Palladian architecture

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from and inspired by the designs of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is recognised as Palladian architecture today is an evolution of his original concepts. Palladio's work was strongly based on the symmetry, perspective, and values of the formal classical temple architecture of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. From the 17th century Palladio's interpretation of this classical architecture was adapted as the style known as "Palladianism". It continued to develop until the end of the 18th century.

In Britain, Palladianism was briefly in vogue during the 17th century, but its flowering was cut short by the onset of the English Civil War and the imposition of austerity which followed. In the early 18th century it returned to fashion, not only in England but also, directly influenced from Britain, in Prussia. Count Francesco Algarotti may have written to Lord Burlington from Berlin that he was recommending to Frederick the Great the adoption in Prussia of the architectural style Burlington had introduced in England,[1] but Knobelsdorff's opera house on the Unter den Linden boulevard, based on Campbell's Wanstead House, had been constructed from 1741. Later in the century, when the style was falling from favour in Europe, it had a surge in popularity throughout the British colonies in North America, highlighted by examples such as Drayton Hall in South Carolina, the Redwood Library in Newport, Rhode Island, the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City, the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis, Maryland and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and Poplar Forest in Virginia.[2]

The style continued to be utilized in Europe throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, where it was frequently employed in the design of public and municipal buildings. From the latter half of the 19th century it was rivalled by the Gothic revival in the English-speaking world, whose champions such as Augustus Pugin, remembering the origins of Palladianism in ancient temples, deemed it too pagan for Anglican and Anglo-Catholic worship.[3] However, as an architectural style it has continued to be popular and to evolve; its pediments, symmetry and proportions are clearly evident in the design of many modern buildings today.

Palladio's architecture

Buildings entirely designed by Palladio are all in Venice and the Veneto, with an especially rich grouping of palazzi in Vicenza. They include villas, and churches such as the Basilica del Redentore in Venice. In Palladio's architectural treatises he followed the principles defined by the Roman architect Vitruvius and his 15th-century disciple Leon Battista Alberti, who adhered to principles of classical Roman architecture based on mathematical proportions rather than the rich ornamental style also characteristic of the Renaissance.[4]

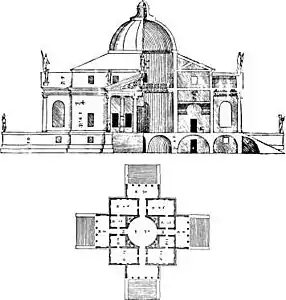

Palladio always designed his villas with reference to their setting. If on a hill, such as Villa Capra, facades were frequently designed to be of equal value so that occupants could have fine views in all directions. Also, in such cases porticos were built on all sides so that occupants could fully appreciate the countryside while being protected from the sun. Palladio sometimes used a loggia as an alternative to the portico. This can most simply be described as a recessed portico, or an internal single storey room, with pierced walls that are open to the elements. Occasionally a loggia would be placed at second floor level over the top of a loggia below, creating what was known as a double loggia. Loggias were sometimes given significance in a facade by being surmounted by a pediment. Villa Godi has as its focal point a loggia rather than a portico, plus loggias terminating each end of the main building.[5]

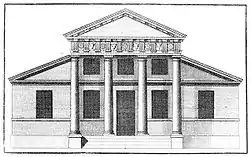

Palladio would often model his villa elevations on Roman temple facades. The temple influence, often in a cruciform design, later became a trademark of his work. Palladian villas are usually built with three floors: a rusticated basement or ground floor, containing the service and minor rooms. Above this, the piano nobile accessed through a portico reached by a flight of external steps, containing the principal reception and bedrooms, and above it is a low mezzanine floor with secondary bedrooms and accommodation. The proportions of each room within the villa were calculated on simple mathematical ratios like 3:4 and 4:5, and the different rooms within the house were interrelated by these ratios. Earlier architects had used these formulas for balancing a single symmetrical facade; however, Palladio's designs related to the whole, usually square, villa.[5]

Palladio deeply considered the dual purpose of his villas as both farmhouses and palatial weekend retreats for wealthy merchant owners. These symmetrical temple-like houses often have equally symmetrical, but low, wings sweeping away from them to accommodate horses, farm animals, and agricultural stores. The wings, sometimes detached and connected to the villa by colonnades, were designed not only to be functional but also to complement and accentuate the villa. They were, however, in no way intended to be part of the main house, and it is the design and use of these wings that Palladio's followers in the 18th century adapted to become an integral part of the building.[6]

Palladio's The Four Books of Architecture was first published in 1570, This architectural treatise contains descriptions and illustrations of his own architecture along with the Roman building that inspired him to create the style.[7] Palladio reinterpreted Rome's ancient architecture and applied it to all kinds of buildings from grand villas and public buildings to humble houses and farm sheds.[8]

The Venetian and Palladian windows

The Palladian, Serlian, or Venetian window features largely in Palladio's work and is almost a trademark of his early career. There are two different versions of the motif: properly the simpler one is called a Venetian window, and a more elaborate and specific one a Palladian window or "Palladian motif", although this distinction is not always observed.

The Venetian window has three parts: a central high round-arched opening, with two smaller rectangular openings to the sides, the latter topped by lintels and supported by columns.[9] This really goes back to the ancient Roman triumphal arch, and was first used outside Venice by Donato Bramante[10] and later mentioned by Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) in his seven-volume architectural book Tutte l'opere d'architettura et prospetiva expounding the ideals of Vitruvius and Roman architecture. It can be used in series, but is often only used once in a facade, as at New Wardour Castle, or once at each end, as on the inner facade of Burlington House (true Palladian windows).

Palladio's elaboration of this, normally used in a series, places a larger or giant order in between each window, and doubles the small columns supporting the side lintels, placing the second column behind rather than beside the first. This was in fact introduced in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice by Jacopo Sansovino (1537), and heavily used by Palladio in the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza,[11] where it is used on both storeys; this feature was less often copied. Here the openings are not strictly windows, as they enclose a loggia. Pilasters might replace columns, as in other contexts. Sir John Summerson suggests that the omission of the doubled columns may be allowed, but the term "Palladian motif" should be confined to cases where the larger order is present.[12]

Palladio used these elements extensively, for example in very simple form in his entrance to Villa Forni Cerato. It is perhaps this extensive use of the motif in the Veneto that has given the window its alternative name of the Venetian window; it is also known as a Serlian window. Whatever the name or the origin, this form of window has probably become one of the most enduring features of Palladio's work seen in the later architectural styles evolved from Palladianism.[13] According to James Lees-Milne, its first appearance in Britain was in the remodeled wings of Burlington House, London, where the immediate source was actually in Inigo Jones's designs for Whitehall Palace rather than drawn from Palladio himself.[14]

A variant, in which the motif is enclosed within a relieving blind arch that unifies the motif, is not Palladian, though Lord Burlington seems to have assumed it was so, in using a drawing in his possession showing three such features in a plain wall. Modern scholarship attributes the drawing to Vincenzo Scamozzi. Burlington employed the motif in 1721 for an elevation of Tottenham Park in Savernake Forest for his brother-in-law Lord Bruce (since remodeled). Kent picked it up in his designs for the Houses of Parliament, and it appears in Kent's executed designs for the north front of Holkham Hall.[15]

Early Palladianism

In 1570 Palladio published his book, I quattro libri dell'architettura, which inspired architects across Europe.

During the 17th century, many architects studying in Italy learned of Palladio's work. Foreign architects then returned home and adapted Palladio's style to suit various climates, topographies and personal tastes of their clients. Isolated forms of Palladianism throughout the world were brought about in this way. However, the Palladian style did not reach the zenith of its popularity until the 18th century, primarily in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and later North America.[16] In Venice itself there was an early reaction to the excesses of Baroque architecture that manifested itself as a return to Palladian principles. The earliest neo-Palladians there were the exact contemporaries, both trained up as masons, Domenico Rossi (1657–1737)[17] and Andrea Tirali (1657–1737).[18] Tommaso Temanza, their biographer, proved to be the movement's most able and learned proponent; in his hands the visual inheritance of Palladio's example became increasingly codified in correct rules and drifted towards neoclassicism.[19]

The most influential follower of Palladio anywhere, however, was the Englishman Inigo Jones, who travelled throughout Italy with the 'Collector' Earl of Arundel, annotating his copy of Palladio's treatise, in 1613–14.[20] The "Palladianism" of Jones and his contemporaries and later followers was a style largely of facades, and the mathematical formulae dictating layout were not strictly applied. A handful of great country houses in England built between 1640 and 1680, such as Wilton House, are in this Palladian style. These follow the great success of Jones' Palladian designs for the Queen's House at Greenwich and the Banqueting House at Whitehall, the uncompleted royal palace in London of King Charles I.[21]

However, the Palladian designs advocated by Inigo Jones were too closely associated with the court of Charles I to survive the turmoil of the English Civil War. Following the Stuart restoration, Jones's Palladianism was eclipsed by the Baroque designs of such architects as William Talman and Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor, and even Jones' pupil John Webb.[22]

Neo-Palladian

English Palladian architecture

The Baroque style, popular in continental Europe, was never truly to the English taste and was considered excessively flamboyant, Catholic and 'florid'. It was quickly superseded when, in the first quarter of the 18th century, four books were published in Britain which highlighted the simplicity and purity of classical architecture. These were:

- Vitruvius Britannicus, published by Colen Campbell in 1715 (of which supplemental volumes appeared through the century),

- Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura, translated by Giacomo Leoni and published from 1715 onwards,

- Leon Battista Alberti's De re aedificatoria, translated by Giacomo Leoni and published 1726,

- The Designs of Inigo Jones... with Some Additional Designs, published by William Kent, 2 vols., 1727 (A further volume, Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. William Kent was published in 1744 by the architect John Vardy, an associate of Kent.)

The most favoured of these among the wealthy patrons of the day was the four-volume Vitruvius Britannicus by Colen Campbell. Campbell was both an architect and a publisher. It was essentially a book of design containing architectural prints of British buildings, which had been inspired by the great architects from Vitruvius to Palladio; at first mainly those of Inigo Jones, but the later works contained drawings and plans by Campbell and other 18th-century architects. These four books greatly contributed to Palladian architecture becoming established in 18th-century Britain. Their authors became the most fashionable and sought after architects of the era. Due to his book Vitruvius Britannicus, Colen Campbell was chosen as the architect for banker Henry Hoare I's Stourhead house, a masterpiece that became the inspiration for dozens of similar houses across England.

At the forefront of the new school of design was the aristocratic "architect earl", Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. In 1729, he and William Kent, designed Chiswick House. This House was a reinterpretation of Palladio's Villa Capra, but purified of 16th century elements and ornament. This severe lack of ornamentation was to be a feature of the English Palladianism. In 1734 William Kent and Lord Burlington designed one of England's finest examples of Palladian architecture with Holkham Hall in Norfolk. The main block of this house followed Palladio's dictates quite closely, but Palladio's low, often detached, wings of farm buildings were elevated in significance. Kent attached them to the design, banished the farm animals, and elevated the wings to almost the same importance as the house itself. These wings were often adorned with porticos and pediments, often resembling, as at the much later Kedleston Hall, small country houses in their own right. It was the development of the flanking wings that was to cause English Palladianism to evolve from being a pastiche of Palladio's original work.

Architectural styles evolve and change to suit the requirements of each individual client. When in 1746 the Duke of Bedford decided to rebuild Woburn Abbey, he chose the Palladian style for the design, as this was now the most fashionable of the era. He selected architect Henry Flitcroft, a protégé of Burlington. Flitcroft's designs, while Palladian in nature, would not be recognised by Palladio himself. The central block is small, only three bays, the temple-like portico is merely suggested, and it is closed. Two great flanking wings containing a vast suite of state rooms replace the walls or colonnades which should have connected to the farm buildings; the farm buildings terminating the structure are elevated in height to match the central block and given Palladian windows, to ensure they are seen as of Palladian design. This development of the style was to be repeated in countless houses and town halls in Britain over one hundred years. Falling from favour during the Victorian era, it was revived by Sir Aston Webb for his refacing of Buckingham Palace in 1913. Often the terminating blocks would have blind porticos and pilasters themselves, competing for attention with, or complementing the central block. This was all very far removed from the designs of Palladio two hundred years earlier.

English Palladian houses were now no longer the small but exquisite weekend retreats from which their Italian counterparts were conceived. They were no longer villas but "power houses" in Sir John Summerson's term, the symbolic centres of power of the Whig "squirearchy" that ruled Britain. As the Palladian style swept Britain, all thoughts of mathematical proportion were swept away. Rather than square houses with supporting wings, these buildings had the length of the façade as their major consideration: long houses often only one room deep were deliberately deceitful in giving a false impression of size.

Irish Palladianism

During the Palladian revival period in Ireland, even quite modest mansions were cast in a neo-Palladian mould. Palladian architecture in Ireland subtly differs from that in England. While adhering as in other countries to the basic ideals of Palladio, it is often truer to them – perhaps because it was often designed by architects who had come directly from mainland Europe, and therefore were not influenced by the evolution that Palladianism was undergoing in Britain. Whatever the reason, Palladianism still had to be adapted for the wetter, colder weather.

One of the most pioneering Irish architects was Sir Edward Lovett Pearce (1699–1733), who became one of the leading advocates of Palladianism in Ireland. A cousin of Sir John Vanbrugh, he was originally one of his pupils, but rejecting the Baroque style, he spent three years studying architecture in France and Italy, before returning home to Ireland. His most important Palladian work is the former Irish Houses of Parliament in Dublin. He was a prolific architect who also designed the south façade of Drumcondra House in 1725 and Summerhill House in 1731, which was completed after Pearce's death by Richard Cassels.[24]

Pearce oversaw the building of Castletown House, near Dublin, designed by the Italian architect Alessandro Galilei (1691–1737). It is perhaps the only Palladian house in Ireland to have been built with Palladio's mathematical ratios, and one of the three Irish mansions which claim to have inspired the design of the White House in Washington.

Other examples include Russborough, designed by Cassels, who also designed the Palladian Rotunda Hospital in Dublin and Florence Court in County Fermanagh. Irish Palladian country houses often feature robust Rococo plasterwork, frequently executed by the Lafranchini brothers, an Irish specialty, which is far more flamboyant than the interiors of their contemporaries in England. So much of Dublin was built in the 18th century that it set a Georgian stamp on the city; however arising out of bad planning and poverty, until recently Dublin was one of the few cities where fine 18th-century housing could be seen in ruinous condition. Elsewhere in Ireland after 1922, the lead was removed from the roofs of unoccupied Palladian houses for its value as scrap, with the houses often abandoned owing to excessive roof-rate based taxes. Some roofless Palladian houses can still be found in the depopulated Irish countryside.

North American Palladianism

Palladio's influence in North America[25] is evident almost from the beginning of architect-designed building there, though the Irish philosopher George Berkeley may have been America's pioneering Palladian. Acquiring a large farmhouse in Middletown, near Newport in the late 1720s, Berkeley dubbed it "Whitehall" and improved it with a Palladian doorcase derived from William Kent's Designs of Inigo Jones (1727), which he may have brought with him from London.[26] Palladio's work was included in the library of a thousand volumes he amassed for the purpose and sent to Yale College.[27] In 1749, Peter Harrison adopted the design of his Redwood Library in Newport, Rhode Island, more directly from Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura, while his Brick Market, also in Newport, of a decade later is also Palladian in conception.[28]

The Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis, Maryland (illustration) is an example of Palladian architecture in the United States. It is the only existing work of colonial academic architecture that was principally designed from a plate in Palladio's Quattro libri. The house was designed by the architect William Buckland in 1773–74 for wealthy farmer Matthias Hammond of Anne Arundel County, Maryland. It was modeled on the design of the Villa Pisani in Montagnana, Italy in Book II, Chapter XIV of I quattro libri dell’achitettura.

The politician and architect Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) once referred to Palladio's Quattro libri as his bible. Jefferson acquired an intense appreciation of Palladio's architectural concepts, and his designs for his own beloved Monticello,[29] the James Barbour Barboursville estate, Virginia State Capitol, and the University of Virginia were based on drawings from Palladio's book.[30] Realizing the powerful political significance pertaining to ancient Roman buildings, Jefferson designed his civic buildings in the Palladian style. Monticello (remodelled between 1796 and 1808) is quite clearly based on Palladio's Villa Capra, however, with modifications, in a style which is described in America today as Colonial Georgian. Jefferson's Pantheon or Rotunda at the University of Virginia is undeniably Palladian in concept and style.[31]

.jpg.webp)

In Virginia and Carolina, the Palladian manner is epitomised in numerous Tidewater plantation houses, such as Stratford Hall or Westover Plantation, or Drayton Hall near Charleston. These examples are all classic American colonial examples of a Palladian taste that was transmitted through engravings, for the benefit of masons—and patrons, too—who had no first-hand experience of European building practice. A feature of American Palladianism was the re-emergence of the great portico which, again, as in Italy, fulfilled the need of protection from the sun; the portico in various forms and size became a dominant feature of American colonial architecture. In the north European countries the portico had become a mere symbol, often closed, or merely hinted at in the design by pilasters, and sometimes in very late examples of English Palladianism adapted to become a porte-cochère; in America, the Palladian portico regained its full glory.

One house which clearly shows this Palladian-Gibbs influence is Mount Airy, in Richmond County, Virginia, built in 1758–62.[32]

At Westover the north and south entrances, made of imported Portland stone, were patterned after a plate in William Salmon's Palladio Londinensis (1734).[33]

The distinctive feature of Drayton Hall, its two-storey portico, was derived directly from Palladio.[34]

The neoclassical presidential mansion, the White House in Washington, was inspired by Irish Palladianism. Both Castle Coole and Richard Cassel's Leinster House in Dublin claim to have inspired the architect James Hoban, who designed the executive mansion, built between 1792 and 1800. Hoban, born in Callan, County Kilkenny, in 1762, studied architecture in Dublin, where Leinster House (built c. 1747) was one of the finest buildings at the time. The White House is more neoclassical than Palladian, particularly the South façade, which closely resembles James Wyatt's 1790 design for Castle Coole, also in Ireland. Castle Coole is, in the words of the architectural commentator Gervase Jackson-Stops, "A culmination of the Palladian traditions, yet strictly neoclassical in its chaste ornament and noble austerity."[35]

One of the adaptations made to Palladianism in America was that the piano nobile, now tended to be placed on the ground floor rather than above a service floor, as was the tradition in Europe. This service floor, if it existed at all, was now a discreet semi-basement. This negated the need for an ornate external staircase leading to the main entrance as in the more original Palladian designs. This would also be a feature of the neoclassical style that followed Palladianism.

.jpg.webp)

The only two houses in the United States from the English colonial period (1607–1776) that can be definitively attributed to designs from I quattro libri dell'architettura are architect William Buckland's Hammond-Harwood House (1774) in Annapolis, Maryland and Thomas Jefferson's first Monticello. The design source for the Hammond-Harwood House is Villa Pisani, Montagnana (Book II, Chapter XIV), and for the first Monticello (1770) the design source is Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese (Book II, Chapter XIV). Thomas Jefferson later covered this façade with additions so that the Hammond-Harwood House remains the only pure and pristine example of direct modeling in America today.[36]

Because of its later development, Palladian architecture in Canada is rare. One notable example is the Nova Scotia Legislature building, completed in 1819. Another example is Government House in St. John's, Newfoundland.

The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., a non-profit membership organization, was founded in 1979 to research and promote understanding of Palladio's influence in the United States.[37]

Legacy

By the 1770s in Britain, such architects as Robert Adam and Sir William Chambers were in huge popular demand, but they were now drawing on a great variety of classical sources, including ancient Greece, so much so that their forms of architecture were eventually defined as neoclassical rather than Palladian. In Europe, the Palladian revival ended by the end of the 18th century. In North America, Palladianism lingered a little longer; Thomas Jefferson's floor plans and elevations owe a great deal to Palladio's Quattro libri. The term "Palladian" today is often misused, and tends to describe a building with any classical pretensions. There was, however, a revival of Palladian ideas amongst the colonial revivalists of the early 20th century, and the strain has been unbroken, even through the modernist period.

In the mid-20th century, the originality of the approach of the architectural historian Colin Rowe had the effect of re-situating the assessment of modern architecture within history and acknowledged the Palladian architecture as an active influence. In the later 20th century, when Rowe's influence had spread worldwide, this approach had become a key element in the process of architectural and urban design. If "the presence of the past" was evident in the work of many architects in the late 20th century, from James Stirling to Aldo Rossi, Robert Venturi, Oswald Matthias Ungers, Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves and others, this was largely due to the influence of Rowe. Colin Rowe's unorthodox and non-chronological view of history then made it possible for him to develop theoretical formulations such as his famous essay "The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa" (1947) in which he theorised that there were compositional "rules" in Palladio's villas that could be demonstrated to correspond to similar "rules" in Le Corbusier's villas at Poissy and Garches.[38] This approach enabled Rowe to elaborate an astonishingly fresh and provocative trans-historical assessment of both Palladio and Le Corbusier, in which the architecture of both was assessed not in chronological time, but side by side in the present moment.[38]

See also

Notes

- James Lees-Milne, The Earls of Creation 1962:120.

- The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., "Palladio and English-American Palladianism." Archived 2009-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Frampton, p. 36

- Copplestone, p.250

- Copplestone, p.251

- Copplestone, pp.251–252

- webmaster@vam.ac.uk, Victoria and Albert Museum, Digital Media. "Style Guide: Palladianism". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- Kerley, Paul (2015-09-10). "Palladio: The architect who inspired our love of columns". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- Summerson, 134

- Ackerman, Jaaes S. (1994). Palladio (series "Architect and Society")

- Summerson, 129-130

- Summerson, 130

- Andrea Palladio, Caroline Constant. The Palladio Guide. Princeton Architectural Press, 1993. p. 42.

- "The earliest example of the revived Venetian window in England", Lees-Milne, The Earls of Creation, 1962:100.

- James Lees-Milne 1962:133f.

- Copplestone, p.252

- Rossi built the new façade for the rebuilt Sant'Eustachio, known in Venice as San Stae, 1709, which was among the most sober in a competition that was commemorated with engravings of the submitted designs, and he rebuilt Ca' Corner della Regina, 1724–27 (Deborah Howard and Sarah Quill, The Architectural history of Venice, 2002: 238f).

- His façade of San Vidal is a faithful restatement of Palladio's San Francesco della Vigna and his masterwork is Tolentini, Venice, 1706–14 (Howard and Quill 2002)

- Robert Tavernor, Palladio and Palladianism Thames & Hudson, 1991:112.

- Hanno-Walter Kruft. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Princeton Architectural Press, 1994 and Edward Chaney, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook, 2006).

- Copplestone, p.280

- Copplestone, p.281

- "Andrea Palladio 1508–1580". Irish Architectural Archive. 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Sheridan, Pat (2014). "Sir Edward Lovett Pearce 1699–1733: the Palladian architect and his buildings". Dublin Historical Record. 67 (2): 19–25. JSTOR 24615990.

- A brief survey is Robert Tavernor, "Anglo-Palladianism and the birth of a new nation" in Palladio and Palladianism, 1991:181–209; Walter M. Whitehill, Palladio in America, 1978 is still the standard work.

- Edwin Gaustad, George Berkeley in America (Yale University Press, 1979): "Berkeley's one architectural achievement in the New World" (p. 70).

- Gaustad, p. 86.

- The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., "Building America." Archived 2009-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Fiske Kimball, Thomas Jefferson, Architect, 1916.

- Frederick Nichols, Thomas Jefferson's Architectural Drawings, 1984.

- Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed (1980). Palladio's Architecture and Its Influence: A Photographic Guide. Dover Publications. p. 107. ISBN 0-486-23922-5.

- Roth, Leland M., A Concise History of American Architecture, Harper & Row, Publishers, NY, 1980

- Severens, Kenneth, Southern Architecture: 350 Years of Distinctive American Buildings, E.P. Dutton, NY 1981 p 37; specifically, both doors seem to have been derived from plates XXV and XXVI of Palladio Londinensis, a builders guide first published in London in 1734, the very year when the doorways may have been installed. (Morrison, High, American's First Architecture: From the First Colonial Settlements to the National Period. Oxford University Press, NY 1952 p. 340).

- Severens, Kenneth, Southern Architecture: 350 Years of Distinctive American Buildings, E.P. Dutton, NY 1981 p 38

- Jackson-Stops p. 106

- "The Palladian Connection". Hammond-Harwood House Association. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "About – Center for Palladian Studies in America". Palladian Studies. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays, MIT Press, Main essay reprinted in collected works volume, (1976).

References

- Ackerman, Jaaes S. (1994). Palladio (series "Architect and Society").

- Chaney, Edward (2006). "George Berkeley's Grand Tours: The Immaterialist as Connoisseur of Art and Architecture", in The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations Since the Renaissance (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4474-9.

- Copplestone, Trewin (1963). World Architecture. Hamlyn.

- Dal Lago, Adalbert (1966). Ville Antiche. Milan: Fratelli Fabbri.

- Frampton, Kenneth. (2001). Studies in Tectonic Culture. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56149-2.

- Halliday, E" E. (1967). Cultural History of England. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. Pavilion Books Ltd.

- Kostof, Spiro. A History of Architecture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, Hilary, and John O'Connor (1994). Philip Johnson: The architect in His Own Words. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

- Marten Paolo (1993). Palladio. Koln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH. (Photos of Palladio's surviving buildings)

- Reed, Henry Hope, and Joseph C. Farber (1980). Palladio's Architecture and Its Influence. New York: Dover Publications.

- Ruhl, Carsten (2011). Palladianism: From the Italian Villa to International Architecture, European History Online. Mainz: Institute of European History. Retrieved: May 23, 2011.

- Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- Tavernor, Robert (1979). Palladio and Palladianism (series "World of Art").

- Watkin, David (1979). English Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Wittkower, Rudolf. Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palladian architecture. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Palladian. |

- Chiswick House

- Holkham Hall

- (in English and Italian) International centre for the study of the architecture of Andrea Palladio (CISA)

- Palladian Architecture in England

- The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc.

- Palladio's Villas

- Thomas Jefferson's architecture

- Woburn Abbey

- Wallington Hall – National Trust

- The Palladian Way long distance walk

- "Palladianism Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-07-17.