MiG-21 and MiG-23) did not meet the requirements for close air support of the army.[2] They lacked essential armour plating to protect the pilot and vital equipment from ground fire and missile hits, and their high flight speeds made it difficult for the pilot to maintain visual contact with a target. Having taken into account these problems, Pavel Sukhoi and a group of leading specialists in the Sukhoi Design Bureau started preliminary design work in a comparatively short period of time, with the assistance of leading institutes of the Ministry of the Aviation Industry and the Ministry of Defence.[3]

In March 1969, a competition was announced by the Soviet Air Force that called for designs for a new battlefield close-support aircraft. Participants in the competition were the Sukhoi design bureau and the design bureaus of Yakovlev, Ilyushin and Mikoyan.[4] Sukhoi finalised its "T-8" design in late 1968, and began in work on the first two prototypes (T8-1 and T8-2) in January 1972. The T8-1, the first airframe to be assembled, was completed on 9 May 1974. Another source says November 1974. However, it did not make its first flight until 22 February 1975, after a long series of test flights by Vladimir Ilyushin. The Su-25 surpassed its main competitor in the Soviet Air Force competition, the Ilyushin Il-102, and series production was announced by the Ministry of Defence.[5][6]

During flight-testing phases of the T8-1 and T8-2 prototypes' development, the Sukhoi Design Bureau's management proposed that the series production of the Su-25 should start at Factory No. 31 in Tbilisi, Soviet Republic of Georgia, which at that time was the major manufacturing base for the MiG-21UM "Mongol-B" trainer. After negotiations and completion of all stages of the state trials, the Soviet Ministry of Aircraft Production authorised manufacture of the Su-25 at Tbilisi, allowing series production to start in 1978.[7]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, several Su-25 variants appeared, including modernised versions, and variants for specialised roles. The most significant designs were the Su-25UB dual-seat trainer, the Su-25BM target-towing variant, and the Su-25T for antitank missions. In addition, an Su-25KM prototype was developed by Georgia in co-operation with Israeli company Elbit Systems in 2001, but so far this variant has not achieved much commercial success. As of 2007, the Su-25 was the only armoured aircraft still in production.[1]

The Russian Air Force, which operates the largest number of Su-25s, planned to upgrade older aircraft to the Su-25SM variant, but funding shortfalls had slowed the progress; by early 2007 only seven aircraft had been modified.[8]

Design

Overview

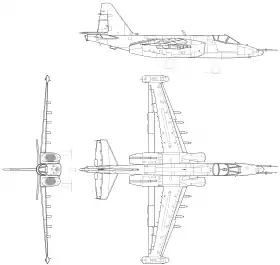

The Su-25 has a conventional aerodynamic layout with a shoulder-mounted trapezoidal wing and a traditional tailplane and rudder. Several metals are used in the construction of the airframe: 60% aluminium, 19% steel, 13.5% titanium, 2% magnesium alloy and 5.5% other materials.[9]

All versions of the Su-25 have a metal cantilever wing, of moderate sweep, high aspect ratio and equipped with high-lift devices. The wing consists of two cantilever sections attached to a central torsion box, forming a single unit with the fuselage. The air brakes are housed in fairings at the tip of each wing. Each wing has five hardpoints for weapons carriage, with the attachment points mounted on load-bearing ribs and spars.[10] Each wing also features a five-section leading edge slat, a two-section flap and an aileron.

The flaps are mounted by steel sliders and rollers, attached to brackets on the rear spar. The trapezoidal ailerons are near the wingtips.[11] The fuselage of the Su-25 has an ellipsoidal section and is of semi-monocoque, stressed-skin construction, arranged as a longitudinal load-bearing framework of longerons, beams and stringers, with a transverse load-bearing assembly of frames.[9] The one-piece horizontal tailplane is attached to the load-bearing frame at two mounting points.[11]

Early versions of the Su-25 were equipped with two R-95Sh non-afterburning turbojets, in compartments on either side of the rear fuselage. The engines, sub-assemblies and surrounding fuselage are cooled by air provided by the cold air intakes on top of the engine nacelles. A drainage system collects oil, hydraulic fluid residues and fuel from the engines after flight or after an unsuccessful start. The engine control systems allows independent operation of each engine.[11] The latest versions (Su-25T and TM) are equipped with improved R-195 engines.[12]

The cannon is in a compartment beneath the cockpit, mounted on a load-bearing beam attached to the cockpit floor and the forward fuselage support structure. The nose is fitted with distinctive twin pitot probes and hinges up for service access.[9]

Cockpit

The pilot flies the aircraft by means of a centre stick and left hand throttles. The pilot sits on a Zvezda K-36 ejection seat (similar to the Sukhoi Su-27) and has standard flight instruments. At the rear of the cockpit is a six-millimetre-thick (0.24 in) steel headrest, mounted on the rear bulkhead. The cockpit has a bathtub-shaped armoured enclosure of welded titanium sheets, with transit ports in the walls. Guide rails for the ejection seat are mounted on the rear wall of the cockpit.[9]

The canopy hinges open to the right and the pilot enters using the flip-down ladder. Once inside, the pilot sits low in the cockpit, protected by the bathtub assembly, which makes for a cramped cockpit. Visibility from the cockpit is limited, being a trade-off for improved pilot protection. Rearwards visibility is poor and a periscope is fitted on top of the canopy to compensate.[13]

A folding ladder built into the left fuselage provides access to the cockpit as well as to the top of the aircraft.

Avionics

The base model Su-25 incorporates a number of key avionics systems. It has no TV guidance but includes a distinctive nose-mounted laser rangefinder, that is thought to provide for laser-based target finding.[13][14] A DISS-7 doppler radar is used for navigation; the Su-25 can fly at night, in visual and instrument meteorological conditions.

The Su-25 often has radios installed for air-to-ground and air-to-air communications, including an SO-69 identification-friend-or-foe (IFF) transponder. The aircraft's self-defence suite includes various measures, such as flare and chaff dispensers capable of launching up to 250 flares and dipole chaff. Hostile radar uses are guarded against via an SPO-15 radar warning receiver.

An airtight avionics compartment is behind the cockpit and in front of the forward fuel tank.

The newer Su-25TM and Su-25SM models have an upgraded avionics and weapons suite, resulting in improved survivability and combat capability.[15]

Operational history

Soviet–Afghan War

The first Soviet Air Forces Su-25 unit was the 200th Independent Attack Squadron, initially based at Sitalcay air base in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. The first eleven aircraft arrived at Sitalchay in May 1981.[16]

On 19 July 1981, the 200th Independent Attack Squadron was reassigned to Shindand Airbase in western Afghanistan, becoming the first Su-25 unit deployed to that country. Its main task was to conduct air strikes against mountain military positions and structures controlled by the Afghan rebels.[17] Another Soviet Su-25 unit was the 368th Attack Aviation Regiment, which was formed on 12 July 1984, at Zhovtneve in Ukraine.[18] It was soon also moved east to conduct operations over Afghanistan.

Over the course of the Soviet–Afghan War, Su-25s launched a total of 139 guided missiles of all types against Mujahideen positions. On average, each aircraft performed 360 sorties a year, a total considerably higher than that of any other combat aircraft in Afghanistan. By the end of the war, nearly 50 Su-25s were deployed at Afghan airbases, carrying out a total of 60,000 sorties. Between the first deployment in 1981 and the end of the war in 1989, 21–23 aircraft were lost in combat operations, with up to nine destroyed on the ground while parked.[17][19]

Iran–Iraq War

The Su-25 also saw combat during the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–88. The first Su-25s were commissioned by the Iraqi Air Force in 1987 and performed approximately 900 combat sorties towards the end of the war, carrying out the bulk of Iraqi air attack missions. During the most intense combat of the war, Iraqi Su-25s performed up to 15 sorties per day, each. In one recorded incident, an Iraqi Su-25 was shot down by an Iranian, Hawk surface-to-air missile, but the pilot managed to eject. This was the only confirmed, successful Iranian shootdown of an Iraqi Su-25. After the war, Saddam Hussein decorated all of the Iraqi Air Force's Su-25 pilots with the country's highest military decoration.[17]

Gulf War

During the Gulf War of 1991, the air superiority of the coalition forces was so great that the majority of Iraqi Su-25s did not even manage to get airborne. On 25 January 1991, seven Iraqi Air Force Su-25s fled from Iraq and landed in Iran.[20]

On the evening of 6 February 1991, two US Air Force F-15C Eagle fighters of the 53rd Tactical Fighter Squadron, operating from Al Kharj Air Base in Saudi Arabia, intercepted a pair of Iraqi MiG-21s and a pair of Su-25s. All four Iraqi aircraft were shot down, with both Su-25s coming down in the desert not far from the Iraqi border with Iran. This was the Iraqi Su-25s' only air combat of the war.[17]

Abkhazian War

The Georgian government used Su-25s in 1992–93 against Abkhaz separatists during the First Abkhazian War.[21] A Georgian Air Force Su-25 was shot down over Nizhnaya Eshera on July 4, 1993 by an 9K34 Strela-3 MANPADS.[22][23] Another Georgian Su-25 was shot down on 13 July 1993 with a 9K32 Strela-2 MANPADS,[24] while another Su-25 was downed by friendly fire by a ZU-23-2 on 4 July.[24] The Russian Air Force also lost an Su-25 during war, the aircraft crashed due to a pilot's mistake while providing CAS for Abkhaz forces.[24]

First Chechen War

Russian Su-25s were employed during the First Chechen War. Together with other Russian Air Force air assets, they achieved air supremacy for Russian Forces. On 29 November 1994, attacking all four Chechen military bases, Russian Su-25 from the 368th OShAP destroyed up to 266 Chechen aircraft on the ground, mostly not airworthy.[25] The Air Force's deployed assets performed around 9,000 air sorties, with around 5,300 being strike sorties during the Chechen campaign between 1994 and 1996. The 4th Russian Air Army had 140 Su-17Ms, Su-24s and Su-25s in the war zone supported by an A-50 AWACS aircraft. The employed munitions were generally unguided S-5, S-8, and S-24 rockets, as well as FAB-250 and FAB-500 bombs, while only 2.3% of the strikes used precision-guided Kh-25ML missiles, KAB-500L and KAB-500KR smart bombs when weather conditions were suitable.[26] Russian forces were not able to properly take advantage of the achieved air supremacy due to obsolete air tactics that focused the Air Force on useless tasks in this type of war such as Combat Air Patrols.[27] The Russian air losses were low since no integrated air defense was fielded by the Chechens.[28]

On 4 February 1995, a Russian Su-25 was shot down by ZSU-23-4 Shilka antiaircraft fire over Belgatoi Gekhi, five kilometers southeast of Grozny. The pilot, Maj. Nikolay Bairov, ejected but died impacting the ground as his parachute did not deploy on time. Another Su-25 piloted by Lt. Col. Evgeny Derkulsky was damaged by ground fire on the same day, but managed to land at Mozdok air base, where the aircraft was repaired.[25] On 5 May 1995, another Russian Su-25 was downed near Serzhen-Yurt by 12.7 mm fire while on a low-altitude patrol. The pilot, Col. Vladimir Sarabeyev, was killed.[29]

On 4 April 1996, another Su-25 fell either to ZU-23-2 fire while either making a reconnaissance flight or attacking the village of Goiskoye. The pilot, Maj. Alexander Matvienko, ejected and was recovered by a friendly helicopter returning to the airbase in Khankala, Grozny.[30] On 5 May 1996, a two-seat Su-25UB was downed with an 9K34 Strela-3 MANPADS near the village of Mairtup while on reconnaissance. Both pilots, Col. Igor Sviryidov and Maj. Oleg Isayev, were killed in the crash. It was the fourth Su-25 shot down and fifth Russian fixed wing aircraft lost, since the start of the war in December 1994.[28][31]

Second Chechen War

Russian Air Force Su-25s were extensively used during the Second Chechen War in particular during the first phase when Russian forces were invading the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.[32] Up to seven Russian Su-25s were lost,[28] one to hostile fire: on 4 October 1999, a Su-25 was shot down by a MANPADS during a reconnaissance mission over the village of Tolstoy-Yurt killing its pilot. The wings of the aircraft were put on a pedestal in the central square in Grozny.[30][33]

Ethiopian–Eritrean War

Su-25 attack aircraft were used by the Ethiopian Air Force to strike Eritrean targets. On 15 May 2000, An Ethiopian Su-25 was shot down by an Eritrean Air Force MiG-29, killing the pilot.[34]

2001 insurgency in the Republic of Macedonia

Su-25s were used by the Macedonian Air Force during the conflict against Albanian separatists. Beginning on 24 June 2001, the aircraft made multiple attack runs against separatist positions. The most successful operation took place on 10 August 2001, in the village of Raduša, when Su-25s attacked Albanian militants who had ambushed and killed 16 Macedonian soldiers over the previous two days.[35]

War in Darfur

Sudan has used Su-25s in attacks on rebel targets and possibly civilians in Darfur.[36]

Ivorian-French clashes

During the Ivorian Civil War, Su-25s were used by government forces to attack rebel targets. On 6 November 2004, at least one Ivorian Sukhoi Su-25 attacked a unit of France's Unicorn peacekeeping forces stationed in Bouaké at 1300, killing nine peacekeepers and a U.S. development worker, and wounding 37 soldiers.[37] Shortly afterwards, the French military retaliated by attacking the air base in Yamoussoukro and destroyed the Ivorian air force, including its two Su-25s.[38][39][40]

2008 Russia–Georgia war

.jpg.webp)

In August 2008, Su-25s were used by both Georgia and Russia during the 2008 Russia–Georgia war. Su-25s of the Georgian Air Force participated in providing air support for troops during Battle of Tskhinvali and launched bombing raids on targets in South Ossetia.[41] Russian military Su-25s struck Georgian forces in South Ossetia, and undertook air raids on targets in Georgia.[42] The Russian military officially confirmed the loss of three Su-25 aircraft to the Georgian air defense, though the Moscow Defense Brief suggests four.[43][44] The three Russian aircraft were reportedly downed by Georgian Buk-M1 air defence units.[45] Georgian Su-25s were able to operate at night.[45] In early August 2008, Russian Su-25s attacked the Tbilisi Aircraft Manufacturing plant, where the Su-25 is produced, dropping bombs on the factory's airfield.[46]

Iran

On 1 November 2012, two Iranian Su-25s fired cannon bursts at a USAF MQ-1 Predator drone 30 km (19 mi; 16 nmi) off the Iranian coast. The Iranian government has claimed that the drone violated its airspace.[47][48][49]

2014–2015 conflict in Ukraine

Ukrainian armed forces deployed aircraft over insurgent Eastern regions starting in spring 2014. On 26 May 2014, Ukrainian Su-25s supported Mi-24 helicopters during a military operation to regain control over the airport in Donetsk, during which the Su-25s fired air to ground rockets.[50] On 2 July 2014, one Ukrainian Su-25 crashed due to a technical fault.[51][52][53]

On 16 July 2014, an Su-25 was shot down, with Ukrainian officials stating that a Russian MiG-29 shot it down using a R-27T missile.[54][55] Russia denied these allegations.[56]

On 23 July 2014, two Su-25s were shot down in the Donetsk region of Ukraine. A spokesperson for the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine said the aircraft were shot down by missiles fired from Russia.[57]

On 29 August 2014, a Ukrainian Su-25 was shot down by pro-Russian rebels. The Ukrainian authorities said the downing was due to a Russian missile without clarifying if they mean Russian made or fired by Russian forces. The pilot managed to eject safely. On the same day, pro-Russian rebels claimed the downing of up to four Su-25s.[58][59]

On 9 February 2015, the pro-Russian forces indirectly acknowledged, for the first time, with a reference to a Ukrainian media source, their use of Su-25 against Ukrainian forces during the fighting near Debaltsevo.[60]

2014 Northern Iraq offensive

On 29 June 2014, it was reported that Iraq claimed to have received the first batch of second hand Su-25s ordered from Russia in order to fight Sunni rebels of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. An Iraqi defense ministry source claimed the aircraft would be in service "within three to four days", despite the fact that the Iraqis require technical help and parts to make them operational, and the fact that the Russian made aircraft are incompatible with the Iraqi Air force's inventory of American made Hellfire missiles.[61][62]

The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps Air Force delivered seven Su-25s on 1 July 2014, the majority of which were ex-Iraqi aircraft from the Gulf War.[63] They were quickly pushed into combat, performing air raids as early as the beginning of August 2014 and later expanding their area of operation.[64][65]

Iraqi Su-25s flew the bulk of the sorties against the Islamic State, with 3562 missions between June 2014 and December 2017, by which time ISIS had lost control of all the territory it formerly controlled in Iraq. That compares to 514 sorties flown by the Iraqi fleet of F-16IQ fighters.[66]

Military intervention in Syria

In September 2015, it was reported that at least a dozen Su-25 were deployed by Russia to an airfield near Latakia, Syria, to support the Russian forces there who were taking part in the Syrian offensive against ISIL.[67] On 2 October 2015, Russian Su-24M and Su-25 attack aircraft destroyed an ISIL command post in the Idlib province, while Su-34 and Su-25 aircraft eliminated an ISIL fortified bunker in the Hama province. By 15 March 2016, with the scaling down of Russian presence in Syria, Russian Su-25s had performed over 1,600 sorties in Syria while dropping 6,000 bombs.[68]

On 3 February 2018 a Russian Su-25 was shot down over Idlib by rebel fighters who used a MANPADS. A Syrian militant said that the pilot, Roman Filipov, ejected safely but killed himself with a grenade to avoid capture.[69][70][71][72]

2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

On 29 September 2020, Armenian Defense Ministry claimed that an Armenian Air Force Su-25 was shot down by a Turkish Air Force F-16 killing the pilot. However Turkey denied the allegation.[73][74][75]

On 4 October 2020, an Azerbaijani Air force Su-25 aircraft was shot down, by Armenian forces, probably by a 9K33 Osa while targeting Armenian positions in Fuzuli. The pilot, Col. Zaur Nudiraliyev died in the crash. Azerbaijani officials acknowledged the loss in December 2020,[76][77] while disclosing a major role of manned aviation being hidden during the active phase of the conflict with more than 600 airstrikes by manned aviation from 27 September 2020 to 9 November 2020, with the Su-25 fleet, tasked with the critical role of suppression and destruction of the enemy air defense among others.[78]

Variants

Su-25

The basic version of the aircraft was produced at Factory 31, at Tbilisi, in the Soviet Republic of Georgia. Between 1978 and 1989, 582 single-seat Su-25s were produced in Georgia, not including aircraft produced under the Su-25K export program. This variant of the aircraft represents the backbone of the Russian Air Force's Su-25 fleet, currently the largest in the world.[7] The aircraft experienced a number of accidents in operational service caused by system failures attributed to salvo firing of weapons. In the wake of these incidents, use of its main armament, the 240 mm S-24 rocket, was prohibited. In its place, the FAB-500 500 kg (1,100 lb) general-purpose high-explosive bomb became the primary armament.[7]

Su-25K

The basic Su-25 model was used as the basis for a commercial export variant, known as the Su-25K (Komercheskiy). This model was also built at Factory 31 in Tbilisi, Georgia. The aircraft differed from the Soviet Air Force version in certain minor details concerning internal equipment. A total of 180 Su-25K aircraft were built between 1984 and 1989.[7]

Su-25UB

The Su-25UB trainer (Uchebno-Boyevoy) was drawn up in 1977. The first prototype, called "T-8UB-1", was rolled out in July 1985 and its maiden flight was carried out at the Ulan-Ude factory airfield on 12 August of that year.[7] By the end of 1986, 25 Su-25UBs had been produced at Ulan-Ude before the twin-seater completed its State trials and officially cleared for service with the Soviet Air Force.[79]

It was intended for training and evaluation flights of active-duty pilots, and for training pilot cadets at Soviet Air Force flying schools. The performance did not differ substantially from that of the single-seater. The navigation, attack, sighting devices and weapons-control systems of the two-seater enabled it to be used for both routine training and weapons-training missions.[80]

Su-25UBK

From 1986 to 1989, in parallel with the construction of the main Su-25UB combat training variant, the Ulan-Ude plant produced the so-called "commercial" Su-25UBK, intended for export to countries that bought the Su-25K, and with similar modifications to that aircraft.[81]

Su-25UBM

The Su-25UBM is a twin seat variant that can be used as an operational trainer, but also has attack capabilities, and can be used for reconnaissance, target designation and airborne control. Its first flight was on 6 December 2008 and it was certified in December 2010. It will enter operational use with the Russian Air Force later. The variant has a Phazotron NIIR Kopyo radar and Bars-2 equipment on board. Su-25UBM's range is believed to be 1,300 km (810 mi) and it may have protection against infra-red guided missiles (IRGM), a minimal requirement on today's battle fields where IRGMs proliferate.[82]

Su-25UTG

The Su-25UTG (Uchebno-Trenirovochnyy s Gakom) is a variant of the Su-25UB designed to train pilots in takeoff and landing on a land-based simulated carrier deck, with a sloping ski-jump section and arrester wires. The first one flew in September 1988, and approximately 10 were produced.[83] About half remained in Russian service after 1991; they were used on Russia's sole aircraft carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov. This small number of aircraft were insufficient to meet the training needs of Russia's carrier air group, so a number of Su-25UBs were converted into Su-25UTGs. These aircraft being distinguished by the alternative designation Su-25UBP (Uchebno-Boyevoy Palubny)—the adjective palubnyy meaning "deck", indicating that these aircraft have a naval function.[84] Approximately 10 of these aircraft are currently operational in the Russian Navy as part of the 279th Naval Aviation Regiment.[85]

Su-25BM

The Su-25BM (Buksirovshchik Misheney) is a target-towing variant of the Su-25 whose development began in 1986. The prototype, designated T-8BM1, successfully flew for the first time on 22 March 1990, at Tbilisi. After completion of the test phase, the aircraft was put into production.[84]

The Su-25BM target-tower was designed to provide towed target facilities for training ground forces and naval personnel in ground-to-air or naval surface-to-air missile systems. It is powered by an R-195 engine and equipped with an RSDN-10 long-range navigation system, an analogue of the Western LORAN system.[84]

Su-25T

The Su-25T (Tankovy) is a dedicated antitank version, which has been combat-tested with notable success in Chechnya.[15] The design of the aircraft is similar to the Su-25UB. The variant was converted to one-seater, with the rear seat replaced by additional avionics.[86] It has all-weather and night attack capability. In addition to the full arsenal of weapons of the standard Su-25, the Su-25T can employ the KAB-500Kr TV-guided bomb and the semi-active laser-guided Kh-25ML.[15] Its enlarged nosecone houses the Shkval optical TV and aiming system with the Prichal laser rangefinder and target designator. It can also carry Vikhr laser-guided, tube-launched missiles, which is its main antitank armament. For night operations, the low-light TV Merkuriy pod system can be carried under the fuselage. Three Su-25Ts prototypes were built in 1983–86 and 8 production aircraft were built in 1990.[87] With the introduction of a definitive Russian Air Force Su-25 upgrade programme, in the form of Stroyevoy Modernizirovannyi, the Su-25T programme was officially canceled in 2000.[88]

Su-25TM (Su-39)

A second-generation Su-25T, the Su-25TM (also designated Su-39), has been developed with improved navigation and attack systems, and better survivability. While retaining the built-in Shkval of Su-25T, it may carry Kopyo (rus. "Spear") radar in the container under fuselage, which is used for engaging air targets (with RVV-AE/R-77 missiles) as well as ships (with Kh-31 and Kh-35 antiship missiles). The Russian Air Force has received 8 aircraft as of 2008.[86] Some of the improved avionics systems designed for T and TM variants have been included in the Su-25SM, an interim upgrade of the operational Russian Air Force Su-25, for improved survivability and combat capability.[15] The Su-25TM, as an all-inclusive upgrade programme has been replaced with the "affordable" Su-25SM programme.[88]

Su-25SM

.jpg.webp)

The Su-25SM (Stroyevoy Modernizirovannyi) is an "affordable" upgrade programme for the Su-25, conceived by the Russian Air Force in 2000. The programme stems from the attempted Su-25T and Su-25TM upgrades, which were evaluated and labeled as over-sophisticated and expensive. The SM upgrade incorporates avionics enhancements and airframe refurbishment to extend the Frogfoot's service life by up to 500 flight hours or 5 years.[88]

The Su-25SM's all-new PRnK-25SM "Bars" navigation/attack suite is built around the BTsVM-90 digital computer system, originally planned for the Su-25TM upgrade programme. Navigation and attack precision provided by the new suite is three times better of the baseline Su-25 and is reported to be within 15 m (49 ft) using satellite correction and 200 m (660 ft) without it.[88]

A new KA1-1-01 Head-Up Display (HUD) was added providing, among other things, double the field of view of the original ASP-17BTs-8 electro-optical sight. Other systems and components incorporated during the upgrade include a Multi-Function Display (MFD), RSBN-85 Short Range Aid to Navigation (SHORAN), ARK-35-1 Automatic Direction Finder (ADF), A-737-01 GPS/GLONASS Receiver, Karat-B-25 Flight Data Recorder (FDR), Berkut-1 Video Recording System (VRS), Banker-2 UHF/VHF communication radio, SO-96 Transponder and a L150 "Pastel" Radar Warning Receiver (RWR).[88]

The R-95sh engines have been overhauled and modified with an anti-surge system installed. The system is designed to improve the resistance of the engine to ingested powders and gases during gun and rocket salvo firing.[88]

The combination of reconditioned and new equipment, with increased automation and self-test capability has allowed for a reduction of pre- and post-flight maintenance by some 25 to 30%. Overall weight savings are around 300 kg (660 lb).[88]

Su-25SM weapon suite has been expanded with the addition of the Vympel R-73 highly agile air-to-air missile (albeit without helmet mounted cueing and only the traditional longitudinal seeker mode) and the S-13T 130 mm rockets (carried in five-round B-13 pods) with blast-fragmentation and armour-piercing warheads. Further, the Kh-25ML and Kh-29L Weapon Employment Profiles have been significantly improved, permitting some complex missile launch scenarios to be executed, such as: firing two consecutive missiles on two different targets in a single attack pass. The GSh-30-2 autocannon (250-round magazine) has received three new reduced rate-of-fire modes: 750, 375 and 188 rounds per minute. The Su-25SM was also given new BD3-25 under-wing pylons.[88]

The eventual procurement programme is expected to include between 100 and 130 kits, covering 60 to 70 percent of the Russian Air Force active single-seat fleet, as operated in the early 2000s.[88] On 21 February 2012, Air Force spokesman Col. Vladimir Drik said that Russia will continue to upgrade its Su-25 attack aircraft to Su-25SM version, which has a significantly better survivability and combat effectiveness. The Russian Air Force then had over 30 Su-25SMs in service and plans to modernize about 80 Su-25s by 2020, Drik said.[89][90] By March 2013, over 60 aircraft are to be upgraded.[90][91] In February 2013, ten new Su-25SMs were delivered to the Air Force southern base,[92][93] where operational training is being conducted.[94] During the period 2005–2015, more than 80 aircraft were upgraded.[95]

Since early 2014, the Guards Aviation Division Attack Aviation Regiment of the Southern Military District in the Krasnodar region received 16 advanced Su-25SMs. Nine more were delivered in 2018,[96][97][98] eight more in early 2019[99][100][101] and four more in early 2020.[102][103]

Since 2018, the Aerospace Forces [VKS] have been receiving Su-25SM3s, and a total of 25 aircraft have already been delivered as of June 2019. Unlike the baseline Su-25 and its incrementally upgraded variant, the Su-25SM, both of which have a rather outdated Klen-PS laser target designator in the nose, the Su-25SM3 has been upgraded with the new SOLT-25 electro-optics nose module. The SOLT-25 provides 16× zoom and features a laser range finder and target designator, thermal imager, TV channels, and the ability to track moving targets in all weather up to 8 km away. In addition, the Su-25SM3 comes with the Vitebsk-25 protection suite, which integrates a set of Zakhvat forward and rearward facing missile approach warning ultraviolet sensors, the L-150-16M Pastel radar homing and warning system, two UV-26M 50 mm chaff dispensers, and a pair of wing-mounted L-370-3S radar jamming pods. Furthermore, the Su-25SM3 has been upgraded with the new PrNK-25SM-1 Bars targeting-and-navigation system and the KSS-25 communication system with Banker-8-TM-1 antenna.[104]

The Su-25SM3s have SVP-24 navigation and bombing aids that allow stand off precision bombing as a result of experience in Syria.[105]

Su-25KM

The Su-25KM (Kommercheskiy Modernizirovannyy), nicknamed "Scorpion", is an Su-25 upgrade programme announced in early 2001 by the original manufacturer, Tbilisi Aircraft Manufacturing in Georgia, in partnership with Elbit Systems of Israel. The prototype aircraft made its maiden flight on 18 April 2001 at Tbilisi in full Georgian Air Force markings.[106] The aircraft uses a standard Su-25 airframe, enhanced with advanced avionics including a glass cockpit, digital map generator, helmet-mounted display, computerised weapons system, complete mission pre-plan capability, and fully redundant backup modes. Performance enhancements include a highly accurate navigation system, pinpoint weapon delivery systems, all-weather and day/night performance, NATO compatibility, state-of-the art safety and survivability features, and advanced onboard debriefing capabilities complying with international requirements.[106] It has the ability to use Mark 82 and Mark 83 laser-guided bombs and air-to-air missiles, the short-range Vympel R-73.[107]

Su-28

The Sukhoi Su-28 (also designated Su-25UT – Uchebno-Trenirovochnyy) is an advanced basic jet trainer, built on the basis of the Su-25UB as a private initiative by the Sukhoi Design Bureau. The Su-28 is a light aircraft designed to replace the Czechoslovak Aero L-39 Albatros. Unlike the basic Su-25UB, it lacks a weapons-control system, built-in cannon, weapons hardpoints, and engine armour.[108]

Other

- Su-25R (Razvedchik) – a tactical reconnaissance variant designed in 1978, but never built.[109]

- Su-25U3 (Uchebnyy 3-myestny) – also known as the "Russian Troika", was a three-seat basic trainer aircraft. The project was suspended in 1991 due to lack of funding.[109]

- Su-25U (Uchebnyy) – a trainer variant of Su-25s produced in Georgia between 1996 and 1998. Three aircraft were built in total, all for the Georgian Air Force.[109]

- Su-25M1/Su-25UBM1 – Su-25 and Su-25UB exemplars slightly modernized by Ukrainian Air Force, at least nine modernized (eight single-seat and one two-seat). Upgrades include a new navigation system, enhanced survivability, more accurate weapon delivery and other minor changes.[110]

- Ge-31 is an ongoing Georgian program of Tbilisi Aircraft Manufacturing aiming at producing a renewed version of Su-25 without Russian components and parts.[111]

Operators

Notable accidents

The Su-25 has been involved in the following notable aviation accidents.

- An Su-25K of the Air Force of the Democratic Republic of the Congo disappeared in December 2006 during a routine rebasing operation and no wreckage was ever found.[112]

- Another Congolese Su-25K crashed on 30 June 2007 during an Independence Day display, near the city of Kisangani, killing the pilot. Investigations revealed that the crash was due to an engine failure.[112]

- An Su-25 of the Russian Air Force exploded in mid-air on 20 March 2008 during a live firing exercise over the Primorsky Krai, 143 km (89 mi) from Vladivostok, killing the pilot. Further investigations revealed that the aircraft was downed by a missile accidentally launched by a wingman. After the accident, all Russian Su-25s were grounded until the investigation was concluded.[113]

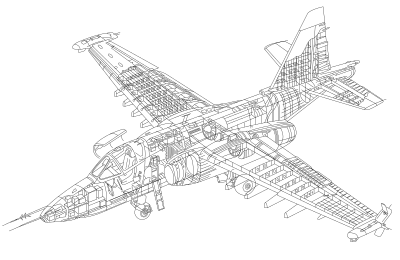

Specifications (Su-25/Su-25K, late production)

- 1: SPM-17A cannon

- 2: Air brakes

- 3: Electronic countermeasures

- 4: Laser Station Maple-PS

- 5: Avionics

- 6: Identification friend or foe system

- 7: Pitot tube

- 8: Drogue parachute

- 9: Fuel tanks

- 10: Main landing gear

- 11: K-36L ejection seat

- 12: Bulletproof glass

- 13: Periscope

- 14: Turbojet

- 15: Air intake

- 16: RSBN Short Range Navigation System

- 17: PA-7 Pitot tube

- 18: Front landing gear

- 19: Canopy

- 20: TSA-17 Sight

- 21: Hinged ladder

- 22: Longeron

- 23: Flaps

- 24: Leading edge slats

- 25: Empennage, including rudder

- 26: Aileron

- 27: ASO-2V infrared countermeasures

- 28: SPO-15 radar warning receiver

- 29: Tail flaps

- 30: CDD-25 hardpoints

- 31: AAP-60 Starter engines[114]

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004,[115] Sukhoi,[116] deagel.com,[117] airforce-technology.com[118]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 15.53 m (50 ft 11 in) (including nose probe)

- Wingspan: 14.36 m (47 ft 1 in)

- Height: 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 33.7 m2 (363 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 9,800 kg (21,605 lb)

- Gross weight: 14,440 kg (31,835 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 19,300 kg (42,549 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Soyuz/Tumansky R-195 turbojet engine, 44.18 kN (9,930 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 975 km/h (606 mph, 526 kn)

- Maximum speed: Mach 0.79

- Range: 1,000 km (620 mi, 540 nmi)

- Combat range: 750 km (470 mi, 400 nmi) at sea level with 4,400 kg (9,700 lb) of ordnance and two external fuel tanks

- Service ceiling: 7,000 m (23,000 ft)

- g limits: +6.5

- Rate of climb: 58 m/s (11,400 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns:

- 1 × 30 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-30-2 autocannon with 250 rounds

- SPPU-22 gun pods for 2 × 23 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-23 autocannons with 260 rounds

- Hardpoints: 11 hardpoints with a capacity of up to 4,400 kg (9,700 lb) of stores,with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets:

- UB-32A rocket pods for S-5 rockets

- B-8M1 rocket pods for S-8 rockets

- S-13

- S-24

- S-25

- Missiles:

- Bombs:

- BETAB-500 concrete-penetrating bomb[119]

- FAB-250 general-purpose bomb

- FAB-500 GP bomb

- FAN-500 bomb[119]

- KAB-500KR TV-guided bomb[120]

- ZAB-500 incendiary bomb[119]

- Other:

- Rockets:

Avionics

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

Notes

Citations

- Gordon and Dawes 2004.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 6–7.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 8.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 11.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 23–41.

- "Sukhoi Company (JSC) – Airplanes – Military Aircraft – Su-25К – Historical background". sukhoi.org. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 42–46.

- "Force report: Russian Air Force." Air Forces Monthly, July 2007, pp. 78–86.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 73–75.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 77.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 79–82.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 111.

- Goebel, Greg. The Sukhoi Su-25 "Frogfoot" Archived 5 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, airvectors.net website, 1 July 2011.

- Su-25К specification substituted, taken from "Sukhoi Company (JSC) – Airplanes – Military Aircraft – Su-25К – Aircraft performance." Archived 22 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Sukhoi.org. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 111–126.

- "Historical background." Archived 18 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Sukhoi.org. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 133–49.

- Rozendaal, Frank, Rene van Woezik and Tieme Festner. 'Bear tracks in Germany: The Soviet Air Force in the former German Democratic Republic: Part 1." Air International, October 1992, p. 210.

- "The Sukhoi Su-25 "Frogfoot"". airvectors.net. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Iran bolsters Su-25 fleet". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2013.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Jane's Defence Weekly, 13 September 2006.

- "Siege of Sukhumi." Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Time Magazine, 4 October 1993.

- "2005". ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Cooper, Tom. "Georgia and Abkhazia, 1992–1993: the War of Datchas". ACIG.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "CIS region - Авиация в локальных конфликтах". Skywar.ru. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Chechenya - Air force in local wars". skywar.ru. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "The Air University page" (PDF). Maxwell AFB. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Military Learning Between the Chechen Wars." Archived 13 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Sras.org. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- "Caucasian diamond traffic – Part 2." Archived 12 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine civilresearch.org. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- "Frontal and Army Aviation in the Chechen Conflict". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Aircraft by type." Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ejection-history.org.uk. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- "Rebels Down Russian Plane In Chechnya." Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 6 May 1996. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Sukhoi Su-25 'Frogfoot'." Vectorsite.net. Retrieved: 26 January 2012. Archived 6 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Russia/Chechnya – Terrorism Leads To War." Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Greatdreams.com. Retrieved: 26 January 2012.

- "Ethiopia." acig.org. Retrieved: 10 August 2010.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 100–102.

- "Disputed attack jets seen by U.N. envoys in Darfur." Archived 29 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- "Nine French soldiers killed in Cote d'Ivoire." Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine People's Daily Online, 8 November 2004.

- "France attacks Ivorian airbase." BBC News, 6 November 2004.

- "Ivory Coast seethes after attack." Archived 17 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 7 November 2004.

- Cooper, Tom with Alexander Mladenov. "Cote d'Ivoire, since 2002." Archived 17 July 2012 at Archive.today ACIG Journal, 5 August 2004.

- "N. Ossetia president: Georgian planes bomb out humanitarian aid convoy for S. Ossetia." Interfax, 8 August 2008.

- "Fighting rages in Georgian separatist capital." Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 8 August 2008.

- "General staff recognized the loss of two more aircraft." Archived 17 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine RU: Lenta, 11 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008. English translation Archived 30 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Barabanov, Mikhail. "The August War between Russia and Georgia." Moscow Defense Brief. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- "Russia's rapid reaction." International Institute for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 11 November 2012. Archived 26 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Nowak, David (for Associated Press). "Russian air raid targets Tbilisi factory; fighting continues to rage in South Ossetia".] Newser, 10 August 2008.

- Stewart, Phil. "Iranian warplanes fired on U.S. drone over Gulf: Pentagon." Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 5 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- "Iranian fighters 'fired on US drone in Gulf' – Middle East." Archived 10 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Al Jazeera English, 8 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Starr, Barbara. "First on CNN: Iranian jets fire on U.S. drone." Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine CNN, 8 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- "The Aviationist » Impressive Videos of the Ukrainian Air Strikes on Donetsk". The Aviationist. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "В Днепропетровске разбился штурмовик Су-25". Lenta.ru. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- "Штурмовик Су-25 разбился в Днепропетровске из-за неисправности, пилот жив". Interfax-Ukraine. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- "Su-25 attack aircraft crashes in Dnipropetrovsk". KyivPost. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "SBU releases more conversations implicating Russia in shooting down Malaysia Airlines flight (VIDEO, TRANSCRIPT)". KyivPost. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Spokesman for National Security and Defense Council Information Center: Malaysian Flight MH-17 was outside the range of Ukraine's surface to air defense systems - Ukraine Crisis Media Center - UACRISIS.ORG". uacrisis.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Russia Rejects 'Absurd' Accusation Over Downed Ukrainian Jet". rferl.org. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- Katersky, Aaron (23 July 2014). "Ukraine Says Two Jets Downed By Missiles Fired From Russia". ABC News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Ukrainian fighter jet shot down by Russian missile in Donbas". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "ASN Aircraft accident 29-AUG-2014 Sukhoi Su-25M1 08 YELLOW". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "МОЛНИЯ: Ополчение применило авиацию под Дебальцево — 2 штурмовика СУ-25 нанесли удар по позициям 40-го батальона, — источник". rusvesna.su. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Iraq receives Russian fighter jets to fight rebels" Archived 13 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 29 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Iraq takes delivery of Russian fighter jets" Archived 3 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Al Jazeera. 29 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Jonathan Marcus (2 July 2014), "'Iranian attack jets deployed' to help Iraq fight Isis", BBC News, archived from the original on 2 July 2014, retrieved 2 July 2014

- "Who Bombed ISIS Militants On August 7?". Business Insider. 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Iraqi Su-25s debut in combat ISIS in the North". AIRheads↑FLY. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Trevithick, Joseph. "Iraq's An-32 Cargo Planes Turned Bombers Flew Nearly Twice As Many Strikes As its F-16s". thedrive.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Pentagon releases satellite images of Russian aircraft in Syria". unian.info. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- "TASS: Military & Defense - Russia's Su-25 warplanes dropped 6,000 bombs during operation in Syria". TASS. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Im Nordwesten Syriens: Rebellen schießen russischen Kampfjet ab - und töten Piloten". Spiegel Online. 3 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Pilot killed after Syrian rebels down Russian warplane". cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Ensor, Josie; Bodner, Matthew (5 February 2018). "Russian pilot shouts 'this is for our guys' as he blows himself up to evade capture in Syria". Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Russian pilot blows himself up to avoid capture by jihadists". nypost.com. 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Турецкий истребитель сбил Су-25 ВВС Армении". RIA. 29 September 2020.

- "Son dakika haberleri! İletişim Başkanı Fahrettin Altun: Türkiye Ermeni uçağını vurmadı - Dünya Haberleri". www.haberturk.com.

- "Armenia says its fighter jet 'shot down by Turkey'". BBC News. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Əsir düşməmək üçün "Su-25" döyüş təyyarəsini düşmən səngərinə çırpan şəhid polkovnik Zaur Nudirəliyev VİDEO" (in Azerbaijani). 27 December 2020.

- "Armenian air defenses shot down Azerbaijani Su-25 during Karabakh conflict, pilot was killed: media". Al-Masdar News. 27 December 2020.

- Herk, Hans van. "Combat missions of the Azerbaijani Air Force in the Second Karabakh War". www.scramble.nl.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 54.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 50–51.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 56.

- Karnozov, Vladimir. "Sukhoi's Su-25UBM completes state acceptance trials." Archived 23 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine FlightGlobal, 20 December 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, p. 59.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 60–71.

- "Russian Military Analysis on Su-25". Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine warfare.ru. Retrieved: 18 June 2007.

- Bangash 2008, p. 270.

- Donald 2004, pp. 234–237.

- Mladenov, Alexander (January 2013). "Armoured Workhorse". Air Forces Monthly (298): 68–74.

- John Pike. "Su-25SM FROGFOOT (SUKHOI)". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Russia to Field New Ground Attack Jet." RIA Novosti. Retrieved: 17 June 2012. Archived 20 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Russian) Archived 12 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 11 November 2012.

- "Около 10 новейших самолетов Су-25СМ3 поступили на авиабазу в ЮВО | РИА Новости". Ria.ru. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- "Около 10 новейших самолетов Су-25СМ3 поступили на авиабазу в ЮВО | РИА Новости". Ria.ru. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Летчики ЮВО осваивают новейшие Су-25СМ3 в ночное время | РИА Новости". Ria.ru. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- "Russia upgrades Su-25 assault jets - part 1". airrecognition.com.

- "Авиаполк ЮВО получил 16 штурмовиков Су-25СМ3 с начала года – Еженедельник "Военно-промышленный курьер"". vpk-news.ru. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Штурмовую авиацию ЮВО пополнили шесть Су-25СМ3". www.armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Звено модернизированных штурмовиков Су-25СМ пополнило боевой состав авиации ЮВО". www.armstrade.org. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Авиаполк ЮВО в Ставропольском крае пополнился новейшими штурмовиками Су-25СМ3 "Суперграч"". www.armstrade.org. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Авиационный полк ЮВО в Ставропольском крае пополнился тремя штурмовиками Су-25СМ3". www.armstrade.org.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Авиационный полк ЮВО на Кубани пополнился новейшим штурмовиком Су-25СМ3". armstrade.org.

- "Russia's Su-25SM3 'deep upgrade' programme gains pace and scope - Jane's 360". www.janes.com. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- {{cite web|url=https://www.rbth.com/science-and-tech/326290-russias-modified-su-25sm3-flying%7Cwebsite=www.rbth.com%7Caccess-date=1 August 2020}

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 103–132.

- "Su-25KM Scorpion (It is made in Georgia)." on YouTube Retrieved: 30 June 2011.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 56–57.

- Gordon and Dawes 2004, pp. 70–72.

- "Su-25." Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine ukrinform.ua. Retrieved: 3 August 2010.

- "Georgia starts assembling reconfigured Su-25 attack aircraft without Russian components". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Congolese fighter jet crashes during display". Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2012. Reuters, 30 June 2007. Retrieved: 17 June 2008.

- "Su-25 jet 'downed by wingman' in last week's crash." Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine RIA Novosti, 26 March 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- Bedretdinov 2002.

- Jackson 2003, pp. 403–405.

- "Sukhoi Company (JSC) – Airplanes – Military Aircraft – Su-25К – Aircraft performance". Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- "Su-25". deagel.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Su-25 (Su-28) Frogfoot Close-Support Aircraft - Airforce Technology". airforce-technology.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Mladenov, Alexander (20 September 2013). Sukhoi Su-25 Frogfoot. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472804785. Retrieved 26 November 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Su-25 FROGFOOT Grach (Rook)". FAS.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Russia wants to join the ISIS battle in Iraq Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Shawn Snow, Military Times, 2017-12-06

- Su-25 (Su-28) Frogfoot Close-Support Aircraft: Countermeasures Archived 17 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Air Force Technology; accessed 2017-12-07

Bibliography

- Bangash, M.Y.H. Shock, Impact and Explosion: Structural Analysis and Design. Berlin: Springer, 2008. ISBN 978-3-540-77067-1.

- Bedretdinov, Ilʹdar (2002). Штурмовик Су-25 и его модификации [The Su-25 and its modifications] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Bedretdinov i Ko. ISBN 978-5-901668-01-6.

- Donald, David. The Pocket Guide to Military Aircraft and the World's Airforces. London: Hamlyn, 2004. ISBN 978-0-681-03185-2.

- Donald, David and Daniel J. March. "Sukhoi Su-25 'Frogfoot'." Modern Battlefield Warplanes. London: AIRtime Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-880588-76-5.

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Frawley, Gerald. "Sukhoi_Su-25". The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002/2003. Fishwick, Act: Aerospace Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- Gordon, Yefim (2003). Sukhoi Su-25. New York: IP Media, Inc., 2005. ISBN 1-932525-02-5.

- Gordon, Yefim (July 2007). Sukhoi Su-25: The Soviet Union's Tank-Buster. Midland Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-254-2.

- Gordon, Yefim and Alan Dawes. Sukhoi Su-25 Frogfoot: Close Air Support Aircraft. London: Airlife, 2004. ISBN 1-84037-353-9.

- Jackson, Paul. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group, 2003. ISBN 0-7106-2537-5.

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-875671-50-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Su-25К at Sukhoi.org

- Su-25 at GlobalSecurity.org

- Su-25 at Russia Military Analysis

- Su-25UB Combat Trainer at the Wayback Machine (archived 9 January 2008)