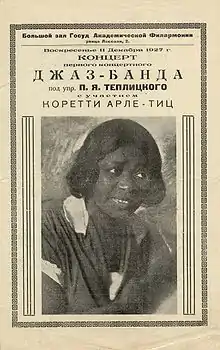

Coretti Arle-Titz

Coretti Genrichovna Arle-Titz (Russian: Коретти Арле Тиц) (December 5, 1881 – December 14, 1951), known professionally as Corette Alefred, was an American-born jazz, spiritual and pop music singer (lyrical and dramatic soprano), dancer, and actress in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

Coretti Genrichovna Arle-Titz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Corette Elisabeth Hardy 5 December 1881 Churchville, New York, U.S. |

| Died | 14 December 1951 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | American, Russian |

| Occupation | Dancer, singer, actress |

| Years active | 1902–46 |

| Spouse(s) | ? Utin (m. 1908–1914)Boris Borisovich Titz

(m. 1917) |

| Children | 2 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels | Gramplasttrest Record Trust |

Early life

Coretté Elisabeth Hardy was born on December 5, 1881 (or 1883) in Churchville, New York to Carrie Carter and Thomas J. Hardy. Thomas migrated north to Brooklyn around 1875 from Petersburg, Virginia. During the summer of 1879, he met and soon married Carrie Carter (another migrant from Richmond, Virginia).

In April 1880, while employed as a servant for the Walach family (a German family living in Long Island), Carrie bore him a son. Unfortunately, the child did not survive and the couple traveled north to the township of Churchville, where Carrie bore two children, Coretté (1881) and Anna (b. 1884).

Sometime between 1886–1888, the family returned to Manhattan, where eight more children were produced, although Edward (b. 1889), Isabella Clara (b. 1892), Miles (b. 1895) were the only ones to survive childhood. The family resided at 140 West 19th Street in the busy Midtown district.

Early 1900, the family relocated to 448 West 54th Street in the heavily industrialized Hell's Kitchen district. Every tenement building and shantytown was filled Irish immigrants, who had fled from Ireland's Great Famine to seek employment on the Hudson River docks or the railroads. Many of those unfortunate enough to reside in this congested poverty-infested neighborhood turned to gang life. By April 1900, 18-year-old Coretté Hardy found employment as a copyist (transcribing documents) and used the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church Choir as her only musical outlet.

Career

Early career (1901–1907)

In April 1901, Coretté noticed an advertisement in the New York Herald posted by German theatrical impresario, Paula Kohn-Wöllner, seeking seven African-American women with the ability to sing and dance for a concert tour of Germany.[1] Hardy replied to the advert and was promptly accepted. Kohn-Wöllner, who had previously managed two theatrical troupes in the 1890s in Leipzig and Chemnitz, had made a trip to New York to visit her two married sisters, when she got the idea to organize a Negro theatrical troupe to tour across Europe. Soon the troupe consisted of Ollie Burgoyne (a 26-year-old singer from the Oriental America show), Fannie Wise (a 19-year-old singer from Brooklyn), Florence Collins (a 26-year-old pianist from Kentucky), Alverta Burley (a 19-year-old from Baltimore), S.T. Jubrey (a 32-year-old housewife from Virginia) and Emma Harris (29-year old housekeeper from Brooklyn). Unfortunately, 19-year-old Coretté Hardy, although accepted, was to be left behind as a replacement in case any of the other women decided to quit the newly christened "Louisiana Amazon Guard" troupe. On April 10, the six women were brought to the Passport Office to apply for their first passports. After two weeks with Ms. Kohn-Wöllner paying for all six of the women's travel expenses, they boarded on the S.S. Deutschland, heading for Germany.[1]

On April 28, 1902, Coretté received her first passport and around late-May, accompanied by Fannie Smith (from Philadelphia) traveled across the Atlantic to join the Louisiana Amazon Guard troupe in Europe.[2] While traveling abroad, she changed her name to Coretté Alefred, for unknown reasons. For five successful months, the troupe traveled across central Europe, performing in Zurich, St. Gallen, Munich, Leipzig and Dresden. On November 1, 1902, during an engagement in Dresden, the women severed relations with their German impresario and sued her for financial exploitation and mismanagement. Ollie Burgoyne was elected as the troupe manager. On November 16, now as the "Five Louisianas", the troupe relocated to Berlin, where they began a short German tour for the next four months. In March 1903, during another Dresden appearance, Ollie Burgoyne and Florence Collins renewed their passports and departed for London to join the cast of Hurtig & Seamon's "In Dahomey", which opened the following month at the Shaftesbury Theatre. Possibly under the management of Emma Harris, the troupe continued touring Germany for another three months before departing for the Russian Empire. After receiving a passport from Berlin's American Embassy (July 10, 1903), the troupe traveled northwest to Saint Petersburg, to appear for two months at the popular Krestovskiy Garden Amusement Park, where they opened on July 19. On September 29, the troupe opened in Moscow at Aumont's French Theater for another two months billed as the "4 Ebony Belles". During the winter of 1903, the Louisiana Amazon Guard (Ebony Belles) finally dissolved. Alverta Burley married African-American entertainer Oliver E. Brodie and the couple toured as "Brodie & Brodie". Harris convinced Coretté Hardy and Fannie Smith to remain in Russia with her and they formed the "Harris Trio". For the next six months, the trio performed between Saint-Petersburg and Moscow. In March 1904, the duo became the "Harris Trio" with the addition of Fannie Smith, and together they departed for Helsinki with an engagement at the illustrious Hotell Fennia, where Finnish high society enjoyed mingling.

Around May 1904, the Harris Trio, together with Ollie Bourgoyne and Jennie Scheper (from the Florida Creole Girls) formed a new company known as the "Creole Crackerjacks Troupe" (or the Creole Belles) and continued touring the principal Russian cities. On January 22, 1905, while attending a party, hosted by popular American jockey, William Caton, in central Saint-Petersburg, the women witnessed the Bloody Sunday riots outside the Tsar's palace and across the city. After nine months, the troupe dissolved and Coretté, Emma and Fannie immediately returned to Moscow, where they resumed working at the Aumont Theater for a few weeks. The trio dissolved in February,[1] Emma becoming a solo artist and Coretté and Fannie forming the "Koretty & the Creole Girl" song-and-dance duo. For the next 13 months, Coretté and Fannie toured between St. Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw.

From 1906–1907, during the height of the 1905 Revolution, there's no record of the two women. Most likely they continued performing across the Russian Empire. On September 25, 1907, Coretté resurfaced in Moscow, applying for a new passport. By this point, Fannie Smith was in Saint-Petersburg, with her new lover and dance partner, Robert Ledbetter (the couple would return to Philadelphia in September 1914).

K. G. Utina (1908–1916)

In late 1907 or early 1908, after a five-month engagement, 26-year old Coretté married a nobleman named Utin and moved into his home in central Saint-Petersburg. It is currently unknown which member of the Utin household Corette, although it's been narrowed down between the wealthy prosecutor and senator, Sergey Yakovlevich Utin or his cousins, Vladimir Lvovich Utin (a lawyer) or Alexei Lvovich Utin. The Utin family, originally successful Jewish merchants, after converting to the Eastern Orthodox Church in the 1850s, became an extremely wealthy bunch of bankers, business tycoons (Baku Oil Company), lawyers and politicians that owned (or built) an abundance of property in the Russian capital. At the elaborate dinners organized on the numerous family homes and estates, members of government, businessmen, writers, and scientists were frequent guests. Everyone in the family was exceptionally educated, ambitious and surprisingly radical in their thinking. The family had taken part in the 1861 student movement and the Decembrist Revolution. Despite the Russia's national anti-Semitic attitudes, the family never forgot their Jewish heritage and maintained positive relations with Russian Jews. From the beginning, the marriage was marred by jealousy from her in-laws who felt that her husband had married beneath him. He was accused of renouncing his family for an African-American cabaret artist.

Immediately after the wedding, she Russified her name as Koretti Genrichovna de Utina (Russian: Коретти Генриховна де-Утина) and possibly even petitioned to St. Petersburg's Ministry of the Interior to receive Russian citizenship, as she suddenly stops bothering to renew her passport and the American Embassy no longer keeps any records of her. Coretti returned to the stage as M-lle К. Г. Утина (Mademoiselle K. G. Utina). Performing as Russian Romance songs with her dramatic soprano voice, she was sometimes also billed as the Indian Nightingale or the Beautiful Creole.

From 1908-1909, she appeared at the New Summer Garden Theater, a wooden theater located on 58 Bassenaya (now 58 Nekrasov) that staged operas and operettas. In August 1908, she appeared in Franz von Suppé's operetta, "Boccaccio" in the minor role as Sisti, a servant (August 31, 1908). The following year, she had another minor role in "Letim", a three-act Italian operetta (July 16–31, 1909). Her performances were sparse between 1908-1910, as she bore two children for her husband.

In October 1910, after the New Summer Garden Theater was destroyed by a fire, Coretti returned to New York after eight years abroad and visited her family at 218 West 64th Street. She found the family had fallen upon hard times and relocated to the dangerous San Juan Hill district. Her father was laboring as an elevated railway porter, her mother still scrubbing floors for the white families and her brother Edward selling newspapers on every street corner across San Juan Hill. Young Clara and Miles were still attending the nearby school. Although the family was happy to reunite with Coretti, the joy quickly dissolved whenever the subject of her recent marriage came up. Her parents weren't too pleased nor did they accept their daughter's marriage.

Soon newspapers began reporting about the musical appearances of "Coretta de Outine of Saint-Petersburg". An acquaintance of Coretti's, Richetta G. Randolph helped to arrange her appearances in hotels, clubs, churches and other social functions around the city. On October 27, Coretti appeared in the musical cantata, "Jephthah and his Daughter" held at the Mt. Olivet Debating Club. After the performance, Toastmaster Allison presented Coretti with a gold pin as a token of appreciation for her performance. The following month, on November 28, at the Jubilee Quartette Reception held at the Hotel Maceo, Coretti beautifully performed, 'Do not say that the grave ends all'. Eventually, the tour came to a halt as Coretti could no longer stand America's prejudiced attitudes, especially since she had become so accustomed to being able to frequent any restaurant or public space that she wanted in Europe. On December 5, Ms. Randolph threw Coretti a large birthday/going away party at her apartment at 248 West 53rd Street before she boarded a ship five days later back home to Russia.

Back home, while her husband was away, Coretti sent the children away to relatives in Moscow and embarked upon her first solo tour across the Russian Empire. In May 1911, she appeared at Saint-Petersburg's Jardin d'Hiver Theater (previously known as the Apollo Theater), located at Fontanka Embankment 13. Two months later in July, she was in Kiev at the Apollo Garden Theatre. Located at 8 Meringovskaya St, a three-story stone building, known as the Noble Club, housed the Apollo restaurant with its open-air stage that showcased variety, opera and theatrical productions daily. The following month, she arrived just outside the Latvian capital of Riga in the seaside resort town of Jūrmala. The town, with its wooden art nouveau villas, sanatoriums and long sandy beaches was already a popular tourist destination. In the Edinburgh neighborhood (now Dzintari), the Rigasche Rundschau newspapers advertised her debut at the Edinburger Sea Pavilion on August 10. Rigasche Rundschau:

"Mlle Outina, the Indian Nightingale. The fact that a Black woman is a Russian Romance singer, you've probably never heard of such and yet she behaves as so. Originating from the United States, Fraulein Outina came to Russia, where she was the main attraction in the south (Ukraine), Moscow and St. Petersburg, and was received enthusiastically everywhere. Here, too, she had great applause yesterday upon completing her first song, because she has good qualities and a beauty for her race. It was pleasant to say that her manner and costume were free from any theatrical gimmicks and completely natural and discrete. Furthermore, the directors succeeded in accordance with general wishes to extend her stay for another five days."

From January 14–24, 1912, Coretti was in Kharkov performing at V. Jatkin's scandalous Villa Jatkina cabaret, located on the Kharkov embankment along the Kharkiv. During her two-week engagement, she received word from friends in Moscow about the sudden untimely death of one of her children. On January 25, 1912, several newspapers reported that a "Mlle. Outina, a Black woman married to a Russian and follower of the Lutheran religion, was sent to Alexander's Hospital for a suicide attempt". Coretti attempted suicide at her Kharkov hotel, drinking an Ammonia concoction. However, she called for an ambulance immediately afterwards. After being hospitalized for three days, Jatkin replaced Coretti with Afro-American dancer Robert (Bob) Hopkins and she returned to Moscow to bury her child. Coretti resumed touring shortly afterward and continued until early-1913.

Conservatory and the Fine Arts Society (1913–1916)

In September 1913, Coretti enrolled at Saint Petersburg Conservatory for musical and voice training under professor Elisabeth F. Zwanziger, with whom she also received private lessons.[3] For a woman who, despite a ten-year residence in Russia, could hardly read in the Russian language, it is difficult to understand how she was able to secure a position in such a prestigious school.

Around this time, during a trip to Finland, 32-year old Coretti met another student from the conservatory, 23-year old, blond-haired Boris Borisovich Titz. The Titz family, with origins traced back to Bavaria, made their way to Russia when concert artist, Augustus Dietz toured Russia in 1771. Augustus received an offer to remain in St. Petersburg as a member of Tsarina Catherine's Imperial court orchestra, where he amassed a huge fortune. Over the years, the Dietz family name eventually developed into Titz. Like most bourgeoisie families, the Titz's valued education, particularly musical education to continue their reputation as a noted musical family. On October 29, 1890, Boris Borisovich was born to Anna Vasilievna and Boris Nikolaevich Titz on the family estate in the village Vysh-Gorodishche deep in the Tver province, just northwest of Moscow. He was the third of four children, Olga (1880), Natalia (1885) and Alexey (1895). By 1900, the family left Vysh-Gorodishche for St. Petersburg where they resided at 36 V.O. ya Liniya 3 on Vasilyevsky Island. The Island was the center of the majority of St. Petersburg's scientific and other educational institutions. The early 20th century brought about an active housing construction boom as new buildings, particularly industrial plants were constantly appearing. In 1908, months before Boris graduated from the Karl May School (and received a gold medal), Boris Nikolaevich Titz died on March 23, 1908 and after a funeral at St. Andrew's Cathedral was buried at Smolensk Orthodox Necropol. Immediately afterward, the family's fortune began to dwindle. The following year, as young Boris enrolled himself into the law facility of the St. Petersburg Imperial University, where he began offering private math and Latin lessons for classmates to pay for his classes. He completed his university course in 1912 with his thesis Peculiarities of protection of possession under Russian Law. Since he showed a keen interest in music and singing since childhood, instead of pursuing a career in law, he immediately afterward enrolled into the esteemed St. Petersburg Imperial Musical Conservatory, where he studied piano under professor Anna Nikolaevna Esipova until his graduation in 1914.

Around December, while studying at the conservatory, she was soon introduced to an esteemed member of the Petrograd Conservatory and pianist, Nikolay Burenin, and it wasn't long before he offered her an interesting proposition in joining his latest venture, the Society of Fine Arts. Burenin and fellow pianist (and director of the St. Petersburg Theater of Musical Drama) Mikhail Bichter organized the Society in 1911 under the League of Education and received permission in early 1913 from E.P. Karpov (chief director of Imperial Theaters) to turn the organization into an independent society with its own charters. The organization was divided into four sections: Musical, Dramatic, Literary and Artistic (sculpture and painting). The musical section, headed by Burenin, consisted of more than a hundred singers, pianists, violinists, cellists, musicologists and professors from the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Around the Russian capital, the Society arranged "literary & musical mornings", which gathered large audiences of five to six hundred people consisting of workers and peasants. The carefully organized program promoted the best works of Russian romance, folk and classical music such as the works of Glinka, Tchaikovsky and Glazunov. The majority of the public concerts were usually held in the hall of the Tenishev Secondary School (at 33-35 Mokhovaya) as well as at the Zemsky School, Worker's Clubs and the Labor Exchange. Touring with the Society of Fine Arts, Coretti soon discovered that she was performing before audiences of revolutionaries who used the concerts as fronts for their anti-government meetings. A significant part of the income from the paid concerts went to the Bolshevik party. Through the underground revolutionary Burenin, Coretti was introduced to Countess Sofia V. Panina, F.I. Drabkina, V.V. Gordeeva, A.I. Mashirov and many other revolutionary actors, composers, musicians, artists and writers. From her new Bolshevik acquaintances, she became more familiar with the unrelenting fury and brutality of the Tsarist gendarmerie and Okhrana (secret police) upon the lower classes. The leaders of the proletariat were shadowed, hunted and sent to rot in distant Siberian prisons for their illegal underground activities.

From late April to early May 1914, the underground Bolshevik newspaper, Path of Truth, announced the "Literary & Musical evenings" at the Ligovsky People's House, located on 63 Tambovskaya Lane, on Petrograd's outer edges near the numerous factories and industrial plants. It was there every night, as the band struck up the music, Coretti emerged upon the makeshift stage inside the industrial plant. Before a backdrop of a blue sky and endless grain fields, Coretti, clothed in a tattered dress and carrying a sickle, began singing a lamentable song of anguish, pain, and suffering which was so dramatic and powerful that it touched the hearts of every worker in the audience that night. During World War I, in-between her studies, Coretti toured around Petrograd with the Fine Arts Society, appearing in Schools, Auditoriums, Military Hospitals and Factories. During this time, the Utin household was filled with drama and turmoil. Mr. Utin was spending long periods away from home and whenever he returned, Coretti tormented him with questions. The arguments eventually culminated with divorce, especially as Utin was constantly under pressure to do so from his family.

From 1915–1917, separated from her former husband and her only remaining child, Coretti began dating Boris Titz and possibly moved in with him at his apartment at 20, V.O. ya Liniya 9, where he supported himself by offering piano lessons and composing music.

Early 1916, the Fine Arts Society held a concert held at the Tenishev School, with the participation of Maxim Gorky who gave a fiery propaganda filled speech despite the presence of the secret police.[4] A financially successful author, playwright and editor, Gorky (born Alexei Peshkov in 1868) was well noted for publicly opposing the Tsar, exposing the Tsarist government's control of the press and had been arrested and even exiled on numerous occasions. He supported liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. He was a personal friend of Lenin since 1902, and was acquainted with many revolutionaries. His reputation grew as a literary voice of Russia's bottom strata of society and a fervent advocate of social, political and cultural transportation. Gorky also had a passionate love of the theater. One of his aspirations since the 1890s was to develop a network of provincial theaters for the peasants in hopes to reform Russia's theatrical world. In 1904, he was able to open a theater in his hometown of Nizhny Novgorod, but unfortunately, the government censors banned every play that he proposed and Gorky abandoned the project. On December 31, 1913, after the Romanov Tercentenary, Gorky was allowed to return home to Russia after eight years of living in exile in Italy. By March 1914, he was living in St. Petersburg working as an editor for the underground Bolshevik Zvezda and Pravda newspapers. After the concert, Burenin introduced Coretti to Gorky, who confessed to her that despite his disdain for female entertainers, he was her biggest fan, expressing that her Negro folk songs captured the essence of the struggles of the proletariat. Gorky and Coretti became close friends, and she may have been a frequent guest at his Petrograd apartment on 23 Kronversky Avenue where there was constant drinking, dancing, gambling and frequent readings of 18th Century pornographic novels (Marquis de Sade was rather popular). During these nights at Gorky's home, Coretti would've mingled with publishers, academics, revolutionaries, the great singer Fyodor Chaliapin and even Lenin himself.

Ukraine (1917–1921)

In March 1917, during the February Revolution, Coretti's studies were suddenly interrupted and she pondered at the idea of returning to America. The war and revolution had abruptly ended Russia's importance on the continental theatrical circuit. Extensive touring became difficult and many establishments began shutting down. The vast majority of the African-American community in Russia were rushing to Petrograd's American Embassy and Moscow's Consulate to apply for passports in order to sail across the Black Sea towards Turkey and Romania or board Trans-Siberian trains towards Manchuria and Japan in their journey back to America. However, letters she received from friends such as Ollie Burgoyne and Ida Forcyne who had returned home to America, she was able to learn about the changes in the American entertainment scene. The majority of Black establishments only wanted light-skinned Negro women, Harlem cabarets had women perform shake dances in between the tables and mingle with the audiences as Jazz wailed in the background. Such activities didn't happen in Russian cabarets and music halls. Most of the successful Negro performers returning to America from Europe found themselves suddenly penniless and turning to domestic work.

During the Revolution, Boris relocated south to the Ukraine and accepted a teaching position at Kharkov's new musical conservatory. Soon Coretti followed after him shortly afterwards. Six months later, in September 1917, after years of courtship and refusing his previous four marriage proposals, Coretti and Boris had finally married. She had been reluctant to follow through with the marriage, as she had aspirations of opening a children's vocal school in America. However, Boris informed her of the United States' widespread fear of Bolshevism, anarchism and communism. American newspapers were frequently reporting about mass trials and arrests, also Boris reminded her of how difficult it would be for a Negro woman to open a major establishment in the United States. Coretti also told him of how her first marriage fell apart, yet Boris promised that not all men were the same. He wouldn't allow anyone to interfere with their private lives and reminded her that he loved her no matter what color her skin was, that the human soul didn't depend on skin color. Fortunately, his family and friends quickly accepted his new wife.

From 1917-1921, Coretti performed at Kharkov's Grotezk Cabaret (17 Ekaterinoslavskaya), Theater of Assembled Clerks and the at the Kommerchesky Garden Club (21 Rymarskaya) with Mikhail Bichter's Philharmonic Society Orchestra. She also performed at private parties, particularly at 66 Chernyshevskiy Prospekt, where architect Vladimir Pokrovsky often organized musical evenings in his apartment. After singing a few songs, she'd mingle amongst the other musicians and listen in on the disputes over the development of the Ukrainian artistic scene. She was soon acquainted with artists R.M. Savin, M.A. Sharonov, architect M.F. Pokorny, cellist E. Belousov and composer K.K. Gorsky. As the Russian Civil War raged, from late 1919 until 1920, Coretti and Boris also toured together with the "Concert Brigade of the South-Western Front", that organized musical performances in theatres, libraries, nightclubs, mines, factories, hospitals and Red Army military camps across the Ukraine.

Soviet career and the introduction of jazz (1921–1931)

In late-1921, with the Great Famine raging across the USSR, the couple moved to the Soviet capital, Moscow. The couple resided at Poluektov Pereulok 7, where they shared a communal kitchen with the Duchenne family. The family, especially seven-year-old Igor, enjoyed hearing Coretti's voice ring throughout the apartment. Often Coretti would babysit young Igor Duchenne, who would bring her books from the Library of the USSR Academy of Sciences despite her inability to read in Russian. So instead, she'd cradle him in her arms and rock him to sleep singing, "Sleep my Boy" ("Spi, moy mal'chik" - I. Dunaevsky & Lebedev-Kumach). Unable to tour as the famine spread, from 1921-1923, Coretti decided to continue her studies at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory's Opera Studio, which was under the direction of Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov. She spent her days studying under Varvara Mikhailovna Zarudna and Nadezhda Ignatyevna Kalnin-Gandolfi. Late-1923, shortly after graduation, Ippolitov-Ivanov's Opera Studio staged a remarkable production of Verdi's "Aida", with Coretti performing the lead role. The audience felt her role echoed Coretti's own reality – an Egyptian captive, a Negro slave, who threw off the shackles of slavery in the name of love.

On April 3, 1924, Coretti debuted at Moscow's infamous Bolshoi Theater opening with a remarkable three-day engagement, performing several arias followed by numerous classical numbers written by famous Russian composers.[5] The second half of the program primarily consisted of Negro Spirituals performed in her dramatic lyrical soprano voice. This major performance, her first in Russia since before the revolutions, was met with great enthusiasm and numerous standing ovations. With this success, she hoped to continue performing as an operatic singer, but unfortunately Russian music critics felt she was better suited as a concert artist. After her final performance at the Bolshoi, she departed for Leningrad with a contract for two concerts and a string of engagements across the provinces. In November, returning home from an appearance in the Ukraine, she was writing extensively to W.E.B. du Bois, who had heard of her triumph at the Bolshoi and expressed his plans for a visit to the USSR. Coretti asked du Bois to send her sheet music of popular American music which was difficult to acquire in the Soviet Union and also put him in contact with her mother to cover the costs as she was unable to send money from Moscow.

In April 1925, the couple were performing in Tver, near the village of Vysh-Gorodishche, where Boris was born and where the old Titz estate sat crumbling since the revolution. In October, Coretti and pianist E. Lutsky signed a 20-concert contract with the State Philharmonic Orchestra for across the Northern Caucasus and the Ukraine with a program consisting of Russian composers such as Spendiarov, Vasilenko, Glazunov, Gnesin and also including compositions from Afro-American composers such as Barley, Cook and others. This was the first of her many extensive tours across the Soviet Union under the State Philharmonic Society. Opening on December 7 in Rostov-on-Don, the group traversed across Melitopol, Krasnodar, Simferopol and Yevpatoria. Letters home to friends, Coretti mentioned how much she loved traveling to the sea, although during her engagement in Evpatoria she complained about the city's stuffiness and how impossible it was to find anything suitable to drink. She also mentions her distress with working with the Philharmonic orchestra as she felt wasn't benefitting from her performances and felt they didn't appreciate her talents as a concert artist.

In late-February 1926, Frank Withers (né Frank Douglas Withers; 1880–1952), and his Jazz Kings band (featuring Sidney Bechet) arrived in Moscow, where they received a whirlwind of success upon opening at the Cinema Malaya Dimitrova. Known as the 'Palace of the Silver Screen', the popular cinema opened new Hollywood films there each week to packed audiences and when the Jazz Kings opened there on February 22, the cinema was packed before the first note sounded and couples took to the aisles to dance the Charleston. When Coretti and the Philharmonic Orchestra returned from their Ukrainian tour, the Jazz Kings were making appearances at the Hall of Writers and the Moscow Conservatory. The Philharmonic Orchestra quickly organized a month-long Ukrainian tour for the Jazz Kings, with Coretti as their lead performer, giving her the opportunity to reap from the success jazz was creating in the Soviet Union. In May, the group played a week in Kharkov, two successful weeks in Kiev and a final week in Odessa at the Letnem Theatre, before the Jazz Kings returned to Germany. In July, Coretti was engaged in Leningrad for a week at the Recreation Gardens before returning to the Ukraine in September for an engagement in Ekaterinoslav. The year ended rather interestingly, as she was appearing in a Jewish Music Concert held at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory's Small Hall, where she demonstrated her skill performing traditional songs in the Yiddish language.

During the summer of 1927, Coretti debuted in July onstage in the city of Baku,[6] where she was advertised as the woman who introduced jazz to Azerbaijan despite newspapers not indicating any jazz numbers in her repertoire during her appearance there, although she did perform a number in the Azeri language. On December 11, in the famous Grand Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic, Coretti accompanied the 'First Concert Jazz Band' led by Leopold Teplitsky and composed of about 15 people (2 violins, banjo, grand piano, tuba, trumpets, clarinets, saxophones, trombones and, of course, a great set of percussion instruments). Coretti, quite tall, lush, in an open green silk dress with a pelerine, perfectly in harmony with her golden brown skin, sang in English with a strong, rather low voice of a very beautiful timbre. The concert was unusual for that time. The hall was literally bursting with the public, barely getting the entrance tickets, standing all the time in the gallery, walking along the perimeter of the hall.

From 1928–1931, after recording several songs in Moscow, Coretti began an extensive Soviet tour, appearing in the Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Georgia and deep in Siberia. Although she occasionally performed jazz, she usually reverted to performing Russian Romances or Negro spirituals. On January 29, 1929, she began the year performing at the Karl Marx Club in Minsk, just beside the border leading outside the Soviet Union towards Poland. Four months later, after a lengthy tour across the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic and other Central Asian countries, she returned west to the Ukraine, appearing in Vinnytsia on May 7. Early July, Coretti and Boris received permission to depart the Soviet Union for a four-month Latvian tour. She was set to perform in the Latvian resort town of Jūrmala, 18 years since her last engagement there. The town had become a popular tourist destination for Soviet officials and top union members. In the Edinburgh neighborhood posters and newspapers advertised Coretti's debut at the Sommertheater on July 11, where she performed alongside Georgs Vlašeks and his Orpheans Orchestra for the Edinburgh Sea Festival for a successful week. The following month, on August 12, Coretti and Boris appeared on stage together at Riga's Palladium Kino where she performed beautiful Italian arias, several German and Russian folk songs and ending the program with her Negro folk songs (which consisted of Negro spirituals, Jazz and Blues). She also made subsequent evening appearances on Radio Latvia reaching other parts of the small country. After a month of unreported activity, Coretti resumed her tour, appearing in the seaside towns of Jelgava and Windau (now Ventspils) before returning home to Moscow early November for an engagement at the Polytechnic Museum.

From June 1930-February 1931, she appeared across the Ukraine, Russia's Volga regions and crossed the Ural mountains into Siberia for 9 months. In December 1930, Coretti was in Leningrad, performing in a Jazz revue, "Big Night of the Negro" with Simon Kagan's Orchestra. It was her last Jazz performance as the genre of music had been banned by the Soviet government two months earlier.

Soviet actress and recording artist (1932-1938)

Early 1932, the Titz household had relocated to 15, Savelevski Pereulok, where they inhabited apartment #11, two small dingy rooms on the third floor in Moscow's Western section near Kropotkinskaya Square. During this time, Coretti recorded several songs with the Muztrest Label, including the spirituals, "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "Little David Play on Your Harp". On June 26, Emma Harris, Coretti Arle Titz, actor Bob Ross and engineer Robert Robinson gathered at Nikolayevsky Station to welcome twenty two Afro-American artists (including Langston Hughes)[7] that were invited the Soviet Union to produce a film depicting Negro laborers in their difficult working conditions in the American South. The film was based on Vladimir Mayakovsky's 1925 poem, "Black & White", which protested American racism and imperialism. The film was sponsored by the Comintern and was to be produced by the Russo-German film company Meschrabpom.

In February 1933, Coretti debuted for the first time in Armenia. Her performance at Yerevan's House of Culture was extremely well received by the press, especially for her stellar performance of Armenian folk songs.

On March 29, 1934, Coretti celebrated her tenth year on the Soviet stage with a radio concert at the Moscow Radio-Theater with many other Soviet entertainers.[8] The radio broadcast reached as far as France and Norway. Throughout the year, she performed on Moscow's Radio-Komintern. After the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, Stalin's assumed successor, on December 1, 1934, life became much more oppressed within the Soviet Union. On December 20, Coretti and Afro-American expat singer Celeste Cole welcomed Paul Robeson at the White Russia Train Station for his first Soviet Tour. The following month, on January 14, 1935, Coretti performed at a benefit gala held for Robeson at the House of the Kino. Unfortunately, she wasn't particularly fond of Robeson and avoided him whenever possible.

From February–March 1935, after recording more songs with the April Recording Label, she toured the Ukraine's Donbass region and Russia's newly created Chelyabinsk Oblast (Chelyabinsk and Magnitogorsk) before traveling to Moscow's Mosfilm Studios to appear as Marion Dixon's (Lyubov Orlova) maid in Grigori Aleksandrov's latest melodramatic comedy film, "Circus". However, Coretti's uncredited appearance is only for 30 seconds (40:33–41:03 and 41:27–41:31 mark). During this time, Coretti developed a close friendship with Marian Anderson. In Late-1935, she appeared in Kazakhstan's capital Alma-Ata (now Almaty).

The majority of 1936 was spent performing at Moscow's Tchaikovsky Conservatory and on Radio-Moscow, except for a brief appearance at the Summer Theater in Kursk. From 1937–1938, Coretti resumed touring, appearing in Penza,[9] Vologda, Arkhangelsk, Odessa, Vladivostok, Solikamsk, Astrakhan and around the Sverdlovsk Oblast.

The Great Patriotic War and later career (1939–1951)

After the outbreak of World War II, late 1939–1940, Coretti began another Soviet tour for over 14 months across Siberia and the Far East.

From October–December 1941, after the German invasion of the USSR, Coretti's touring halted and she volunteered as a nurse for Moscow's Military Hospital No.5012 (now N.I. Pirogova Hospital). On December 5, the Red Army brought all its might into German positions causing the Wehrmacht to hastily withdraw. This marked the prelude to many victories for the Red Army. Despite the war, on December 7, at the Maly Theatre, the All-Union Tour Association organized a concert revue of English and American Music & Songs. Honored Artist of the USSR, F. Petrova sang "Cowboy from Texas" and "Matrosskaya". This was followed by Coretti's successful performance, introducing Muscovites to the vocal works of English composers Purcell, Balfi, Quelter and American composers Johnson and Lawrence.For the remainder of December, Boris and Coretti toured the Ivanovo Oblast.

Early 1942, the couple continued touring, appearing in the Gorky Oblast, Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and Kirov Oblast until Boris resumed teaching in Moscow. From 1943-1945, Coretti continued touring military bases and hospitals with the Soviet Philharmonic Orchestra, especially in Arkhangelsk, Novosibirsk and Murmansk.

She returned to Moscow in May 1945, to appear in Vasily M. Zhuravlev's Fifteen-Year-Old Captain, which began filming at Gorky Soyuzdetfilm Studios. Mikhail Astangov, Osip Abdulov, Alexander Khvylya, Pavel Sukhanov, Vsevolod Larionov, Elena Izmaylova, Sergey Tsenin, Viktor Kulakov, Ivan Bobrov, Weyland Rudd and Coretti were all honored artists, and despite the small budget and the majority of the actors being constantly preoccupied with other engagements, the film was predicted to be the biggest hit of the year. Shooting resumed in mid-May shortly after Victory Day, where the first scenes were between Coretti and the six-year-old Azarik Messerer. Under the blinding lights, young Azarik drifted asleep underneath a heavy blanket while Coretti, in the role of the black nanny named Nan, sang a Russian lullaby. To the entire film crew, Coretti was treated like a prima donna, even the director was afraid to approach her. Despite being seen throughout the film in the background, she only had one speaking scene. On June 6, in-between filming, Boris and Coretti were decorated with the Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945". On July 14, the cast traveled to Georgia to film the African scenes on the Black Sea coast for seven months. Two-thirds of the film was shot on Primorsky Boulevard in Batumi and in the vicinity of the city, Tsihis-Dziri and Adzharis-Tskhali. On the beach was built the African village "Kazonde as on screen, Transcaucasia's nature created a complete illusion of African nature. While in Batumi, since her only scene was already shot, Coretti preoccupied her time with Azarik, improving his poor table manners and teaching him how to properly hold a knife and fork. After ten months of filming 15 kilometres of film, the "Fifteen Year Old Captain was finally released on March 18, 1946, immediately conquering the hearts of children and adults across the Soviet Union.

In 1947, after forty years of intense and continuous work, the forces of Arle-Titz were undermined, newspapers reported that her voice became worn out and lost its former beauty and full-soundness. Although it may have been that the Soviet Union's music industry finally decided to shelf its once-popular black prima donna. Which explains why after the war, she was no longer mentioned in Soviet news, as she was living quietly in Moscow until her death in 1951. After the death and cremation of Coretti Henrichovna Arle-Titz on December 14, 1951, Boris Borisovich turned to Varvara Mikhailovna Zarudnaya's niece, Vera Nikolaevna, with a request for the temporary burial of the urn with the ashes of his wife next to her close friend, composer Ippolitov-Ivanov. Coretti Arle-Titz was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery on December 15, 1951, in the family grave of Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov and his wife, Varvara Mikhailovna Zarudnaya. In later years, Boris Borisovich did not have time to rebury the remains of Coretti, and after his death (in 1963) he was instead buried beside her.

References

- Opportunity. National Urban League. 1932.

- "Simon Geza Gabor. The Pre-History of Jazz in Hungary". Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1936). The Crisis. Crisis Publishing Company. pp. 1–.

- William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1936). The Crisis. Crisis. pp. 1–.

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (September 4, 1936). "The Crisis". Crisis. p. 204. Retrieved September 4, 2020 – via Google Books.

- "Jazz History". Bakujazzfestival. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- The Collected Works of Langston Hughes — University of Missouri Press, 2001. — P. 69.

- Bois, William Edward Burghardt Du (September 4, 1936). "The Crisis". Crisis Publishing Company. p. 204. Retrieved September 4, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Bois, William Edward Burghardt Du (September 4, 1936). "The Crisis". Crisis Publishing Company. p. 204. Retrieved September 4, 2020 – via Google Books.