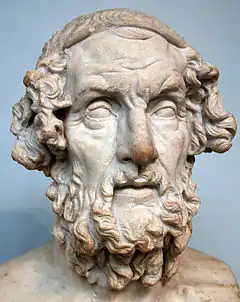

Contest of Homer and Hesiod

The Contest of Homer and Hesiod (Greek: Ἀγὼν Oμήρου καὶ Ἡσιόδου, Latin: Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi or simply Certamen[1]) is a Greek narrative that expands a remark made in Hesiod's Works and Days[2] to construct an imagined poetical agon between Homer and Hesiod. In Works and Days, Hesiod (without mentioning Homer) claims he won a poetry contest, receiving as the prize a tripod, which he dedicated to the Muses of Mount Helicon. A tripod, believed to be Hesiod's dedication-offering, was still being shown to tourists visiting Mount Helicon and its sacred grove of the Muses in Pausanias' day, but has since vanished.[3]

Manuscripts

The Certamen itself is clearly of the second century A.D., for it mentions Hadrian (line 33). Friedrich Nietzsche deduced[4] that it must have an earlier precedent in some form, and argued that it derived from the sophist Alcidamas' Mouseion, written in the fourth century B.C. Three fragmentary papyri discovered since have confirmed his view.[5] One dates from the third century B.C.,[6] one from the second century B.C. [7] (both of these contain versions of the text largely agreeing with the Hadrianic version) and one, identified in a colophon text as the ending of Alcidamas, On Homer (University of Michigan Pap. 2754)[8] from the 2nd or 3rd century AD.

That the story derives in part from the classical period or earlier (and before the Mouseion) has been shown most clearly[9] by two lines from its riddle passage that appear in Aristophanes' Peace[10] "It does seem easier to suppose that Aristophanes was quoting a pre-existing text of the Certamen than that Alcidamas appropriated the lines from Aristophanes for a Certamen-like story in his Mouseion," R.M. Rosen observes.[11] The more profound influences of some version of the Contest on Aristophanes' The Frogs has been traced by Rosen, who notes the clearly traditional organising principle of the contest of wits (sophias), often involving riddling tests.

Content

The site of the contest is Chalcis, in Euboea. Hesiod tells (Works and Days lines 650–662) that the only time he took passage in a ship was when he went from Aulis to Chalcis, to take part in the funeral games for Amphidamas, a noble of Chalcis. Hesiod was victorious; he dedicated the prize, a bronze tripod, to the Muses at Helicon.[12] There is no mention of Homer.

In Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi the winning passage that Hesiod selects is the passage from Works and Days that begins, "When the Pleiades arise..." The judge, who is the brother of the late Amphidamas, awards the prize to Hesiod. The relative value of Homer and Hesiod is established in the poem by the relative value of their subject matter to the polis, the community: Hesiod's work on agriculture and peace is pronounced of more value than Homer's tales of war and slaughter.

The work also preserves 17 epigrams attributed to Homer. Three of these epigrams (epigrams III, XIII and XVII) are also preserved in the Contest of Homer and Hesiod and epigram I is found in a few manuscripts of the Homeric Hymns.[13]

The short text[14] begins with brief sketches of the poets' lives, including their parentage and birth. It then describes the contest itself, which consists of challenges and riddles that Hesiod poses, to which Homer improvises masterfully, to the applause of the on-lookers, followed by their recitation of what they considered their best passage and the awarding of the tripod to Hesiod; this takes up about half the text and is followed by accounts of the circumstances of their deaths.

Modern editions

One modern edition of the Greek text is in volume 5 of T.W. Allen's Oxford Classical Text of Homer (1912).

An edition with Greek text and English translation (on facing pages) by Hugh Evelyn-White was published in 1914 as part of the Loeb Classical Library volume titled Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica, and is now in the public domain and available online.[15]

Notes

- Conventionally Greek works did not bear titles; the application of a Latin title to Greek works is an ancient tradition: this Latin title was applied in the Renaissance and is a shortened version of the title in the Greek: Concerning Homer and Hesiod and their descent and their contest.

- Works and Days, lines 650−662

- Pausanias, Description of Greece ix.31.3.

- Nietzsche, "Die Florentinischer Tractat über Homer und Hesiod", in Rhetorica (Rheinisches museum für philologie) 25 (1870:528-40) and 28 (1873:211-49).

- Koniaris 1971, Renehan 1971, Mandilaras 1992.

- Flinders Petrie, Papyri, ed. Mahaffy, 1891, pl. xxv.

- First published by B. Mandilaras,Platon 42 (1990) 45-51.

- Winter, J. G., "A New Fragment on the Life of Homer' Transactions of the American Philological Association 56 (1925) 120-129 ).

- The evidence for a 5th-century version of Certamen is summarised by N.J. Richardson, "The contest of Homer and Hesiod and Alcidamas' Mouseion", The Classical Quarterly New Series 31 (1981:1-10).

- lines 1282-83.

- Ralph Mark Rosen. "Aristophanes' Frogs and the Contest of Homer and Hesiod", Transactions of the American Philological Association 134.2, Autumn 2004:295-322. (on-line text)

- The Contest is adduced by Richard Hunter, (The Shadow of Callimachus: Studies in the Reception of Hellenistic Poetry at Rome (Cambridge University Press) 2006:18) as an expression of the cultural conditions behind the conspicuous absence of Homer at Helicon.

- Hesiod; Homer; Evelyn-White, Hugh G. (Hugh Gerard), d. 1924 Hesiod, the Homeric hymns, and Homerica London : W. Heinemann ; New York : Putnam p.467

- approximately 338 lines.

- See References section for links.

References

- Evelyn-White, Hugh G. The Contest of Homer and Hesiod. In: Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica, pp. 565−597. New York: Putnam, 1914. (English-text only version at the Internet Sacred Text Archive).

- Ford, Andrew. 2002 The Origins of Criticism: Literary Culture and Poetic Theory in Classical Greece (Princeton University Press).

- Graziosi, Barbara, 2001. "Competition in Wisdom" in F. Budelmann and P. Michelakis, eds. Homer, Tragedy and Beyond: Essays in Honour of P.E. Easterling (London) pp 57–74.

- Griffith, Mark. 1990. "Contest and contradiction in early Greek poetry" in Mark Griffith and Donald Mastronarde, eds. Cabinet of the Muses: Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer (Atlanta) pp 185–207.

- Kahane, Ahuvia. Diachronic Dialogues: Authority And Continuity In Homer And The Homeric Tradition

- Koniaris, G.L. 1971 "Michigan Papyrus 2754 and the Certamen", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 75 pp 107–29.

- Mandilaras, Basil. 1992. "A new papyrus fragment of the Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi"in M. Carpasso, ed. Papiri letterari greci e latini (ser. Papirologia lupiensia) I:Galatina pp 55-62.

- Renehan, Robert. 1971. "The Michigan Alcidamas-Papyrus: A problem in methodology" Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 75 pp 85–105.

- Richardson, N. J. "The Contest of Homer and Hesiod and Alcidamas' Mouseion." The Classical Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 1, 1981, pp. 1–10.

- Rosen, Ralph M. "Aristophanes' Frogs and the Contest of Homer and Hesiod." Transactions of the American Philological Association. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Uden, James. 2010. "The Contest of Homer and Hesiod and the Ambitions of Hadrian", "Journal of Hellenic Studies", 130 pp 121-135.

- West, M.L. 1967. "The Contest of Homer and Hesiod", The Classical Quarterly New Series 17 pp 433–50.