Cultivation theory

Cultivation theory is a sociological and communications framework; it suggests that people who are regularly exposed to media over long periods of time are more likely to perceive the world's social realities as they are presented by the media they consume, which in turn affects their attitudes and behaviors.[2]

Cultivation theory was first advanced by professor George Gerbner in the 1960s[3]; it was later expanded upon by Gerbner and Larry Gross.[4] Cultivation theory began as a way to test the impact of television on viewers, especially how the exposure to violence through television affects human beings.[5] According to the theory's key proposition, "the more time people spend 'living' in the television world, the more likely they are to believe social reality aligns with reality portrayed on television."[6] Because cultivation theory assumes the existence of objective reality and value-neutral research, it can be categorized as part of positivistic philosophy.[7]

In practice, images and ideological messages transmitted by popular media heavily influence perceptions of the real world. The more media people consume, the more their perceptions change.[citation needed] Such images and messages, especially when repeated, help bring about the culture that it portrays. Cultivation theory aims to understand how long-term exposure to television programming, with its recurrent patterns of messages and images, can contribute to shared assumptions about the world.[citation needed]

In a 2004 study surveying almost 2,000 articles published in the top three mass communication journals since 1956, Jennings Bryant and Dorina Miron found that cultivation theory was the third most frequently utilized cultural theory.[8]

Definition

As defined by George Gerbner, cultivation is a way of thinking about media effects.[citation needed] Cultivation theory suggests that exposure to media over time subtly cultivates viewers' perceptions of reality.[citation needed] This theory is one of the most widely-known and influential approaches to studying the consequences of television's presence in our daily lives. In his analysis of cultivation, Gerbner draws attention to three entities: institutions, messages, and publics.[9]

Initial research on Cultivation theory shows that concerns regarding the effects of television on audiences stem from the unprecedented centrality of television in American culture.[6] Gerbner posited that television, as a mass medium of communication, had coalesced into a common symbolic environment.[citation needed] Television, Gerbner suggested, binds diverse communities together by socializing people into standardized roles and behaviors; thus television functions as part of the enculturation process.[10][11] He compared television's power in the modern world to that of religion in earlier times.[citation needed] Although violence was a special concern in some of his work, Gerbner's research focused on the larger meaning of heavy television consumption instead of the meaning behind specific messages.[12]

Though most researchers tend to focus on television as it is the most common form of media consumption in the world, cultivation theory has been applied to analyze many different forms of media, such as newspapers, film, and even photographs. Its framework is applicable whenever social observation occurs outside a natural environment.[13]

Background

Cultural Indicators Project

The cultivation theory arose from one of George Gerbner's research projects, the Cultural Indicators Project (CIP).[citation needed]

In 1968, the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence was formed to address issues regarding violence in American culture, including racial injustice culminating in the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, as well as the assassinations of Robert and John F. Kennedy.[citation needed] In short, America was experiencing a hostile climate of violence that was broadcast on television nationwide, generating many public opinions.[14] As a result, one specific area of interest for the administration of Lyndon Johnson was the effect of television violence on audiences. The CIP accordingly began as a stand-alone study commissioned for the National Violence Commission.[10]

Gerbner subsequently began work on the federally funded project at the Annenberg School of Communications.[15] Given the increasing divide between political conservatives and private commercial investors in the late 1960s, the CIP benefited as a middleman project. He and his team acted as impartial researchers examining the effects of television consumption without having any vested political or financial interest in its outcome.[16] As such, he had access to numerous grants that continued to fund the Cultural Indicators Project throughout the 1970s.[10]

In 1972, Congress facilitated the creation of the Surgeon General's Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior, which funded many studies including the CIP.[citation needed] Gerbner introduced the Violence Index, a yearly content analysis of prime time television that would show how violence was portrayed from season to season.[citation needed] The index allowed viewers access to data regarding the frequency of violence in shows but also raised questions regarding its accuracy and the hypotheses used. While the Violence Index received criticism, Gerbner and his team updated the index to ensure that the data being produced was accurately composed and addressed any criticisms. Gerbner's research found that violence was portrayed in prime time more frequently than in reality.[17]

Assumptions

Cultivation theory is based on three core assumptions:

Medium

The first assumption is that television is fundamentally different from other forms of mass media.[18]

Television is both visual and auditory and therefore does not require viewers to be literate. It has the potential to be free of charge aside from the initial cost of equipment (although free access to television is generally quite limited). There are multiple added costs for viewing, including the necessity of a converter box and high monthly fees for cable television. These expenses may prohibit low-income families from viewing television, however television is still universal as anyone can use it.

Television has a lower threshold for consumption than print media because of the need for literacy, and film because it requires a level of financial capability.[7] Since it is accessible and available to everyone, television is the “central cultural arm” of society."[18] Moreover, television could put dissimilar groups together, making them forget their differences for a time by providing them with a common experience.[5]

Television programming uses storytelling and engaging narratives to capture people's attention. Comparing how religion or education had previously been greater influences on social trends, Gerbner, Larry Gross, Michael Morgan, and Nancy Signorielli argue:

Television is the source of the most broadly shared images and messages in history... Television cultivates from infancy the very predispositions and preferences that used to be acquired from other primary sources ... The repetitive pattern of television's mass-produced messages and images forms the mainstream of a common symbolic environment.[10]

Audience

The second assumption is that television shapes society’s way of thinking and relating.[5]

Cultivation theory does not predict what people will do after watching a violent program but rather posits a connection between people's fears of a violence-filled world and their exposure to violent programming. The exposure to violent programming leads to what Gerbner calls the Mean World Syndrome, the idea that long-term exposure to violent media will lead to a distorted view that the world is more violent than it is.[citation needed]

Gerbner and Gross write that, "the substance of the consciousness cultivated by TV is not so many specific attitudes and opinions as more basic assumptions about the facts of life and standards of judgment on which conclusions are based."[19] Simply put, the realities created by television are not based on facts but speculation. According to James Shanahan and Vicki Jones, "[t]elevision is the dominant medium for distributing messages from cultural, social, and economic elites. Cultivation is more than just an analysis of effects from a specific medium; it is an analysis of the institution of television and its social role."[20]

Gerbner observed that television reaches people generally more than seven hours a day and offers "a centralized system of storytelling."[21] He asserts that television's major cultural functions are to stabilize social patterns and cultivate resistance to change. People live in terms of the stories they tell, and television tells these stories through news, drama, and advertising to almost everybody most of the time.[18]

Function and effect

The final assumption is that television's effects are limited. This assumption paradoxically asserts that it is a part of a larger sociocultural system. Therefore, although the effects of watching television may increase or decrease at any point in time, its effect is consistently present.[18]

Gerbner has explained this through an analogy of an ice age:

[J]ust as an average temperature shift of a few degrees can lead to an ice age or the outcomes of elections can be determined by slight margins, so too can a relatively small but pervasive influence make a crucial difference. The size of an effect is far less critical than the direction of its steady contribution.[22]

Rather than focus on the total impact of violent television, this analogy focuses more on the fact that there once was or is an impact to viewers just through exposure. Gerbner argues that watching television does not cause a particular behavior, but watching television over time adds up to our perception of the world around us.[17]

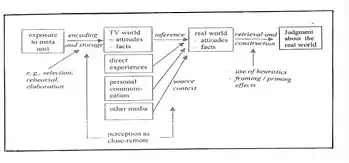

Research strategy analyzing the role of the media

Looking at the effects of television on society can be conducted through a four-part process:[9]

Message system analysis

Message system analysis is the first of this four-part cultivation theory-style research.[citation needed] This part has been used since 1967 to track the most stable and recurrent images in media content. Described by Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, and Signorielli as a "tool for making systematic, reliable, and cumulative observations about television content," it not only tracks the perceived awareness of an individual about what is viewed but it also represents the ongoing collective messages that shape larger community impressions over an extended period of time. Although the information provided through media channels is not always reliable, message system analysis provides a method for characterizing the transmitted messages.[10]

On the basis of message system analyses, "cultivation researchers develop hypotheses about what people would think about various aspects of reality if everything they knew about some issue or phenomenon were derived from television's dominant portrayals."[9] This step entails creating a detailed content analysis on the consistent images, themes, and messages in a particular show.

Another facet of the message system analysis discovered by Gerbner was described by Griffin (2012) as "equal violence, unequal risk." The research Gerbner conducted showed that the amount of violence portrayed in media stayed consistent but the distribution of that violence was never equal. Children and the elderly, for example, are more common recipients of violence than young or middle-aged adults. Gerbner often discovered trends in violence toward minority groups with African Americans and Hispanics receiving violence more often than Caucasians; two other demographics that experienced similar inequality were women and blue collar workers. "The ironic result of this tendency," Griffin writes, "is that the demographics showed, inaccurately, to be more in danger of violence than the rest are the demographics that will walk away from the media more afraid of violence."[11]

Questions

The second part of this process involves posing questions with the goal of learning about viewers' social realities.[citation needed] Findings from the message system analysis process guide researchers to formulate questions about social reality; these questions are posed to subjects in a study.[19] These question in these studies focus on people's feelings about their day-to-day lives with the hope of gaining a larger understanding of how they perceive their realities.[19]

Surveying

The third part brings step two into action: asking audience participants questions about their understanding of their lives and then surveying television consumption levels.[citation needed] After questions are formulated based on social reality, Gerbner and Gross explain that "[t]o each of these questions there is a 'television answer,' which is like the way things appear in the world of television, and another and different answer which is biased in the opposite direction, closer to the way things are in the observable world."[19]

These questions are then used to evaluate the detailed characteristics of the participants under evaluation. Measurement items include the breadth of television consumption, associated habitual behaviors, and the social, economic, and political makeup of the participants.[citation needed]

Cultivation differential

The final part of this process is cultivation differential, which can be described as "the percentage of difference in response between light and heavy television viewers."[11][17] Certain measures are evaluated, including sex, age, and education.

Gerbner and Gross state that the "margin of heavy viewers over light viewers giving the 'television answers' within and across groups is the 'cultivation differential' indicating conceptions about the social reality that viewing tends to cultivate."[19] Cultivation, according to Griffin, "deals with how TV's content might affect viewers—particularly the viewers who spend lots of time glued to the tube. This is where most of the action takes place in the theory."[11]

He found that the effect of television on its viewers is not unidirectional:

[U]se of the term 'cultivation' for television's contribution to the conception of social reality...[does not] necessarily imply a one-way, monolithic process. The effects of a pervasive medium upon the composition and structure of the symbolic environment are subtle, complex, and intermingled with other influences. This perspective, therefore, assumes an interaction between the medium and its publics.[10]

This cultivation differential is what he sought to discover in his research, seeking to find how often individuals who watched a significant amount of television were influenced by what they saw in the media. He believed there was no before-television stage in a person's life, alleging that the media influences a person the moment they are born. He focused on four attitudes: (1) the chance of involvement with violence, (2) the fear of walking alone at night, (3) perceived activity of the police, and (4) general mistrust of people.[11] When a person watches more television, that person is more likely to think he or she has a higher chance of being involved in violence and is more distrustful of others.[citation needed]

Key terms in cultivation analysis

Two types of cultivation

The process of cultivation that television contributes to viewers’ conceptions of social reality occurs in two ways:

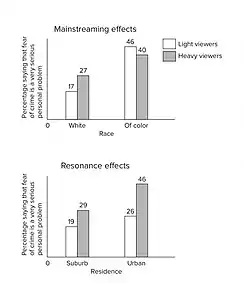

Mainstreaming

Mainstreaming is the process by which heavy TV viewers from disparate groups develop a common outlook on the world through constant exposure to the same images and labels:[11][24]

- blurring refers to the fusion of traditional distinctions,

- blending refers to the emergence of new conceptions into television's cultural mainstream, and

- bending refers to shifting the mainstream to the institutional interests of the medium and its sponsors.[24]

Mainstreaming through television plays a central role in society. There are many people who do not have access to television but its reach is so expansive that it has become the primary means responsible for shaping what is mainstream in our culture.[11] The mainstream is more than the sum of all cross- and sub currents; it represents the broadest range of shared meanings and assumptions in the most general, functional, and stable way.[25] Heavy viewing may override individual differences and perspectives, creating more of an American (and increasingly global) melting pot of social, cultural, and political ideologies.[25]

Gerbner found that ideas and opinions commonly held by heavy viewers as a result of mainstreaming pertain to politics and economics. According to Griffin (2012), Gerbner's research led to the conclusion that heavy viewers tend to label themselves as middle-class citizens who are politically moderate. However, he also found that cultural indicators on social issues were decidedly conservative. He observed that those who labeled themselves as either liberal or conservative were among those who mainly watched TV occasionally.[11]

Resonance

Resonance occurs when things viewed on television are congruent with the actual lived realities of viewers. Gerbner writes that this provides a double dose of messages that resonate and amplify cultivation.[21] Additionally, Gerbner et al. defines resonance as the similarity between everyday reality and television narratives.[citation needed] The example they give is of minority groups whose fictional character is stereotypically more frequently victimized on television, creating an exaggerated perception of violence for individuals who watch more programming.[25]

Griffin sums this up, stating "Gerbner claimed that other heavy viewers grow more apprehensive through the process of resonance."[11] Furthermore, Gerbner said, that the "congruence of the television world and real-life circumstances may 'resonate' and lead to markedly amplified cultivation patterns."[11] This cultivation could have a large effect on our society if these viewers insist on receiving more security from the government, their workplace, family, friends, etc.

Two Measures

As either mainstreaming or resonance, cultivation produces:

First-order effects refers to learning facts.[citation needed] It is a quantitative measure where subjects are asked about their expectations of the rate of some phenomena in society, such as the possibility of becoming a violent crime victim.[26]

Second-order effects involve assumptions that people make about their environments.[10] It is also a qualitative measure investigating the perception of people's beliefs about a societal phenomenon. In this measure, various phrases are designed to describe the world (e.g., portraying society as ethical or wicked). Viewers are then asked which of these phrases reflects their beliefs.[26]

Mean World Index

Gerbner et al. developed the Mean World Index, which finds that long-term exposure to programming with frequent depictions of violence cultivates the image of a dangerous world.[citation needed] Viewers who consumed television at a higher rate believed that greater protection by law enforcement was needed and reported that most people "cannot be trusted" and are "just looking out for themselves."[22]

Heavy viewers were much more likely to see the world as a mean place. Based on frequent images of drug use on television, Minnipo and Egmont (2007) surveyed 246 Belgians over the age of 30 and found that heavy viewers were more likely to believe that most young people use drugs.[27]

The Mean World Index consists of three statements:

- Most people are just looking out for themselves,

- One can't be too careful in dealing with people, and

- Most people would take advantage of others if they got the chance.

Those with heavy viewing habits have been found to be suspicious of other people's motives, subscribing to statements that warn people to expect the worst. This mindset is what is referred to as mean world syndrome.[11] Gerbner's original analysis shows that heavy viewers are much more likely to be afraid of walking alone at night. The reluctance of these individuals has also been seen on a more global scale because heavy viewers in the United States are much more likely to believe they, as a nation, should stay out of world affairs.[28]

Heavy viewers

Heavy viewers are individuals who watch at least four hours of television a day,[11] however Nielsen defined more than 11 hours a day.[29] Heavy viewers are consistently characterized as being more susceptible to images and messages. They also rely more on television to cultivate their perceptions of the real world.[15] In a recent study done on the cultivation effects of reality television, an Indiana University study found that young girls who regularly watched the MTV hit Teen Mom had an unrealistic view of teen pregnancy.[30]

Several cognitive mechanisms that explain cultivation effects have been put forth by Shrum (1995, 1996, 1997).[31][32][33] Shrum's availability heuristic explanation suggests that heavy viewers tend to keep more frequent, recent, and vivid instances of television reality available and accessible when surveyors ask them questions, resulting in more responses related to viewing and with greater speed. Another mechanism that might explain the cultivation phenomenon is a cognitive-narrative mechanism. Previous research suggests that the realism of narratives in combination with individual-level "transportability," or the ability to adopt a less critical stance toward a narrative, might facilitate cultivation effects.[34]

Dramatic violence

Dramatic violence is the "overt expression or serious threat of physical force as part of the plot."[11]

Shows such as Law & Order SVU and CSI: Miami use murder to frame each episode of their shows, underscoring the presence of dramatic and gratuitous violence.[35] The idea of dramatic violence reinforces the relationship between fear and entertainment. Though death is being used as a plot point, it also functions to cultivate a particular image of looming violence.

Magic bullet theory

The magic bullet theory is a linear model of communication concerned with audiences directly influenced by mass media and the media's power on them.

It assumes that the media's message is a bullet fired from a media "gun" into the viewer's "head."[36] Similarly, the hypodermic needle model uses the same idea of direct injection. It suggests that the media delivers its messages straight into the passive audience's mind.[37]

Television reality

Television reality describes the effects on heavy viewers. Cultivation theory research seems to indicate that heavy viewing can result in this reality, a set of beliefs based on content rather than facts.[38] Generally, the beliefs of heavy viewers about the world are consistent with the repetitive and emphasized images and themes presented on television.[25] As such, heavy viewing cultivates a television-shaped world view.[39]

While viewers might differ in their demographic characteristics, the amount of viewing can make a difference in terms of their conceptions of social reality.[40] For instance, degrees of sex-role stereotypes can be traced to the independent contribution of TV viewing just like sex, age, class, and education.[40] Viewing time is a main element of creating television reality for the audience. According to Gerbner's research, the more time spent absorbing the world of television, the more likely people are to report perceptions of social reality which can be traced to its most persistent representations of life and society.[40]

Since the 1960s, communication scholars have examined television's contributions to viewers' perceptions of a wide variety of issues. Little effort has been made to investigate the influence of television on perceptions of social reality among adolescents.[41]

Research supports the concept of television reality as a consequence of heavy viewing. According to Wyer and Budesheim, television messages or information (even when they are not necessarily considered truthful) can still be used in constructing social judgments. Furthermore, indicted invalid information may still be used in subsequent audience's judgments.[42]

Perceptions of violence

Gerbner's initial work specifically looked at the effects of television violence on American audiences.[43] Violence underscored the larger part of Gerbner's work on cultivation theory. Therefore they measured dramatic violence, defined as "the overt expression or threat of physical force as part of the plot."[11] Gerbner's research also focused on the interpretation of the prevalence of crime on television versus reality by high-use viewers. He argues that since a high percentage of programs include violent or crime-related content, viewers who spend a lot of time watching are inevitably exposed to high levels of crime and violence.[28]

In 1968, Gerbner conducted a survey to demonstrate this theory.[citation needed] Following his previous results, he placed television viewers into three categories: light viewers (less than 2 hours a day), medium viewers (2–4 hours a day), and heavy viewers (more than 4 hours a day). He found that heavy viewers held beliefs and opinions similar to those portrayed on television, which demonstrates the compound effect of media influence.[12] They experienced shyness, loneliness, and depression much more than those who watched less often.[44] From this study, Gerbner began work on what would become the Mean World Index, which subscribes to the notion that the heavy consumption of violence-related content leads the viewer to believe the world is more dangerous than it actually is.[citation needed]

In 2012, people with heavy viewing habits were found to believe that 5% of society was involved in law enforcement. In contrast, people with light viewing habits estimated a more realistic 1%.[11]

TV viewing and fear of criminal victimization

In most of the surveys conducted by Gerbner, the results reveal a small but statistically significant relationship between television consumption and fear about becoming the victim of a crime. Those with light viewing habits predicted their weekly odds of being a victim were 1 in 100; those with heavy viewing habits predicted 1 in 10. Actual crime statistics showed the risk to be 1 in 10,000.[11]

Supporting this finding is a survey done with college students that showed a significant correlation between the attention paid to local crime and fear. There was also a significant correlation between fears of crime and violence and the number of times the respondents viewed television per week.[45]

Local television news also plays a role in influencing viewers' perception of high criminal activity. While news agencies boast their allegiance to report factually, they rely "heavily on sensational coverage of crime and other mayhem with particular emphasis on homicide and violence."[46] Gerbner found that heavy viewers were more likely to overestimate crime rates and risk of personal exposure to crime and underestimate the safety of their neighborhoods.[47]

Busselle (2003) found that parents who watch more programs portraying crime and violence are more likely to warn their children about crime during their high school years; these warnings in turn predicted the students' own crime estimates.[48]

Research applications

Although Gerbner's research focused on violence on TV this theory can be applied to a variety of different situations. Many other theorists have done studies related to the cultivation theory which incorporated different messages than Gerbner's original intent. This research has been conducted in order to defeat two criticisms of the theory; its breadth and lumping of genres.

Cultivation effects on children

There was a positive relationship between childhood television viewing levels and the social reality beliefs in young adulthood.[citation needed] The results of one study suggest that television viewed during childhood may affect the social reality beliefs a person holds as an adult.[11] Accordingly, Griffin's (2012) study focused on the potential effect of childhood television viewing on social reality beliefs during adulthood and childhood exposure to television genres that tend to be violent.[6]

Another longitudinal study shows how television exposure is associated with overall self-esteem in children. Nicole Martins and Kristen Harrison (2011) measured the amount of television viewing in elementary school children and their overall level of self-esteem (not related to perceptions about the body) after television exposure over time. They found that higher levels of television viewing predicted lower self-esteem for White girls, Black girls, and Black boys, but higher self-esteem for White boys. This relationship indicates that exposure to portrayals of White males on television, which tend to be positive, and those of Black men and women and White women which tend to be negative, shape the way children understand their own identities.[49]

International cultivation analysis

International cultivation analysis attempts to answer the question of whether the medium or the system is the message. Gerbner et al. (1994) found that countries where the television programs were less repetitive and homogeneous than the United States produced less predictable and consistent results.[25]

The variety of television content is also an important factor. Increased diversity and balance within television channels or programs leads viewers to report similar preferences.[citation needed] Furthermore, importing television programs internationally can elicit variable responses depending on the cultural context and the type of television program.[citation needed] For example, exposure of US television programs to Korean females portrayed a liberal perspective of gender roles and family.[citation needed] However, for the Korean male television viewers, US programs brought out increased hostility and protection of Korean culture.[citation needed]

Another study showed that Australian students who watched US television programs (especially adventure and crime shows) were more likely to view Australia as dangerous;[25] however, they didn't transfer this danger to America, even though they were watching US television programs. A study conducted by Minnebo and Eggermont (2007) found that heavy television viewers, over the age of 30, in Belgium "were more likely to believe that most young people are substance users."[9][citation needed]

Lifetime television exposure analysis

In order to accurately survey and represent findings from cultivation theory research, the duration of television exposure has become a topic for further research. It is stated that the "cultivation effect only occurs after long-term, cumulative exposure to stable patterns of content on television."[15] However, research that tracks long-term media exposure is very rare and if conducted, must be thoroughly planned out in order to secure dependable results. In a study conducted in 2009, participants were asked to list the number of Grey's Anatomy episodes they had viewed in prior and current seasons.[citation needed] The purpose of the study was to gain a perspective of how viewers see doctors based on impressions from television. Findings from the study showed a positive association with Grey's Anatomy's portrayal with real-world doctors' acts of courage. The finding was not surprising, as many episodes within Grey's Anatomy often show doctors as courageous, either by employing a detailed view of an operation or crediting doctors for their empathy in specific patient scenarios.[citation needed] Gerbner and colleagues argue that cultivation effects span total television viewing, not a genre- or program-specific viewing.[50] In a study conducted by Jonathan Cohen and Gabriel Weimann, they found that cultivation through television is more prevalent within the age group of older teenagers and young adults, thus supporting the claim that a cumulative exposure to television throughout a viewer's life has a steady impact on their cultivation longevity.[51]

Impact on psychosocial health

A study conducted by Hammermeister, Brock, Winterstein, and Page (2005) compares the psychosocial health of viewers that reported no television use, viewers who followed the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) suggested consumption of up to 2 hours of television per day and viewers with high exposure to television. They surveyed 430 participants within the United States implemented via survey method. They found that there was more of an impact on the psychosocial health of women who participated in the study and, "revealed that all the psychosocial variables examined in this study contributed significantly to the one function equation with depression, hopelessness, self-esteem, and weight satisfaction being the strongest discriminators."[44]:260 Findings also exposed the similarity in psychosocial health data between participants who watched up to 2 hours of television per day and participants who opt out of television consumption altogether.[44]

InterTV

InterTV is a concept forecasting the melding of television and online media. As described by Shanahan and Morgan (1999) as television's "convergence" with computers, they argue that computers will essentially act as an extension of television through the creation of related websites and online news articles covered within the traditional television journalism realm. Additionally, television programming will also suffer a shift to an online platform as a result of streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu. According to Shanahan and Morgan, this may not be the worst thing, as it allows advertisers a direct source in which they can gather information regarding viewers. They state that "within a market filled with individual interests, desires, and the channels to serve them, such a data-gathering enterprise would still allow advertisers to assemble mass audiences from the fragmented media systems." In a sense, this would allow viewers some way to control the content they are fed through the online platform. While advertisers are infringing on viewer information, the correlated result requires them to shift any programming or storyline content to the satisfaction of the viewer. This poses a challenging example in terms of extending the impact of cultivation theory, instead of empowering the viewer to cultivate their own television use experience.[15]

Music

Kathleen Beullens, Keith Roe, and Jan Van den Bulck (2012) conducted research relating to alcohol consumption in music videos. The research revealed that high exposure to music videos develops an unrealistic perception of alcohol consumption. Musicians in these videos endorse alcohol in their songs and create a false reality about alcohol and its effects."[52]

Examining violent trends in hip-hop journalism, a study by Tyree Oredein, Kiameesha Evans, and M. Jane Lewis (2020) suggests that a significant portion of hip-hop journalism contains violence, which is being communicated to impressionable audiences. The research reveals that in line with cultivation theory's construct of resonance, adolescents who are more likely to identify with hip-hop celebrities may be more likely to engage in violent behavior when an attractive celebrity suggests violent behavior.[53]

Video games

Research conducted by Dmitri Williams (2006) draws the comparison of the effects of television to interactive video games. He argues that while the parameters and basic content of the game developed is through the employment of game developers, creators, and designers, the role of the "other player" within the game is also essential in the progression of the story within the video game. Essentially, an interactive game allows players to build relationships with others and thus is more dynamic and unpredictable as compared to traditional television. Williams attempts to research the question of whether video games are as influential as television from a cultivation theory standpoint. Does it impact our social reality? In the field study, participants were asked to play a MMORPG game, one in which participants interacted with other players in real-time. Crime measures divided into four categories were used to evaluate the correlation between the research hypotheses and cultivation theory. The study proved a strong correlation between the impact of cultivation on participants and the players of the MMORPG game.[54]

Another study was carried out testing another game, more specifically Grand Theft Auto IV (GTA IV). In this study, the basics of the cultivation theory were tested. Test subjects were to play a violent video game, in this case, GTA IV over a three-week setting for 12 hours in a controlled environment. This allowed for more accurate data later on. Afterward, each participant had to fill out a questionnaire. These results were compared to a controlled set of data (people who did not play video games), to see if the video games or violence actually had an effect on people. The study however concluded no real correlation, indicating there could be no possible link between playing violent games and becoming more violent.[55][56]

LGBT

Sara Baker Netzley (2010) conducted research in a similar fashion to Gerbner in the way that gay people were depicted on television. This study found that there was an extremely high level of sexual activity in comparison to the number of gay characters that appeared on television. This has led those who are heavy television consumers to believe that the gay community is extremely sexual.[57] Much like the idea of a mean and scary world it gives people a parallel idea of an extremely sexualized gay community.[57]

In a study conducted by Jerel Calzo and Monique Ward (2009), they first begin by analyzing recent research conducted on the portrayal of gay and lesbian characters on television. While growth in the representation of gay and lesbian characters has continued to grow, they found that most television shows frame gay and lesbian characters in a manner that reinforces LGBT stereotypes. Diving into the discussion, they even use examples such as Ellen and Will & Grace, describing the storyline content as reinforcing "stereotypes by portraying these characters as lacking stable relationships, as being preoccupied with their sexuality (or not sexual at all), and by perpetuating the perception of gay and lesbian people as laughable, one-dimensional figures. Their findings confirmed that media genres played an important role in the attitudes developed regarding homosexuality. They also were surprised by the finding that prior prime-time shows, which are no longer on air, reinforced a larger magnitude of acceptance within the LGBTQ realm. They then suggested that because genre played a large impact in the perception that viewers gained while watching certain television shows, more research should be designated towards, "more genre-driven effects analyses."[58]

Women

Beverly Roskos-Ewoldsen, John Davies, and David Roskos-Ewoldsen (2004) posit that perceptions of women are integrated in a rather stereotypical fashion compared to portrayals of men on television. They state that, "men are characters in TV shows at about a 2 to 1 ratio to women." Viewers who consume more television usually also have more traditional views of women.[59] Research has also shown that women are more likely to be portrayed as victims on television than men.[60]

Alexander Sink and Dana Mastro (2017) studied women and gender depictions on American prime time television. Although women are often perceived to have better representation on television in recent years, these researchers claim that this is not necessarily the case. They claim women are proportionally underrepresented on prime time television, making up 39% of characters despite the fact that women make up 50.9% of the population in the US. Men were also portrayed as more dominant than women, and although men were more often objectified, women were consistently portrayed as hyper-feminized and hyper-sexualized. Fewer older women appeared during primetime compared to men and were often shown to be less competent than older male characters.[61]

Sexual attitudes

A study by Bradley J. Bond and Kristin L. Drogos (2014) examined the relationship between exposure to the television program Jersey Shore and sexual attitudes and behavior in college-aged adults. They found a positive relationship between time spent watching Jersey Shore and increased sexual permissiveness. This effect was found to be stronger in the younger participants than older participants and held true even when the researchers controlled for other influences on participants' sexual attitudes such as religious beliefs and parents' attitudes. This higher level of sexually permissive behavior and attitudes was not a result of higher overall exposure to television, but to higher exposure to Jersey Shore, a highly sexualized program, specifically.[62]

Race and ethnicity

Meghan S. Sanders and Srividya Ramasubramanian (2012) studied perceptions which African American media consumers hold about fictional characters portrayed in film and television. They found that, while study participants tended to view all African American characters positively, social class, rather than race or ethnicity, mattered more in perceptions about the warmth and competence of a character. Their study suggests that the race and ethnicity of media consumers need to be taken into account in cultivation studies because media consumers with different backgrounds likely perceive media portrayals and their faithfulness to reality differently.[63]

A study by Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz and David Ta (2014) examined the cultivation effects of video games on White students' perceptions of Black and Asian individuals. While no significant effects were found for perceptions of Asian individuals, researchers found that increased time spent playing video games, no matter what genre, held less positive views of Black people. They also found that real-life interaction with Black individuals did not change this effect. Behm-Morawitz and Ta suggest that the stable, negative racial and ethnic stereotypes portrayed in video game narratives of any genre impact real-world beliefs in spite of more varied real-life interactions with racial and ethnic minorities.[56]

Politics and policy preferences

Diana C. Mutz and Lilach Nir (2010) conducted a study of how fictional television narratives can influence viewers' policy preferences and positive or negative attitudes regarding the justice system in the real world. They found that positive portrayals of the criminal justice system were associated with more positive views toward the system in real life, whereas negative television portrayals were associated with viewers feeling that the criminal justice system often works unfairly. Furthermore, researchers found that these attitudes did influence viewers' policy preferences concerning the criminal justice system in real life.[64]

A study by Anita Atwell Seate and Dana Mastro (2016) studied news coverage of immigration and its relationship with immigration policy preferences and negative attitudes about immigrants. They found that exposure to negative messages about immigrants in the news influenced anxious feelings towards the outgroup (i.e. immigrants), particularly when the news showed an example of a member of this outgroup on the program. This exposure did not necessarily influence immigration policy preferences, but long-term exposure to messages of this kind can affect policy preferences.[65]

Katerina-Eva Matsa (2010) explored cultivation effects through her thesis on television's impact on political engagement in Greece. She did so by describing the role of satirical television within the cultural realm in Greece and how this form of television engrained the perception that Greek political institutions are corrupt, thus negatively influencing the public's overall opinion of politics in Greece.[66]

New media

Michael Morgan, James Shanahan, and Nancy Signorielli (2015) conceptualize applications of cultivation theory to the study of new media. They note that media technology has not been static, and that media may continue to evolve. However, in the present, older methods for cultivation analysis may have to move away from counting hours of television viewed, and take up a big data approach. These authors argue that, although many were skeptical that cultivation theory would be applicable with the increasing importance of new media, these media still use narrative, and since those narratives affect us, cultivation theory is still relevant for new media.[67]

Stephen M. Croucher (2011) applies cultivation theory to his theory of social media and its effects on immigrant cultural adaptation. He theorizes that immigrants who use dominant social media while they are still in the process of adapting to their new culture will develop perceptions about their host society through the use of this media. He believes that this cultivation effect will also impact the way immigrants interact with host country natives in offline interactions.[68]

In a 2020 article titled "Facebook and the cultivation of ethnic diversity perceptions and attitudes", there is research that applies cultivation theory to social network sites by investigating how Facebook uses cultivates users’ ethnic diversity perceptions and attitudes. Findings of this study shows that cultivation effects are prevalent on Facebook, but the cultivation variables differ in respect to the distance to the media audience's social environments and in relation to the nature of effects. This study revealed positive cultivation effects. That is, Facebook conveys to users a reality that is ethnically diverse, which, in turn, positively influences ethnic diversity perceptions and attitudes.[69]

Mina Tsay-Vogel, James Shanahan, and Nancy Signorielli (2016) conducted a study concerning social media cultivating perceptions of privacy, examining the impact of SNSs on privacy attitudes and self-expression behaviors using a cultivation perspective. It investigates the impact of Facebook use on privacy perceptions and self-expression behaviors over a five-year period from 2010 to 2015. Findings at the global level support the social role of Facebook in fostering more relaxed attitudes toward privacy and subsequently increasing self-expression in both offline and online environments.[70]

Sports

Cultivation theory attempts to predict that media viewing has an effect on the values and beliefs that people have and the things they believe are "reality". A study conducted by David Atkin from the University of Connecticut revealed insights about television viewing of sports and the values of its viewers. The hypothesis stated that the "Level of agreement with sports-related values (i.e., being physically fit, athletic, and active) is positively related to participation in sports-related media and leisure activities."[71][citation needed] The results from the study supported the hypothesis, specifically that "those for whom being physically fit, being athletic and being active are important also engage in more sports media."[citation needed] In this instance, cultivation theory is present because heavier exposure is related to greater agreement with the values that are presented.

In an article entitled "Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media and Politics", concluded that "the line of research has found that, as exposure to television increases, an individual's beliefs and opinions of the real-world become more similar to that of the television world." This statement proves to be in support of the previous hypothesis and supports cultivation theory being present in the sporting world, in the sense that the more sport-related media that someone consumes, the more likely they are to value being physically fit.

Another aspect of cultivation theory being studied in relation to sports is the difference between those who participate in sporting events and those who watch them. Another part of cultivation theory can be explained by people being less active, because of what they watch on television and the rise in obesity levels. Because people don't see a lot of active people on television, their "reality" is that people no longer need to be active 30 or so minutes per day.

Cultivation theory can be applied to sports as it can be applied to many other areas of media. A prime example of this is America's shift toward so-called "violent sports".[citation needed] A survey undertaken in 1998 shows that only 67% of American teenagers considered themselves to be baseball fans, compared to 78% who responded identifying themselves as football fans.[citation needed] This study correlates with current TV ratings, as football has by far the most hours watched since 2005 at 111.9 million hours.[citation needed] Leo W. Jeffres, Jae-Won Lee, and Kimberly A. Neuendorf say that "new "media logic" that favors more violent, action-oriented sports" has emerged, "while slower-paced sports have been relegated to secondary status in the United States."

Although there was no true correlation between the cultivation theory and sports, there has been research conducted on the level of violence in sports content and the effects it has on viewers. Results found by Raney and Depalma (2006) found that individuals were less likely to report being in a positive mood after watching violent sports content and its effect on viewers.

Altruistic behaviors

Zakir Shah, Jianxun Chu, Usman Ghani, Sara Qaisar. and Zameer Hassan (2020) conducted research that focused on the mediating role of fear of victimization in the cultivation theory perspective. This is the first study to determines the mediating effect of fear of victimization between exposure to media and perception of media with the altruistic behaviors of individuals. Based on cultivation theory, authors suggest that exposure to media and the perception of people about the media on which they exposed to disaster-related information affect their fear of victimization and altruistic behaviors. Findings show that high exposure to disaster-related news and individuals’ perception of the media contributed to more fear of victimization. Moreover, fear of victimization from disaster significantly influences the altruistic behaviors of people.[72]

Criticisms

A number of scholars have critiqued Gerbner's assertions about cultivation theory, particularly its intentions and scope. One critique of the theory analyzes the objective of the theory. Communications professor Jennings Bryant posits that cultivation research focuses more on the effects rather than who or what is being influenced. Bryant goes on to assert that the research to date has more to do with the "whys" and "hows" of a theory as opposed to gathering normative data as to the "whats", "whos", and "wheres".[73]

Theoretical leap

Critics have also faulted the logical consistency of cultivation analysis, noting that the methods employed by cultivation analysis researchers do not match the conceptual reach of the theory.[citation needed] The research supporting this theory uses social scientific methods to address questions related to the humanities.[7] Another possibility is that the relationship between TV viewing and fear of crime is like the relationship between a runny nose and a sore throat. Neither one causes the other—they are both caused by something else."[11] Many also question the breadth of Gerbner's research. When using the Cultural Indicators strategy, Gerbner separated his research into three parts.[citation needed] The second part focused on the effects of media when looking at gender, race/ethnicity, and occupation.[citation needed] Michael Hughes writes: "it does not seem reasonable that these three variables exhaust the possibilities of variables available…which may be responsible for spurious relationships between television watching and the dependent variables in the Gerbner et al. analysis."[28]:287 Also, the variables Gerbner did choose can also vary by the amount of time a person has available to watch TV.[citation needed]

Lived experience

Another critique comes from Daniel Chandler:

[T]hose who live in high-crime areas are more likely to stay at home and watch television and also to believe that they have a greater chance of being attacked than are those in low-crime areas." He claims as well, "when the viewer has some direct lived experience of the subject matter this may tend to reduce any cultivation effect.[74]

While television does have some effect on how we perceive the world around us, Gerbner's study does not consider the lived experiences of those that do inhabit high crime areas.

Forms of violence

Gerbner is also criticized for his lumping of all forms of violence. Chandler argues, "different genres—even different programs—contribute to the shaping of different realities, but cultivation analysis assumes too much homogeneity in television programs".[74] This point is addressed by Horace Newcomb (1978) who argues that violence is not presented as uniformly on television as the theory assumes; therefore, television cannot be responsible for cultivating the same sense of reality for all viewers.[75] When considering different programs that are on television, it makes sense that scholars would criticize Gerbner's lack of categories. For example, Saturday morning cartoon "play" violence is in combination with a murder on Law and Order. This does not seem to logically fuse together. Morgan and Shanahan understand this dispute, but they contend "that people (especially heavy viewers) do not watch isolated genres only, and that any 'impact' of individual program types should be considered in the context of the overall viewing experience."[9]

A study by Karyn Riddle attempts to address this critique, however, by combining heuristic processing models with cultivation theory to examine how not just exposure to violence in television, but also how vividly it is portrayed impacts cultivation effects. She found that there was an interaction effect for portrayals that were vivid and viewed frequently. In this case, real-world beliefs were significantly affected.[76]

Humanist critique

Cultivation analysis has also been criticized by humanists for examining such a large cultural question. Because the theory discusses cultural effects, many humanists feel offended, thinking that their field has been misinterpreted. Horace Newcomb writes, "More than any other research effort in the area of television studies the work of Gerbner and Gross and their associates sits squarely at the juncture of the social sciences and the humanities."[75]:265

The theory has also received criticism for ignoring the issue of perceived realism of the televised content, which could be essential in explaining people's understanding of reality.[77] Barbra Wilson, Nicole Martins, and Amy Markse argue that attention to television might be more important to cultivating perceptions than only the amount of television viewing.[78] In addition, C. R. Berger writes that the cultivation analysis theory is less useful than desired because it ignores cognitive processes, such as attention or rational thinking style.[79]

Perceived reality

The supposed correlation between cultivation effects and perceived reality has been criticized due to the inconsistent findings from various research conducted on the subject. Hawkins and Pingree (1980) found that participants that reported a lower perceived reality scoring actually showed a stronger cultivation impact. Potter (1986) found that "different dimensions and levels of perceived reality were associated with different magnitudes of cultivation effects". Additionally, a study conducted by Shrum, Wyer, and O'Guinn (1994) showed a zero percentage correlation between perceived reality and cultivation effects.

Utility

Cultivation analysis has been criticized that its claims are not always useful in explaining the phenomenon of interest: how people see the world.[citation needed] Some also argue that violence is not presented as uniformly on television as the theory assumes, so television cannot be reliably responsible for cultivating the same sense of reality for all viewers. In addition, cultivation analysis is criticized for ignoring other issues such as the perceived realism of the televised content, which might be critical in explaining people's understanding of reality. Attention to television might be more important to cultivating perceptions than simply the amount of television viewing, so the fact that the cultivation analysis theory seems to ignore cognition such as attention or rational thinking style deems it to be less useful.[7]

See also

References

- Bilandzic, Helena; Rössler, Patrick (2004-01-12). "Life according to television. Implications of genre-specific cultivation effects: The Gratification/Cultivation model". Communications. 29 (3). doi:10.1515/comm.2004.020. ISSN 0341-2059.

- Nabi, Robin L.; Riddle, Karyn (2008-08-08). "Personality Traits, Television Viewing, and the Cultivation Effect". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 52 (3): 327–348. doi:10.1080/08838150802205181. ISSN 0883-8151. S2CID 144333259.

- Communication, in Cultural; Psychology; Behavioral; Science, Social (2010-01-14). "Cultivation Theory". Communication Theory. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- "Cultivation Theory by George Gerbner & Larry Gross". toolshero. 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- Settle, Quisto (2018-11-05). "Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application". Journal of Applied Communications. 102 (3). doi:10.4148/1051-0834.1223. ISSN 1051-0834.

- Riddle, K. (2009). Cultivation Theory Revisited: The Impact of Childhood Television Viewing Levels on Social Reality Beliefs and Construct Accessibility in Adulthood (Conference Papers). International Communication Association. pp. 1–29.

- West, R. & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application (Fourth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Bryant, J.; Mirion, D. (2004). "Theory and research in mass communication". Journal of Communication. 54 (4): 662–704. doi:10.1093/joc/54.4.662.

- Morgan, M.; Shanahan, J. (2010). "The State of Cultivation". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 54 (2): 337–355. doi:10.1080/08838151003735018. S2CID 145520112.

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M. & Signorielli, N. (1986). "Living with television: The dynamics of the cultivation process". In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (eds.). Perspectives on media effects. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 17–40.

- Griffin, E. (2012). Communication Communication Communication. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. (8), 366–377.

- Potter, W. James (1 December 2014). "A Critical Analysis of Cultivation Theory". Journal of Communication. 64 (6): 1015–1036. doi:10.1111/jcom.12128. ISSN 1460-2466. S2CID 143285507.

- Arendt, F. (2010). Cultivation effects of a newspaper on reality estimates and explicit and implicit attitudes. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, And Applications, 22(4), 147-159

- "Methods of Cultivation: Assumptions and Rationale", Television and its Viewers, Cambridge University Press, pp. 20–41, 1999-09-09, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511488924.003, ISBN 978-0-521-58755-6, retrieved 2020-11-16

- Shanahan, J; Morgan, M (1999). Television and its viewers: Cultivation theory and research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 286–302. ISBN 978-1-4331-1368-0.

- "The Man Who Counts the Killings". The Atlantic. May 1997. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- West, Richard; Turner, Lynn (2014). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 420–436. ISBN 978-0-07-353428-2.

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Jackson-Beeck, M.; Jeffries-Fox, S.; Signorielli, N. (1978). "Cultural indicators violence profile no. 9". Journal of Communication. 28 (3): 176–207. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01646.x. PMID 690257. S2CID 34741270.

- Gerbner, G. & Gross, L. (1972). "Living with television: The violence profile". Journal of Communication. 26 (2): 173–199. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1976.tb01397.x. PMID 932235.

- Baran, S. J., & Davis, D. K. (2015). Mass communication theory: Foundations, ferment, and future. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Pub. Co.

- Gerbner, G. (1998). "Cultivation Analysis: An Overview". Mass Communication and Society. 1 (3–4): 175–194. doi:10.1080/15205436.1998.9677855.

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M.; Signorielli, N. (1980). "The "Mainstreaming" of America: Violence Profile No. 11". Journal of Communication. 30 (3): 10–29. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x.

- Gerbner, George; Gross, Larry; Morgan, Michael; Signorielli, Nancy (1980-09-01). "The "Mainstreaming" of America: Violence Profile No. 11". Journal of Communication. 30 (3): 10–29. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x. ISSN 0021-9916.

- Perse, E. M. (2005-03-01). "Against the Mainstream: The Selected Works of George Gerbner: Edited by Michael Morgan. New York: Peter Lang, 2002. 528 pp. $73.95 (hard), $29.95 (soft)". Journal of Communication. 55 (1): 187–188. doi:10.1093/joc/55.1.187. ISSN 0021-9916.

- Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Signorielli N (1994). "Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective". In M. Morgan (ed.). Against the mainstream: The selected works of George Gerbner. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 193–213.

- Mosharafa, Eman (2015-09-11). "All you Need to Know About: The Cultivation Theory". Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research. ISSN 2249-460X.

- Minnebo, Jurgen; Eggermont, Steven (2007). "Watching the young use illicit drugs". Young. 15 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1177/110330880701500202. S2CID 143581378.

- Hughes, Michael (1980). "The Fruits of Cultivation Analysis: A Reexamination of Some Effects of Television Watching". Public Opinion Quarterly. 44 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1086/268597.

- "Tipping the Scale: Heavy TV Viewers=a Big Opportunity for Advertisers". www.nielsen.com. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Study: Heavy viewers of 'Teen Mom' and '16 and Pregnant' have unrealistic views of teen pregnancy: IUB Newsroom: Indiana University". news.indiana.edu. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Shrum, L.J. (1995). "Assessing the social influence of television: A social cognitive perspective on cultivation effects". Communication Research. 22 (4): 402–429. doi:10.1177/009365095022004002. S2CID 145114684.

- Shrum, L.J. (1996). "Psychological processes underlying cultivation effects: Further tests of construct accessibility". Human Communication Research. 22 (4): 482–509. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00376.x.

- Shrum, L.J. (1997). "The role of source confusion in cultivation effects may depend on processing strategy: A comment on Mares (1996)". Human Communication Research. 24 (2): 349–358. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00418.x.

- Bilandzic, H.; Busselle, R.W (2008). "Transportation and transportability in the cultivation of genre-consistent attitudes and estimates". Journal of Communication. 58 (3): 508–529. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00397.x.

- Berger, A. A. (Ed.). (1987). Television in society. Transaction Publishers.

- Arthur Asa, Berger (5 July 1995). Essentials of Mass Communication Theory (1 ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

- Croteau, D.; Hoynes, W (1997). Industries and Audience. London: Pine Forge Press.

- Tony R., DeMars (2000). Modeling Behavior from Images of Reality in Television Narratives. US: The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd. p. 36.

- Hawkins, R. P.; Pingree, S.; Alter, I (1987). Searching for cognitive processes in the cultivation effect: Adult and adolescent samples in the United States and Australia. pp. 553–577.

- Gerbner, George; Larry Gross; Nancy Signorielli; Michael Morgan (1980). "Aging with Television: Image on Television Drama and Conceptions of Social Reality". Journal of Communication. 30 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01766.x. PMID 7372841.

- Jong G. Kang; Stephen S. Andersen; Michael Pfau (1996). "Television Viewing and Perception of Social Reality Among Native American Adolescents" (PDF). Illinois State University, Augustana College University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Wyer, Robert S.; William H. Unverzagt (1985). "Effects of Instructions to Disregard Information on Its Subsequent Recall and Use in Making Judgments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 48 (3): 533–549. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.3.533. PMID 3989660.

- "Media Effects Theories". Oregon State University.

- Hammermeister, Joe; Barbara Brock; David Winterstein; Randy Page (2005). "Life Without TV? Cultivation Theory and Psychosocial Characteristics of Television-Free Individuals and Their Television-Viewing Counterparts" (PDF). Health Communication. 17 (4): 253–264. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1703_3. PMID 15855072. S2CID 18565666.

- Reber, Bryan H.; Yuhmim Chang (1 September 2000). "Assessing cultivation theory and public health model for crime reporting". Newspaper Research Journal. 21 (4): 99–112. doi:10.1177/073953290002100407. S2CID 152903384.

- Hamilton, 1998; Klite, Bardwell, & Salzman, 1995, 1997

- 60.Lett, M. D., DiPietro, A. L., & Johnson, D. I. (2004). Examining Effects of Television News Violence on College Students through Cultivation Theory. Communication Research Reports, 21(1), 39–46.

- Busselle, Rick W. (October 2003). "Television Exposure, Parents' Precautionary Warnings, and Young Adults' Perceptions of Crime". Communication Research. 30 (5): 530–556. doi:10.1177/0093650203256360. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 35569859.

- Martins, Nicole; Harrison, Kristen (16 March 2011). "Racial and Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Children's Television Use and Self-Esteem". Communication Research. 39 (3): 338–357. doi:10.1177/0093650211401376. S2CID 26199959.

- Quick. "The Effects of Viewing Grey's Anatomy on Perceptions of Doctors and Patient Satisfaction". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- Cohen, J. & Weimann, G. (2000). "Cultivation revisited: Some genres have some effects on some viewers". Communication Reports. 13 (2): 99–114. doi:10.1080/08934210009367728. S2CID 144833310.

- Beullens, K.; Roe, K.; Van; den Bulck, J. (2012). "Music Video Viewing as a Marker of Driving After the Consumption of Alcohol". Substance Use & Misuse. 47 (2): 155–165. doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.637449. PMID 22217069. S2CID 32434210.

- Oredein, Tyree; Evans, Kiameesha; Lewis, M. Jane (2020-01-19). "Violent Trends in Hip-Hop Entertainment Journalism". Journal of Black Studies. 51 (3): 228–250. doi:10.1177/0021934719897365. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 213058566.

- Williams, Dmitri (2006). "Virtual cultivation: Online worlds, offline perceptions". Journal of Communication. 56: 69–87. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00004.x. S2CID 4661334.

- "Cultivation Effects of Video Games: A Longer-Term Experimental Test of First- and Second-Order Effects". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- Behm-Morawitz, Elizabeth; Ta, David (1 January 2014). "Cultivating Virtual Stereotypes?: The Impact of Video Game Play on Racial/Ethnic Stereotypes". Howard Journal of Communications. 25 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/10646175.2013.835600. ISSN 1064-6175. S2CID 144462796.

- Netzley, S (2010). "Visibility That Demystifies Gays, Gender, and Sex on Television". Journal of Homosexuality. 57 (8): 968–986. doi:10.1080/00918369.2010.503505. PMID 20818525. S2CID 5230589.

- Jerel P. Calzo M.A. & L. Monique Ward (2009). "Media Exposure and Viewers' Attitudes Toward Homosexuality: Evidence for Mainstreaming or Resonance?". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 53 (2): 280–299. doi:10.1080/08838150902908049. S2CID 144908119.

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, Beverly; Davies, John; Roskos-Ewoldsen, David (2004). "Implications of the mental models approach for cultivation theory". Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research. 29 (3). doi:10.1515/comm.2004.022.

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K. H.; Aday, S. (2003). "Television news and the cultivation of fear of crime". Journal of Communication. 53 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb03007.x. S2CID 16535313.

- Sink, Alexander; Mastro, Dana (2 January 2017). "Depictions of Gender on Primetime Television: A Quantitative Content Analysis". Mass Communication and Society. 20 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/15205436.2016.1212243. ISSN 1520-5436. S2CID 151374826.

- Bond, Bradley J.; Drogos, Kristin L. (2 January 2014). "Sex on the Shore: Wishful Identification and Parasocial Relationships as Mediators in the Relationship Between Jersey Shore Exposure and Emerging Adults' Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors". Media Psychology. 17 (1): 102–126. doi:10.1080/15213269.2013.872039. ISSN 1521-3269. S2CID 145263485.

- Sanders, Meghan S.; Ramasubramanian, Srividya (1 January 2012). "An Examination of African Americans' Stereotyped Perceptions of Fictional Media Characters". Howard Journal of Communications. 23 (1): 17–39. doi:10.1080/10646175.2012.641869. ISSN 1064-6175. S2CID 144745770.

- Mutz, Diana C.; Nir, Lilach (31 March 2010). "Not Necessarily the News: Does Fictional Television Influence Real-World Policy Preferences?". Mass Communication and Society. 13 (2): 196–217. doi:10.1080/15205430902813856. ISSN 1520-5436. S2CID 143452861.

- Seate, Anita Atwell; Mastro, Dana (2 April 2016). "Media's influence on immigration attitudes: An intergroup threat theory approach". Communication Monographs. 83 (2): 194–213. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1068433. ISSN 0363-7751. S2CID 146477267.

- Matsa, K. E. (2010). Laughing at politics: effects of television satire on political engagement in Greece (PDF) (Thesis). Georgetown University.

- Morgan, Michael; Shanahan, James; Signorielli, Nancy (3 September 2015). "Yesterday's New Cultivation, Tomorrow". Mass Communication and Society. 18 (5): 674–699. doi:10.1080/15205436.2015.1072725. ISSN 1520-5436. S2CID 143254238.

- Croucher, Stephen M. (1 November 2011). "Social Networking and Cultural Adaptation: A Theoretical Model". Journal of International and Intercultural Communication. 4 (4): 259–264. doi:10.1080/17513057.2011.598046. ISSN 1751-3057. S2CID 143560577.

- Hermann, Erik; Eisend, Martin; Bayón, Tomás (2020-04-20). "Facebook and the cultivation of ethnic diversity perceptions and attitudes". Internet Research. 30 (4): 1123–1141. doi:10.1108/intr-10-2019-0423. ISSN 1066-2243.

- Tsay-Vogel, Mina; Shanahan, James; Signorielli, Nancy (2016-08-02). "Social media cultivating perceptions of privacy: A 5-year analysis of privacy attitudes and self-disclosure behaviors among Facebook users". New Media & Society. 20 (1): 141–161. doi:10.1177/1461444816660731. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 4927843.

- David Atkin, p. 324

- Shah, Zakir; Chu, Jianxun; Ghani, Usman; Qaisar, Sara; Hassan, Zameer (January 2020). "Media and altruistic behaviors: The mediating role of fear of victimization in cultivation theory perspective". International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 42: 101336. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101336. ISSN 2212-4209.

- Bryant, Jennings. (1 March 1986). "The Road Most Traveled: Yet Another Cultivation Critique". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 30 (2): 231–335. doi:10.1080/08838158609386621.

- Chandler, Daniel. Cultivation Theory Archived 2011-12-06 at the Wayback Machine. Aberystwyth University, 18 September 1995.

- Newcomb, H (1978). "Assessing the violence profile studies of Gerbner and Gross: A humanistic critique and suggestion". Communication Research. 5 (3): 264–283. doi:10.1177/009365027800500303. S2CID 144063275.

- Riddle, Karyn (28 May 2010). "Always on My Mind: Exploring How Frequent, Recent, and Vivid Television Portrayals Are Used in the Formation of Social Reality Judgments". Media Psychology. 13 (2): 155–179. doi:10.1080/15213261003800140. ISSN 1521-3269. S2CID 145074578.

- Minnebo, J.; Van Acker, A. (2004). "Does television influence adolescents' perceptions of and attitudes toward people with mental illness?". Journal of Community Psychology. 32 (3): 267–275. doi:10.1002/jcop.20001.

- Wilson, B. J.; Martins, N.; Marske, A. L. (2005). "Children's and parents' fright reactions to kidnapping stories in the news". Communication Monographs. 72: 46–70. doi:10.1080/0363775052000342526. S2CID 145234887.

- Berger, C. R. (2005). "Slippery slopes to apprehension: Rationality and graphical depictions of increasingly threatening trends". Communication Research. 32: 3–28. doi:10.1177/0093650204271397. S2CID 30419868.

Further reading

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M.; Signorielli, N.; Jackson-Beeck, M. (1979). "The Demonstration of Power: Violence Profile No. 10". Journal of Communication. 29 (3): 177–196. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1979.tb01731.x. PMID 479387.