Crested eagle

The crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis) is a large Neotropical eagle.

| Crested eagle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Perched in a tree eating an emerald tree boa in Bolivia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Subfamily: | Harpiinae |

| Genus: | Morphnus Dumont, 1816 |

| Species: | M. guianensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Morphnus guianensis (Daudin, 1800) | |

| |

It is the only member of the genus Morphnus.

Description

This species is a large but slender eagle. It measures 71–89 cm (28–35 in) long and has a wingspan of 138–176 cm (55–70 in). A small handful of crested eagles have been weighed, entirely either males or unsexed birds, and have scaled from 1.3 to 3 kg (2.9 to 6.6 lb). Standard measurements have indicated females are about 14% larger on average than males.[2][3]

The crested eagle has a large head, an effect enhanced by the often extended feather crest of its name. It has bare legs, with a sizable tarsus length of 10.3 to 11.2 cm (4.1 to 4.4 in). The tail is fairly long, measuring 34 to 43 cm (13 to 17 in) in length. The wings are quite short for the eagle's size but are broad and rounded. Forest-dwelling raptors often have a relatively small wingspan in order to enable movement within the dense, twisted forest environments. The wing chord measures 42.5–48.5 cm (16.7–19.1 in). The plumage of the crested eagle is somewhat variable. The head, back and chest of most adults are light brownish-gray, with a white throat and a dark spot on the crest and a small dark mask across the eyes. There are also various dark morphs where the plumage is sooty-gray or just blackish in some cases. The distinctive juvenile crested eagle is white on the head and chest, with a marbled-gray coloration on the back and wings. They turn to a sandy-gray color in the second year of life. Dark morph juveniles are similar but are dark brownish-gray from an early age. In flight, crested eagles are all pale below except for the grayish coloration on the chest.

This species often overlaps in range with the less scarce Harpy eagle, which is likely its close relative and is somewhat similar to appearance. There is evidence of an interesting interspecific relationship between and adult Crested eagle feeding a juvenile Harpy eagle in Panama, while the adult Harpy eagles were away. During these interactions, the Crested eagle brought new nesting material to the nest and in occasions brought food to the juvenile Harpy eagle.[4] The Crested eagle is roughly half that species' bulk and is clearly more slender. Generally, Crested eagles are silent but do make a call occasionally that consists of a pair of high whistles, with the second whistle being higher pitched than the first.

Distribution and habitat

It is sparsely distributed throughout its extensive range from northern Guatemala through Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama,[4] the subtropical Andes of Colombia, northeastern Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Brazil (where it has suffered greatly from habitat destruction,[5] being now found practically only in the Amazonian basin[6]), and east Andean Ecuador, southeastern Peru, Paraguay and eastern Bolivia to north Argentina.

The crested eagle lives in humid lowland forests, mostly comprised by tropical rainforests. They can also range in gallery strips and forest ravines. Over most of the range, sightings of the species are from sea level to 600 m (2,000 ft). However, in the Andean countries, they appear to be local residents in foothill forests up to 1,000 m (3,300 ft) elevation or even 1,600 m (5,200 ft).

Ecology

The crested eagle may avoid direct competition with the harpy eagle by taking generally smaller prey. Birds may comprise a larger portion of the diet for crested than they do for harpys. Birds such as jays, trumpeters and guans have been observed to be predated at fruiting trees and male cocks-of-the-rock have been predated while conspicuously performing at their leks. However, the crested eagle is certainly a powerful avian predator in its own right and most studies have indicated they are primarily a predator of small mammals. Often reflected in the diet are small monkeys, such as capuchin monkeys,[7] tamarins,[8] and woolly monkeys. Other mammalian prey may include numerous arboreal rodents as well as opossums and kinkajous. Various studies have also pointed to the abundance of snakes (both arboreal and terrestrial varieties) and other reptiles (principally lizards) in its prey base, but the relative frequency of different types of prey apparently varies greatly on the individual level.[9] The crested eagle seems to be a still-hunter, as it has been observed perched for long periods of time while visual scanning the forest around them.

The crested eagle is almost always observed singly or in pairs. The breeding season is from March–April (the borderline between the dry season and the wet season in the neotropics) onwards. The nest is often huge but has a shallow cup and is typically in the main fork of a large tree, often concealed near the canopy in greenery. No further details are known of the breeding or brooding behavior of the species.

Status

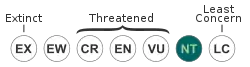

The crested eagle has always seemed to occur at low densities and may occasionally elude detection in areas where they do occur. Though they still have a large distribution, they are currently classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN.[1] Due to their seemingly high dependence on sprawling forest, they are highly affected by habitat destruction. They are believed to no longer occur in several former breeding areas where extensive forest have been cleared. It is thought that they are occasionally hunted by local people and, in some cases, are shot on sight. If discovered while perched, they are relatively easy to shoot, since they usually perch for extended periods of time.

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Morphnus guianensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James Ferguson-Lees (15 October 2001). Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Hilty, Steven L. Birds of Venezuela. Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Vargas G., Jose de J. "Crested Eagle (Morphnus Guianensis) Feeding a Post-Fledged Young Harpy Eagle (Harpia Harpyja) in Panama" (PDF).

- Jorge Luiz B. Albuquerque; et al. (2006). "Águia-cinzenta (Harpyhaliaetus coronatus) e o Gavião-real-falso (Morphnus guianensis) em Santa Catarina e Rio Grande do Sul: prioridades e desafios para sua conservação" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 14 (4): 411–415. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-26.

- Uiraçu-falso (in Portuguese). eln.gov.br

- Uiraçu-falso. Wikiaves.com.br (2012-06-29). Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- Oversluijs Vasquez, MR; Heymann, EW (2001). "Crested Eagle (Morphnus guianensis) Predation on Infant Tamarins (Saguinus mystax) and Saguinus fuscicollis, Callitrichinae)". Folia Primatologica. 72 (5): 301–3. doi:10.1159/000049952. PMID 11805427.

- Cf. Gavião-real-falso (Morphnus guianensis). avesderapinabrasil.com

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. & Franklin, Kim (2005): Raptors of the world: a Field Guide. Christopher Helm, London & Princeton. ISBN 0-7136-6957-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morphnus guianensis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Morphnus guianensis. |

.jpg.webp)