Cyclura cychlura inornata

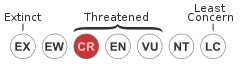

Cyclura cychlura inornata, the Allen Cays rock iguana or Allen Cays iguana, is a subspecies of the northern Bahamian rock iguana that is found on Allen's Cay and adjacent islands in the Bahamas. Its status in the IUCN Red List is critically endangered, with an estimated wild population of 482–632 animals.[1]

| Cyclura cychlura inornata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cyclura cychlura inornata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Cyclura |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. c. inornata |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cyclura cychlura inornata | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Taxonomy

Cyclura cychlura inornata is one of three subspecies of the Northern Bahamian rock iguana, the others being the Andros Island iguana (C. c. cychlura) and the Exuma Island iguana (C. c. figginsi).[3] It was found to be genetically indistinct from C. c. figginsi further south down the chain of the Exuma Islands. The different populations were likely one unbroken one 18,000 years ago during the last ice age, when the islands of the chain were likely all joined together in one large island.[4]

Description

The Allen Cays rock iguana is a large rock iguana of which the localised population on Allen's Cay attains a total length of close to 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in).[1][5][6] The iguana is normally half the size and a sixth the weight of those on Allen's Cay.[1] Its coloration is dark-gray to black, with yellowish green or orange tinged scales on the legs, dorsal crest, and the head. When the animal matures, the yellow coloration changes to a bright reddish orange color in contrast to the animals darker striped body and black feet.

This species, like other species of Cyclura, is sexually dimorphic; males are larger than females, and have larger femoral pores on their thighs, which are used to release pheromones.[7][8]

Distribution

This rock iguana subspecies is endemic to the northern Exuma Island chain in the Bahamas.[5] Before the 1990s, it was restricted to only the uninhabited Leaf Cay and U Cay, but it then began to colonise neighbouring Allen's Cay and other nearby islands such as Flat Rock Reef Cay.[6] It arrived on these islands perhaps swimming or floating the distance in some cases, or perhaps helped by humans.[9] Small numbers of up to five animals are sometimes found on the tiny surrounding islets. It was purposely spread to Alligator Cay thirty kilometres to the south, and from there appears to have spread to Narrow Water Cay and Warderick Wells Cay. The IUCN red list assessment of 2018 states most of the introductions to other islands are human assisted. Research at genetic divergence in the different populations found some discernible genetic difference between the U and Leaf Cay populations, but also evidence of recent admixture blamed on unauthorised human introductions between islands. Leaf Cay appears the source for all the introductions to other islands.[1]

Ecology

It is found in low, open forest, coastal shrubland and along beaches in elevations from sea level to 10m.[1] The forests here can reach to seven metres high. From December through April there is a cooler dry season.[10] Among the restricted amount of plant species found growing on its islands are Borrichia arborescens, Bumelia americana, Casasia clusiifolia, Conocarpus erectus, Coccoloba uvifera, Drypetes diversifolia, Eugenia foetida, Guaiacum sanctum, Ipomoea indica, Jacquinia keyensis, Leucothrinax morrisii, Manilkara bahamensis, Pithecellobium keyense, Rhachicallis americana, Solanum bahamense, Suriana maritima, Sesuvium portulacastrum, Sophora tomentosa, Thalassia testudinum and Uniola paniculata.[9] 48 species of plant are said to grow on Leaf Cay. On Alligator Cay there are 24 species of plant of which the most abundant are Borrichia arborescens, Cyperus sp., Guapira discolor, Pseudophoenix sargentii and Rhachicallis americana. Others are similar to the other Cays, but there is more mangrove here, as well as an Opuntia sp. and Erithalis fruticosa.[10] There are only a few introduced species of plants, but there are some ornamentals such as palms. It requires areas for nesting with a layer of sand of at least half a metre deep.[1]

The cays where it lives have a type of native night heron that will occasionally snack on a baby iguana.[1][6]

It is diurnal, spending nights in 'retreats' under the leaves of thatch palms, in tunnels they sometimes dig and sometimes in the open.[1] It also uses crevices and holes in limestone rocks as retreats and will congregate in areas rich in these.[10] Outside of the mating season, male rock iguanas have dominance hierarchies rather than strictly defended territories like cyclura from other islands. This has been attributed to the regular food supply from tourists feeding the lizards on the beach causing a disruption in their social structure.[11] However, a 2000 report demonstrated this theory tested on Alligator Cay, which is free from tourists, and also found a low amount of male-to-male aggression in this species. The author of that study pointed to the small nature of the inhabited islands as a reason for reduced aggression.[12]

Diet

All iguanas except the largest adults climb into the vegetation to feed, including up the smooth boles of thatch palms.[1] Even adults have been found 2 m (6 ft 7 in) up in a Pseudophoenix palm to eat the flower buds.[10] They are primarily herbivorous, feeding on fruits, leaves, and flowers of most available plants. Individuals can survive on very tiny islands from the available plants.[1] On Alligator Cay the population eats mostly Rhachicallis americana and Suriana maritima, the former is more common and is eaten more, but the lizards show a preference for the latter, which is relatively much more uncommon on the island.[10][12] Two studies in the remains of their faeces found occasional crab claws, insects, molluscs and fledgling birds, and they have been observed to be occasionally carnivorous.[1] They also have been found to eat their shed skin. On Alligator Cay three plants were not observed to be eaten: Hymenocallis arenicola and Strumpfia maritima, and the mangrove Rhizophora mangle. More than a quarter of the faeces were made up of fruit. The iguana ate the large fruit of Casasia clusiifolia and Manilkara bahamensis, as well as the small fruit of the sea grape Coccoloba uvifera, and the palms Coccotrinax argentata and Pseudophoenix sargentii. Casasia fruit are produced throughout the year and represented 9.6% of the total faecal matter, the second most prevalent item. The iguanas feed on more leaves when they are forced to during the cool and dry season.[10]

Biologists Kristen Richardson, John Iverson and Carolyn Kurle investigated the diets of the Allen Cays Rock Iguanas on islands in the Bahamas. Their 2019 study made use of carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis to estimate iguana diets in order to explain why iguanas on Allen's Cay were ~2 times longer and ~6 times heavier than the same subspecies on nearby Leaf Cay and U Cay, the populations being only a generation removed and separated by a 300 m (980 ft) channel. They had hypothesized that the gigantic iguanas were eating shearwater carcasses killed by mice and barn owls, but they found no evidence for that hypothesis. Instead they determined that their gigantism was due to their consumption of plant material containing more nutrients than the plants on the other cays. The added nutrients came from the ocean in the form of seabird guano; the largest colony of Audubon's shearwaters (Puffinis iherminieri) are located on Allen's Cay. None of the other cays have large populations of seabirds and so are missing the extra amounts of nutrients that arrive in the form of guano on Allen's Cay. Their evidence strongly supports that these iguanas are herbivores and the giants on Allen Cay are so large because their plants contain higher levels of nutrients from seabird guano.[6][9]

Tourists often feed the iguanas human food items on Leaf Cay[9] and sometimes U Cay.[1] The iguanas have come to expect to be fed and may congregate in large numbers awaiting the tourists.[10]

Mating

Mating occurs in May, and eggs are usually laid in mid-June to mid-July, in nests excavated in sand. The females migrate to suitable areas to nest.[1] On the newly colonised Allen's Cay there is no sand on the jagged honeycomb limestone beaches, and the iguanas have never bred there.[6][9] The subspecies previously bred on only the two original islands U and Leaf Cay, but on the islands of Alligator Cay and Flat Rock Reef Cay there are suitable breeding sites.[1]

Only one in three females nests in a given year, although the largest females nest annually. One to ten eggs are laid; larger females lay more eggs than do smaller females. Hatching occurs with a success rate of 79% in late September and early October after an incubation 80–85 days at nest temperatures of 31 °C (88 °F).[1]

Conservation

Status

The IUCN assessed the population to be endangered in 1996 and 2000, but in 2018 it assessed that the populations had become critically endangered.[1]

In the early 1900s the population was almost wiped out, but had increased to some 150 iguanas by 1970 on the only two islands were it bred. In 1982, this had increased to a bit over 200 animals. In the early 1980s the population was growing at some 20% annually, and it had recovered by the end of the century to the limit of the carrying capacity of its original islands.[1] In 2000, it was estimated that the current global population was less than 1,000 and it was said to be declining,[5] although it was actually increasing. In 2018 the population was assessed to be 482–632 (mature adult) individuals, with 482 being the amount of mature adult iguanas on U and Leaf Cay in 2016 based on recapture counts. This number does not include over 150 adult iguanas found on islands where it believed they cannot breed.[1] The population on Allen's Cay was at 20–25 for a number of decades according to Iverson, but it was reduced to ten individuals in 2013 indirectly due to bird conservation activities.[6][9] In the 1990s, a number of iguanas were moved to nearby islands.[1] Iverson and P. Hall, a warden of Exumas Cays Land and Sea Park moved only eight sub-adults to Alligator Cay between 1988 and 1990, of which at least seven had survived ten years later, and these had increased to between 75 and 90 individuals in 1999 based on recapture analysis of 28 caught and tagged iguanas during four visits. Mostly larger lizards were caught and it was expected there were many more juveniles, and the island had not reached carrying capacity.[10][12] According to the IUCN the population declined over the next decade due to hurricane damage of the vegetation and emigration to the nearby island of Narrow Water Cay. Hines reported seeing 28 iguanas on Alligator Cay and an estimated 38 iguanas on Narrow Water Cay in 2013, and found that apparently some iguanas had successfully emigrated to nearby Warderick Wells Cay. The Flat Rock Reef Cay population was introduced in the mid-1990s, apparently without authorisation. It rapidly increased to around 200 individuals by 2012, although the IUCN claimed in 2018 that the island would not sustain this population due to its low carrying capacity.[1]

Threats

The primary threat to this species according to IUCN in 2018 is ecotourism and the feeding of the lizards by tourists. A number of tour operators and sometimes private yachts moor at either of the islands, bringing a few hundred tourists a day to see the lizards on both Leaf and U Cay. Tourists may transmit diseases and parasites and sometimes feed the iguanas unnatural food such as foreign fruit, bread, brownies or meat which is believed to contribute to health problems for the lizards such as faecal impaction and high levels of cholesterol. Despite dogs and cats being banned, tourists continue to bring their pets and a single loose dog could eliminate a population. Furthermore the IUCN alleges that tour operators may have moved some of the largest lizards off to other islands where they cannot scare the tourists, because they found a tagged individual on and islet eight kilometres away from where he was tagged, and they state large iguanas appear to be becoming rarer in the population.[1] The iguanas are the primary tourist attraction to this area of the Bahamas.[12]

A century ago, in the early 1900s, the Allen Cays rock iguana was almost wiped out due to being hunted for food by locals.[1] As of 2003 the animals were still said to be hunted for food and captured for sale in the pet trade.[13] In 2018 this was repeated by the IUCN, although there is no documentation that this has occurred.[1]

Recovery efforts

Like all Bahamian rock iguanas, this species is protected in the Bahamas under the Wild Animals Protection Act of 1968.[5] It is listed in Appendix I of the CITES convention.[1] Allen's Cay was formerly over-run by the common house mouse (Mus musculus), an invasive species, and these were in their turn attracting barn owls (Tyto alba) from neighbouring islands.[6] In May 2012, Island Conservation and the Bahamas National Trust worked together to remove invasive house mice from Allen's Cay to protect the Audubon's shearwater and hopefully also native species such as the Allen Cay rock iguana and the Bahama yellowthroat.[14][15] As it was feared the Allen Cay rock iguana might eat the rodenticide used to rid the island of the mice, eighteen were transplanted to nearby Flat Rock Reef Cay, where another small population already existed.[6] Sixteen of these had starved to death by 2013.[6][9] It is now thought this was because the plants on Flat Rock Reef Cay lacked the extra nutrients found on Allen's Cay. After this eight iguanas survived on Allen's Cay, and including the two from Flat Rock Reef Cay there are now ten iguanas thought to be left on the island.[6] In 2012, Iverson had begun a project to fill a small sinkholes on the island with sand to create suitable breeding ground.[1][6]

The population on Alligator Cay was released there as part of a conservation translocation program.[1][10] It was seen as quite successful in 2001.[10] Alligator Cay and surrounding islands are part of the national Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park.[10][12]

There are no captive breeding programmes which have been undertaken in this subspecies.[1]

References

- Iverson, John B.; Grant, T. D.; Buckner, S. (2018). "Cyclura cychlura ssp. inornata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Cyclura cychlura, The Reptile Database

- Hollingsworth, Bradford D. (2004), "The Evolution of Iguanas: An Overview of Relationships and a Checklist of Species", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 35–39, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Malone, Catherine L.; Wheeler, Tana; Taylor, Jeremy F.; Davis, Scott K. (November 2000). "Phylogeography of the Caribbean Rock Iguana (Cyclura): Implications for Conservation and Insights on the Biogeographic History of the West Indies". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 17 (2): 269–279. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0836. PMID 11083940. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- D. Blair & West Indian Iguana Specialist Group (2000). "Cyclura cychlura inornata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000. Retrieved February 23, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tennenhouse, Erica (20 May 2019). "Solved: How the 'Monstrous' Iguanas of the Bahamas Got So Darn Big". Atlas Obscura Daily Newsletter. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- De Vosjoli, Phillipe; David Blair (1992), The Green Iguana Manual, Escondido, California: Advanced Vivarium Systems, ISBN 1-882770-18-8

- Martins, Emilia P.; Lacy, Kathryn (2004), "Behavior and Ecology of Rock Iguanas, I: Evidence for an Appeasement Display", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 98–108, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Richardson, Kristen M.; Iverson, John B.; Kurle, Carolyn M. (8 March 2019). "Marine subsidies cause gigantism of iguanas in the Bahamas" (PDF). Oecologia. 189: 1005–1015. doi:10.1007/s00442-019-04366-4. PMID 30850885. S2CID 71717155. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Knapp, Charles R. (June 2001). "Status of a Translocated Cyclura Iguana Colony in the Bahamas" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 35 (2): 239–248. doi:10.2307/1566114. JSTOR 1566114. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Iverson, John; Smith, Geoffrey; Pieper, Lynne (2004), "Factors Affecting Long-Term Growth of the Allen Cays Rock Iguana in the Bahamas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, p. 176, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Knapp, Charles R. (2000). "Home Range and Intraspecific Interactions of a Translocated Iguana Population (Cyclura cychlura inornata Barbour and Noble)". Caribbean Journal of Science. 36 (3–4): 250–257. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Iverson, John (21 May 2003), Results of Allen Cays Iguana study (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Dept. of Biology, Earlham College, archived from the original (– Scholar search) on April 10, 2005

- "Native Iguanas and Shearwaters saved from invasive mice on Allen Cay". Bahamas National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Allen Cay Restoration Project". Island Conservation. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

| Wikispecies has information related to Cyclura cychlura inornata. |