Comparison of American and Canadian football

American and Canadian football are gridiron codes of football that are very similar; both have their origins in rugby football, but some key differences exist.

.jpg.webp)

History

Rugby football was introduced to North America in Canada by the British Army garrison in Montreal, which played a series of games with McGill University.[1] In 1874, the United States' Harvard University hosted Canada's McGill University to play the new game derived from rugby football in a home-and-home series.

When the Canadians arrived several days early, to take advantage of the trip to see Boston and the surrounding areas, they held daily practices. During this time, the Americans were surprised to see the Canadians kick, chase, and then run with the ball. Picking up and running with the ball violated a basic rule of the American game of the day; when the U.S. captain (Henry Grant) pointed this out to the captain of the Canadian team (David Roger), the reply was simple: Running with the ball is a core part of the Canadian game. When the American asked which game the Canadians played, David replied "rugby". After some negotiation, they decided to play a game with half and half Canadian/U.S. rules. Thus, many of the similarities and differences between the Canadian and American games indeed came out of this original series where each home team set the rules. For instance, Harvard, because of a lack of campus space, did not have a full-sized rugby pitch. Their pitch was only 100 yd (91 m) long by 50 yd (46 m) wide with undersized end zones (slightly less than the 53⅓-yard width of the current regulation-sized field for American football).

Because of the reduced field, the Harvard team opted for 11 players per side, four fewer than the regulation 15 of rugby union. To generate more offense, Harvard also increased the number of downs from three, as set by McGill, to four. Furthermore, the Harvard players so enjoyed running with the ball, this rule was wholly adopted into all Harvard play following the two games with McGill. While the American team bested the Canadian (3–0 and a following tie game), both countries' flavours of football were forever changed and linked to one another. Both the Canadian and American games still have some things in common with the two varieties of rugby, especially rugby league, and because of the similarities, the National Football League (NFL) had a formal relationship with the Canadian Football League (CFL) between 1997 and 2008.[2]

Many, if perhaps not most, of the rules differences have arisen because of rules changes in American football in the early 20th century, which have not been copied by Canadian football. The major Canadian codes never abolished the onside scrimmage kick (see Kicker advancing the ball below) or restricted backfield motion, while the American college football (from whose code all American codes derive) did. Canadian football was later in adopting the hand snap and the forward pass, although one would not suspect the latter from play today. Additionally, Canadian football was slower in removing restrictions on blocking, but caught up by the 1970s so that no significant differences remain today. Similarly, differences in scoring (the Canadian game valuing touchdowns less) opened up from the late 19th century, but were erased by the 1950s. An area in which American football has been more conservative is the retention of the fair catch (see below). The American game's modern rules were developed by Walter Camp in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whereas the modern Canadian game was devised by John Thrift Meldrum Burnside, whose Burnside rules, invented around the same time, were developed independently from Camp's rules.

In some regions along the Canada-U.S. border, especially western areas, some high schools from opposite sides of the border regularly play games against one another (typically one or two per team per season). By agreement between the governing bodies involved, the field of the home team is considered a legal field, although it is a different size from one school's normal field. In all but a few cases, the rules of the home team are followed throughout the game.

Many CFL players are Americans who grew up playing American football and cannot find a place in the NFL, or who prefer to play in the CFL; strict import quotas restrict the number of non-Canadian players. Furthermore, the classifications of import (non-Canadian) and non-import (Canadian) were highly restrictive and required a player to have been in Canada since childhood to qualify as a nonimport (i.e. a player cannot simply become a Canadian citizen and become a nonimport, nor can he arrive in Canada during high school or college; both scenarios would still have the player in question classified as an import and counted against the team's maximum); these restrictions were loosened beginning in 2014 so that anyone who had become a Canadian citizen at any time before signing with the league for the first time could qualify as a nonimport player. For individuals who played both American and Canadian football professionally, their career statistic totals are considered to be their combined totals from their careers in both the CFL and NFL. Warren Moon, for example, was the all-time professional football leader in passing yards after an illustrious career in both leagues. He was surpassed in 2006 by Damon Allen, who in turn was surpassed by Anthony Calvillo in 2011, both of whose careers were exclusively in the CFL.

Differences

Several important specific differences exist between the Canadian and American versions of the game of football:

Playing area

The official playing field in Canadian football is larger than the American, and similar to American fields prior to 1912. The Canadian field of play is 110 by 65 yards (100.6 by 59.44 m), rather than 100 by 53 1⁄3 yards (91.44 by 48.77 m) as in American football. Since 1986, Canadian end zones are 10 yards deeper than American football, measuring 20 yards (18.29 m).

The end zones were previously 25 yards, with Vancouver's BC Place the first to use the 20-yard-long end zone in 1983, and since 2016, the home of the CFL's Toronto Argonauts, BMO Field, uses an 18-yard-long end zone.[3] Including the end zones, the American field is about 34% smaller than the Canadian field (87,750 square feet (8,152 m2) for the Canadian field vs 57,600 square feet (5,350 m2) for the American field), but the Canadian field occasionally will have its end zone truncated at the corners so that the field fits in the infield of a running track. The only example in the CFL is the Percival Molson Memorial Stadium, home of the Montreal Alouettes.

The goalposts for kicking are placed at the goal line in Canadian football, but at the end line in the American game since 1974. In Canadian rules, the distance between the sideline and hash marks is 24 yards (21.9 m); in American amateur rules, at the high school level, the distance is 17 yards 2 feet 4 inches (16.26 m), virtually sectioning the field into three equal columns. The hash marks are closer together at the American college level, where they are 20 yards (18.29 m) from the sideline, and in the NFL, where they are 23 yd 1 ft 9 in (21.56 m) from the sideline and the distance between them is the same as that between the goalposts.[4]

Because of the larger field, many American football venues are generally unfit for the Canadian game. While several American stadia could accommodate the extra 17 1⁄2 feet ( 5 5⁄6 yards (5.33 m) per side in width (multipurpose stadia, baseball parks converted for football, and some soccer-specific stadiums are particularly good fits), most American stadia would lose between 15 and 18 rows of seating in each end zone because the field is 15 yards (13.72 m) longer on each end. In many smaller venues, this would be the entire end zone section, losing seating for at least 3,000 spectators.

During the CFL's failed expansion to U.S. cities in the early 1990s, Canadian football was either played on fields designed to accommodate both American football and baseball (such as the Baltimore Stallions playing at Memorial Stadium), or in some cases, on a field designed for American football (for instance, the Memphis Mad Dogs and the Birmingham Barracudas of the CFL, playing in the Liberty Bowl and at Legion Field, respectively, played the Canadian game on modified American-sized fields because of the inability of the stadia to adapt to the larger field). The Alamodome, originally built as a multipurpose dome, proved to best accommodate both Canadian football (the CFL's San Antonio Texans) and American football (Alamo Bowl, Dallas Cowboys training camp, the New Orleans Saints after Hurricane Katrina, the NFLPA Game, the U.S. Army All-American Bowl, and the UTSA Roadrunners), although Canadian football is no longer played there. Similarly, Hornet Stadium fairly easily adapted to both the Canadian and American games, as it was built with a running track in which the Canadian field fits with only some cuts to the corners. Hornet Stadium hosts California State University, Sacramento (more often known as Sacramento State), hosted the Sacramento Surge and Sacramento Mountain Lions in American football and the Sacramento Gold Miners in Canadian football.

Team size

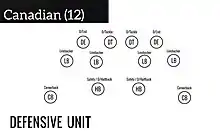

American teams use 11 players, while Canadian teams have 12 players on the field per side. Both games have the same number of offensive players required at the line of scrimmage, so the 12th player in the Canadian game plays a backfield position on offence, whereas this is usually a defensive back on defence.[5]

Because of this, position designations of the various offensive and defensive lines vary. For example, most formations in Canadian football have no tight ends, these having been phased out in 1980.[6] The typical offensive arrangement in Canadian football is two slotbacks instead of the American tight end, while on the defensive end of the ball, two defensive halfbacks are used instead of one strong safety in the American game.

The ball

_(6932187715).jpg.webp)

The sizes of individual American and Canadian footballs can vary within specified size limitations. Despite the CFL and NFL having different specifications until 2018, they overlapped to a sufficient degree that from at least 1985 forward, the same ball could fall within the requirements of both leagues.

Historically the CFL ball was slightly larger, both because of slightly bigger specifications, but also because CFL manufacturers tended to make balls at the larger end of the allowed tolerances as opposed to NFL manufacturers, which built balls to the smaller end. However, the CFL has updated its specifications twice—first in 1985,[7] and most recently in 2018. The latter change saw the league adopt the NFL's specifications.[8]

Before it adopted NFL standards, the CFL's regulation football size was specified as short circumference from 20 7⁄8 to 21 1⁄8 inches (530 to 537 mm); long circumference from 27 3⁄4 to 28 1⁄4 inches (705 to 718 mm).[9]

The regulation size for an NFL football is specified as short circumference from 21 to 21 1⁄4 inches (533 to 540 mm); long circumference from 28 to 28 1⁄2 inches (711 to 724 mm).[10]

Despite the fact that before 2018, the CFL rules allowed for a smaller legal ball and the NFL rules allowed for a larger legal ball, a common misconception existed among media, fans, and even players that the then-current CFL ball was bigger. Some professional quarterbacks stated that they noticed a difference in size.[11]

Another difference between NFL and CFL balls is that Canadian balls have two 1-inch (25 mm) complete white stripes around the football 3 in (76 mm) from the largest diameter of the ball and NFL balls have no stripes at all. The CFL retained its striping scheme when it adopted NFL measurement specifications in 2018.[8] College football and high school football both specify the use of stripes, but only on two of the football's four panels (the ones adjacent to the laces).

Number of downs

In American football, a team has four downs to advance the ball 10 yards, while in Canadian football the limit is three downs.[12][13]

Scrimmage

In both games, the ball is placed at a line of scrimmage, in which a player known as the "centre" or "center" performs a "snap" to start a football play. In Canadian football, the snap is required to go between the centre's legs; no such move is required in American football, but it is invariably done this way anyway, so the center is in position to block following the snap. The defensive team must stay a set distance away from the line of scrimmage on their side of the line.

In Canadian football, the distance between the line of scrimmage and the defensive team, formally called the "scrimmage zone", is one full yard.[14] Because of this one-yard distance, teams tend to gamble on "third and one" or "third and inches". If a team's offense is within one yard of either goal line, the line of scrimmage is moved to the one-yard line.[15]

In American football, the set distance between the offensive and defensive teams, known in that code as the "neutral zone", is 11 inches – the length of the ball, creating the illusion of the teams being "nose-to-nose" against each other.

While large, relatively immobile offensive line players used to form a line that cannot be easily penetrated by the defense are valued in American football, the extra distance from the defensive team means Canadian football finds value in more nimble players on the offensive line.[16]

Fair catches and punt returns

In American football, if a punt returner sees that, in his judgment, he will be unable to advance the ball after catching it, he may signal for a fair catch by waving his hand in the air, and forgo the attempt to advance. If he makes this signal, the opposing team must allow him to attempt to catch the ball cleanly; if he is interfered with, the team covering the kick will be penalized 15 yards. In contrast, Canadian football has no such rule; instead, no player from the kicking team, except the kicker or any player who was behind him when he kicked the ball, may approach within five yards of the ball until it has been touched by an opponent. If they do, a "no yards" penalty is called against the kicking team. Penalties for "no yards" calls vary on whether the ball made contact with the ground or not. The penalty is 5 yards if the ball has bounced and 15 if the ball is caught in the air.[17]

Furthermore, in American football, the receiving team may elect not to play the ball if the prospects for a return are not good and the returner is not certain he can successfully catch the ball on the fly; American players are generally taught not to attempt to touch a bouncing football. If any member of the kicking team touches the ball after the kick is made, without an intervening touch by the member of the receiving team, the receiving team may elect to scrimmage the ball from that spot of first touching, regardless of anything else (other than a penalty) that happens during the rest of the play. If the kicking team gains possession of the ball during the kick before it is touched by the receiving team, the ball is then dead. Often, the ball hits the ground and is surrounded by players from the kicking team, who allow it to roll as far as possible downfield – without going into the end zone – before grasping or holding the ball against the ground. (If a punt bounces into the receiving team's end zone, it is dead, and a touchback is awarded.) However, if the ball touches a member of the receiving team without his gaining possession (a "muff"), then the ball can be recovered by either team (but cannot be advanced by the kicking team). If the kicking team recovers the ball, they regain possession and are awarded a first down at the spot of the recovery.

Following a fair catch in American football, the receiving team can elect a free kick (called a fair catch kick) from the spot the ball is received – and if the kick goes through the opposite goal posts, a field goal is scored. Fair catch kicks are rarely attempted in the NFL and are usually unsuccessful (The last successful fair catch kick was in 1976). The fair catch kick is not allowed in college football.

In Canadian football, if the receiving team does not play the ball, the kicker, and any teammates behind the kicker at the time of the kick, can attempt to retrieve and advance the ball. This is further explained in the kicker advancing the ball section.

Motion at the snap

In American football, after all players are set, only one offensive player is allowed to be in motion, and he cannot be moving toward the line of scrimmage while the ball is snapped. The motion player must start from behind the line of scrimmage; players on the line cannot be in motion.[18]

In Canadian football, all offensive backfield players, except the quarterback, may be in motion at the snap; players in motion may move in any direction as long as they are behind the line of scrimmage at the snap. In addition, the two players on the ends of the line of scrimmage (generally wide receivers) may also be in motion along the line.[15] Many teams encourage this unlimited motion, as it can confuse the defence. It also provides receivers the advantage of a running start, as they can time their runs so that they cross the line of scrimmage at speed when the ball is snapped, allowing them to get downfield faster than receivers in American football, allowing for comparatively longer throws in the same amount of time after the snap or quicker throws for a given distance.

Time rules

In American football, the offensive team must run a play within 25 seconds of the referee whistling the play in – except in the NCAA (college) and the NFL where teams have 40 seconds from the end of the previous play, or 25 seconds following a penalty or timeout. In Canadian football (at all levels of play), teams have 20 seconds regardless of the preceding situation.[19]

American football rules allow each team to have three timeouts in each half, and the NFL stops play for a "two-minute warning". However, NCAA football has no two-minute warning, but the clock stops on a first down until the ball is ready for play if the play ended in the field of play. In the CFL, each team has two time-outs a game, but cannot use both in the last three minutes of the game, while at lower levels of Canadian football, each team has two. Canadian football has a three-minute rather than a two-minute warning. Also, at all levels of Canadian football, the clock is stopped after every play during the last three minutes of each half. Once the referee has set the ball, the clock restarts if the last play ended with a runner tackled in the field of play.

Timing rules change drastically after the minutes warning in both leagues:

- In American football, the clock continues to run after any tackle in bounds, but stops after an incomplete pass or a tackle out of bounds. If the clock stops, it is restarted at the snap of the ball or when the ball is ready to be played. In Canadian football, the clock stops after every play, but the starting time differs depending on the result of the previous play: After a tackle in bounds, the clock restarts when the referee whistles the ball in; after an incomplete pass or a tackle out of bounds, the clock restarts when the ball is snapped. In the NCAA, the clock stops after every first down to move and set the down markers, after which the clock restarts.

- The penalty for allowing the play clock to run out, which is 5 yards with no loss of down before the minutes warning in both codes, dramatically diverges after that point. In American football, the penalty for "delay of game" remains 5 yards with the down repeated. In Canadian football, the penalty for a "time count" violation ("delay of game" is a different violation in Canada) is loss of down on first or second down, and 10 yards with the down repeated on third down. Also, if the referee deems a time count violation on third down after the three-minute warning to be deliberate, he has the right to require the offensive team to legally put the ball into play within the 20-second count, with a violation resulting in loss of possession. (Note that the enforcement of time count during convert attempts does not change at the warning; it is 5 yards with the down repeated throughout the game.)[20]

- In American football, a period generally ends when time expires (though any play which is in progress when the clock reaches 0:00 is allowed to finish); in Canadian football, the period must end with a final play. Consequently, a play is often started in Canadian football with no time (0:00) showing on the game clock. American football typically only has a play start with no time on the clock when a defensive penalty occurs during the last play of the period and the penalty is not declined (or, in the NFL, in the very rare circumstance when a team takes a fair catch as time expires and elects a free kick). Additionally, any period in Canadian football cannot end on a penalty (this is not the case in American football), so any penalty that occurs with 0:00 left in Canada extends the period by at least one more play.

These timing differences, combined with the fewer downs available for the Canadian offence to earn a first down, lead to spectacularly different end games if the team leading the game has the ball. In American football, if the other team is out of timeouts, running slightly more than 120 seconds (two minutes) off the clock without gaining a first down is possible. In Canadian football, just over 40 seconds can be run off.

Kicker advancing the ball

Canadian football retains much more liberal rules regarding recovery of the ball by members of the kicking team. On any kick, the kicker and any member of the kicker's team behind the kicker at the time of the kick may recover and advance the ball. On a kickoff, since every member of the kicking team must be behind the ball when it is kicked, this effectively makes all 12 players "onside" and eligible to recover the kick, once it has gone 10 yards downfield. On a punt or missed field goal, usually only the kicker is onside, as no one is behind the kicker. All of the players offside at the time of the kick may neither touch the ball nor be within 5 yards of the member of the receiving team who fields the kick; violation of this rule is a penalty for "no yards". The penalty for no yards is 15 yards if the kick is in flight and 5 yards if it has been grounded.

The American rules are similar for the recovery of kickoffs. Any member of the kicking team may recover the ball once it has touched an opponent or once it has gone 10 yards downfield and touched the ground. The ball is dead when recovered, though the kicking team is awarded possession at the spot of recovery.

The American rules differ from the Canadian ones for scrimmage kicks. In American rules, to recover a scrimmage kick (punt or missed field goal) and retain possession, the ball must be touched beyond the line of scrimmage by a member of the receiving team (defense). If the ball is touched by the receiving team and then recovered by the kicking team, the kicking team retains possession and is awarded a first down. If the receiving team has not touched the ball before the kicking team touches it, it is "first touching" as described above in fair catches and punt returns.

Additionally, members of the kicking team must allow the receiving team the opportunity to catch a scrimmage kick in flight. No distance is required; the NCAA revoked its rule of a 2-yard halo.[21] Once the scrimmage kick has touched the ground, the kicking team is free to recover, subject to the first touching rules.

In both codes, a scrimmage kick that is blocked and recovered by the kicking team behind the line of scrimmage is in play. The kicking team may then choose to either attempt another kick or try to advance the ball, but no turnover has taken place on the play (unless a member of the receiving team has control of the ball), and therefore, the kicking team either has to advance the ball to the first-down marker, or loses the down, which often results in a turnover on downs.

Blocking receivers

Under Canadian rules, the defensive line can only hold up or block a receiver within one yard of the scrimmage lines. In the NFL, contact up to 5 yards from the line is allowed. This allows for more open plays in Canadian football.

Fumbles out of bounds

In Canadian play, if the ball is fumbled out of bounds, the play ends with possession going to the team to last contact the ball in bounds (after the ball has completely left the possession of the fumbling ball carrier). A loose ball may be kicked forward (dribbled) provided it is then recovered by a player who is onside at the time of said kick. The ball may not, however, be intentionally kicked out of bounds to gain possession, this is then treated as a scrimmage kick out of bounds and possession goes to the opposing team. Incidental contact with the foot does not count as kicking the ball out of bounds. In American play, when a ball is fumbled out of bounds, the last team to have clear possession of the football is awarded possession, unless the ball goes out of the back or side of the end zone.

A team may still lose possession after a fumble out of bounds if the fumble occurred on fourth down (third down in Canadian play) and the ball becomes dead short of the line to gain. Because of plays like the Holy Roller, the NFL changed its rule regarding advancing a fumbled ball on offense. If the offensive team fumbles in the last two minutes of either half, or on fourth down at any time, only the player who fumbled is allowed to advance the ball past the point of the fumble. If any other offensive player advances the ball toward the opponent's goal line, the ball is moved back to the spot of the fumble. If the fumble occurred on fourth down, the defensive team gains possession on downs unless the original fumble occurred after the line to gain had been reached.

Field goals, singles, and touchbacks

In Canadian football, any kick that goes into the end zone is a live ball, except for a successful field goal or if the goalposts are hit while the ball is in flight. If the player receiving the kick fails to return it out of the end zone, or (except on a kickoff) if the ball was kicked through the end zone, then the kicking team scores a single point (rouge), and the returning team scrimmages from its 35-yard line or, if the rouge is scored as a result of a missed field goal attempt, the receiving team may choose the last point of scrimmage. If a kickoff goes through the end zone without a player touching it or a kicked ball in flight hits a post without scoring a field goal, there is no score, and the receiving team scrimmages from its 25-yard line. If the kick is returned out of the end zone, the receiving team next scrimmages from the place that was reached (or if they reach the opponents' goal line, they score a touchdown); in the amateur levels of the game, they are given the ball at their 20-yard line if the kick was not returned that far.[22]

Singles do not exist in American football; however, only one point is counted when a safety is scored during a conversion attempt, in contrast to the two points scored on other safeties.

American football also allows a defending team to advance a missed field goal; however, because of the absence of singles and the goalpost position at the back of the end zone, the return is rarely exercised, except on a blocked kick, or as time expires in the half or in the game (with the most famous recent example being Chris Davis' game-ending return of a missed field goal for the winning touchdown in the 2013 Alabama–Auburn game). Most teams instead elect not to attempt a return and assume possession – at the previous line of scrimmage in the NCAA and at the spot of the kick in the NFL. Since the goalpost is out of bounds, any nonscoring kick that strikes the goalpost is dead, and the receiving team takes over possession from the spot of the kick or their own 20-yard line, whichever is further from the receiving team's goal. Likewise, any kickoff or punt that either is kicked through the end zone, is kicked into the end zone and rolls out of bounds (without being touched by a player), is touched in the end zone by a member of the kicking team (with no member of the receiving team having touched it), or is downed in the end zone by a member of the receiving team, results in a touchback. The placement of the ball after a touchback varies by rule set and game situation. Under high school rules, the receiving team is awarded possession on its own 20-yard line in all situations. In the NCAA and NFL, the ball is moved to the 20-yard line following a punt, and to the 25-yard line following a kickoff, or free kick after a safety. Under NCAA rules (but not those of the NFL), a kickoff or free kick after a safety that ends in a fair catch by the receiving team inside its own 25-yard line is treated as a touchback, with the ball moved to the 25. If a player of the receiving team fields a kickoff or punt in the end zone, he has the option to down it in the end zone (resulting in a touchback) or to try to advance the ball.

Following a successful field goal, in Canadian rules, the team scored upon has the option of receiving a kickoff, kicking off from its 35-yard line, or scrimmaging at its own 35-yard line (the CFL first instituted this rule in 1975, but eliminated this last option for the 2009 season, but it was reinstated for 2010). In American football, a kickoff is performed by the scoring team after every score, with the exception of safeties. The option for the scored-upon team to kick off after a touchdown exists in American amateur football, but it is very rarely exercised.

Open-field kick

Canadian football retains the open-field kick as a legal play, allowing a kick to be taken from anywhere on the field. The open-field kick may be used as a desperation last play by the offense; realizing they are unable to go the length of the field, they advance part of the way and attempt a drop kick, trying to score a field goal, or recover the ball in the end zone for a touchdown.[23] Like a punt or missed field goal, the team receiving the kick is allowed a 5-yard buffer to recover the kick.

Conversely, the defence, facing a last-second field goal attempt in a tie game or game they lead by one point, often positions its punter and place-kicker in the end zone. If the field goal is missed, they can punt the ball back into the field of play and not concede a single. Multiple such kicks may be attempted on the same play. During the October 29, 2010, Toronto Argonauts game against the Montreal Alouettes, four kicks occurred in one play; after a Montreal missed field goal, the Argonauts punted from the end zone to about the 20-yard line. The ball was caught and immediately punted back to the end zone by Montreal to attempt a single, and finally the Argos punted, but failed to kick it out of the end zone, where the Alouettes recovered it for a touchdown.[24] [25]

American football only allows free kicks and scrimmage kicks made from behind the line of scrimmage; any kick beyond the line of scrimmage or after change of possession would result in a penalty. (Some levels of American football allow the rare fair catch kick, which according to the NFL rules is neither a free kick nor scrimmage kick, but sui generis.)

Safeties

In both American and Canadian football, a safety (or safety touch) awards two points to the defending team if the offensive team is brought down in their end zone. In American football, the team giving up the safety must take a "free kick" from their own 20-yard line. In Canadian football, the team being awarded the two points has the option of scrimmaging from their own 35-yard line, kicking the ball off from their own 35-yard line, or having the opposing team kick off the ball from their own 35-yard line. In 2009, the CFL changed the last option to be a kick-off from their own 25-yard line.[26]

Points after touchdown

In both games, after a touchdown is scored, the scoring team may then attempt one play for additional points. In Canadian football, this play is called a "convert", and in American football, it is formally called a try or attempt, although it is more commonly referred to as either a conversion, extra point, or point after touchdown (PAT). The additional points may be earned through a kick or a play from scrimmage. If done via kick, the scoring team gains one point, and if done from a scrimmage, the scoring team gains two.

However, the position of the ball for attempts is different in the two games. Point-after-touchdown attempts are snapped from the following points (as of the 2015 season):.

- NFL: 15-yard line for placekick attempts (for a 33-yard attempt), 2-yard line for two-point conversion attempts

- Amateur American football (all levels): 3-yard line for all attempts

- CFL: 25-yard line for placekick attempts (for a 32-yard attempt), 3-yard line for two-point conversion attempts

- Amateur Canadian football (all levels): 5-yard line for all attempts

Because the goalposts are on the goal line in Canada and the end line in the United States, a CFL kicker is at the same distance from the goalposts as an NFL kicker. Before the 2015 CFL season, that league used the 5-yard line for all attempts (for a 12-yard attempt), which meant that the Canadian kicker was closer to the goalposts than an American kicker at any level. Amateur Canadian kickers remain closer to their goalposts than their American counterparts. Also prior to 2015, the NFL's line of scrimmage for extra points was the 2-yard line (for a 20-yard attempt).

According to the rules of both the NFL and NCAA, on conversion attempts, the ball is automatically spotted in the middle of the field at the appropriate scrimmage line unless a member of the kicking team expressly asks a referee for an alternative placement. Per the rules, the ball can be placed at another spot between the hash marks (especially for strategic positioning on a two-point conversion attempt) or at another spot further back from the 2-, 3-, or 15-yard line (not uncommon at lower levels of football, since as the season progresses, conditions may worsen toward the center of the field, especially at the spot from which the PAT is usually kicked; the kicker may thus request a spot where the footing is surer).

During conversions, the ball is considered live in the CFL, American collegiate football, Texas high schools, the now-defunct NFL Europa, and starting with the 2015 season the NFL itself. As such, this allows the defensive team to gain two points on an interception or fumble return should they reach the kicking team's end zone, or (in the CFL) one point should the defensive team make an open-field drop kick through the kicking team's goalposts. Conversely, in other levels of American football and amateur Canadian football, defensive teams cannot score during a try.

The use of small, rubberized "tees" for field goal/extra point converts (not the same as the kickoff tee; such "tees" use 1" or 2" varieties) varies depending on the level of play. Unlike in the lower ranks of football up to the college level (in both the American and Canadian game), the NFL has never allowed the use of the "tees" for field goal attempts, having always required kickers to kick off the ground for such attempts;[27] In 1948, the NCAA authorized the use of a small rubberized kicking tee for field goals and extra points, but banned them by 1989, requiring all such kicks from off the ground.[28][29] The Canadian Football League, despite its status as a professional league, does allow for the use of such a tee for field goals and convert kicks, but it is optional, as kickers can also kick off the ground if they so desire.[30]

Runner down

In Canadian amateur football, the ball is not dead if a player kneels momentarily to, and does, recover a rolling snap, onside/lateral pass, or opponent's kick, while in American amateur football, such a situation produces a dead ball, unless the player is the holder for a place kick. The holder is allowed to catch the snap or recover a rolling snap while on a knee to hold the kick and may also rise to catch a high snap and immediately return to a knee.

At professional levels in both games, unless it is a clearly willful kneel or slide by a ball carrier to go down, a player must be touched while on the ground, otherwise, the player may stand up and continue to advance the ball. Hitting a player who is kneeling, sliding, or clearly intends to run the ball out of bounds (especially quarterbacks) is generally viewed as unsportsmanlike and is often penalized, and in the most blatant of cases (especially if it happens in the dying seconds of a game), the player may be subject to off-field disciplinary action by their respective league governing body, usually in the form of fines or suspensions.

Overtime

The procedures to settle games that are tied at the end of regulation vary considerably among football leagues.

Most leagues other than the NFL, including the CFL, use a procedure frequently called the "Kansas Playoff", so named because it was first developed for high school-football in that state. The rules are summarized here:

- A coin toss at the start of overtime determines the team that first receives possession in overtime, and which end zone will be used.

- Each team in turn receives one possession starting with first-and-10 at a fixed point on the field, which varies according to league:

- US college: Opponent's 25-yard line for the first four overtime procedures.

- Each procedure after the fourth consists of a single scrimmage play from the opponent's 3-yard line, with kicks banned. Successful plays in this situation are scored as two-point conversions.[31]

- US high school (also British Columbia, where high schools play under American rules): Standard rules call for the opponent's 10-yard line, but state/provincial associations are free to use different yardage. The short-lived Alliance of American Football also used the opponent's 10-yard line.

- CFL: Opponent's 35-yard line

- US college: Opponent's 25-yard line for the first four overtime procedures.

- The game clock does not run, but the play clock is enforced.

- At all levels, possessions end when the offensive team scores, misses a field goal, or turns the ball over. Touchdowns are followed by a conversion attempt, with the following additional caveats:

- US college: Teams must attempt a two-point conversion starting with the third overtime procedure. Starting with the fifth overtime procedure, all plays are two-point conversion attempts, and scored as such.[31]

- CFL and AAF: A convert kick is not allowed in overtime—all conversion attempts must be scrimmage plays (i.e., two-point attempts).

- US and BC high school: Standard rules call for no restrictions on the type of conversion attempt, but some state/provincial associations may limit the use of kick tries.

- Ability of defensive team to score after gaining possession on a turnover:

- US college, CFL, AAF, Texas high school: Can advance the ball upon gaining possession; if it scores a touchdown, it will satisfy the condition of each team having a chance to score and thus end the game.

- US and BC high school (except Texas): Possession ends immediately.

- Each team receives one charged timeout per overtime procedure except in the CFL and AAF, which allow(ed) no timeouts in overtime.

- If the score remains tied at the end of an overtime procedure, another procedure follows (except as noted below), with the team that had the second possession in the previous procedure having the first possession of the next procedure.

- Limit on number of overtime procedures:

- US college and high school: No limit; procedures continue until a winner is decided.

- CFL: In regular season games, maximum of two procedures, with the game declared a tie if it remains level. In postseason games, procedures continue until a winner is decided.

- AAF: Same as CFL, except that only one procedure was allowed in regular-season games. The league folded without holding any playoff games.

One aspect of the AAF overtime rules was unique to that league—field goals were prohibited during overtime.

The NFL overtime is a modified sudden-death period of 15 minutes, for playoff games only; since the 2017 season, overtime periods in the preseason and regular season are 10 minutes, as part of an overall effort by the NFL to speed up games and reduce their length. If the team that receives the opening kickoff scores a touchdown, or the defensive team scores a safety, the game ends at that point. If the receiving team scores a field goal, the game continues with the scoring team kicking off, and the scored-upon team having a chance at possession. If that team scores a touchdown, or loses possession, the game ends; if it scores a field goal, overtime continues, with the next score by either team ending the game. In the regular season, if a game remains tied after the 10-minute period, it is declared a tie. In postseason games, there are multiple 15-minute periods until a winner is decided.

The overtime protocol of the second XFL, now also defunct, was significantly different from that of other leagues, being most similar to that used in US college football after that rule set's fourth overtime procedure:[32][33]

- Overtime consisted of a five-round "shootout" of two-point conversion attempts.

- No coin toss was used to determine the first possession—the visiting team started all rounds on offense.

- The defense could not score on a conversion attempt.

- The first defensive penalty against a team during a round resulted in the ball being moved to the 1-yard line. A second defensive penalty in that round resulted in a score being awarded to the offensive team.

- Pre-snap offensive penalties were enforced according to regular rules. Post-snap offensive penalties ended that side's offensive round, with no score.

- All five rounds were played unless one team attained an insurmountable lead. If the game was still tied after five rounds, extra rounds were played until the tie was broken.

Other differences

In American high school and college football, as well as at all levels of Canadian football, receivers need only have one foot in bounds (provided the player's other foot does not come down out of bounds until the catch is made) for a catch to count as a reception. NFL play requires receivers to get both feet on the ground and in bounds after making the catch for a reception to count. Up through the 2007 season, an NFL official could award a catch if it was judged that the receiver would have come down in bounds if he had not been pushed by a defender. This rule was based on a judgment call by the official, and was criticized for being inconsistent. The rule was dropped prior to the 2008 season by the NFL.[34]

- In Canadian football, defensive pass interference may be called on any legal forward pass, even when the receiver is behind the line of scrimmage. Pass interference rules in all levels of American football do not apply until the thrown ball crosses the neutral zone.

- Until 2010, when a forward pass was deemed to be "uncatchable", defensive interference with the intended receiver was penalized in Canadian football. This rule was dropped for 2010, bringing it in line with long-standing practice in American college and professional football.

CFL roster sizes are 46 players (rather than 53 as in the NFL, though only 45 will dress for a game). A CFL team may dress up to 44 players, composed of 21 "nationals" (essentially, Canadians), 20 "internationals" (almost exclusively Americans), and 3 quarterbacks.[35]

The traditional NFL football season runs from the 2nd week of September until late December or the start of January, with the NFL playoffs occurring in January and February. In contrast, the CFL regular season runs from late June to late October. This is in order to ensure the Grey Cup playoffs can be completed in mid-November, before the harsh Canadian winters set in. This is an important consideration for a sport played in outdoor venues in locations such as Regina, Edmonton and Winnipeg.

Officials' penalty flags used in the CFL are orange in color. In American football, officials typically use yellow penalty flags. Conversely, coaches' challenge flags for replays are yellow in the CFL as opposed to red in the NFL. In American leagues, the referee wears a solid white cap, and the other officials wear black with white piping.[35] Until 2018 in the CFL, the referee wore a black cap with white piping, and the other officials wore white caps with black piping; starting with the 2019 season, the referee now wears a white cap with black piping, and the other officials wear black ones with white piping, almost mirroring the American convention (and matching the standard for the lower levels of the game in Canada). Additionally, when announcing penalties, in American football, the penalized team is announced using generic terms ("offense"/"defense", for example), but in Canadian football (especially the CFL) the penalized team is announced by their respective city or province.

The CFL regular season comprises 18 games since 1986, while the NFL regular season has consisted of 16 games since 1978. There are several radical differences concerning how the leagues calculate regular season records and how ties in the standings are broken:

- The CFL awards two points for a win, one point for a tie and zero points for a loss (from 2000 to 2002 inclusive, the CFL also awarded one point for an overtime loss). The CFL ranking system is in keeping with the traditional system in most other football codes of British origin, and is also the basis for the system used in hockey. The NFL by contrast officially ranks its teams strictly by winning percentage, with ties counting as a "half-win" for the purposes of calculating winning percentage. Prior to 1972, ties were ignored altogether for the purposes of calculating NFL winning percentages, which actually made them more valuable than a "half-win": teams with a winning record including ties had an advantage in terms of earning a better winning percentage for the purposes of playoff qualification and teams with a losing record including ties had an advantage in terms of earning better draft position. In all competitions in both countries, it is popular for team records to be expressed in a simple "W-L" format, or in a "W-L-T" format if (and only if) there are ties in the team's record.

- The CFL nominally awards three playoff berths per division while the NFL awards a playoff berth to each of its division winners (four per conference) and three wild card berths per conference (previously only two wild card berths before the 2020 season). The CFL allows the possibility of a fourth place team in one division to "cross over" in place of the third place team of the other division, but only if it has a better record than the third place team. Also, even though the CFL has an unequal number of teams per division there is no possibility of the fifth place team in the West Division qualifying, even if it finishes outright fifth or sixth overall. By contrast, an NFL team finishing second in its division receives no special advantage should it finish tied with a third place team in another division for the final wild card berth. Beyond that, the tie-breaking criteria are radically different (although they both culminate in an as-yet-unused coin toss should all criteria be exhausted). For example, the CFL's first tie-breaker is number of wins, whereas number of wins is not an NFL tie-breaking criterium in itself, meaning an NFL team with no ties would have neither an advantage nor a disadvantage over another team with one less win and two ties, assuming they played the same number of games.

Strategic and tactical differences

Although the rules of Canadian and American football have similarities, the differences have a great effect on how teams play and are managed.

Red-zone management

The red zone is an unofficial term designating the portion of the field between the 20-yard line and the goal line. Due to the goalposts' being on the goal line in Canadian football, teams must avoid hitting the goalposts. Thus most touchdown throws are aimed away from the centre portion of the end zone. In the CFL, the goalposts have the same construction as the NFL posts, with the centre post being about 2 yards deep in the end zone. It is extremely rare for CFL passes to hit any part of the posts. When this occurs, a dead ball results. Occasionally, receivers can use the post to good effect in a 'rub' play to shed a defender. End zone passing becomes even more complicated when the corners of the end zone are truncated, as is the case at stadia where the field is bounded by a running track. However, the offensive team enjoys a counteracting advantage of end zones more than twice the size of those in American football (20 yards with a wider field), significantly expanding the area that must be covered by the defensive team and also allowing the freedom to run some pass patterns not available in American football's red zone. Moreover, the rule requiring only a single foot to be in bounds upon pass reception in Canadian football further stretches the amount of area that the offenses have to work with. NFL offenses generally try a run between tackles when on the one-yard line. CFL offenses make similar attempts on first down on the one-yard line, but second and third down attempts, if required, can be much more varied than their NFL counterparts.

Special teams

The frequency of punts is highly dependent upon the success, or lack thereof, of the offense. Punt returns are ubiquitous in Canadian football because the "no-yards" rule permits virtually every punt to be fielded and returned. Moreover, if the kicking team punts the ball out of bounds in an attempt to forestall a return and the ball goes out of bounds between the two 20-yard lines without touching the ground first, a 10-yard penalty is assessed and the ball advanced from where it left play, or the kicking team is backed up 10 yards and must replay the down.[36] "Shanked" punts are therefore extremely costly to the kicking team. Though missed field goals may be returned in both national rule sets, the deeper end zone and goal post positioning make this much more common in Canadian rules. TSN on-air analysts state that they are the single play-from-scrimmage most likely to result in a touchdown. This set of special teams play (field goal return units) are rare in the American game to the point where a returner is not a standard part of a defensive field goal unit and will only be seen in unusual circumstances, with one especially notable example being the famous "Kick Six" college football game in 2013. Canadian kickoffs rarely result in a touchback, so special teams are more prominent in that area of the game as well. The difference in the games' final minutes procedures make comebacks—and the need for an onside kick 'hands' team—more prominent as well. The rule regarding last touch of the ball before leaving the play of field, rather than American football's last possession rule, makes the onside kick more likely to be successful as well. The most complex coaching job in Canadian football is said to be that of special teams co-ordinator. As many as 40 of a CFL roster of players may have a special teams role because of the wide variety of possible situations. In 2014 and 2015, the Edmonton Eskimos even used their third-string quarterbacks (Pat White in 2014 and Jordan Lynch in 2015[37]) as part of their kick and kick-coverage teams. This is highly unusual, as quarterbacks are generally discouraged from making contact plays. Kick returning was a duty generally handled by a player with another role, such as receiver or defensive back. Henry "The Gizmo" Williams[38] was the first player designated by telecasts as "KR" for a kicker returner position as his duties were almost entirely for that role, and referring to him as "WR" for wide receiver was increasingly seen as anachronistic. By far the greatest kick returner in professional football history, Gizmo Williams had more returns for touchdowns called back for infractions than any other player has ever scored (28: 26 punts, 2 kick-offs). No NFL player has enjoyed similar success and the careers of such specialists (like Devin Hester) come nowhere near to matching the impact on the game that such players have in the CFL.

Management of offensive drives

Canadian teams have only three downs to advance the ball ten yards compared to four downs in the American game. With one fewer down, Canadian teams must try for the big gain. For this reason, Canadian teams usually prefer passing over rushing to a greater extent than American, since pass attempts generally tend to gain more yards than rushing. This makes the action in Canadian football more open than is the case in the American game. Offensive drives (continuous possession of the ball) tend to be shorter.

Having three downs on a much longer and wider field with unlimited backfield motion results in Canadian teams requiring faster, more nimble athletes (comparatively) than their American counterparts. Paradoxically, this makes Canadian defense better at defending rushing plays. Rushing plays tend to be unlikely to produce a full ten-yard gain, and if correctly anticipated by the defense, much gain at all. The fewer downs means that an unsuccessful rushing play leaves an offense to have a single play to make comparatively longer first down yardage, so rushing plays are less favored unless the team on offense is actively managing the clock while maintaining the lead.

Pundits often like to claim that a Canadian team that rushes for 100 yards or more per game is likely to win, but the reality is winning teams rush the ball in defense of their leads, and not as a tactic to produce drives that lead to points unless they are markedly superior to their opponents. The larger field generally permits greater YAC (yards after catch) on each individual catch, where the NFL produces passing plays that either result in immediate tackles for relatively few YAC, or huge gains resulting from missed tackles or broken coverage.

In theory, an NFL team taking possession on their own one-yard line, using three downs for each first-down conversion and the full 40 second clock could run 27 plays and consume a full 18 minutes of clock time covering the 99 yards. A CFL team doing something similar (two plays per conversion, 20 second clock, average 10 seconds of clock time while the officials reset the ball between plays, 109 yards) would run 24 plays and consume 12 minutes of clock at the most.

One other notable difference is the propensity of CFL quarterbacks to rush the ball, both by design and as a result of reacting to the defense. Damon Allen[39] (the younger brother of Pro Football Hall of Fame running back Marcus Allen) had 11,920 rushing yards to go along with 72,381 passing yards in his 23-year career and actually sits third overall in career rushing yards. Contrast that with Randall Cunningham's 4928 yards over 16 seasons.[40] 1000-yard rushing seasons for CFL quarterbacks have occurred,[41] and 400-yard seasons for playoff-bound teams' starting quarterbacks, if they remain healthy for the entire schedule, are not unusual.

Backfield motion

Perhaps the greatest difference arises due to the virtually unlimited movement allowed in the defensive and offensive backfields on a play from scrimmage in the Canadian game vs. very restricted offensive movement in the American game. Combined with the much larger field size, this difference changes the skillsets required of the athletes.

Canadian wide receivers, safeties and cornerbacks are far enough from the point where the ball is snapped that they rarely participate in rush offense or defense. Linebackers can be called upon to successfully defend running backs sent to receive passes. There is therefore a much greater premium placed on athletic speed, with former Edmonton Eskimos GM and former wide receiver Ed Hervey (6 ft 0 in [183 cm], 195 lb [88 kg], All-American at USC in the 200 meter) and Malcolm Frank[39] (5 ft 8 in [173 cm] 170 lb [77 kg]) being prototypical for the CFL. The offence has many more formation options and starting positions, forcing the defence to anticipate more possibilities. Seven of the 12 men on a CFL offense (typically the five linemen and the wide receivers) must be at the line of scrimmage at the time of the snap, and the other five must be at least one yard behind the line. Only the quarterback and linemen must be motionless at the time of the snap, allowing up to six players to be moving toward or along the line at varying speeds (typically the wide receivers are still or at a walking pace at the snap to ensure they are at the line of scrimmage.)

Late comebacks

In both the college and pro games, an offensive team with the lead has more difficulty in running out the clock in the Canadian game.

In the Canadian Football League, the clock is stopped while the officials place the ball, and then they whistle the game clock and play clock to begin in the last minutes of a half; whereas in the National Football League the clock remains running while the officials set the ball (dependent upon the result of the previous play—penalty, incomplete pass, out-of-bounds, or tackle inbounds in both leagues) while the play clock of 40 seconds runs down. The game clock only begins again when the play is whistled in, for an inbounds tackle, or at the snap of the ball for the other outcomes in the CFL. A team that is ahead has one fewer opportunity to kill clock time in the Canadian game with three downs, and can only take the play clock time (20 seconds) and the length of the play itself off the clock with each down. On the other hand, Canadian teams only receive one timeout per half, as opposed to three in American football. After the three-minute warning, a penalty of a loss of down (on first and second down, 10 yards on third down) results for failing to start the new play in time (time count violation).

Additionally, if a Canadian team commits a time count violation on third down, the referee has the right to require that it legally start a new play before the play clock expires, and can award possession to the defending team if another time count is committed. Moreover, in any quarter, when the game clock expires while the ball is dead in Canadian football, a final play must be run with "zeros on the clock" before the quarter ends, whereas in American football the expiration of time while the ball is dead immediately ends the quarter (including overtime periods in such cases where those periods are timed). In American football, it is common (or even, arguably, expected) for teams including coaching staffs and other such personnel to come on the field in order to shake hands, etc. before the game clock officially expires, especially in cases where the trailing team does not have possession of the ball, has no timeouts left and the result of the final play of the game left the clock running with less than forty seconds left.

The main caveats are that in all gridiron codes, a half cannot end on any penalty accepted by the non-penalized team even if there is no time remaining on the clock, and a team may always elect to attempt a conversion after a touchdown even if time is expired, so it is always possible for a final play to run with "zeros on the clock" under such circumstances. If a team that is trailing in the CFL can begin to produce two-and-outs on defense and efficient scoring drives on offense, 14 and even 17 points can be successfully scored in the final three minutes. This comeback proclivity is so pronounced that the CFL uses it for marketing purposes: No Lead Is Safe.[42]

See also

- American football

- American football rules

- National Football League (NFL)

- Canadian football

- Canadian football rules

- Canadian Football League (CFL)

- Comparison of American football and rugby league

- Comparison of American football and rugby union

- Glossary of American football

- Glossary of Canadian football

- Rugby football

References

- "Canadian Football Timelines (1860–present)". Football Canada. Archived from the original on 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- Fitz-Gerald, Sean. "CFL ends working agreement with NFL". www.nationalpost.com.

- O'Leary, Chris (10 June 2016). "Argonauts eager to open the BMO Field chapter of their history" – via Toronto Star.

- "Professional (NFL) Football Field Dimension Diagram - Court & Field Dimension Diagrams in 3D, History, Rules – SportsKnowHow.com". www.sportsknowhow.com.

- Grasso, John (13 June 2013). Historical Dictionary of Football. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810878570 – via Google Books.

- "Untitled Document". www.cflapedia.com.

- "FAQ about Equipment on CFLdb". Cfldb.ca. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- "CFL to Roll Out New Ball for 2018 Season" (Press release). Canadian Football League. March 19, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-11. Retrieved 2013-08-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://static.nfl.com/static/content/public/image/rulebook/pdfs/2012%20-%20Rule%20Book.pdf

- Bender, Jim (2008-05-29). "Getting feel for CFL". Winnipeg Sun. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- http://cflofficials.ca/docs/2015%20Rule%20Book%20English.pdf Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine (p 37)

- "Rule 4 - Scrimmage - Section 6 - Series Of Downs - 2017 Official CFL Rulebook on CFLdb". cfldb.ca.

- Canadian Football League. "Rule 4, Section 1, Article 3: Scrimmage Zone". The Official Playing Rules of the Canadian Football League 2018. The Canadian Football League Database. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Rule 4: Scrimmage. Canadian Football League (2005). CFL Official Playing Rules 2005. Toronto, Ontario: Canadian Football League. p. 81.

- Beamish, Mike (2009-08-11). "Border man stands on guard for BC Lions". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 2009-08-14. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- Section 4, Article 1

- Goodell, Roger. "2016 Official Playing Rules of the National Football League" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "FAQ about Game Rules and Regulations on CFLdb". cfldb.ca.

- "Rule 1, Section 7, Article 9: Time Count" (PDF). The Official Playing Rules for the Canadian Football League 2015. Canadian Football League. pp. 18–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- "NCAA Football rules committee boosts safety rules". NCAA. 2003-02-18. Archived from the original on June 28, 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- Canadian Football League (2008). "Rule 3: Scoring". CFL Official Playing Rules 2008 (PDF). Toronto: Canadian Football League. p. 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- The Stampeders attempted this on the final play against the Argonauts, Sept 21, 2013. Stampeders Come Short.

- "Wacky finish as Als beat Argos on final play". The Canadian Press. 2010-10-29. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- "Video". YouTube.com. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- "2009 CFL Rule Changes". The Game. Canadian Football League. Archived from the original on 2009-07-19. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- Litke, Jim (August 20, 1989). "They're Not All Kicking and Screaming Over the Absence of Tee". Los Angeles Times. Associate Press. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

The NFL allows the use of tees as high as 3 inches for kickoffs, but has never allowed them for field goals and PATs. The pro league, which began to declare its independence from the college game with a number of rules changes beginning in the mid-1930s, also has refused to widen the goal posts.

- "NCAA rules change will ban tees on FGs, PATs - The Tech". tech.mit.edu. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- "No More Tee Party". CNN. September 4, 1989.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about Equipment". Retrieved 2019-10-03.

For place kicks (field goal and convert attempts) the kicking tee platform or block can be no higher than one inch in height as per Rule 5, Section 1, Article 3 of the CFL Rulebook. For kickoffs, the ball may be held or placed on a tee such that the lowest part of the ball is no higher than three inches off the ground; Kicking tees are not required to be used. Kickers may kick off the ground if they desire.

- Johnson, Greg. "Targeting protocols approved for football". NCAA. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Florio, Mike (April 7, 2019). "Spring League returns with revolutionary overtime idea". Profootballtalk.com. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "XFL Rules". XFL.com. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- "ESPN - Owners table reseeding playoffs proposal; pass other rules - NFL". Sports.espn.go.com. 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- "Canadian Football League Introduces Key New Rule Changes for 2015 - American Football International". 21 April 2015.

- "2011 CFL rule changes approved - CFL.ca". 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-04-17. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- "Eskimos QB Jordan Lynch will take over duties originally handled by former QB White". 26 June 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2015-09-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "CFL.ca - Official site of the Canadian Football League". CFL.ca.

- "NFL: Top Ten Rushing QBs 100521 - NFL - ESPN". ESPN.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2008-12-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://cfl.ca/noleadissafe%5B%5D