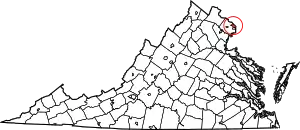

Crystal City, Arlington, Virginia

Crystal City is an urban neighborhood in the southeastern corner of Arlington County, Virginia, south of downtown Washington, D.C. Due to its extensive integration of office buildings and residential high-rise buildings using underground corridors, travel between stores, offices, and residences is possible without going above ground; thus, a large part of Crystal City is an underground city.

Crystal City, Arlington, Virginia | |

|---|---|

Crystal City in mid-2016. | |

Satellite image of the interlocking highrises of Crystal City. Richmond Highway [] (U.S. 1) (formerly Jefferson Davis Highway) can be seen running from north to south left of the image center. The main terminal of National Airport is in the bottom right corner of the image; the George Washington Memorial Parkway is to the left of the airport and right of the tree line. A few lanes of I-395 are visible in the top left corner, immediately beyond which is the Pentagon. At the bottom is State Route 233, the Airport Viaduct. Image from the United States Geological Survey, taken April 26, 2002. | |

| Coordinates: 38°51′5.05″N 77°3′2.48″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 22,543 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 22202 |

| Area code(s) | 703 |

Crystal City includes offices of numerous defense contractors, the United States Department of Labor, the United States Marshals Service and many satellite offices for The Pentagon. It is also the location of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

Geography

Crystal City is centered along a stretch of Richmond Highway (U.S. 1), just south of The Pentagon, just east of Pentagon City, and within walking distance to the west of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. Characterized as one of many "urban villages" by Arlington County, Crystal City is almost exclusively populated by high-rise apartment buildings, corporate offices, hotels, and numerous shops and restaurants. There is also an extensive network of underground shopping areas and connecting corridors beneath Crystal City.

Crystal City has a station on the Washington Metro Blue and Yellow Lines, and another on the Virginia Railway Express commuter train system.

The layout of Crystal City was considered avant-garde at the time of construction, with superblocks bounded by arterial and circulating roads, and with pedestrian traffic and the businesses serving it relocated from the streets to the pedestrian tunnels. However, Crystal City has since been redesigned to give it a more traditional, urban feel, with restaurants at street level, and with traffic patterns changed to make streets like Crystal Drive function as city streets, rather than as circulating roads.[1]

As a consequence of Crystal City's extensive integration with both office buildings and residential high-rise buildings, it is possible for most residents living to the east of Route 1 to traverse from one end to the other (roughly north-south), performing shopping or dining along the way, entirely underground, thus making a large part of Crystal City an underground city. This is of particular convenience during inclement weather.

History

Before development by the Charles E. Smith Company, the area was mostly composed of industrial sites, junkyards, and low-rent motels. A drive-in theater existed at the intersection of Jefferson Davis Highway and 20th Street South between 1947 and 1963 and is visible on aerial photos of the period. The RF&P railroad tracks were moved closer to National Airport to accommodate more space for development.

Though it is not a planned community, it unfolded in much that fashion after construction began on the first few condominiums and office buildings in 1963. The name "Crystal City" came from the first building, which was called Crystal House and had an elaborate crystal chandelier in the lobby. Every subsequent building took on the Crystal name (e.g., Crystal Gateway, Crystal Towers) and eventually the whole neighborhood. Crystal City is largely integrated in layout and extensive landscaping, as well as the style and materials of the high rise buildings, most of which have a speckled granite exterior.

Crystal City's Crystal Underground shopping mall opened in September 1976. Billed as a "turn-of-the-century shopping village," it featured antique leaded glass shop windows and cobblestone "streets." Emphasis was on locally owned and operated businesses and personalized service. The largest retail outlets were a 12,000-square-foot (1,100 m2) Jelleff's women's store, Larimers gourmet grocery and delicatessen, and a Drug Fair. The mall also featured an "Antique Alley" with small antique and craft stores. At opening there were 40 stores, with an anticipated expansion of 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) with 70 more shops including the Crystal Palace food court.[2]

On June 26, 2004, the Crystal City area underwent a number of changes. Many buildings' addresses were changed on this date, several major roads were turned into two-way streets, and many of the markings for the traditional building names (e.g., "Crystal Gateway 1") were removed. As a result, local residents may refer to building names that are difficult for visitors to find.[3]

In 2010, Arlington County developed the Crystal City Sector Plan, which presented the community’s vision to transform Crystal City into a more inviting, lively and walkable community with more ground floor retail, better quality office space and more housing options. This 40-year plan won the American Planning Association’s 2013 National Planning Achievement Award for Innovation in Economic Planning and Development. It pioneers the use of economic analysis for planning purposes and is among the first of its kind to closely study the economics of demolishing and replacing major commercial buildings.

Economy

Crystal City currently has over 22,000 residents, while around 60,000 come to work there every weekday.[4] Once home to numerous Federal agencies, Crystal City’s claim to fame now is not just its prime location next to Reagan National Airport, the Pentagon and dozens of Arlington’s best eateries, but also as the place to be for thriving entrepreneurs.

It is home to the United States Marshals Service and numerous Department of Defense offices. It also has offices of numerous defense contractors, the General Services Administration, and many satellite offices for The Pentagon, especially during the Pentagon Renovation Program.[5] Pentagon offices in Crystal City include the headquarters of the Warrior Transition Command and the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction.

At one time US Airways had its headquarters in Crystal Park Four in Crystal City.[6] After US Airways merged with America West Airlines in 2005, the combined company closed the Virginia headquarters and moved the management to Tempe, Arizona, in Greater Phoenix.[7] Today, the Crystal City neighborhood is also home to headquarters for Lidl, Lyft, Bloomberg BNA and others.

Crystal City is home to several associations and technology companies, including Muscular Dystrophy Association, National Waste & Recycling Association, American Diabetes Association,[8] American Public Power Association, PBS,[9] and Consumer Technology Association[10] and more.

On November 13, 2018, Amazon.com announced that Arlington's Crystal City neighborhood would be the location of one of two campuses for its Amazon HQ2, with the other campus planned for Long Island City in Queens, New York City. Both campuses would have 25,000 workers.[11] [12][13][14] In Amazon's announcement, a joint press release was presented by the Northern Virginia bidders that Amazon's HQ2 neighborhood location would be jointly marketed as "National Landing", which encompasses not only Crystal City but also Pentagon City and Potomac Yard.[15] In February 2019, Amazon decided to cancel its plans for the Queens location for HQ2 and instead focus exclusively on the Crystal City/Pentagon City site. Construction is currently ongoing.

References

- "Envisioning Crystal City as part of a larger community". Greater Greater Washington. 2009-05-14. Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- "Crystal Underground opens," by Pat Royse, The Washington Post, Sep 30, 1976, p. VA_14.

- David A. Wheeler. "Crystal City Name Changes (Address Changes)". Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- Linda Wheeler (1995-03-25). "Crystal City: Model of Convenience". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- E.L. Wasson (2007-12-01). "Washington, D.C.: Threatened Crystal City closures appear derailed | The Real Deal | New York Real Estate News". Ny.therealdeal.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- "THE FOLLOWING LETTER WAS SENT TO THE ATTACHED LIST OF U.S. & FOREIGN AIRLINE, and TRAVEL AGENCY EXECUTIVES Archived 2013-02-18 at the Wayback Machine." U.S. Department of Transportation. July 14, 1995. Retrieved on March 1, 2010.

- "US Airways to move headquarters to Tempe, Ariz., early in 2006." The Tribune. July 23, 2005. Retrieved on March 1, 2010.

- Daniel J. Sernovitz (January 20, 2015). "American Diabetes Association to shift headquarters from Alexandria to Crystal City". Washington Business Journal.

- "The PBS No Downtime Move". Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "CTA - home". CTA. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- O'Connell, Jonathan; McCartney, Robert (November 5, 2018). "Amazon in advanced talks about putting HQ2 in Northern Virginia, those close to process say". Washington Post.

- "Amazon Selects New York City and Northern Virginia for New Headquarters". Amazon. November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- Stevens, Laura; Morris, Keiko; Honan, Katie (November 13, 2018). "Amazon Picks New York City, Northern Virginia for Its HQ2 Locations". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- "Amazon's Grand Search For 2nd Headquarters Ends With Split: NYC And D.C. Suburb". NPR.org. November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- "National Landing? Long Island City? This is where Amazon's headquarters are located". USA Today.

Further reading

- Silverman, Elissa (2005-06-06). "Crystal City Attempts to Change for The Better". The Washington Post. pp. D01. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- www.nytimes.com/2016/04/20/realestate/commercial/crystal-city-once-cast-off-by-washington-reboots-itself.html

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Arlington/Crystal City. |