Flaying

Flaying, also known colloquially as skinning, is a method of slow and painful execution in which skin is removed from the body. Generally, an attempt is made to keep the removed portion of skin intact.

Scope

A dead animal may be flayed when preparing it to be used as human food, or for its hide or fur. This is more commonly called skinning.

Flaying of humans is used as a method of torture or execution, depending on how much of the skin is removed. This is often referred to as "flaying alive". There are also records of people flayed after death, generally as a means of debasing the corpse of a prominent enemy or criminal, sometimes related to religious beliefs (e.g. to deny an afterlife); sometimes the skin is used, again for deterrence, esoteric/ritualistic purposes, etc. (e.g. scalping).

Causes of death

Dermatologist Ernst G. Jung notes that the typical causes of death due to flaying are shock, critical loss of blood or other body fluids, hypothermia, or infections, and that the actual death is estimated to occur from a few hours up to a few days after the flaying.[1] Hypothermia is possible, as skin provides natural insulation and is essential for maintaining body temperature.

History

Assyrian tradition

Ernst G. Jung, in his Kleine Kulturgeschichte der Haut ("A short cultural history of the skin"), provides an essay in which he outlines the Neo-Assyrian tradition of flaying human beings.[2] Already from the times of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883-859 BC), the practice is displayed and commemorated in both carvings and official royal edicts. The carvings show that the actual flaying process might begin at various places on the body, such as at the crus (lower leg), the thighs, or the buttocks.

In their royal edicts, the Neo-Assyrian kings seem to gloat over the terrible fate they imposed upon their captives, and that flaying seems, in particular, to be the fate meted out to rebel leaders. Jung provides some examples of this triumphant rhetoric. From Ashurnasirpal II:

I have made a pillar facing the city gate, and have flayed all the rebel leaders; I have clad the pillar in the flayed skins. I let the leaders of the conquered cities be flayed, and clad the city walls with their skins. The captives I have killed by the sword and flung on the dung heap, the little boys and girls were burnt.

The Rassam cylinder in the British Museum describes this:

Their corpses they hung on stakes, they stripped off their skins and covered the city wall with them.[3]

Other examples

Searing or cutting the flesh from the body was sometimes used as part of the public execution of traitors in medieval Europe. A similar mode of execution was used as late as the early 18th century in France; one such episode is graphically recounted in the opening chapter of Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish (1979).

In 1303, the treasury of Westminster Abbey was robbed while holding a large sum of money belonging to King Edward I. After the arrest and interrogation of 48 monks, three of them, including the subprior and sacrist, were found guilty of the robbery and flayed. Their skin was attached to three doors as a warning against robbers of church and state.[4] At St Michael & All Angels' Church in Copford in Essex, England, it is claimed that human skin was found attached to an old door, though evidence seems elusive.[5]

In Chinese history, Sun Hao, Fu Sheng and Gao Heng were known for removing skin from people's faces.[6] The Hongwu Emperor flayed many servants, officials and rebels.[7][8] In 1396 he ordered the flaying of 5000 women.[9] Hai Rui suggested that his emperor flay corrupt officials. The Zhengde Emperor flayed six rebels,[10] and Zhang Xianzhong also flayed many people.[11] Lu Xun said the Ming dynasty was begun and ended by flaying.[12]

Examples and depictions of flayings

Artistic

%252C_V%2526A.JPG.webp)

- One of the plastinated exhibits in Body Worlds includes an entire posthumously flayed skin, and many of the other exhibits have had their skin removed.

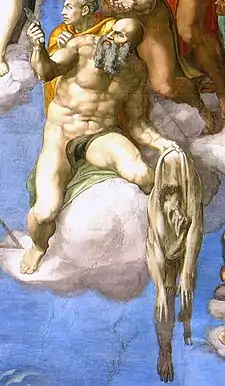

Mythological

- In Greek mythology, Marsyas, a satyr, was flayed alive after losing a musical contest to Apollo.

- Also according to Greek mythology, Aloeus is said to have had his wife flayed.

- In Aztec mythology, Xipe Totec is the flayed god of death and rebirth. Captured enemy warriors were flayed annually as sacrifices to him.

Historical

- Yahu-Bihdi, ruler of Hamath, was flayed alive by the Assyrians under Sargon II.

- According to Herodotus, Sisamnes, a corrupt judge under Cambyses II of Persia, was flayed for accepting a bribe.

- The Talmud discusses how Rabbi Akiva was flayed alive by the Romans for publicly teaching Torah.

- Catholic and Orthodox tradition holds that Saint Bartholomew was flayed before being crucified.

- In 260 AD, the Roman emperor Valerian was seized during a parley by Shapur I, king of Persia, at Edessa. According to some accounts he was flayed alive.

- Mani, founding prophet of Manichaeism, was said to have been flayed or beheaded (c. 275).

- In March 415, Hypatia of Alexandria, a Neoplatonist philosopher, was murdered by a Christian mob of Nitrian monks who accused her of paganism. They stripped her naked, skinned her with ostraca (pot shards), and then burned her remains.[13]

- Totila is said to have ordered the bishop of Perugia, Herculanus, to be flayed when he captured that city in 549.

- In 991 AD, during a Viking raid in England, a Danish Viking is said to have been flayed by London locals for ransacking a church. Alleged human skin found on a local church door has, for many years, been considered as proof for this legend, but a deeper analysis made during the production of the 2001 BBC documentary, Blood of the Vikings, came to the conclusion that the preserved skin came from a cow hide and was part of a 19th-century hoax.

- Pierre Basile was flayed alive and all defenders of the chateau hanged on 6 April 1199, by order of the mercenary leader Mercadier, for shooting and killing King Richard I of England with a crossbow at the siege of Châlus, in March 1199.[14]

- In 1314, the brothers Aunay, who were lovers of the daughters-in-law of king Philip IV of France, were flayed alive, then castrated and beheaded, and their bodies were exposed on a gibbet (Tour de Nesle Affair). The extreme severity of their punishment was due to the lèse majesté nature of the crime.

- In 1323, the Mexica tribe asked for Yaocihuatl, daughter of Achicometl, ruler of Culhuacan in marriage. Unknown to him, she was sacrificed, with the priest appearing during the festival dinner wearing her skin as part of the ritual. (History of the Aztecs)

- In 1404 or 1417, the Hurufi Imad ud-Din Nesîmî, an Islamic poet of Turkic extraction, was flayed alive, apparently on orders of a Timurid governor, and for heresy.

- In August 1571, Marcantonio Bragadin, a defeated Venetian commander, was flayed to death by the Ottomans, causing enormous outrage in Venice and perhaps inspiring Titian's Flaying of Marsyas.[15]

- In 1657, the Polish Jesuit martyr, Andrew Bobola, was burned, half strangled, partly flayed alive, and killed by a sabre stroke by Eastern Orthodox Cossacks.

- In 1771, Daskalogiannis, a Cretan rebel against the Ottoman Empire, was flayed alive, and it is said that he suffered in dignified silence.

- In the United States, Nat Turner, leader of an unsuccessful slave rebellion in Virginia, was hanged on November 11, 1831. His body was then flayed, beheaded, and quartered.

- In Marcel Ophüls' documentary, Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, the daughter of a French Resistance leader claims her father was tortured, including being flayed, by Klaus Barbie during his time at Lyon, 1942-1944.

- In 1957, a victim of Ed Gein was found "dressed out like a deer". Gein appears to have been influenced by the then-current stories about the Nazis collecting body parts in order to make lampshades and other items.[16] His story fueled the inspiration of the fictional characters Norman Bates (in Psycho), Jame Gumb "Buffalo Bill" (The Silence of the Lambs), and Leatherface (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre).

Fictional

- In Thomas Harris' novel, The Silence of the Lambs, the character Buffalo Bill is a serial killer whose modus operandi includes flaying his victims.

- In the fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire and Game Of Thrones, the Boltons of the Dreadfort flay their prisoners during their independent reign, until their defeat by House Stark. The sigil of House Bolton is a flayed man tied upside down. The Boltons allegedly gave up this practice 1,000 years before the series begins; however, the sadistic bastard of the family, Ramsay Snow/Bolton, delights in flaying people and wants to restore its use.

- The titular monster of Predator flays its victims.

- In Haruki Murakami’s novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994-1995), the character Mamiya is traumatised by having witnessed a colleague being flayed to death in Manchukuo, in the late 1930s.

- In the 2008 French movie Martyrs, a female character is flayed alive by a secret philosophical society seeking to discover the secrets of the afterlife through the creation of "martyrs".

- In the 2012 film Dredd, drug kingpin Ma-Ma orders three rogue dealers to be flayed alive before being tossed off a balcony.

- The opening case of the French crime thriller TV series, The Frozen Dead (2017), concerns a valuable horse which has been flayed and beheaded.

- In the sixth season of the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the witch Willow Rosenberg uses dark magic to flay Warren Mears alive in retaliation for the murder of her girlfriend, Tara Maclay.

See also

- Anthropodermic bibliopegy (books bound in human skin)

- Degloving

- Excarnation

- Scalping

References

- p.69 Kleine Kulturgeschichte der Haut. p. 69. Ernst G. Jung (2007).

- Paragraph based on the essay "Von Ursprung des Schindens in Assyrien" in Jung (2007), p.67-70

- Rassam Cylinder. The British Museum. & 636BC, pp. Col.1, L.52 to Col.2, L. 27.

- Andrews, William (1898). The Church Treasury of History, Custom, Folk-Lore, etc. London: Williams Andrews & Co. pp. 158–167. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Wall, J. Charles (1912), Porches and Fonts. Wells Gardner and Darton, London. pp. 41-42.

- . 中国死刑观察--中国的酷刑

- "也谈"剥皮实草"的真实性". Eywedu.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-21. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- 覃垕曬皮 Archived 2007-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- 陈学霖(2001). 史林漫识. China Friendship Publishing Company.

- History of Ming, vol.94

- "写入青史总断肠(2)". Book.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- 鲁迅. 且介亭雜文·病後雜談

- Watts, Edward Jay (2006). "Hypatia and pagan philosophical culture in the later fourth century". City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria. University of California Press. pp. 197–198. ISBN 9780520244214.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 148.

- Mariotti, Giovanni (17 August 2003). "La fine di Marsia secondo Tiziano". Il Corriere della Sera.

- Gelbin, Cathy (2003). "Metaphors of Genocide". In Duttinger; et al. (eds.). Performance and Performativity in German Cultural Studies. Peter Lang. p. 233.

Bibliography

- Jung, Ernst G. (2007). "Von Ursprung des Schindens in Assyrien", in "Kleine Kulturgeschichte Der Haut". Springer Verlag. ISBN 9783798517578.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flaying. |