Cuterebra fontinella

Cuterebra fontinella, the mouse bot fly, is a species of New World skin bot fly in the family Oestridae. C. fontinella is typically around 1 mm long with a black and yellow color pattern.[2] C. fontinella develops by parasitizing nutrients from its host, typically the white-footed mouse.[1][3][4][5][6][7] C. fontinella has even been known to parasitize humans in rare cases.[8] Individuals parasitized by C. fontinella will develop a large bump on the skin that is indicative of parasitization.[9]

| Cuterebra fontinella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cuterebra fontinella, also known as the Mouse Bot Fly | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Oestridae |

| Genus: | Cuterebra |

| Species: | C. fontinella |

| Binomial name | |

| Cuterebra fontinella Clark, 1827 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Etymology

The genus name Cuterebra is a blend of the Latin words cutis : skin and terebra : borer.

Distribution

C. fontinella is found all around North America. C. fontinella has been found in most of the continental United States, Southern Canada, and Northern Mexico.[10][11] The prevalence of C. fontinella is reliant on temperature, so colder regions will not be as densely populated as the warmer ones.

Habitat

C. fontinella inhabits deciduous forests of North America.[11] C. fontinella prefer territories near running water and with low-elevation vegetation. These flies are found in the highest density near the edges of their habitats.[10]

Description

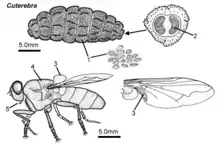

C. fontinella look very similar to other species within the Cuterebra genus but have a few distinguishing features. The easiest indicator to use is the host species, as different species of Cuterebra infest different hosts. However, this method is not always reliable as C. fontinella have been known to infest multiple host species in addition to their preferred host, Peromyscus leucopus, the white-footed mouse. C. fontinella eggs are typically 1.05 mm long and 0.03 mm wide. They are shaped like canoes and have a large groove along their underside; this groove enables attachment to vegetation.[12] C. fontinella larvae transition from golden brown to black during development. The larvae are oval in shape. Grown larvae are typically 22 mm long, 13.9 mm wide, and 12.5 mm thick. The larva is segmented into 12 sections, with backwards facing conical spines on almost every segment. The head segment is shield shaped, colored white or tan, contains antennal pits and retractable mandibles. The 12th segment bears two spiracles and is also lightly colored. However, the spines on this segment are outward facing.[2][13] Adult C. fontinella have black hair on their scutum and a black spot on their anipisterum.[14] Adults are typically 30 mm long and have a close resemblance to bees.

Home range and territoriality

C. fontinella are territorial insects. Males chase away intruding males while patrolling their territory by flying in figure-eight and oval patterns. Since females only fly when looking for a mate, it is important that the male controls as much high-quality territory as he can. C. fontinella are territorial and congregate above heat reflecting surfaces on roadsides and near streams. These flies are very dependent on temperature, so even though they can live in a vast array of latitudes, the climate they live in influences their prevalence throughout the year.[15]

Life history

Eggs

Egg development is slowed by temperatures below 15°C and under arid atmosphere conditions.[16] The ideal conditions for development are warm and humid, characteristic of southern climates. Stimulation from moisture and heat (often from the host passing by the egg) will cause the egg to hatch and the larva to be rubbed onto the host.[17]

Larval Instars

Once on the host, the larvae enter through the nose, mouth, eyes, anus or any open wound. Inside the body, the larva migrate and settle near the groin.[7] The larva then create a “warble” with a small hole at the top layer of skin for breathing. The backward facing spikes on the segments of the larva help to stabilize the larva. The spikes help prevent the larva from being pulled out of the host by gripping to the flesh surrounding it.[13] The larva typically emerge after the host dies (typically 3.5-4 weeks), and then burrow into the ground.[11][18][12]

Pupae

C. fontinella pupate in the ground and emerge as adults. Diapausing can occur during winter months or other general unfavorable conditions. Pupae can remain in diapause for as long as 12 months if need be. In simulated standard settings (27 degrees Celsius and an alternating day and night light schedule), pupal development typically occurs in 50 days.[19]

Adults

Adult C. fontinella live a short life without feeding. Oocyte development begins as soon as females leave the pupal stage of development. Oocyte development finishes in about 5 days. Mating can occur before oocyte development is finished. No secondary egg development occurs, likely due to the short adult life-span of C. fontinella.[19] Female C. fontinella will typically lay their eggs in vegetation, especially vegetation located near the homes/burrows of their intended hosts.[11] Adult females can lay up to 2000 total eggs.[16]

Parasitism

Migration Within the Host

After entering the body, the larva follow a distinct path within the host. If entering either through the nose, mouth or eyes, the larvae first orient themselves using the host's nasal passageway. Then the larvae travel through the upper respiratory system, making their way to the thoracic cavity. They then proceed to the abdominal cavity and eventually to the inguinal region of the host.[18] If the larvae enter the host through an open wound or the anus, they find the closest portion of the standard tract, then continue their journey as they normally would.[9]

Warbles

Once settled, the larva creates areas of swelling in the subcutaneous skin layer of their host. These swellings, known as warbles, are located between the anus and genital organs of the host. They last the same amount of time that the larva spends in its larval stage (3.5-4 weeks). The warble consists of a pore, a cavity, and a capsule. The pore serves as a breathing hole for the larva. As the larva grows, the size of the warble grows with it. Translucent yellow liquids are secreted both from the larva. The cavity is the area of the warble where the larva lives. It expands gradually as the larva grows in size. The capsule is the tissue that surrounds the cavity. The capsule starts off as thin tissue, and thickens as the larva's development continues due to natural bodily healing of the host.[9]

Effect on Individual

.jpg.webp)

Individuals infested with C. fontinella can experience anemia, leukocytosis, plasma protein imbalances, local tissue damage, and splenomegaly.[7] Infested female hosts produce fewer and smaller litters than those who are parasite-free.[20] Counterintuitively, infestation actually leads to an increase in survival time for the host, not a decrease in survival as one would expect. It's possible that this could be caused by the change in resource allocation from reproduction to body preservation, a change that is favorable for both the host’s and the C. fontinella’s survival. Interestingly, if multiple C. fontinella infest a host simultaneously, the host will instead experience a decrease in survival time.[21]

Behavioral Changes

No effect on host fecundity has been recorded within C. fontinella’s preferred host, Peromyscus leucopus. Male movement was also unaffected. However, female movement decreases when infested with C. fontinella. This suggests that P. leucopus has evolved a tolerance for infestation.[21]

Host Resistance

Resistance to infestation has been documented in hosts that have been previously infested. The resistance occurs at the entry points that have been used previously by larva as well as the genital region of the host where the larvae typically create their warbles. Nasal, oral and anal resistance cause a decrease in infestation rate when exposed to larvae of 15-30%. No resistance from repeated ocular entry occurs. Maximum antibody production from the host occurs 28 days after infestation. The resistance causes the larvae to take abnormal alternate paths within the host. These abnormal paths caused the larva to develop in atypical regions in the host.[22] The insecticide Ronnel can be used to effectively stop development of larvae by preventing the larvae from boring breathing holes in the skin of the host.[18]

Effect on Population

Infestation has varying effects on the host population’s reproductive fitness, depending on the size of the habitat and the infestation rate of C. fontinella. If the host population lives in a vast habitat with scattered areas of infestation, the reproductive rate of the host is essentially unaffected. However, in smaller habitats with higher and more uniform rates of infestation, reproductive rates can be noticeably decreased.[7][20]

Food resources

The species' host serves as the primary food source exploited for nutrients. Different species of Cuterebra prey on various species of rodents.[23] However, there have been documented cases of C. fontinella preying on several different types of rodents.[12][7][9][17][8] Peromyscus leucopus (White footed mice) is the favored host for C. fontinella. Typically 19%-33% of all P. leucopus are infested within a year.[7] Other hosts for C. fontinella include Lepus artemisia (Cottontail Rabbit), Ochrotomys nuttalli (Golden Footed Mouse),[17] Peromyscus gossypinus (Cotton Mouse),[7] Peromyscus maniculatus (Deer Mouse),[9] Liomys irroratus (Mexican Spiny Pocket Mouse)[10] and even very rarely humans.[8] The highest infestation rates occur in late summer/early fall.[11]

Mating

Adults aggregate in open, sunny areas which is where the flies find their mates.[11] However, C. fontinella do not mate in temperatures below 20°C.[15] Adult males fly 1-2 meters above the ground for up to 4 hours a day in the presence of sunlight in order to attract a mate. Once a female demonstrates her interest, the pair finds a nearby branch or leaf for stability. The female grabs the branch or leaf and the male mounts her. The pair copulates for about three minutes.[24]

Ovipositor

The ovipositor of C. fontinella is unusually short relative those of the other members of the family Oestridae. Covered by dense hairs, the ovipositor resembles a horseshoe, with two sclerite ends and a chitinous plate between them.[12]

Social behavior

Male C. fontinella fly around their territories from the time at which the temperature exceeds 20°C to the early afternoon.[15] Flight will only be initiated during sunlight but can continue during brief cloud coverage not exceeding 15 minutes. Since their flight is limited by temperature, the amount of time spent flying is dependent on the weather and temperature of the day. Female C. fontinella are only seen flying when searching for a mate. Male C. fontinella are extremely territorial. Males usually occupy a stretch of territory 17 m long along the bank of a stream. They chase most airborne intruders that travel through their territory, regardless of their species. If two males intersect in the air, they grab onto each other and tumble to the ground. Chases persist for 10-15 minutes, with the flies typically traveling 35 km.[24] C. fontinella tolerate a population density of up to 250 flies per km^2. Fly density varies depending on weather conditions and the time of the year.

Genetic identification

Genetic analysis can also be used to discriminate between species. COI and COII genes are reliable markers to differentiate between species. Using species specific markers, scientists can accurately identify the species of a botfly at any stage of life. In many cases larvae look ambiguous enough to be confused for another species, so genetic identification is very important. Hybridization between species within the genus Cuterebra has been known to occur, and can cause ambiguity within testing.[14]

Subspecies

Two subspecies that belong to the species Cuterebra fontinella include Cuterebra fontinella fontinella and Cuterebra fontinella grisea b (deer mouse bot fly).

Interactions with humans

Rare cases of C. fontinella host infestations have been reported but are not the norm. In most of these cases the larvae remain in benign locations such as the in the eye or in the subcutaneous regions within the eyelid. Occasionally, however, the larvae exploit a pathway gaining access to the tracheal-pulmonary system. Consequent symptoms in the human host include cold-like symptoms and flares-coughing patterns. The larva are exiled from the human host when the host coughs a bloody secretion containing the larva.[8][19]

Another species of bot fly called Dermatobia hominis commonly infests humans in Central and South America. Most cases of human infestation within North America are caused by the victim traveling into regions where D. hominis are present. As of 1989, there were 55 documented cases of myiasis caused by species within the Cuterebra genus. Treatment typically consists of removal of the larva and then prevention of secondary bacterial infections. If the warble is accessible, a specialist can remove the larva by depositing petroleum jelly over the breathing hole of the parasite; this causes the larva to emerge for air and enable easier removal by the specialist. Larvae within or near the eye will sometimes require surgery for removal. Larvae that die within the vitreous humor of the eye do not need to be removed, they will be broken down and absorbed by natural chemical processes within the host.[25]

Conservation

A major threat to infestation rates of C. fontinella is pasture burning. When soil reaches high temperatures, pupating larvae die, and ash produced during burning causes microclimate changes. These changes contribute significantly to increasing greater congregation of C. fontinella.[26]

Data sources: i = ITIS,[1] c = Catalogue of Life,[3] g = GBIF,[4] b = Bugguide.net[5]

References

- "Cuterebra fontinella Report". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- Leonard, AB (1933). "Notes on larvae of Cuterebra sp.(Diptera: Oestridae) infesting the Oklahoma cottontail rabbit". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 36: 270–274. doi:10.2307/3625368. JSTOR 3625368.

- "Cuterebra fontinella species details". Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- "Cuterebra fontinella". GBIF. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- "Cuterebra fontinella Species Information". BugGuide.net. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- "Cuterebra fontinella Overview". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- Durden LA (1995). "Bot Fly (Cuterebra fontinella fontinella) Parasitism of Cotton Mice (Peromyscus gossypinus) on St. Catherines Island, Georgia". The Journal of Parasitology. 81 (5): 787–790. doi:10.2307/3283977. JSTOR 3283977. PMID 7472877.

- Scholten T, Chrom VH (1979). "Myiasis due to Cuterebra in humans". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 120 (11): 1392–1393. PMC 1819321. PMID 455186.

- Cogley TP (1991). "Warble development by the rodent bot Cuterebra fontinella (Diptera: Cuterebridae) in the deer mouse". Veterinary Parasitology. 38 (4): 275–288. doi:10.1016/0304-4017(91)90140-Q. PMID 1882496.

- Slansky F (2006). "Cuterebra bot flies (Diptera: Oestridae) and their indigenous hosts and potential hosts in Florida". Florida Entomologist. 89 (2): 152–160. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2006)89[152:CBFDOA]2.0.CO;2.

- Wolf M, Batzli GO (2001). "Increased prevalence of bot flies (Cuterebra fontinella) on white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) near forest edges". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 79: 106–109. doi:10.1139/z00-185.

- Hadwen S (1915). "A description the egg and ovipositor of Cuterebra fontinella, Clark (Cottontail Bot.)". Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia. 5: 88–91.

- Colwell, DD (1986). "Cuticular sensilla on newly hatched larvae of Cuterebra fontinella Clark (Diptera: Cuterebridae) and Hypoderma spp.(Diptera: Oestridae)". International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology. 15 (5): 385–392. doi:10.1016/0020-7322(86)90032-2.

- Noël S, et al. (2004). "Molecular identification of two species of myiasis‐causing Cuterebra by multiplex PCR and RFLP". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 18 (2): 161–166. doi:10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00489.x. PMID 15189241. S2CID 20399393.

- Hunter D, Webster J (1973). "Aggregation behavior of adult Cuterebra grisea and C. tenebrosa (Diptera: Cuterebridae)". The Canadian Entomologist. 105 (10): 1301–1307. doi:10.4039/Ent1051301-10.

- Catts EP (1982). "Biology of New World Botflies: Cuterebridae". Annual Review of Entomology. 27: 313–338. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.27.010182.001525.

- Jennison CA, Rodas LR, Barrett GW (2006). "Cuterebra fontinella parasitism on Peromyscus leucopus and Ochrotomys nuttalli". Southeastern Naturalist. 5 (1): 157–168. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2006)5[157:CFPOPL]2.0.CO;2.

- Gingrich EG (1981). "Migratory Kinetics of Cuterebra Fontinella (Diptera: Cuterebridae) in the White-Footed Mouse, Peromyscus leucopus". The Journal of Parasitology. 67 (3): 398–402. doi:10.2307/3280563. JSTOR 3280563. PMID 7264830.

- Scholl PJ (1991). "Gonotrophic Development in the Rodent Bot Fly Cuterebra fontinella (Diptera: Oestridae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 28 (3): 474–476. doi:10.1093/jmedent/28.3.474. PMID 1875379.

- Burns CE, Goodwin BJ, Ostfeld RS (2005). "A prescription for longer life? Bot fly parasitism of the white‐footed mouse". Ecology. 86 (3): 753–761. doi:10.1890/03-0735.

- Miller DH, Getz LL (1969). "Botfly Infections in a Population of Peromyscus Leucopus". Journal of Mammalogy. 50 (2): 277–283. doi:10.2307/1378344. JSTOR 1378344.

- Pruett JH, Barrett CC (1983). "Development by the laboratory rodent host of humoral antibody activity to Cuterebra fontinella (Diptera: Cuterebridae) larval antigens". Journal of Medical Entomology. 20 (2): 113–119. doi:10.1093/jmedent/20.2.113. PMID 6842520.

- Sabrosky CW (1986). "North American Species of Cuterebra, The Rabbit and Rodent Bot Flies (Diptera Cuterebridae)". Ent. Soc. Amer. 11, vii: 1–240.

- Shiffer, CN (1983). "Aggregation behavior of adult Cuterebra fontinella (Diptera: Cuterebridae) in Pennsylvania, USA". Journal of Medical Entomology. 20 (4): 365–370. doi:10.1093/jmedent/20.4.365.

- Baird JK, Baird CR, Sabrosky CW (1989). "North American cuterebrid myiasis: report of seventeen new infections of human beings and review of the disease". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 21 (4): 763–772. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70252-8. PMID 2681284.

- Boggs JF, Lochmiller RL, McMurry ST, Leslie DM, Engle DM (1991). "Cuterebra infestations in small-mammal communities as influenced by herbicides and fire". Journal of Mammalogy. 72 (2): 322–327. doi:10.2307/1382102. JSTOR 1382102.

Further reading

- Arnett, Ross H. Jr. (2000). American Insects: A Handbook of the Insects of America North of Mexico (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0212-9.

- McAlpine, J.F.; Petersen, B.V.; Shewell, G.E.; Teskey, H.J.; et al. (1987). Manual of Nearctic Diptera. Research Branch Agriculture Canada. ISBN 978-0660121253.

- T., Pape (2006). Colwell, D.D. (ed.). "Phylogeny and evolution of bot flies". The Oestrid Flies: Biology, Host-parasite Relationships, Impact and Management: 20–50. doi:10.1079/9780851996844.0020. ISBN 9780851996844.

External links

- "Diptera.info". Retrieved 2018-03-20.