Codex Climaci Rescriptus

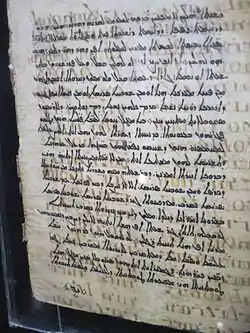

Codex Climaci rescriptus is a collective palimpsest manuscript consisting of several individual manuscripts (eleven) underneath with Christian Palestinian Aramaic texts of the Old and New Testament as well as two apocryphal texts, including the Dormition of the Mother of God, and is known as Uncial 0250 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering) with a Greek uncial text of the New Testament and overwritten by Syriac treatises of Johannes Climacus (hence name of the codex): the scala paradisi and the liber ad pastorem.[1] Paleographically the Greek text has been assigned to the 7th or 8th century, and the Aramaic text to the 6th century. It originates from Saint Catherine’s Monastery going by the News Finds of 1975.[2] Formerly it was classified as lectionary manuscript, with Gregory giving the number ℓ 1561 to it.[3]

| New Testament manuscript | |

| |

| Name | Codex Climaci Rescriptus |

|---|---|

| Text | Gospel of Matthew 21:27–31 |

| Date | 6th century |

| Script | Syriac, Christian Palestinian Aramaic |

| Found | Saint Catherine’s Monastery Sinai |

| Now at | The Green Collection |

| Cite | A. S. Lewis, Codex Climaci rescriptus, Horae semiticae, VIII (1909), p. 42; Christa Müller-Kessler and M. Sokoloff, The Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period. Gospels, Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, IIA (1998), p. 21. |

| Size | 23 cm by 18.5-15.5 cm |

| Type | mixed |

| Category | III |

Description

The codex is a 146 folio remnant of eleven separate manuscripts, nine of which are in Christian Palestinian Aramaic, which have been dated to the 5th or 6th century CE; and two of which are in Greek, which have been dated to the 7th or 8th century CE.

The Christian Palestinian Aramaic sections contain lectionary pericopes of the four Gospels and Epistles, as well as biblical manuscripts of the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles, remains of (lectionary) lessons of the Old Testament, and sections of the early Christian apocryphal Dormition of the Mother of God (Transitus Mariae) as well as one or two unknown homilies on 112 folios (23 by 18.5 cm), written in two columns per page, 18 to 23 lines per page in an adapted Syriac Estrangela square script.[4][5] This manuscript is the second largest early corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic after Codex Sinaiticus Rescriptus from Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai.[6]

The Greek section contains the text of the four Gospels, with numerous lacunae, on 34 parchment folios (23 by 15.5 cm). Written in two columns per page, 31 lines per page, in uncial letters. According to Ian A. Moir this manuscript contains a substantial record of an early Greek uncial manuscript of the Gospels once at Caesarea, which would have been the sister of Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus, but is now lost.[7][8] The Christian Palestinian Aramaic texts were read and edited by Agnes Smith Lewis and the Greek text by Ian A. Moir,[9][10] and many of the readings for the Christian Palestinian Aramaic part could be improved for the reeditions by Christa Müller-Kessler and Michael Sokoloff.[11] Two folios are attributed to the Dormition of the Mother of God and were reedited.[12] The missing eigthteenth quire can be added from the New Finds (1975) in Saint Catherine’s Monastery.[13][14]

Contents

In Christian Palestinian Aramaic:

- CCR 1

- a Gospel manuscript including texts of Matthew and Mark

Matt. 21:23-41; 27-31; 22:40-23:1; 23:1-25; 24:42-46; 24: 25:14; 26:24-32; 26:40-49; 27:9-19; 27:39-48; 27:64-28:3; 28:4-10

Mark 1:1-10; 1:20-30; 2:2-11; 17-24

- CCR 2A

- a Gospel of John in Christian Palestinian Aramaic, plus

the Acts and Epistles

Acts 19:31-36; 20:1; 20:2-7; 20:8-14; 21:3-8; 21:9-14; 24:25-25:1; 25:3-26; 26:23-29; 27:1-13; 27:14-27

- CCR 2B

Romans 4:17-22; 5:4-15; 6:14-19; 7:2-11; 8: 9-21; 9:30;10:3-9; 15:11-21

I Corin. 1:6-23; 2:10-3:5; 4:1-15; 5:7-6:5; 10:18-31; 12:12-24; 13:4-11; 14:4-7; 14:8-14; 14:14-24; 14:24-37; 15:3-10; 15:10-24; 15:24-49; 16:3-16; 16:16-24

II Corin. 1:1-3; 1:23-2:11; 2:11-3:5; 4:18-5:6; 5:6-12; 6:3-16; 7:3-8

Galat. 1:1-23; 3:20-24; 4:2; 4:4-29; 5:1; 5:24; 6:4-12; 6: 4

Eph. 1:18-2:8; 4:14-27; 5:8-16; 5:17-24

Phil. 2:12-26

Coloss. 4: 6-17

I Thess.1:3-9; 5:15-26

II Thess. 1:3-2:2

II Timothy 3:2-14

Titus 2:7-3:3

Philemon 11-25

1 John 1:1-9

II Peter 1:1-12; 3:16-18

- CCR 3

- a lectionary including portions of the Old Testament as well as the New Testament

Exodus 4:14-18

Deut. 6: 4-21; 7:1-26

I Sam. 1:1; 2:19-29; 4:1-6; 6:5-18

Job 6:1-26; 7: 4-21

Psalms 2:7; 40(41):1; 50(51):1; 56(57):1; 109(110):1; 131(132):1

Proverbs 1:20-22

Isaiah 40:1-8; 63:9-11

Jerem. 11:22-12: 4-8

Joel 2:12-14; 2:20

Micah 4:1-3; 4:3-5

Matt. 1:18-25; 2:1-2; 2:2-8; 2:18-23

Luke 1: 26-38

- CCR 7

- a biblical manuscript:

Leviticus 8:18-30; 11:42-12:2-8

- CCR 8

- a Gospel lectionary:

Matt. 27:27-41

Mark 15:16-19

John 13:15-29

John 15:19-26; 16:9

- CCR 4

Fragment of an unknown apocryphal homily about the life of Jesus;

Dormition of the Mother of God (Transitus Mariae) with chapters 121-122; 125–126 according to the Ethiopic transmission.[12]

- In Greek (CCR 5 & 6)

Matt. 2:12-23; 3:13-15; 5:1-2.4.30-37; 6:1-4.16-18; 7:12.15-20; 8:7.10-13.16-17.20-21; 9:27-31.36; 10:5; 12:36-38.43-45; 13:36-46; 26:75-27:2.11.13-16.18.20.22-23.26-40;

Mark 14:72-15:2.4-7.10-24.26-28;

Luke 22:60-62.66-67; 23:3-4.20-26.32-34.38;

John 6:53-7:25.45.48-51; 8:12-44; 9:12-10:15; 10:41-12:3.6.9.14-24.26-35.44-49; 14:22-15:15; 16:13-18; 16:29-17:5; 18:1-9.11-13.18-24.28-29.31; 18:36-19:1.4.6.9.16.18.23-24.31-34; 20:1-2.13-16.18-20.25; 20:28-21:1.[15]

Text

The Greek text of the codex 0250 is mixed with a predominant element of the Byzantine text-type. Aland placed it in Category III.[7]

Gregory classified it as lectionary (ℓ 1561).[16]

Matthew 8:12

- it has ἐξελεύσονται (will go out) instead of ἐκβληθήσονται (will be thrown). This variant is supported only by one Greek manuscript Codex Sinaiticus, by Latin Codex Bobiensis, syrc, s, p, pal, arm, and Diatessaron.[17]

Matthew 8:13

- It has additional text (see Luke 7:10): και υποστρεψας ο εκατονταρχος εις τον οικον αυτου εν αυτη τη ωρα ευρεν τον παιδα υγιαινοντα (and when the centurion returned to the house in that hour, he found the slave well) along with א, C, (N), Θ, f1, (33, 1241), g1, syrh.[18]

Matthew 27:35

Discovery and present location

One folio of the codex was purchased by Agnes Smith Lewis in Cairo in 1895, 89 folios were received from an undisclosed Berlin scholar in 1905, and 48 further ones were acquired in Port Tewfik in 1906.[9][10] One folio was bought by Alphonse Mingana.[19] This folio had been already in the hand of Agnes Smith Lewis in 1895.[9] Eight leaves (Sinai, Syriac NF 38) surfaced among the New Finds in Saint Catherine’s Monastery from 1975.[13]

Until 2010, the codex was housed at the Westminster College in Cambridge, formerly donated by Agnes S. Lewis and Margaret D. Gibson to this College. It was listed for sale at a Sotheby's auction, where it failed to sell on July 7, 2009.[20] In 2010, Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby and evangelical Christian, bought the codex directly from Sotheby's after their auction ended unsuccessfully. The codex now resides in the Green Collection.[21] but one folio is still kept in the Mingana Collection, Birmingham,[22] and eight more folios are stored from the New Finds (1975) in Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai.[23]

References

- Sebastian P. Brock, Ktabe mpassqe: Dismembered and Reconstructed Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic Manuscripts: Some Examples, Ancient and Modern, Hugoye 15, 2012, pp. 12–13.

- Sinai Palimpsest Project

- K. Aland, M. Welte, B. Köster, K. Junack, "Kurzgefasste Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neues Testaments", (Berlin, New York 1994), p. 40.

- Friedrich Schulthess, Grammatik des christlich-palästinischen Aramäischen (Tübingen, 1924), pp. 4–5.

- Christa Müller-Kessler, Grammatik des Christlich-Palästinisch-Aramäischen. Teil 1. Schriftlehre, Lautlehre, Formenlehre (Texte und Studien zur Orientalistik 6; Hildesheim, 1991), pp. 16, 28–29.

- Sinai Palimpsest Project

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Agnes Smith Lewis, Codex Climaci rescriptus, Horae Semiticae, VIII (Cambridge, 1909).

- Ian A. Moir, Codex Climaci rescriptus graecus (Ms. Gregory 1561, L), Texts and Studies NS, 2 (Cambridge, 1956).

- Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, vol. I–IIA/B

- Christa Müller-Kessler, An Overlooked Christian Palestinian Aramaic Witness of the Dormition of Mary in Codex Climaci Rescriptus (CCR IV), Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 16, 2019, pp. 81–98.

- Sebastian P. Brock, The Syriac New Finds at St. Catherines’s Monastery, Sinai, and Their Significance, The Harp 27, 2011, pp. 48–49.

- Sinai Palimpsest Project

- Kurt Aland, Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum. Locis parallelis evangeliorum apocryphorum et patrum adhibitis edidit, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1996, p. XXVI.

- C. R. Gregory, Textkritik des Neuen Testaments, Leipzig 1909, vol. 3, p. 1374-1375.

- UBS4, p. 26.

- NA26, p. 18

- Hugo Duensing, Zwei christlich-palästinisch-aramäische Fragmente aus der Apostelgeschichte, Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 37, 1938, pp. 42–46; Matthew Black, A Palestinian Syriac Leaf of Acts XXI, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 23, 1939, pp. 201–214.

- Sotheby's Auctions Forbes Magazine report.

- Candida R. Moss and Joel S. Baden, Bible Nation. The United States of Hobby Lobby. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019, p. 28–29 ISBN 978-0-691-19170-6

- Matthew Black, A Palestinian Syriac Leaf of Acts XXI, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 23, 1939, pp. 201–214.

- Sinai Palimpsest Project

Text editions

- Agnes Smith Lewis, Codex Climaci rescriptus, Horae Semiticae, VIII (Cambridge, 1909).

- Hugo Duensing, Zwei christlich-palästinisch-aramäische Fragmente aus der Apostelgeschichte, Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 37, 1938, pp. 42–46.

- Matthew Black, A Palestinian Syriac Leaf of Acts XXI, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 23, 1939, pp. 201–214.

- Ian A. Moir, Codex Climaci rescriptus grecus (Ms. Gregory 1561, L), Texts and Studies NS, 2 (Cambridge, 1956).

- Christa Müller-Kessler and M. Sokoloff, The Christian Palestinian Aramaic Old Testament and Apocrypha, Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, I (Groningen, 1997). ISBN 90-5693-007-9

- Christa Müller-Kessler and M. Sokoloff, The Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period. Gospels, Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, IIA (Groningen, 1998). ISBN 90-5693-018-4

- Christa Müller-Kessler and M. Sokoloff, The Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period. Acts of the Apostles and Epistles, Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic. IIB (Groningen, 1998). ISBN 90-5693-019-2

- Christa Müller-Kessler, An Overlooked Christian Palestinian Aramaic Witness of the Dormition of Mary in Codex Climaci Rescriptus (CCR IV), Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 16, 2019, pp. 81–98.

Further reading

- Agnes Smith Lewis, A Palestinian Syriac Lectionary containing Lessons from the Pentateuch, Job, Proverbs, Prophets, Acts and Epistles, Studia Sinaitica VI (London, 1895), p. cxxxix.

- Bruce M. Metzger, VI. The Palestinian Syriac Version.The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford, 1977), pp. 75–82.

- Christa Müller-Kessler, Christian Palestinian Aramaic and Its Significance to the Western Aramaic Dialect Group, Journal of the American Oriental Society 119, 1999, pp. 631–636.

- Christa Müller-Kessler, Die Frühe Christlich-Palästinisch-Aramäische Evangelienhandschrift CCR1 übersetzt durch einen Ostaramäischen (Syrischen) Schreiber?, Journal for the Aramaic Bible 1, 1999, pp. 79–86.

- Alain Desreumaux, L’apport des palimpsestes araméens christo-palestiniens: le case du Codex Zosimi Rescriptus et du Codex Climaci rescriptus’, in V. Somers (ed.), Palimpsestes et éditions de textes: les textes littéraires, Publications de l’Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, 56 (Louvain, 2009), pp. 201-211.

- Sebastian P. Brock, The Syriac ‘New Finds’ at St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai and Their Significance, The Harp 27, 2011, pp. 39–52.

- Sebastian P. Brock, Ktabe mpassqe: Dismembered and Reconstructed Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic Manuscripts: Some Examples, Ancient and Modern, Hugoye 15, 2012, pp. 7–20.

External links

- Uncial 0250 at the Wieland Willker, "Textual Commentary"

- Sinai Palimpsest Project at the Monastery of Saint Catherine