Cuttlebone

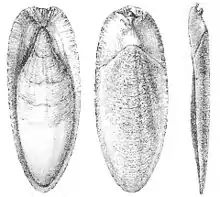

Cuttlebone, also known as cuttlefish bone, is a hard, brittle internal structure (an internal shell) found in all members of the family Sepiidae, commonly known as cuttlefish, within the cephalopods. In other cephalopod families it is called a gladius.

Cuttlebone is composed primarily of aragonite. It is a chambered, gas-filled shell used for buoyancy control; its siphuncle is highly modified and is on the ventral side of the shell.[2] The microscopic structure of cuttlebone consists of narrow layers connected by numerous upright pillars.

Depending on the species, cuttlebones implode at a depth of 200 to 600 metres (660 to 1,970 ft). Because of this limitation, most species of cuttlefish live on the seafloor in shallow water, usually on the continental shelf.[3]

The largest cuttlebone belongs to Sepia apama, the giant Australian cuttlefish, which lives between the surface and a maximum depth of 100 metres.

Human uses

In the past, cuttlebones were ground up to make polishing powder, which was used by goldsmiths.[4] The powder was also added to toothpaste,[5] and was used as an antacid for medicinal purposes[4] or as an absorbent. They were also used as an artistic carving medium during the 19th[6][7] and 20th centuries.[8][9][10][11][12]

Today, cuttlebones are commonly used as calcium-rich dietary supplements for caged birds, chinchillas, hermit crabs, reptiles, shrimp, and snails. These are not intended for human consumption. [13]

Lime production

As a carbonate-rich biogenic raw material, cuttlebone has potential to be used in the production of calcitic lime.[14]

Jewelry making

Because cuttlebone is able to withstand high temperatures and is easily carved, it serves as mold-making material for small metal castings for the creation of jewelry and small sculptural objects.[lower-alpha 1]

It can also be used in the process of pewter casting, as a mould.

Internal structure

- 3D visualisation of a Sepia cuttlebone by industrial micro-computed tomography

3D view of part of a cuttlebone at low resolution.

3D view of part of a cuttlebone at low resolution. Overview of a part at high resolution, about 5 µm/voxel.

Overview of a part at high resolution, about 5 µm/voxel. Higher magnification.

Higher magnification. Detailed view at very high magnification. Wall thickness of the vertical structures is about 10 µm.

Detailed view at very high magnification. Wall thickness of the vertical structures is about 10 µm.

- Flight through the corresponding tomographic image stacks

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuttlebone. |

Footnotes

- Jewelers prepare cuttlebone for use as a mold by cutting it in half and rubbing the two sides together until they fit flush against one another. Then the casting can be done by carving a design into the cuttlebone, adding the necessary sprue, melting the metal in a separate pouring crucible, and pouring the molten metal into the mold through the sprue. Finally, the sprue is sawed off and the finished piece is polished.

References

- Fuchs, D.; Engeser, T.; Keupp, H. (2007). "Gladius shape variation in coleoid cephalopod Trachyteuthis from the upper Jurassic nusplingen and Solnhofen plattenkalks" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (3): 575–589.

- Rexfort, A.; Mutterlose, J. (2006). "Stable isotope records from Sepia officinalis — a key to understanding the ecology of belemnites?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 247 (3–4): 212–212. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.247..212R. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.04.025.

- Norman, M.D. (2000). Cephalopods: A world guide. Conch Books.

- "Uses for cuttlebone. The time when it was used as a medicine (1912)". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Do you know this?". The World's News. 8 July 1950. p. 26. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Wesleyan anniversary". Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser. 17 October 1872. p. 2. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Carnival at Norwood". Evening Journal. 24 October 1898. p. 3. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Eleanor Barbour's pages for country women". Chronicle. 16 July 1942. p. 26. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Note book cuttlefish". The Register News-Pictorial. 17 May 1930. p. 3S. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Models from cuttle-fish". The Age. Interesting Hobbies. 30 June 1950. p. 5S. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Back to semaphore celebrations". Port Adelaide News. 13 December 1929. p. 3. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Out among the people". The Advertiser. 12 May 1943. p. 6. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Norman, M.D.; Reid, A. (2000). A Guide to Squid, Cuttlefish, and Octopuses of Australasia. CSIRO Publishing.

- Ferraz, E.; Gamelas, J.A.F.; Coroado, J.; Monteiro, C.; Rocha, F. (20 July 2020). "Exploring the potential of cuttlebone waste to produce building lime". Materiales de Construcción. 70 (339): 225. doi:10.3989/mc.2020.15819. ISSN 1988-3226.

- Neige, P. (2003). "Combining disparity with diversity to study the biogeographic pattern of Sepiidae" (PDF). Berliner Paläobiologische Abhandlungen. 3: 189–197.