Vladivostok

Vladivostok (Russian: Владивосто́к, IPA: [vlədʲɪvɐˈstok] (![]() listen)) is the largest city and the administrative centre of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area of 331.16 square kilometres (127.86 square miles), with a population of 606,561 residents,[11] up to 812,319 residents in the urban agglomeration. Vladivostok is the second-largest city in the Far Eastern Federal District, as well as the Russian Far East, after Khabarovsk.

listen)) is the largest city and the administrative centre of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area of 331.16 square kilometres (127.86 square miles), with a population of 606,561 residents,[11] up to 812,319 residents in the urban agglomeration. Vladivostok is the second-largest city in the Far Eastern Federal District, as well as the Russian Far East, after Khabarovsk.

Vladivostok

Владивосток | |

|---|---|

City[1] | |

.jpg.webp)   .jpg.webp)  .jpg.webp) Top-down, left-to-right: View of Zolotoy Bridge and the Golden Horn Bay at night, with the Russky Bridge in the distance; GUM Department Store; Arseniev State Museum of Primorsky Region; The campus of Far Eastern Federal University; Vladivostok Railway Station; and Central Square | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

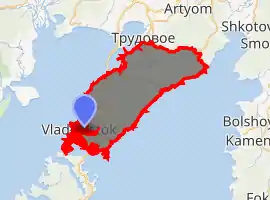

Location of Vladivostok

| |

Vladivostok Location of Vladivostok  Vladivostok Vladivostok (Russia)  Vladivostok Vladivostok (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 43°08′N 131°54′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Primorsky Krai[1] |

| Founded | 2 July 1860[2] |

| City status since | 22 April 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma |

| • Head | Oleg Gumenyuk[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 331.16 km2 (127.86 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018)[5] | 604,901 |

| • Rank | 22nd in 2010 |

| • Subordinated to | Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Capital of | Primorsky Krai[6], Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| • Capital of | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| Time zone | UTC+10 (MSK+7 |

| Postal code(s)[9] | 690xxx |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 423[10] |

| OKTMO ID | 05701000001 |

| City Day | First Sunday of July |

| Website | www |

The city was founded in 1860 as a Russian military outpost after the Treaty of Aigun and the Convention of Peking with the Qing dynasty. In 1872, the main Russian naval base on the Pacific Ocean was transferred to the city, and thereafter Vladivostok began to grow. After the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Vladivostok was occupied in 1918 by foreign troops, the last of whom were not withdrawn until 1922, by that time the anti-revolutionary White Army forces in Vladivostok promptly collapsed, and Soviet power was established in the city. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Vladivostok became the administrative centre of Primorsky Krai.

Vladivostok is the largest Russian port on the Pacific Ocean, and the chief economic, scientific and cultural centre of the Russian Far East, as well as an important tourism centre in Russia. As the terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the city was visited by over 3 million tourists in 2017.[12] The city is the administrative centre of the Far Eastern Federal District, and is the home to the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet of the Russian Navy. For its unique geographical location, and its European culture, the city is called "Europe in Asia".[13][14] Many foreign consulates and businesses have offices in Vladivostok. In a Russian context, the city is remote enough to be geographically closer to northern Australia than it is to Moscow.[15][16] With an annual mean temperature of around 5 °C (41 °F) Vladivostok has a cold climate for its mid-latitude coastal setting. This is due to winds from the vast Eurasian landmass in winter, also cooling the ocean temperatures.

Names and etymology

Vladivostok means 'Lord of the East' or 'Ruler of the East'. The name derives from Slavic владь (vlad, 'to rule') and Russian восток (vostok, 'east'); see the etymology of Vladimir (name).

It was first named in 1859 along with other features in the Peter the Great Gulf area by Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky. The name was first applied to the bay but, following an expedition by Alexey Shefner in 1860, was later applied to the new settlement.[17]

On Chinese maps from the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), Vladivostok is called Yongmingcheng (永明城; Yǒngmíngchéng). Since the Qing dynasty, the city is known as Haishenwai (海參崴; Hǎishēnwǎi) in Chinese, from the Manchu Haišenwai (Manchu: ᡥᠠᡳᡧᡝᠨᠸᡝᡳ; Möllendorff: Haišenwai; Abkai: Haixenwai) or 'small seaside village'.[18]

In China, Vladivostok is now officially known by the transliteration 符拉迪沃斯托克 (Fúlādíwòsītuōkè), although the historical Chinese name 海参崴 (Hǎishēnwǎi) is still often used in common parlance and outside Mainland China to refer to the city.[19][20] According to the provisions of the Chinese government, all maps published in China have to bracket the city's Chinese name.[21]

The modern-day Japanese name of the city is transliterated as Urajiosutoku (ウラジオストク). Historically, the city's name was transliterated with Kanji as 浦塩斯徳 and shortened to Urajio (ウラジオ, 浦塩).[22]

History

Foundation

For a long time, the Russian government was looking for a stronghold in the Far East; this role was played in turn by the settlements of Okhotsk, Ayan, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, and Nikolaevsk-on-Amur. By the middle of the 19th century, the search for the outpost had reached a dead end: none of the ports met the necessary requirement: to have a convenient and protected harbor, next to trade routes.[23] The Aigun Treaty was concluded by the forces of the Governor-General of Eastern Siberia Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, an active exploration of the Amur region began, and later, as a result of the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin and the Convention of Peking, the territory of modern Vladivostok were annexed to Russia. The very name Vladivostok appeared in the middle of 1859, was used in newspaper articles and denoted a bay.[23] On June 20, (July 2) 1860 the transport of the Siberian Military Flotilla "Mandzhur" under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Alexei Karlovich Shefner delivered a military unit to the Golden Horn Bay to establish a military post, which has now officially received the name of Vladivostok.[24]

“ The port can be considered the best of all. He reminds many of Olga, but only less of her, more comfortable, but warmer and more fun. However, the same oaks all around, the same picturesque mountains. In the lowlands, rivers murmur; there are many springs on the banks. Our post, set up the other day, with its white tents, looks good in a group of oak trees that have not yet been cut down and have just cleared. ”

19th century - early 20th century

On October 31, 1861, the first civilian settler, a merchant, Yakov Lazarevich Semyonov, arrived in Vladivostok with his family. On March 15, 1862, the first act of his purchase of land was registered, and in 1870 Semyonov was elected the first head of the post, and a local self-government emerged.[23] By this time, a special commission decided to designate Vladivostok as the main port of the Russian Empire in the Far East.[26] In 1871, the main naval base of the Siberian Military Flotilla, the headquarters of the military governor and other naval departments were transferred from Nikolaevsk-on-Amur to Vladivostok.[27]

In the 1870s, the government encouraged resettlement to the South Ussuri region, which contributed to an increase in the population of the post: according to the first census of 1878, there were 4,163 inhabitants. The city status was adopted and the city Duma was established, the post of the city head, the coat of arms was adopted, although Vladivostok was not officially recognized as a city.[27]

Due to the constant threat of attack from the Royal Navy, Vladivostok also actively developed as a naval base.

In 1880, the post officially received the status of a city. The 1890s saw a demographic and economic boom associated with the completion of the construction of the Ussuriyskaya branch of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Chinese-Eastern Railway.[27] According to the first census of the population of Russia on February 9, 1897 roughly 29,000 inhabitants lived in Vladivostok, and ten years later the city's population tripled.[27]

The first decade of the 20th century was characterized by a protracted crisis caused by the political situation: the government's attention was shifted to Port Arthur and the Port of Dalny. As well as the boxing uprising in North China in 1900–1901, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, and finally the first Russian revolution led to stagnation in the economic activity of Vladivostok.[28]

Since 1907, a new stage in the development of the city began: the loss of Port Arthur and Dalny again made Vladivostok the main port of Russia on the Pacific Ocean. A free port regime was introduced, and until 1914 the city experienced rapid growth, becoming an important economic centre in the Asia-Pacific, as well as an ethnically diverse city with a population exceeding over 100,000 inhabitants: during the time ethnic Russians made up less than half of the population,[28] and large Asian communities developed in the city. The public life of the city flourished; many public associations were created, from charities to hobby groups.[29]

World War I, Revolution and Occupation

During World War I, no active hostilities took place in the city.[30] However, Vladivostok was an important staging post for the import of military-technical equipment for troops from allied and neutral countries, as well as raw materials and equipment for industry.[31]

Immediately after the October Revolution in 1917, during which the Bolsheviks came to power, the Decree on Peace was announced, and as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk concluded between the Bolshevik government of Russia and the Central Powers, led to the end of Soviet Russia's participation from World War I. On October 30, the sailors of the Siberian Military Flotilla decided to "rally around the united power of the Soviets", and the power of Vladivostok, as well as all of the Trans-Siberian Railway passed to the Bolsheviks.[30] During the Russian Civil War, from May 1918,[32] they lost control of the city to the White Army-allied Czechoslovak Legion, who declared the city to be an Allied protectorate. Vladivostok became the staging point for the Allies' Siberian intervention, a multi-national force including Japan, the United States, and China; China sent forces to protect the local Chinese community after appeals from Chinese merchants.[33] The intervention ended in the wake of the collapse of the White Army and regime in 1919; all Allied forces except the Japanese withdrew by the end of 1920.[30]

Throughout 1919 the region was engulfed in a partisan war.[30] To avoid a war with Japan, with the filing of the Soviet leadership, the Far Eastern Republic, a Soviet-backed buffer state between the Soviet Russia and Japan, was proclaimed on April 6, 1920. The Soviet government officially recognized the new republic in May, but in Primorye a riot occurred, where significant forces of the White Movement were located, leading to the creation of the Provisional Priamurye Government, with Vladivostok as its capital.[34]

In October 1922, the troops of the Red Army of the Far Eastern Republic under the command of Ieronim Uborevich occupied Vladivostok, displacing the White Army formations from it. In November, the Far Eastern Republic liquidated, and became a part of Soviet Russia.[27]

Soviet period

By the time of the establishment of Soviet power, Vladivostok was in decline: the retreating forces of the Japanese army removed all material values from the city. Life was paralyzed: there was no money in the banks, the equipment of enterprises was plundered. Due to mass emigration and repression, the city's population decreased to 106,000 inhabitants.[31] During 1923 to 1925, the government adopted a plan of the "three-year restoration", during which the commercial port was resumed, which became the most profitable in the country in 1924 to 1925.[31][35] The recovery period was distinguished by its peculiarities: the Russian Far East did not find war communism, but immediately fell into the situation of the New Economic Policy.[35]

In 1925, the government decides to accelerate the industrialization of the country. The first five-year plans changed the face of Primorye, making it an industrial region, partly as a result of the creation of numerous concentration camps in the region.[35] In the 1930s-1940s, Vladivostok served as a transit point on the route of delivering prisoners and cargo for the Sevvostlag of the Soviet super-trust Dalstroy. The notorious Vladivostok transit camp was located in the city. In addition, in the late 1930s-early 1940s, the Vladivostok forced labor camp (Vladlag) was located in the area of Vtoraya Rechka railway station.[36]

Vladivostok was not a place of hostilities during the Great Patriotic War, although there was a constant threat of attack from Japan. In the city, the first in the country, the "Defense Fund" was created, to which the residents of Vladivostok carried personal values.[37] During the war years Vladivostok handled imported cargo (lend-lease) almost four times more than Murmansk and almost five times more than Arkhangelsk.[38]

By the decree of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union "Issues of the Fifth Navy" dated August 11, 1951, a special regime was introduced in Vladivostok (it began to operate on January 1, 1952); the city becomes closed to foreigners.[39] It was planned to remove from Vladivostok not only foreign consulates, but also the merchant and fish fleet and transfer all regional authorities to Voroshilov (now Ussuriysk). However, these plans were not implemented.[39]

During the years of the Khrushchev Thaw, Vladivostok received special attention from state authorities. For the first time, Nikita Khrushchev visited the city in 1954 to finally decide whether to secure the status of a closed naval base for him.[40] It was noted that at that time the urban infrastructure was in a deplorable state.[40] In 1959, Khrushchev visited the city again. The result is a decision on the accelerated development of the city, which was formalized by the decree of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union on January 18, 1960.[40] During the 1960s, a new tram line was built, a trolleybus was launched, the city became a huge construction site: residential neighborhoods were being erected on the outskirts, and new buildings for public and civil purposes were erected in the center.[40]

In 1974, Gerald Ford paid an official visit to Vladivostok, to meet with Leonid Brezhnev, becoming the first President of the United States to visit the Soviet Union. Both sides signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which helped to contain the nuclear arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War.[41]

On September 20, 1991, Boris Yeltsin signed decree No. 123 "On the opening of Vladivostok for visiting by foreign citizens", which entered into force on January 1, 1992, ceasing Vladivostok to be a closed city.[42]

Modern period

In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th APEC summit. Leaders from the APEC member countries met at Russky Island, off the coast of Vladivostok.[43] With the summit on Russky Island, the government and private businesses inaugurated resorts, dinner and entertainment facilities, in addition to the renovation and upgrading of Vladivostok International Airport.[44] Two giant cable-stayed bridges were built in preparation for the summit, the Zolotoy Rog bridge over the Zolotoy Rog Bay in the center of the city, and the Russky Island Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island (the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world). The new campus of Far Eastern Federal University was completed on Russky Island in 2012.[45]

Geography

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 kilometers (19 mi) long and 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) wide.

The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, 257 meters (843 ft). Eagle's Nest Hill is often called the highest point of the city; but, with a height of only 199 meters (653 ft), or 214 meters (702 ft) according to other sources, it is the highest point of the downtown area, but not of the whole city.

Located in the extreme southeast of the Russian Far East, in the extreme southeast of North Asia. Vladivostok is geographically closer to Anchorage, Alaska and even Darwin, Australia than it is to the nation's capital of Moscow. Vladivostok is also closer to Honolulu, Hawaii than to the city of Sochi in Southern Russia. It also is further east than any area south of it in China and the entire Korean peninsula.

Climate

Vladivostok has a monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dwb) with warm, humid and rainy summers and cold, dry winters. Owing to the influence of the Siberian High, winters are far colder than a latitude of 43 °N should warrant given its low elevation and coastal location, with a January average of −12.3 °C (9.9 °F). Since the maritime influence is strong in summer, Vladivostok has a relatively cold annual climate for its latitude. Vladivostok's yearly mean of around 5 °C (41 °F) is some ten degrees lower than in cities on the French Riviera on a similar coastal latitude on the other side of Eurasia. Winters in particular are around 20 °C (36 °F) colder than on the mildest coastlines this far north, and are considerably colder than locations on the North American east coast at similar latitudes such as Halifax, Nova Scotia and Portland, Maine.

In winter, temperatures can drop below −20 °C (−4 °F) while mild spells of weather can raise daytime temperatures above freezing. The average monthly precipitation, mainly in the form of snow, is around 18.5 millimeters (0.73 in) from December to March. Snow is common during winter, but individual snowfalls are light, with a maximum snow depth of only 5 centimeters (2.0 in) in January. During winter, clear sunny days are common.

Summers are warm, humid and rainy, due to the East Asian monsoon. The warmest month is August, with an average temperature of +19.8 °C (67.6 °F). Vladivostok receives most of its precipitation during the summer months, and most summer days see some rainfall. Cloudy days are fairly common and because of the frequent rainfall, humidity is high, on average about 90% from June to August.

On average, Vladivostok receives 840 millimeters (33 in) per year, but the driest year was 1943, when 418 millimeters (16.5 in) of precipitation fell, and the wettest was 1974, with 1,272 millimeters (50.1 in) of precipitation. The winter months from December to March are dry, and in some years they have seen no measurable precipitation at all. Extremes range from −31.4 °C (−24.5 °F) in January 1931 to +33.6 °C (92.5 °F) in July 1939.[46]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −12.3 (9.9) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −15.4 (4.3) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.4 (−24.5) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−31.4 (−24.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14 (0.6) |

15 (0.6) |

27 (1.1) |

48 (1.9) |

81 (3.2) |

110 (4.3) |

164 (6.5) |

156 (6.1) |

117 (4.6) |

57 (2.2) |

28 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

833 (32.8) |

| Average rainy days | 0.3 | 0.3 | 4 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 14 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 133 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 47 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 58 | 57 | 60 | 67 | 76 | 87 | 92 | 87 | 77 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 178 | 184 | 216 | 192 | 199 | 130 | 122 | 149 | 197 | 205 | 168 | 156 | 2,096 |

| Source 1: Погода и Климат[47] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[48] | |||||||||||||

| Sea temperature data for Vladivostok | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | -1.2 (29.8) |

-1.6 (29.1) |

-0.9 (30.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.64 (47.6) |

| Source: [49] | |||||||||||||

Politics

The structure of the city administration has the City Council at the top.

The responsibilities of the administration of Vladivostok are:

- Exercise of the powers to address local issues of Vladivostok in accordance with federal laws, normative legal acts of the Duma of Vladivostok, decrees and orders of the head of the city of Vladivostok;

- The development and organization of the concepts, plans and programs for the development of the city, approved by the Duma of Vladivostok;

- Development of the draft budget of the city;

- Ensuring implementation of the budget;

- The use of territory and infrastructure of the city;

- Possession, use and disposal of municipal property in the manner specified by decision of the Duma of Vladivostok

Legislative authority is vested in the City Council. The new City Council began operations in 2001 and in June that year, deputies of the Duma of the first convocation of Vladivostok began their work. On 17 December 2007, the Duma of the third convocation began. The deputies consist of 35 elected members, including 18 members chosen by a single constituency, and 17 deputies from single-seat constituencies.

Administrative and municipal status

Vladivostok is the administrative centre of the krai. Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is, together with five rural localities, incorporated as Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction is incorporated as Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug.[7]

Administrative divisions

Vladivostok is divided into five administrative districts:

- Leninsky

- Pervomaisky

- Pervorechensky

- Sovietsky

- Frunzensky

Local government

The city charter approved the following structure of local government bodies:[50]

- City Duma is a representative body

- The head of the city is the highest official

- Administration - executive and administrative body

- Chamber of Control and Accounts - control body

The history of the Vladivostok City Duma dates back to November 21, 1875, when 30 "vowels" were elected. Great changes took place in it after the 1917 Revolution, when the first general elections were held and women were allowed to vote. The last meeting of the Vladivostok City Duma took place on October 19, 1922, and on October 27 it was officially abolished. In Soviet times, its functions were performed by the City Council. In 1993, by a presidential decree, the Soviets were dissolved and until 2001 all attempts to elect a new Duma were unsuccessful. The Duma of the city of Vladivostok of the 5th (current) convocation began work in the fall of 2017, consisting of 35 deputies.[51]

The head of the city of Vladivostok, on the principles of one-man management, manages the administration of the city of Vladivostok, which he forms in accordance with federal laws, the laws of the Primorsky Territory and the charter of the city. The structure of the city administration is approved by the City Duma on the proposal of the head. The structure of the administration of the city of Vladivostok may include sectoral (functional) and territorial bodies of the administration of the city of Vladivostok.[52]

The mayor of the city from May 2008 to June 2016 was Igor Pushkaryov, who previously held the position of a member of the Federation Council from Primorsky Krai. Since June 27, 2016, the first deputy mayor, Konstantin Loboda, has been appointed as the new acting mayor of Vladivostok.[53] On December 21, 2017, Vitaly Vasilyevich Verkeenko was appointed the head of the city.

Demographics

Population, dynamics, age and sex structure

.jpg.webp)

According to the Russian Census of 2010, Vladivostok had a population of over 592,000 residents, with over 616,800 residents in the urban agglomeration.[54] According to the Primorsky State Statistics Service for 2016, the total permanent population of the city's urban agglomeration was over 633,167 residents.[55] Since the founding of the city, its population has been actively growing almost all the time, except for the periods of the Russian Civil War and the demographic crisis after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s. In the 1970s, the population exceeded over 500,000 residents, and in 1992 it reached a historical maximum exceeding over 648,000 residents. The average population density is 1831.9 people/km2.

In recent years, there has been a positive trend towards a gradual increase in the population, both due to migration processes and due to an increase in the birth rate. Over the past five years, the population has increased by 30,000: since 2013, there has been a positive dynamics of natural growth, and at the end of 2015 it amounted to 727 people.[56] In 2020, the population of Vladivostok has reached over 600,000 residents, as reported by the Federal Statistics of Russia.[57]

In the age structure of the city's population, a large proportion of the population is older than the working age, which is explained by the process of demographic aging. The age structure of the population: younger than able-bodied - 12.7%, able-bodied - 66.3%, older than able-bodied - 21%.[54] The population of Vladivostok, like the whole of Russia, is characterized by a significant excess of the number of women over the number of men.[54]

Ethnic composition

According to the Russian Census of 2010, representatives of more than seventy nationalities and ethnic groups live in Vladivostok. Among them, the largest ethnic groups (over a thousand people): are ethnic Russians - 475,200 people, Ukrainians - 10,474 people, Uzbeks - 7,109 people, Koreans - 4,192 people, Chinese - 2,446 people, Tatars - 2,295 people, Belarusians - 1,642 people, Armenians - 1,635 people, and Azerbaijanis - 1,252 people.[58]

According to studies, since 2002, there has been a change in the ethnic composition of the city as a result of migration processes: the share of Uzbeks increased by - 14.4 times, the share of Chinese and Tajiks by - 5.4 times, the share of Kyrgyz - by 8.5 times, and the share of by Koreans - 1.6 times. More than half of the Koreans of the Primorsky Territory live compactly in two cities - Vladivostok and Ussuriysk. More than 80% of Primorye Uzbeks live in Vladivostok. As noted, the share of Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians, Tatars traditionally living in the city has decreased.[59]

Vladivostok is widely considered to be an ethnically diverse city,[60] even though it has an ethnic Russian majority population, it still is one of the only few cities in Russia with a large Asian population. However, it is noted that today Vladivostok does not have the same multinational diversity as in the period from the 19th century to the Great Patriotic War, when entire national quarters existed in it, including the Chinese Millionka, the Korean Slobodka, and the Japanese quarter of Nihonzin Mati. Historical German, French, Estonian, American, and Central Asian diasporas of the beginning of the XXI century have been little studied.[60]

Economy

The city's main industries are shipping, commercial fishing, and the naval base. Fishing accounts for almost four-fifths of Vladivostok's commercial production. Other food production totals 11%.

A very important employer and a major source of revenue for the city's inhabitants is the import of Japanese cars.[61] Besides salesmen, the industry employs repairmen, fitters, import clerks as well as shipping and railway companies.[62] The Vladivostok dealers sell 250,000 cars a year, with 200,000 going to other parts of Russia.[62] Every third worker in the Primorsky Krai has some relation to the automobile import business. In recent years, the Russian government has made attempts to improve the country's own car industry. This has included raising tariffs for imported cars, which has put the car import business in Vladivostok in difficulties. To compensate, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin ordered the car manufacturing company Sollers to move one of its factories from Moscow to Vladivostok. The move was completed in 2009, and the factory now employs about 700 locals. It is planned to produce 13,200 cars in Vladivostok in 2010.[61]

Seaport

Vladivostok is a link between the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Pacific Sea routes, making it an important cargo and passenger port. It processes both cabotage and export-import general cargo of a wide range. 20 stevedoring companies operate in the port.[63] The cargo turnover of the Vladivostok port, including the total turnover of all stevedoring companies, at the end of 2018 amounted to 21.2 million tons.[64]

In 2015, the total volume of external trade seaport amounted to more than 11.8 billion dollars.[65] Foreign economic activity was carried out with 104 countries.[65]

Tourism

Vladivostok is located in the extreme southeast of the Russian Far East, and is the closest city to the countries of the Asia-Pacific with an exotic European culture, which makes it attractive to tourists.[66] The city is included in the project for the development of the Far East tourism "Eastern Ring". Within the framework of the project, the Primorsky Stage of the Mariinsky Theatre was opened, and there are plans to open branches of the Hermitage Museum, the Russian Museum, the Tretyakov Gallery and the State Museum of Oriental Art.[67] Vladivostok entered the top ten Russian cities for recreation and tourism according to Forbes, and also took the fourteenth place in the National Tourism Rating.[68]

In addition to being the cultural centre, the city also is the centre of tourism in the Peter the Great Gulf. The city's resort area is located on the coast of Amur Bay, which includes over 11 sanatoriums.[69] Vladivostok also has a bustling gambling zone,[70] which has over 11 casinos planned to open by 2023.[71] Tigre de Cristal, the city's first casino, was visited by over 80,000 tourists, in less than a year of its opening.[72]

In 2017, the city was visited by around 3,000,000 tourists, including 640,000 foreigners, of which over 90% are tourists from Asia, specifically China, South Korea and Japan.[12] Domestic tourism is based on business tourism (business trips to exhibitions, conferences), which accounts for up to 70% of the inbound flow. In Vladivostok, diplomatic tourism is also developed, as there are 18 foreign consulates in the city.[73] There are 46 hotels in the city, with a total fund of 2561 rooms.[73] The vast majority of the travel companies of Primorsky Krai (86%) are concentrated in Vladivostok, and their number was around 233 companies in 2011.[74]

Transportation

The Trans-Siberian Railway was built to connect European Russia with Vladivostok, Russia's most important Pacific Ocean port. Finished in 1905, the rail line ran from Moscow to Vladivostok via several of Russia's main cities. Part of the railroad, known as the Chinese Eastern Line, crossed over into China, passing through Harbin, a major city in Manchuria. Today, Vladivostok serves as the main starting point for the Trans-Siberian portion of the Eurasian Land Bridge.

Vladivostok is the main air hub in the Russian Far East. Vladivostok International Airport (VVO) is the home base of Aurora, a subsidiary of Aeroflot. The airline was formed by Aeroflot in 2013 by amalgamating SAT Airlines and Vladivostok Avia. The Vladivostok International Airport was significantly upgraded in 2013 with a new 3500-metre runway capable of accommodating all aircraft types without any restrictions. The Terminal A was built in 2012 with a capacity of 3.5 million passengers per year.

International flights connect Vladivostok with Japan, China, Philippines, North Korea and South Korea, Vietnam.

It is possible to get to Vladivostok from several of the larger cities in Russia. Regular flights to Seattle, Washington, were available in the 1990s but have been cancelled since. Vladivostok Air was flying to Anchorage, Alaska, from July 2008 to 2013, before its transformation into Aurora airline.

Vladivostok is the starting point of Ussuri Highway (M60) to Khabarovsk, the easternmost part of Trans-Siberian Highway that goes all the way to Moscow and Saint Petersburg via Novosibirsk. The other main highways go east to Nakhodka and south to Khasan.

Urban transportation

On 28 June 1908, Vladivostok's first tram line was started along Svetlanskaya Street, running from the railway station on Lugovaya Street. On 9 October 1912, the first wooden cars manufactured in Belgium entered service. Today, Vladivostok's means of public transportation include trolleybus, bus, tram, train, funicular, and ferryboat. The main urban traffic lines are City Centre—Vtoraya Rechka, City Centre—Pervaya Rechka—3ya Rabochaya—Balyayeva, and City Centre—Lugovaya Street.

Cars of the Vladivostok funicular

Cars of the Vladivostok funicular Buses in Vladivostok

Buses in Vladivostok

In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th Summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. In preparation for the event, the infrastructure of the city was renovated and improved. Two giant cable-stayed bridges were constructed in Vladivostok, namely the Zolotoy Rog Bridge over the Golden Horn Bay in the centre of the city, and the Russky Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island, where the summit took place. The latter bridge is the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world.

Education

There are 114 general education institutions in Vladivostok, with a total number of students of 50,700 people (in 2015). The municipal education system of the city consists of preschool organizations, primary, basic, secondary general education schools, lyceums, gymnasiums, schools with in-depth study of individual subjects, and centers of additional education.

The municipal educational network includes: 2 gymnasiums, 2 lyceums, 13 schools with advanced study of individual subjects, one primary school, 2 basic schools, 58 secondary schools, four evening schools, one boarding school, one boarding school. Three Vladivostok schools are included in the Top-500 schools of the Russian Federation.[75] At the municipal level, there is a city system of school olympiads, a city scholarship has been established for outstanding achievements of students.

In 2016, branches of the Academy of Russian Ballet and the Nakhimov Naval School were opened.[76][77]

Dozens of colleges, schools and universities provide vocational education in Vladivostok. The beginning of higher education was laid in the city with the founding of the Oriental Institute.[78] At the moment, the largest university in Vladivostok is the Far Eastern Federal University. More than 41,000 students study in it, 5,000 employees work, including 1,598 teachers. It accounts for a large share (64%) of scientific publications among Far Eastern universities.[78]

Also, higher education in the city is represented by such local universities:

- Far Eastern Federal University

- Vladivostok State University of Economics and Service

- Vladivostok State Medical University

- Maritime State University

- Far Eastern State Institute of Arts

- Far Eastern State Technical Fisheries University

- Pacific Higher Naval School and Pacific State Medical University

- Branches of the Russian Customs Academy

- The International Institute of Economics and Law

- Far Eastern Law Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia

- Saint Petersburg University of the State Fire Service of the Ministry of Emergencies of Russia

Media

Over fifty newspapers and regional editions to Moscow publications are issued in Vladivostok. The largest newspaper of the Primorsky Krai and the whole Russian Far East is Vladivostok News with a circulation of 124,000 copies at the beginning of 1996. Its founder, joint-stock company Vladivostok-News, also issues a weekly English-language newspaper Vladivostok News. The subjects of the publications issued in these newspapers vary from information about Vladivostok and Primorye, to major international events. Newspaper Zolotoy Rog (Golden Horn) gives every detail of economic news. Entertainment materials and cultural news constitute a larger part of Novosti (News) newspaper which is the most popular among Primorye's young people. Also, new online mass media about the Russian Far East for foreigners is the Far East Times. This source invites readers to take part in informational support of R.F.E. for visitors, travellers and businessmen. Vladivostok operates many online news agencies, such as NewsVL.ru, Primamedia, Primorye24 and Vesti-Primorye. From 2012 to 2017 there operates youth online magazine Vladivostok-3000.

As of 2020, there operate nineteen radio stations, including three 24-hour local stations. Radio VBC (FM 101,7 MHz, since 1993) broadcasts classic and modern rock music, oldies and music of 1980s-1990s. Radio Lemma (FM 102,7 MHz, since 1996) broadcasts news, radioshows and various Russian and European-American songs. Vladivostok FM (FM 106,4 MHz, was launched in 2008) broadcasts local news and popular music (Top 40). The State broadcasting company "Vladivostok" broadcasts local news and music programs from 7 to 9, from 12 to 14 and from 18 to 19 on weekdays on the frequency of Radio Rossii (Radio of Russia).

Culture

Theatres

Maxim Gorky Academic Theatre, named after the Russian author Maxim Gorky, was founded in 1931 and is used for drama, musical and children's theatre performances.

There are five professional theaters in the city. In 2014, they were visited by 369,800 spectators. The Primorsky Regional Academic Drama Theater named after Maxim Gorky is the oldest state theater in Vladivostok, opened on November 3, 1932. The theater employs 202 people: 41 actors (of them - three folk and nine honored artists of Russia).[79]

The Primorsky Pushkin Theater was built in 1907–1908, and is currently one of the main cultural centers of the city. In the 1930s-40s, the following still operating ones were successively opened: the Drama Theater of the Pacific Fleet, the Primorsky Regional Puppet Theater, and the Primorsky Regional Drama Theater of Youth.[80] The regional puppet theater gave 484 performances in 2015, which were attended by more than 52,000 spectators. There are 500 puppets in the theater, where 15 artists work. The troupe regularly goes on tour from Europe to Asia.[81]

In September 2012, a granite statue of the actor Yul Brynner (1920–1985) was inaugurated in Yul Brynner Park, directly in front of the house where he was born at 15 Aleutskaya St.

Music, Opera and Ballet

The city is home to the Vladivostok Pops Orchestra.

Russian rock band Mumiy Troll hails from Vladivostok and frequently puts on shows there. In addition, the city hosted the "VladiROCKstok" International Music Festival in September 1996. Hosted by the mayor and governor, and organized by two young American expatriates, the festival drew nearly 10,000 people and top-tier musical acts from St. Petersburg (Akvarium and DDT) and Seattle (Supersuckers, Goodness), as well as several leading local bands.

Nowadays there is another annual music festival in Vladivostok, Vladivostok Rocks International Music Festival and Conference (V-ROX). Vladivostok Rocks is a three-day open-air city festival and international conference for the music industry and contemporary cultural management. It offers the opportunity for aspiring artists and producers to gain exposure to new audiences and leading international professionals.[82]

The musical theater in Vladivostok is represented by the Primorsky Regional Philharmonic Society, the largest concert organization in Primorsky Krai. The Philharmonic has organized the Pacific Symphony Orchestra and the Governor's Brass Orchestra. In 2013, the Primorsky Opera and Ballet Theater was opened.[83] On January 1, 2016 it was transformed into a branch of the Mariinsky Theatre.[84] The Russian Opera House houses the State Primorsky Opera and Ballet Theater.[85]

Museums

The Arsenyev Primorye Museum, opened in 1890, is the main museum of Primorsky Krai. Besides the main facility, it has three branches in Vladivostok itself (including Arsenyev's Memorial House), and five branches elsewhere in the state.[86] Among the items in the museum's collection are the famous 15th-century Yongning Temple Steles from the lower Amur.

Galleries and Showrooms

The active development of art museums in Vladivostok began in the 1950s. In 1960, the House of Artists was built, in which there were exhibition halls. In 1965, the Primorsky State Art Gallery was separated into a separate institution, and later, on the basis of its collection, the Children's Art Gallery was created. In Soviet times, one of the largest areas for exhibitions in Vladivostok was the exhibition hall of the Primorsky branch of the Union of Artists of Soviet Russia. In 1989 the gallery of contemporary art "Artetage" was opened.[87]

In 1995, the Arka gallery of contemporary art was opened, the first exposition of which consisted of 100 paintings donated by the collector Alexander Glezer.[88] The gallery participates in international exhibitions and fairs. In 2005, a non-commercial private gallery "Roytau" appeared.[87] In recent years, the centers of contemporary art "Salt" (created on the basis of the FEFU art museum) and "Zarya",[89][90] have been active.

Cinemas

In 2014, 21 cinemas operated in Vladivostok, and the total number of movie screenings was 1,501,000.

Most of the city's cinemas - Ocean, Galaktika, Moscow (formerly called New Wave Cinema), Neptune 3D (formerly called Neptune and Borodino), Illusion, Vladivostok - are renovated cinemas built in the Soviet years. Among them stands out "Ocean" with the largest (22 by 10 meters) screen in the Far East of the country, located in the center of the city in the area of Sports Harbor.[91] Together with the cinema "Ussuri", it is the venue for the annual international film festival "Pacific Meridians" (since 2002).[92] Since December 10, 2014 the IMAX 3D hall has been operating in the Ocean cinema.[93]

Parks and squares

Parks and squares in Vladivostok include Pokrovskiy Park, Minnyy Gorodok, Detskiy Razvlekatelnyy Park, Park of Sergeya Lazo, Admiralskiy Skver, Skver im. Neveskogo, Nagornyy Park, Skver im. Sukhanova, Fantaziya Park, Skver Rybatskoy Slavy, Skver im. A.I.Shchetininoy.

Pokrovskiy Park

Pokrovskiy Park was once a cemetery. Converted into a park in 1934 but was closed in 1990. Since 1990 the land the park sits on belongs to the Russian Orthodox Church. During the rebuilding of the Orthodox Church, graves were found.

Minny Gorodok

Minny Gorodok is a 91-acre (37 ha) public park. Minny Gorodok means "Mine Borough Park" in English. The park is a former military base that was founded in 1880. The military base was used for storing mines in underground storage. Converted into a park in 1985, Minny Gorodok contains several lakes, ponds, and an ice-skating rink.

Detsky Razvlekatelny Park

Detsky Razvlekatelny Park is a children's amusement park located near the centre of the city. The park contains a carousel, gaming machines, a Ferris wheel, cafés, an aquarium, cinema, and a stadium.

Admiralsky Skver

Admiralsky Skver is a landmark located near the city's centre. The Square is an open space, dominated by the Triumfalnaya Arka. South of the square sits a museum of Soviet submarine S-56.

Sports

Vladivostok is home to the football club FC Luch-Energiya Vladivostok, who plays in the Russian First Division, ice hockey club Admiral Vladivostok from the Kontinental Hockey League's Chernyshev Division, and basketball club Spartak Primorye, who plays in the Russian Basketball Super League.

Pollution

Local ecologists from the Ecocenter organization have claimed that much of Vladivostok's suburbs are polluted and that living in them can be classified as a health hazard. The pollution has a number of causes, according to Ecocenter geo-chemical expert Sergey Shlykov. Vladivostok has about eighty industrial sites, which may not be many compared to Russia's most industrialized areas, but those around the city are particularly environmentally unfriendly, such as shipbuilding and repairing, power stations, printing, fur farming, and mining.

In addition, Vladivostok has a particularly vulnerable geography which compounds the effect of pollution. Winds cannot clear pollution from some of the most densely populated areas around the Pervaya and Vtoraya Rechka as they sit in basins which the winds blow over. In addition, there is little snow in winter and no leaves or grass to catch the dust to make it settle down.[94]

Twin towns - sister cities

Vladivostok is twinned with:[95]

Akita, Japan

Akita, Japan Busan, South Korea

Busan, South Korea Dalian, Liaoning, China

Dalian, Liaoning, China Hakodate, Japan

Hakodate, Japan Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

Harbin, Heilongjiang, China Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Incheon, South Korea

Incheon, South Korea Juneau, Alaska, United States

Juneau, Alaska, United States Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia Manta, Ecuador

Manta, Ecuador Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain

Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain Niigata, Japan

Niigata, Japan Pohang, South Korea

Pohang, South Korea San Diego, California, United States

San Diego, California, United States Tacoma, Washington, United States

Tacoma, Washington, United States Vladikavkaz, Russia

Vladikavkaz, Russia Wonsan, North Korea

Wonsan, North Korea Yanbian, Jilin, China

Yanbian, Jilin, China

In 2010, arches with the names of each of Vladivostok's twin towns were placed in a park within the city.[96]

From Vladivostok ferry port next to the train station, a ferry of the DBS Cruise Ferry travels regularly to Donghae, South Korea and from there to Sakaiminato on the Japanese main island of Honshu.

Notable people

- Alexandra Biriukova (1895–1967), architect

- Alexei Volkonski (born 1978), canoeist

- Anna Shchetinina (1908–1999), captain

- Elmar Lohk (1901–1963), architect

- Eugene Kozlovsky (born 1946), writer

- Feliks Gromov (1937–), admiral

- Igor Ansoff (1918–2002), mathematician

- Igor Kunitsyn (born 1981), tennis player

- Igor Tamm (1895–1971), physicist

- Ilya Lagutenko (born 1968), singer

- Ivan Vasiliev (born 1989), ballet dancer

- Kristina Rihanoff (born 1977), dancer

- Ksenia Kahnovich (born 1987), model

- Lev Knyazev (1924–2012), writer

- Liah Greenfeld (born 1954), academic

- Mary Losseff (1907–1972), singer, film actor

- Mikhail Koklyaev (born 1978), strongman

- Natalia Pogonina (born 1985), chess player

- Nikolay Dubinin (1907–1998), biologist

- Peter A. Boodberg (1903–1972), scholar, linguist

- Stanislav Petrov (1939–2017), soldier, averted nuclear war

- Svoy (born 1980), musician

- Swathi Reddy (born 1987), Indian actress

- Victor Zotov (1908–1977), botanist

- Vitali Kravtsov (born 1999), ice hockey forward

- Vladimir Arsenyev (1872–1930), explorer

- Vladimir Ossipoff (1907–1998), architect

- Wes Hurley (born 1981), filmmaker

- Yi Dong-hwi (1873–1935), Korean communist

- Yul Brynner (1920–1985), film actor

References

Notes

- Law #161-KZ

- Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 72. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- "Обвиняемый во взятках мэр Владивостока подал в отставку".

- "Генеральный план Владивостока". Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Правительство Приморского края". Официальный сайт Правительства Приморского края.

- Law #179-KZ

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- Ростелеком завершил перевод Владивостока на семизначную нумерацию телефонов (in Russian). July 12, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- "RUSSIA: Dal'nevostočnyj Federal'nyj Okrug". City Population.de. August 8, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- Екатерина Века (February 7, 2018). "Владивосток вошёл в топ-5 самых популярных у туристов городов России". Администрация Приморского края. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Alexander Jacoby (July 5, 2005). "Eastern Europe in the Far East". The Japan Times. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- Alex Nosal. "Vladivostok, Europe in Middle of The Orient". The Seoul Times. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- "Distance Vladivostok, Primorsky-Krai, RUS → Darwin, Northern Territory, AUS". Distance.to. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- "Distance Vladivostok, Primorsky-Krai, RUS → Moscow, RUS". Distance.to. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- В. В. Постников. (V. V. Postinkov.) "К осмыслению названия 'Владивосток': историко-политические образы Тихоокеанской России." ("To the comprehension of the name "Vladivostok": historical and political images of the Pacific Russia.") Ойкумена. (Ojkumena.) Vol. 4. July 2010. p. 75. (in Russian)

- “海参崴来自满语,意为‘海边的小渔村’”:阳, 曹. "冰雪黑龙江 圣诞异国游--频道风采". 天津广播网. 天津人民广播电台交通广播. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Владивосток все же стал Хайшенвеем". Novostivl.ru. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2017. (in Russian)

- Kee, Kwonho (2001). 中共對韓半島外交政策: 從辯證法的角度研究 [Mainland China's foreign policy in the Korean Peninsula: a dialectical analysis] (PDF) (in Chinese). National Sun Yat-sen University. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- 公开地图内容表示若干规定 (in Chinese). Ministry of Land and Resources of the People's Republic of China. January 19, 2006.

- Narangoa 2014, p. 300.

- Turmov G.P., Khisamutdinov A.A. Vladivostok. Historical guide. - M .: Veche, 2010. - 304 p. - ISBN 978-5-9533-4924-6.

- Old Vladivostok. / Auth. text and comp. B. Dyachenko. - Vladivostok: Morning of Russia, 1992. - P. 51. - 36,000 copies. - ISBN 5-87080-004-8.

- Старый Владивосток. / Авт. текста и сост. Б. Дьяченко. — Владивосток: Утро России, 1992. — С. 51. — 36 000 экз. — ISBN 5-87080-004-8

- Юрий Уфимцев. "Основание Владивостока". oldvladivostok.ru. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Владивосток: история города". RIA Novosti. February 7, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Особенности промышленно-экономического развития Владивостока в начале XX века". CyberLeninka. 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Вольная гавань: общественная жизнь дореволюционного Владивостока". CyberLeninka. 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Ясько Т. Н. "Сибирская военная флотилия в 1917—1922 гг". fegi.ru. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Дежурный по Редакции (November 29, 2015). "Архангельский и Владивостокский порты в годы Первой мировой войны". Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 38 - 50, 52 - 102, 124 - 128,140 - 148,184 - 190

- Joana Breidenbach (2005). Pál Nyíri, Joana Breidenbach (ed.). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 90. ISBN 963-7326-14-6. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

Then there occurred another story which has become traumatic, this one for the Russian nationalist psyche. At the end of the year 1918, after the Russian Revolution, the Chinese merchants in the Russian Far East demanded the Chinese government to send troops for their protection, and Chinese troops were sent to Vladivostok to protect the Chinese community: about 1600 soldiers and 700 support personnel.

- Владимир Гелаев. (April 6, 2015). "Новороссия Дальнего Востока". Gazeta.Ru. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Ковалёва З. А., Плохих С. В. (2002). "История Дальнего Востока России" (PDF). Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Кривенко С. "Владивостокский ИТЛ". Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Галина Ткачева (October 10, 2019). "Великая Отечественная во Владивостоке: как и чем жил город в военное время". PrimaMedia.ru. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Владивостокские порты". Камчатский научный центр. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Виктория Антошина (October 12, 2015). "Закрытый на 40 лет Владивосток: штамп "ЗП" в паспорте, фарцовка и фальшивые портовики". PrimaMedia.ru. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Власов С. А. (2010). "Владивосток в годы хрущевской "оттепели"" (PDF). Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Александр Львович Ткачев (April 27, 2011). "Первый визит президента США / First Visit of an American President". alltopprim.ru. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "УКАЗ Президента РСФСР от 20.09.1991 N 123 "ОБ ОТКРЫТИИ Г. ВЛАДИВОСТОКА ДЛЯ ПОСЕЩЕНИЯ ИНОСТРАННЫМИ ГРАЖДАНАМИ"". kremlin.ru. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Levy, Clifford J. "Crisis or Not, Russia Will Build a Bridge in the East," New York Times. 20 April 2009.

- "Putin proposes Russky Island venue for APEC-2012". Vladivostok: Vladivostok News. January 31, 2007. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- Williamson, Gail M.; Christie, Juliette (September 18, 2012). Lopez, Shane J; Snyder, C.R (eds.). "Aging Well in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities". Oxford Handbooks Online: 164–170. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0015. ISBN 9780195187243.

- Климат Владивостока [Climate of Vladivostok]. Погода и Климат (Weather and Climate) (in Russian). Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- "Climate Vladivostok". Pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- "VLADIVOSTOK 1961–1990". NOAA. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- "ст. 20 Устава города Владивостока". Официальный сайт Администрации города Владивостока. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Дума города Владивостока празднует 140-летие". Официальный сайт Администрации города Владивостока. December 11, 2015. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Устав города". vlc.ru. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Исполнять обязанности мэра Владивостока будет Константин Лобода". newsvl.ru. June 27, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Об итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года на территории Владивостокского городского округа" (PDF). Сайт Владивостока. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Численность постоянного населения Приморского края в разрезе городских округов и муниципальных районов". Приморскстат РФ. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Численность постоянного населения Приморского края в разрезе городских округов и муниципальных районов". Приморскстат РФ. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Федеральная служба государственной статистики". rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "4. Население по национальности и владению русским языком" (PDF). Приморскстат РФ. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- Сидоркина З. И. (2015). "Миграция в крупных городах Дальнего Востока" (PDF). Дальневосточное отделение Российской академии наук. pp. 15–22. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- Егор Кузьмичев (September 25, 2014). "Японская "Мозаика" и эстонские "Корни"". Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Putin Is Turning Vladivostok into Russia's Pacific Capital" (PDF). Russia Analytical Digest. Institute of History, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland (82): 9–12. July 12, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011.

- Oliphant, Roland (2010). "Ruler of the East: The City of Vladivostok Is a Mixture of Promise and Neglect". Russia Profile.

- "Морской порт Владивосток". pma.ru. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Грузооборот морских портов России за январь-декабрь 2016 г." morport.com. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Исследование и анализ торговых ограничений внешней торговли в городе Владивосток". CyberLeninka. 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Татьяна Сушенцова (June 20, 2016). "Приморский край: есть чем впечатлиться". Дальневосточный капитал. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Сергей Павлов (May 26, 2016). "Властелины Восточного кольца". Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Формирование туристской идентичности г. Владивостока в контексте бренда: "Владивосток — морские ворота России"". CyberLeninka. 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Оздоровительный туризм как фактор развития территории на примере побережья залива Петра Великого, Японское море". CyberLeninka. 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Andrew Higgins (July 1, 2017). "In Russia's Far East, a Fledgling Las Vegas for Asia's Gamblers". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Heldi Specter (November 19, 2019). "Primorye Gamblng Zone to Welcome at Least 11 Casinos". Gambling News. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Такаюки Танака (May 16, 2016). "Судьба развития Дальнего Востока — в руках казино: Владивосток привлекает азиатских клиентов". inoSMI. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Ольга Цыбульская. "Во Владивостоке хорошие деловые перспективы". РБК. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Анализ структуры регионального туристического комплекса Приморского края России". CyberLeninka. 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Три школы Владивостока вошли в перечень "Топ-500 школ РФ"". RIA Novosti. September 18, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Анна Бондаренко (September 1, 2016). "В Приморье открылся филиал Вагановской Академии балета". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- "Выступление на встрече с воспитанниками филиала Нахимовского военно-морского училища во Владивостоке". Президент России. August 31, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- "Новые возможности высшего образования на Дальнем Востоке России: от Восточного института к Дальневосточному Федеральному Университету". CyberLeninka. 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- "Закулисье театра имени Максима Горького: швейный цех, большие склады и маленькие гримерки". PrimaMedia.ru. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Фалалеева А. В. (March 25, 2014). "Театр, театр, театр…(о театрах города Владивостока)". cbs.fokino25.ru. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "В Приморском театре кукол побывало более 50 тысяч зрителей на 500 спектаклях в 2015 году". PrimaMedia.ru. June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Ryzik, Melena (August 28, 2013). "East by Far East: Vladivostok Rocks". The New York Times.

- "Семь фестивалей, 14 оперных и балетных спектаклей — два года Приморского оперного театра". PrimaMedia.ru. October 19, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "Приморский филиал Мариинского театра". Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Starrs. "Russian Opera house".

- "Музей истории Дальнего Востока имени В.К. Арсеньева". Приморский музей имени Арсеньева. July 6, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012.

- "Развитие сети художественных музеев в Приморском крае". 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "События в мире в 1995 году". history.xsp.ru. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Василий Алленов (March 3, 2016). ""Соль" современного искусства". Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "Центр современного искусства открылся на фабрике "Заря" во Владивостоке". PrimaMedia.ru. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "Кинотеатры Владивостока: где Dolby Digital и 3D, где храмы и руины". RIA Novosti. December 29, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "8 сентября во Владивостоке начинается международный кинофестиваль "Меридианы Тихого"". kbanda.ru. September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- "IMAX приходит на Дальний Восток". kinobusiness.com. December 11, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- B. V. Preobrazhensky, A. I. Burago, S. A. Shlykov. Primorye Ecology. Ecological Situation. Contamination of Sea and Water Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Города-побратимы". vlc.ru (in Russian). Vladivostok. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Во Владивостоке открыт сквер городов-побратимов (In Russian). Retrieved July 19, 2016.

Sources

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №161-КЗ от 14 ноября 2001 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края», в ред. Закона №673-КЗ от 6 октября 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Красное знамя Приморья", №69 (119), 29 ноября 2001 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #161-KZ of November 14, 2001 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai, as amended by the Law #673-KZ of October 6, 2015 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai". Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №179-КЗ от 6 декабря 2004 г. «О Владивостокском городском округе», в ред. Закона №48-КЗ от 7 июня 2012 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "О Владивостокском городском округе"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2005 г.. Опубликован: "Ведомости Законодательного Собрания Приморского края", №76, 7 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #179-KZ of December 6, 2004 On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug, as amended by the Law #48-KZ of June 7, 2012 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug". Effective as of January 1, 2005.).

- Faulstich, Edith. M. "The Siberian Sojourn" Yonkers, N.Y. (1972–1977)

- Narangoa, Li (2014). Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590-2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231160704.

- Poznyak, Tatyana Z. 2004. Foreign Citizens in the Cities of the Russian Far East (the second half of the 19th and 20th centuries). Vladivostok: Dalnauka, 2004. 316 p. (ISBN 5-8044-0461-X).

- Stephan, John. 1994. The Far East a History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994. 481 p.

- Trofimov, Vladimir et al., 1992, Old Vladivostok. Utro Rossii Vladivostok, ISBN 5-87080-004-8

External links

| Wikinews has news related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Vladivostok. |

- Official website of Vladivostok (in Russian)

- Vladivostok at the Encyclopædia Britannica

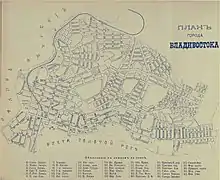

- Historical Map of Vladivostok (1912), Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

- Timelapse video of Vladivostok on YouTube (in Russian)