Crushing (execution)

Death by crushing or pressing is a method of execution that has a history during which the techniques used varied greatly from place to place, generally involving the placement of intense weight upon a person with the intent to kill. This form of execution is no longer used by any government.

Crushing by elephant

A common method of death throughout South and South-East Asia for over 4,000 years was crushing by elephants. The Sasanians, Romans, and Carthaginians also used this method on occasion.

Roman mythology

In Roman mythology, Tarpeia was a Roman maiden who betrayed the city of Rome to the Sabines in exchange for what she thought would be a reward of jewelry. She was instead crushed to death and her body cast from the Tarpeian Rock which now bears her name.[1]

Crushing in pre-Columbian America

Crushing is also reported from pre-Columbian America, notably in the Aztec Empire.[2][3]

Crushing under common law

Peine forte et dure (Law French for "forceful and hard punishment") was a method of torture formerly used in the common law legal system, in which a defendant who refused to plead ("stood mute") would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon his or her chest until a plea was entered, or as the weight of the stones on the chest became too great for the condemned to breathe, fatal suffocation would occur.

The common law courts originally took a very limited view of their own jurisdiction. They considered themselves to lack jurisdiction over a defendant until he had voluntarily submitted to it by entering a plea seeking judgment from the court.[4] Since a criminal justice system that tried and punished only those who volunteered for trial and punishment was practically unworkable, this was the means chosen to coerce them.[5]

Many defendants charged with capital offences nonetheless refused to plead, since thereby they would escape forfeiture of property, and their heirs would still inherit their estate; but if the defendant pleaded guilty and was executed, their heirs would inherit nothing, their property escheating to the Crown. Peine forte et dure was abolished in Great Britain in 1772, and the last known use of the practice was in 1741.[6] In 1772, refusing to plead was deemed to be equivalent to pleading guilty. This was changed in 1827 to being deemed a plea of not guilty. Today, in all common law jurisdictions, standing mute is treated by the courts as equivalent to a plea of not guilty.

The elaborate procedure was recorded by a 15th-century witness in an oft-quoted description: "he will lie upon his back, with his head covered and his feet, and one arm will be drawn to one quarter of the house with a cord, and the other arm to another quarter, and in the same manner it will be done with his legs; and let there be laid upon his body iron and stone, as much as he can bear, or more ..."[7]

"Pressing to death" might take several days, and not necessarily with a continued increase in the load. The Frenchman Guy Miege, who from 1668 taught languages in London[8] says the following about the English practice:[9]

For such as stand Mute at their Trial, and refuse to answer Guilty, or Not Guilty, Pressing to Death is the proper Punishment. In such a Case the Prisoner is laid in a low dark Room in the Prison, all naked but his Privy Members, his Back upon the bare Ground his Arms and Legs stretched with Cords, and fasten'd to the several Quarters of the Room. This done, he has a great Weight of Iron and Stone laid upon him. His Diet, till he dies, is of three Morsels of Barley bread without Drink the next Day; and if he lives beyond it, he has nothing daily, but as much foul Water as he can drink three several Time , and that without any Bread: Which grievous Death some resolute Offenders have chosen, to save their Estates to their Children. But, in case of High Treason, the Criminal's Estate is forfeited to the Sovereign, as in all capital Crimes, notwithstanding his being pressed to Death.

The most famous case in the United Kingdom was that of Roman Catholic martyr St Margaret Clitherow, who (in order to avoid a trial in which her own children would be obliged to give evidence) was pressed to death on March 25, 1586, after refusing to plead to the charge of having harboured Catholic (then outlawed) priests in her house. She died within fifteen minutes under a weight of at least 700 pounds (320 kg). Several hardened criminals, including William Spigott (1721) and Edward Burnworth, lasted a half hour under 400 pounds (180 kg) before pleading to the indictment. Others, such as Major Strangways (1658) and John Weekes (1731), refused to plead, even under 400 pounds (180 kg), and were killed when bystanders, out of mercy, sat on them.[10]

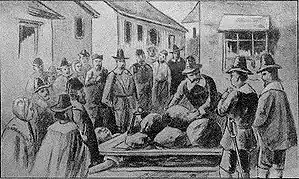

The only death by peine forte et dure in American history was Giles Corey, who was pressed to death on September 19, 1692, during the Salem witch trials, after he refused to enter a plea in the judicial proceeding. According to legend, his last words as he was being crushed were "More weight", and he was thought to be dead as the weight was applied. This is referred to in Arthur Miller's political drama The Crucible (1953), where Giles Corey is pressed to death after refusing to plead "aye or nay" to the charge of witchcraft. In the 1996 film version of this play, the screenplay also written by Arthur Miller, Corey is crushed to death for refusing to reveal the name of a source of information.

In medieval Europe, the slow crushing of body parts in screw-operated "bone vises" of iron was a common method of torture, and a tremendous variety of cruel instruments were used to savagely crush the head, knee, hand, and, most commonly, either the thumb or the naked foot. Such instruments were finely threaded and variously provided with spiked inner surfaces or heated red-hot before their application to the limb to be tortured.

See also

References

- Sanders, H. (1904). Roman historical sources and institutions. Macmillan. pp. 1–47.

- Summerson, Henry (1983). "The Early Development of Peine Forte et Dure."

- Law, Litigants, and the Legal Profession: Papers Presented to the Fourth British Legal History Conference at the University of Birmingham 10–13 July 1979 ed E. W. Ives & A. H. Manchester, 116-125. Royal Historical Society Studies in History Series 36. London: Humanities Press.

- Sir Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, The History of English Law, v. 2, pp. 650–651 (Cambridge; 1968; ISBN 0-521-07062-7)

- See generally, William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1769), vol. 4, pp. *319-324

- Drug Control and Asset Seizures: a review of the history of forfeiture in England and colonial America Archived 28 April 1997 at the Wayback Machine

- Curiosities of Cowell's "Interpreter"

- The enterprising and tenacious Guy Miège: four dictionaries from 1677 to 1688

- Miege, G.:"The present state of Great-Britain and Ireland" London 1715, p.294

- "Mackenzie, The Practise of Peine Forte et Dure in 16th and 17th Century England". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2009.