Cullen House

Cullen House is a large house, now divided into fourteen separate dwellings, about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) south west of the coastal town of Cullen in Moray, Scotland. Originally built between 1600 and 1602, incorporating some of the fabric of a medieval building on the site, it was the seat of the Ogilvies of Findlater, who went on to become the Earls of Findlater and Seafield, and remained in their family until 1982. The house has been extended and remodelled several times since 1602, by prominent architects such as William Adam, his sons James and John Adam, and David Bryce. It has been described by the architectural historian Charles McKean as "one of the grandest houses in Scotland".

| Cullen House | |

|---|---|

Sep2006.jpg.webp) Cullen House, viewed from the west | |

Cullen House Location in Moray, Scotland | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Scottish Baronial Revival, with some older features remaining |

| Town or city | Cullen, Moray |

| Country | Scotland |

| Coordinates | 57°41′01″N 2°49′45″W |

| Construction started | 20 March 1600[1] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Various, including Alexander McGill, James Smith, William, James and John Adam, James Playfair, John Baxter, David Bryce, Robert Lorimer and Kit Martin[2] |

| Designations | Category A listed building[3] |

The house sits in an expansive estate, enlarged in the 1820s when the entire village of Cullen, save for Cullen Old Church, was demolished to make way for improvements to the grounds by Lewis Grant-Ogilvy, 5th Earl of Seafield. A new village, closer to the coast, was constructed for the inhabitants.

Cullen House was designated a Category A listed building in 1972, by which time it had fallen into a state of disrepair. Its contents were sold in 1975, and in 1982 it was purchased by Kit Martin, a specialist in saving historic buildings, who worked with the local architect Douglas Forrest to convert it into fourteen individual dwellings, while retaining much of the original interior of the building. The house was badly damaged by fire in 1987, and underwent an extensive programme of restoration that lasted until 1989.

Description

Cullen House is a large turreted house, ornately decorated and set on a clifftop above the Cullen Burn.[3] The structure started as an L-plan tower house, built between 1600 and 1602 and incorporating fabric from earlier buildings on the site, onto which wings have been added, extending to the north and south.[3][4] Built in various stages over several centuries, it is described by the architectural historian Charles McKean as an "enormously complicated structure", and "one of the grandest houses in Scotland".[1]

Exterior

The original entrance to the tower house is in the south-west angle of its west courtyard, in a single-bay, four-storey facade, beneath two tourelles supported by corbels, one of which bears the initials SVO and DMD, representing Sir Walter Ogilvy and his wife, Dame Margaret Drummond, for whom the house was built.[4] This entrance has now been blocked and replaced by a window.[3]

The earliest section of the north wing, of five bays and three storeys in height, extends to the left of the door. Built in the early seventeenth century, its roof was raised in the eighteenth, and its windows were replaced with larger sash and case windows in the Georgian style.[4] The roof line is broken by five elaborately carved dormerheads, and in the centre is another entrance, designed by David Bryce and carved by Thomas Goodwillie, featuring pilasters, much carved foliage, a heraldic plaque and a pair of sculptural lions rampant, which is described by architectural historians David Walker and Matthew Woodworth in their Pevsner guidebook on the region as "exuberant" and "wildly boisterous".[4] Beyond this block, there is a rectangular eighteenth-century extension, with a protruding gable end that was heavily Baronialized in the nineteenth century. This features two-storey tourelles on each corner, and numerous busts and carved figures, also by Goodwillie.[3][4]

The original seventeenth-century part of the west wing has seven bays, with three elaborate dormerheads; these are carved with figures that depict Faith, Hope, and another with a missing inscription. The original seventeenth-century windows were mostly replaced with larger ones in the eighteenth century, but some of the original ones were blocked and have been retained as decorative features. At the west end, there is another extension, which was also Baronialized in the nineteenth century, with more tourelles, a round staircase tower, and carvings of Father Time, depicted holding a scythe and flanked by figures representing Youth and Old Age.[4]

The house's east facade, again heavily Baronialized, has another entrance, recessed into the centre of the north wing, also with an elaborately carved doorway by Goodwillie; this is very similar to its counterpart on the other side of the wing, but without the lions.[4] To either side of the doorway are a pair of four-storey towers, one with a datestone showing 1668, and there is a square bartizan as well as three more triangular dormerheads. To the left side of the east facade is the rear of the original tower house, which has an early seventeenth-century tourelle, and another dormerhead featuring a carved sun.[4]

The south facade looks onto the clifftop and the Cullen Burn below. At its right end is a staircase tower attached to the original tower house, to the left of which is a very large bow window. Left of this is a section of five bays, which part of the eighteenth-century building work and has been little altered since, save for the addition of a single tourelle, and an elaborate staircase tower which can be seen prominently from the gorge below and is known as the Punch Bowl.[1][4]

Beyond the north wing is a U-plan service court, two storeys high with a bellcote on its north facade. Built in the late eighteenth century, it originally housed the kitchen and laundry, and has been converted into six apartments and an architectural studio.[1][4]

Interior

The main house has been divided into seven separate apartments, but each of the principal rooms has been preserved and many of its historical features remain intact. There is a square entrance hall in the north wing, with a fireplace decorated with blue and white Delftware tiles.[3][4] Beyond this is a two-storey stair hall, with a staircase and ceiling by James Adam, and an elaborately carved wooden door, dated 1618, with its original key and lock.[4] Many of the house's original public rooms retain original Victorian ceilings; others, which were damaged in the fire of 1987, have been restored or reproduced. A grand Jacobean painted ceiling, which was uncovered in 1880 but destroyed by the fire, has been replaced by a painting of bubbles and astronauts by Robert Ochardson.[4]

Grounds

Leading off the house's west courtyard is a bridge built between 1744 and 1745 by William Adam, which spans the gorge of the Cullen Burn. It has a single arch, with a span of 25.6 metres (84 ft) and a height of 19.5 metres (64 ft), and is built of granite ashlar with rubble spandrels.[4] The bridge is itself designated as a Category A listed building separate from the house.[5]

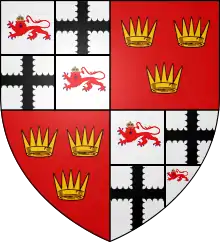

At the south-east entrance to the estate is a gatehouse known as the Grand Entrance, built by James Adam between 1767 and 1768. The wide entrance for carriages is built in the form of a triumphal arch, with ionic columns supporting a pediment with armorial decoration in the tympanum, and decorated with lions, rampant at the apex, and recumbent to the sides. There are entrances for pedestrians in the walls flanking the archway, which connect to a number of single-storey lodges.[1][4] This whole structure is also separately designated as a Category A listed building.[6]

Also within the grounds is a walled garden of 1788 designed by James Playfair. Near the coast there is a temple in the form of a rotunda supported by eight ionic columns, which originally had a statue depicting either Pomona or Pheme at its centre, all above a panelled room, which at one point was used as a tearoom; this was designed by Playfair in 1788, but constructed in 1822 by William Robertson. The floor to the rotunda has collapsed into the tearoom, which is now gutted; the plinth which supported the statue, which is now lost, lies in the centre of the room below the rotunda. This structure too is separately designated a Category A listed building.[1][4][7]

Robertson, and his nephews Alexander and William Reid (who continued his practice after his death), were responsible for a number of other estate buildings, including an ice house, a garden house, a laundry, and cottages for staff such as gardeners.[1][4]

History

Cullen House was built by the influential Ogilvies of Findlater, who had their seat at Findlater Castle.[1] Their parish church had traditionally been at Fordyce, but in 1482 the Ogilvies were granted the lands of Findochty and Seafield, and by 1543 they had changed their patronage to Cullen Old Church,[1] which they elevated to the status of a collegiate church. Buildings from around this time, which served as accommodation for the church's canons, stood on the site of the current house, and themselves probably incorporated some of the fabric of an earlier medieval building, known as Inverculain, which is mentioned in records of 1264.[4][8]

On 20 March 1600, work was started on a large new house for the laird, Sir Walter Ogilvy, and his wife Dame Margaret Drummond, initially built as an L-plan tower house, building upon some of the structure of the canons' lodgings.[1][4] The family continued to prosper: in 1616, Walter Ogilvy was created Lord Ogilvy of Deskford; his son James was further elevated to become the first Earl of Findlater in 1638; and in 1701 another James would become the Earl of Findlater and Seafield.[4]

In the centuries following its initial construction, the house underwent a series of renovations, extensions and modifications. A tower was added in 1660, shortly after the third Earl inherited it, then in 1709 Alexander McGill and James Smith were asked to submit plans for a complete remodelling in the Palladian style. These were drawn up, but in the end less radical extensions and modifications were executed to the north and west wings, between 1711 and 1714. James and John Adam worked on the house from 1767 to 1769, installing the main staircase and building the gatehouse, and John Baxter made more internal modifications, and built the large bow window in the east facade, between 1777 and 1778. In 1780, Robert Adam was commissioned by the fourth Earl to provide a design for an entirely new house; these were not carried out however; nor were Playfair's 1788 designs for an extensive remodelling in "the Saxon style", but Playfair's walled garden was constructed in the grounds in that year.[2][4]

Thomas White, a landscape architect from Nottinghamshire,[9] drew up plans for extensive landscaped gardens in 1789, although these were only partially executed.[4] Between 1820 and 1830, Lewis Grant-Ogilvy, 5th Earl of Seafield extended the gardens considerably by demolishing the entire village of Cullen, and building a new planned town for its inhabitants, laid out by George MacWilliam with alterations by Peter Brown and William Robertson, nearer the coast.[10][11] The only remaining building from the original village is Cullen Old Church.[10] Later in the nineteenth century, the Great North of Scotland Railway hoped to cut through the house's grounds, but the earl refused his permission, forcing the company to build a viaduct, 196 metres (643 ft) long and 24.8 metres (81.4 ft) high, through the town of Cullen itself; the line was eventually opened in 1886.[12]

The house's current Baronial Revival appearance is largely the result of the extensive remodelling that was carried out from 1858 to 1868 by David Bryce, who worked to homogenise the disparate styles of the different parts of the building, and redesigned much of the interior.[1] By the time Bryce had finished working on the house, it had a total of 386 rooms.[1]

Renovation work was carried out on the house in 1913 by Robert Lorimer.[2] In 1972 it was designated a Category A listed building,[3] but by then it had become dilapidated, and its contents were sold off in 1975.[4] In 1982, Kit Martin purchased the house from the 13th Earl with the intention of saving the building. He and the local architect Douglas Forest set about repairing the structure, and together they converted it into fourteen separate private homes.[4][13]

In 1987, the house was badly damaged by a fire in the south east corner and the west wing; restoration work was carried out, lasting until 1989, but certain original features such as the early seventeenth-century painted ceiling in the second salon were irreparably damaged.[4]

References

- McKean, Charles (1987). The District of Moray – An Illustrated Architectural Guide. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press and RIAC Publishing. pp. 133–135. ISBN 1-87319-048-4.

- "Cullen House and estate buildings". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Cullen House (Category A Listed Building) (LB2219)". Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Walker, David W.; Woodworth, Matthew (2015). The Buildings of Scotland – Aberdeenshire: North and Moray. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 523–527. ISBN 978-0-300-20428-5.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Cullen House Bridge over the Burn of Cullen (Category A Listed Building) (LB2220)". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Cullen House, Main Entrance, Gates and Gate Lodges (Category A Listed Building) (LB2227)". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Cullen House, Temple of Pomona (Category A Listed Building) (LB15520)". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Cullen House". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Shepherd, Ian (1996). Exploring Scotland's Heritage: Aberdeen and North-East Scotland (2 ed.). Edinburgh: HMSO. p. 69. ISBN 0-11-4952906.

- Walker, David W.; Woodworth, Matthew (2015). The Buildings of Scotland–Aberdeenshire: North and Moray. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-300-20428-5.

- "Cullen Auld Kirk, Old Cullen". Discover Cullen. Cullen Voluntary Tourist Initiative. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Shepherd, Ian (1996). Exploring Scotland's Heritage: Aberdeen and North-East Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO. p. 85. ISBN 0-11-4952906.

- "Opinion – Iain Rennie and Dr Jean Rennie v Cullen House Gardens Limited". Lands Tribunal for Scotland. Retrieved 17 October 2019.