Dan Dworsky

Daniel Leonard Dworsky (born October 4, 1927) is an American architect. He is a longstanding member of the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows. Among other works, Dworsky designed Crisler Arena, the basketball arena at the University of Michigan named for Dworsky's former football coach, Fritz Crisler. Other professional highlights include designing Drake Stadium at UCLA, the Federal Reserve Bank in Los Angeles and the Block M seating arrangement at Michigan Stadium. He is also known for a controversy with Frank Gehry over the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

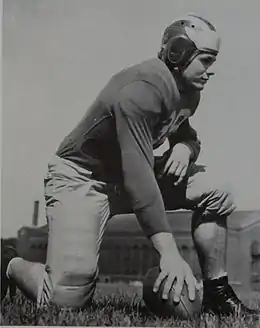

Dworsky from 1948 Michiganensian | |

| Born: | October 4, 1927 Minneapolis |

|---|---|

| Career information | |

| Position(s) | Linebacker |

| College | University of Michigan |

| Career history | |

| As player | |

| 1949 | Los Angeles Dons |

Previously, Dworsky was an American football linebacker, fullback and center who played professional football for the Los Angeles Dons of the All-America Football Conference in 1949, and college football for the Michigan Wolverines from 1945 to 1948. He was an All-American on Michigan's undefeated national championship teams in 1947 and 1948.

College football at the University of Michigan

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1927, Dworsky lived in the Twin Cities and Sioux Falls, South Dakota before attending the University of Michigan.[1] Dworsky was a four-year starter for Fritz Crisler's Michigan Wolverines football teams from 1945 to 1948. He played linebacker, fullback, and center for the Michigan Wolverines and was a key player on the undefeated 1947 and 1948 Michigan football teams that won consecutive national championships. The 1947 team, anchored by Len Ford, Alvin Wistert, Dworsky and Rick Kempthorn, has been described as the best team in the history of Michigan football.[2] Dworsky won a total of six varsity letters at Michigan, four in football and two in wrestling where he competed in the heavyweight division. Dworsky is among the famous Jews in football,[3] and has been extensively profiled in encyclopedic Jewish publications.[4] Dworsky married the former Sylvia Ann Taylor on August 10, 1957. The couple has three children: Douglas, Laurie and Nancy. They reside in Los Angeles.[5]

1947 season

The 1947 Michigan Wolverines football team went 10–0 and outscored their opponents 394 to 53. Dworsky led a defensive unit that gave up an average of 5.3 points per game and shut out Michigan State (55–0), Pitt (60–0), Indiana (35–0), Ohio State (21–0), and USC (49–0).[6] He also played fullback and center for the 1947 team and was named a third team All-American by the American Football Coaches Association. In a 1988 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Dworsky described the 1947 team's defensive scheme as follows: "We were an intelligent team and we had some complex defenses, the nature of which you see today. I called the defensive signals and we would shift people, looping, or stunting."[7]

After going undefeated and winning the Big Ten championship, Michigan was invited to Pasadena to face the USC Trojans in the 1948 Rose Bowl—the Wolverines' first bowl game since 1901. Just before Christmas, the team boarded a train in Ann Abor for a three-day trip across the country. With little to do on the train, Alvin Wistert recalled that Dworsky entertained the team with music. "Dan Dworsky was a piano player. We'd gather around and sing. There was a piano in the last car."[8]

After the long trip, the Wolverines beat the Trojans 49–0. Dworsky recalled that the coaching staff did an excellent job of scouting the Trojans. "When we went to the Rose Bowl, we had USC down pat. We knew their system as well as they did."[7] The Trojans gained only 91 yards rushing and 42 yards passing, moving past midfield only twice. Dworsky played center during the Rose Bowl, blocking USC's All-American tackle (and future Los Angeles city councilman), John Ferraro.[7]

In Dworsky's collegiate days, the final national rankings were determined before the bowl games.[4] At the end of the regular season in 1947, Michigan was ranked No. 2 behind Notre Dame, but after defeating USC 49–0 in the Rose Bowl, the Associated Press held a special poll, and Michigan replaced Notre Dame as the national champion by a vote of 226 to 119. Dworsky later noted, "Notre Dame still claims that national championship and so do we."[7]

1948 season

The 1948 Michigan Wolverines football team went 9–0 and outscored their opponents 252 to 44. The defensive unit led by Dworsky held its opponents to just 4.9 points per game, including shutouts against Oregon (14–0), Purdue (40–0), Northwestern (28–0), Navy (35–0), and Indiana (54–0).[9] The 1948 Wolverines finished the season ranked No. 1 by the AP, but Big Ten Conference rules prohibited a team from playing in the Rose Bowl two years in a row. Dworsky did, however, play in the 1948 Blue–Gray All Star game.

Relationship with Fritz Crisler

Dworsky was a four-year starter under Michigan's legendary coach, Fritz Crisler. Dworsky later said that Crisler's "real genius" was in blending all the elements. The 1947 championship team included several older veteran players who had returned from military service. Dworsky recalled: "About half of us were 18-year old kids, and half were veterans. We had guys who were serious guys and guys who were excitable. Fritz struck a balance, so we never had to be pushed, but we never lost our focus either."[10]

Dworsky recalled: "Crisler was not only an intellectual in strategy, but also in the way he ran practices.... He ran practices rigidly and we called him 'The Lord'. He would allow it to rain, or not. He was a Douglas MacArthur-type figure, handsome and rigid.... I sculpted him and gave him the bust in 1971."[7] Dworsky also kept another bust of Crisler in his office.[7]

Professional football with the Los Angeles Dons

In 1949, Dworsky was the first round draft pick of the Los Angeles Dons of the All-America Football Conference. The Dons were the first professional football team in Los Angeles. Dworsky played eleven games with the Dons in 1949, his only season in professional football. Dworsky played linebacker and blocking back for the Dons and had one interception and one kick return for 14 yards.[11] The AAFC disbanded after the 1949 season, and Dworsky turned down an offer from the Pittsburgh Steelers to return to the University of Michigan where he graduated in 1950 with a degree in architecture.[12] Dworsky later noted: "It was a toss-up whether I would become a pro football player or an architect. Being a linebacker is good conditioning for a young designer. You learn to block the bull coming at you from all sides."[13]

Career as an architect

Overview of Dworsky's practice

After receiving his degree in architecture in 1950, Dworsky moved to Los Angeles and served as an apprentice in the early 1950s with prominent local early modernists William Pereira, Raphael Soriano, and Charles Luckman.[13] In 1953, Dworsky began his own architecture firm in Los Angeles, known as Dworsky Associates. The firm grew into one of the most prominent architectural firms in California, creating major public buildings in California. Dworsky Associates won the 1984 Firm of the Year Award from the California Council of the American Institute of Architects.[13] In September 2000, Dworsky Associates merged with CannonDesign and ceased to operate as an independent firm.[14]

Architectural style

Dworsky belongs to the generation of post-World War II modernists that took its cues from the 1920s German Bauhaus and the French-Swiss master Le Corbusier.[13] In 1988, Dworsky noted: "I am most intrigued by the essential mystery of architecture. For me, built space will always be a kind of theater, a stage on which life is played, and played out. That's why I keep on being an architect.[13] Asked what inspires his architecture, Dworsky said he draws from the "solid, resolved concepts" of modern designers such as Le Corbusier and Marcel Bruer, while being encouraged on occasion to experiment by such "new wave" designers as Frank Gehry and Eric Owen Moss.[15]

Crisler Arena and the Block "M"

Dworsky's first major commission was to design a basketball arena for his alma mater, the University of Michigan. The members of the 1947 Michigan Wolverines football team had reunions with Fritz Crisler every five years in Ann Arbor,[7] and it was at one of those reunions that Crisler (by then the school's athletic director) gave Dworsky one of his big breaks, asking him to design the arena. Built in 1967, the arena was named Crisler Arena, as a tribute to the coach. Dworsky's design of the arena was well received and was said to demonstrate "his ability to combine majesty of scale with human accessibility".[1] The roof of Crisler Arena is made of two plates, each weighing approximately 160 tons. The bridge-like construction allows them to expand or contract given the change of seasons or the weight of the snow.[16] Crisler Arena remains the home of Michigan's basketball team and houses memorabilia and trophies from all Wolverine varsity athletic teams.

In 1965, the wooden benches at Michigan Stadium were replaced with blue fiberglass benches. Dworsky designed a yellow "Block M" for the stands on the eastern side of the stadium, just above the tunnel.[17]

Drake Stadium at UCLA

After his work on Crisler Arena, Dworsky was commissioned by UCLA to design a track and field stadium on the university's central campus. Dworsky designed the stadium, known as Drake Stadium. Since its inaugural meet on February 22, 1969, the stadium has been the site of numerous championship meets, including the National AAU track & field championships in 1976, 1977, and 1978. It is also used each year for special campus events, such as the annual UCLA Commencement Exercises in June.[18]

Major works

The major works credited to Dworsky and his firm include the following:

- The Jerry Lewis Neuromuscular Research Center at UCLA (1979).[19]

- The Tom Bradley International Terminal at Los Angeles International Airport (1984).[13]

- A 35 acres (0.055 sq mi; 0.142 km2) planned community complex for the California School for the Blind in Fremont, California.[1] The design won a merit award from the California AIA.[15]

- The Theater Arts Building at California State University Dominguez Hills. Dworsky cited the theater as one of his favorite projects.[1] Photograph of Building

- The Angelus Plaza residential complex in the Bunker Hill area of downtown Los Angeles (1982) Photograph of Building

- The Ventura County Jail.[20]

- The Los Angeles Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank located at Grand Avenue and Olympic Boulevard in downtown Los Angeles (1987).[21] Dworsky Associates won several awards for its design of the 304,000 square feet (28,200 m2), $50 million building.[22] Photograph of Building

- The Northrop Electronics Division Headquarters in Hawthorne, California. Dworsky Associates received a Gold Nugget Grand Award for Best Commercial Office Building and top honors in the Crescent Architecture Awards competition for the design.[23][24]

- The Kilroy Airport Center in Long Beach, California, a complex of office buildings fronting the 405 Freeway with direct runway access to the Long Beach Airport for private aircraft (1987).[25] Photograph of Building

- The Westwood Terrace building on Sepulveda Boulevard in West Los Angeles, California occupied by New World Entertainment.[26]Photograph of Building

- The 20-story City Tower in Orange, California near the intersection of the Garden Grove (22) and Santa Ana (5) freeways in Orange County.[27] Photograph of Building

- The Home Savings building on Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks, California.[28]

- The Metropolitan, a 14-story upscale rental complex in downtown Los Angeles’ South Park area.[29]

- The Van Nuys Municipal Court building in Van Nuys, California.[30] Dworsky Associates received the Kaufman & Broad Award for Outstanding New Public or Civic Project for the design.[31]

- The Federal Office Building in Long Beach, California. Dworsky Associates was awarded a 1992 Design Award from the General Services Administration for its design of the federal building.[32]

- The renovation of the Carnation Building at 5055 Wilshire Boulevard in Hollywood. The renovated building was occupied by The Hollywood Reporter, Billboard, and other entertainment industry companies.[33]

- The Beverly Hills Main Post Office in Beverly Hills, California. Dworsky Associates received a Beautification Award from the Los Angeles Business Council for the design.[34]

- The San Joaquin County Jail in French Camp, California. Shortly after the prison opened, six prisoners escaped after cutting through a one-inch bar in the dayroom with a hacksaw. The prison break led to finger-pointing among the construction firm, the architect, and the prison guards over who was responsible for the lapse in security.[35]

- The UC Riverside Alumni and Visitors Center (1996). Photographs

- The Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza, a project on which Dworsky Associates teamed with New Mexico architect Antoine Predock. The New Mexico chapter of the AIA gave Predock and Dworsky Associates an award in 1996 for their work on the Civic Arts Plaza.[36]

- The Calexico Port of Entry building in Calexico, California. The innovative design won the highest award from the California AIA,[37] and it won a Presidential Design Award from President Bill Clinton.[38] Photos and Drawings of Award Winning Calexico Port of Entry

- Beckman Hall at Chapman University in Orange, California (1999). Photograph of Building

- The Lloyd D. George Federal Courthouse in Las Vegas, Nevada (2000). Photographs of Courthouse

- The Hollywood-Highland station on the Metro B Line in the heart of Hollywood.[39] Photograph of Station

Awards and honors

Dworsky has received numerous national, regional and community awards for design excellence, including the following:

- Dworsky's numerous award-winning projects in his first 14 years of practice led to his election to the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows at the early age of 41.[1]

- Gold Medal Award from the Los Angeles Chapter of the American Institute of Architects[1]

- Lifetime Achievement Award for Distinguished Service from the American Institute of Architects, California Council, awarded in 2004. In granting the award, the Council noted that Dworsky had "made a major, positive impact on California architecture" and his "strong, simple sculpted work has provided a compelling statement for California architecture the past half century".[1]

- He was voted one of the twelve most distinguished architects in Los Angeles.[1]

- Dworsky Associates won the 1984 Firm of the Year Award from the American Institute of Architects, California Council, for "excellence in design of distinguished architecture"[40] and reaching for a livelier style beyond the boundaries of conventional modernism.[13]

- He was honored by the Southern California Institute of Architecture in May 1986 for his professional accomplishments and his efforts on behalf of the school's scholarship program.[41]

- Dworsky was awarded a $3.5 million grant by the California Board of Corrections in 1982 to study the idea of the modular jail.[20]

- Dworsky served on the Architectural Evaluation Board for the County of Los Angeles.

- Dworsky also served on the board of directors and the "directors circle" of the Southern California Institute of Architecture.

Walt Disney Concert Hall controversy

In February 1989, the Walt Disney Concert Hall Committee selected Dworsky as executive architect to work with designated architect Frank Gehry in designing the future home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Dworsky was selected to translate Gehry's conceptual designs into working drawings that would meet building code specifications.[42] By 1994, the cost of the project had skyrocketed to $160 million (it eventually reached $274 million), and controversy halted the project. By 1996, a major donor was sought to complete the project by 2001 (four years behind schedule).[43] Gehry and his design came under fire, and some considered him a spoiled, impractical artist.

Gehry publicly blamed Dworsky: "The executive architect was incapable of doing drawings that had this complexity. We helped select that firm. I went to Daniel, supposedly a friend, and I said, 'This is going to fail and we now have the capability to do it, so let us ghost-write it.'" Dworsky refused.[44] Gehry was also quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying: "We had the wrong executive architect doing the drawings. I helped pick him, I'm partly responsible. It brought us to a stop.""[45] Gehry told Los Angeles magazine in 1996 that he "no longer speaks to his former friend (Dworsky)".[46] Gehry continued his public attacks on Dworsky: "He (Dworsky) made a lot of money. He begged me for the job. I'd like to shoot him."[46]

Dworsky was eventually told to stop working on the drawings before he completed them,[46] but he defended himself against Gehry's criticism. "Knowledgeable people were supportive of us. They were saying it's a very complex and unusual design, and they can understand the difficulties in trying to achieve this within a limited budget and a limited schedule. It was unfortunate that Frank came out with his criticism, but he was the center of the storm, having designed the building, and he was just trying to lessen the blame on himself."[45]

Dworsky also told the Los Angeles Times: "This is a one-of-a-kind building. You just don't simply open up the plans and understand them quickly." Dworsky's allies refer to Gehry's work as "confusing".[43] Disney Hall official Frederick M. Nicholas also defended Dworsky's work against Gehry's attacks, denying that there were any problems with the Dworsky drawings not attributable to fast-tracking. Nicholas said: "They were not 'bad' drawings. It was a question of the subs not understanding them."[47]

Notes

- "Architect, Daniel L. Dworsky, FAIA, Receives Lifetime Achievement Award". Business Wire. March 3, 2004.

- Jones, Todd (2007). "Michigan". In MacCambridge, Michael (ed.). ESPN Big Ten College Football Encyclopedia. ESPN Enterprises. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-933060-49-1.

- Tribesmen, Gridiron. "History of Jews in Football". The Encyclopedia Judaica. jewishsports.com. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- "Dworsky, Dan". jewsinsports.org. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- Who's Who In America. I * A–L (62nd ed.). Marquis Who's Who. 2007. p. 1275. ISBN 978-0-8379-7011-0.

- "1947 Football Team". Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan. March 31, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- Florence, Mal (December 27, 1988). "The Magicians: Split Personality in 1947 Helped Michigan Drive Everyone Crazy". Los Angeles Times.

- Green, Jerry (January 2, 2004). "Wistert brothers' fame was built on hard work". The Detroit News.

- "1948 Football Team". Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan. March 31, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- Litke, Jim (December 31, 1997). "Hail to the Victors, 50 Years Later". Associated Press.

- "Dan Dworsky Player Profile and Career Statistics". pro-football-reference.com. 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- "2005 Alumni Awards: Dan Dworsky, FAIA, B.Arch. '50, 2005 taubman college distinguished alumnus". The Regents of the University of Michigan. 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- Whiteson, Leon (May 26, 1988). "L.A. Architecture's Solid Gray Brigade". Los Angeles Times.

- Peinemann, Milo (September 11, 2000). "Merger Sends Architecture Firm to Century City Digs – Cannon Design and Dworsky Associates". Los Angeles Business Journal.

- Kaplan, Sam Hall (February 27, 1985). "Architects Explore the Creative Urge". Los Angeles Times.

- "2005 Alumni Awards: Dan Dworsky, FAIA, B.Arch. '50". Regents of the University of Michigan, Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- "The Michigan Stadium Story: Expansion and Renovation, 1928-1997". Regents of the University of Michigan, Bentley Library. April 27, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- "Drake Stadium – Home Of Bruin Track And Field/Soccer". UCLA. 2007. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- "Report of UCLA Buildings for Fall 2001". UCLA. 2001. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- "California Considers New Jail in Modular Sections". The New York Times. April 15, 1982.

- Litke, Jim (March 8, 1987). "New L.A. Federal Reserve Bank To Open". Los Angeles Times.

- Litke, Jim (April 17, 1988). "C of C Makes Beautification Awards". Los Angeles Times.

- "Southland Firms Capture Most Gold Nugget Awards at PCBC". Los Angeles Times. June 23, 1985.

- "Real Estate Desk". Los Angeles Times. September 15, 1985.

- "Kilroy Opens Airport Center in Long Beach". Los Angeles Times. July 26, 1987.

- "Tishman West leases entire building to New World". Business Wire. August 25, 1987.

- Sussman, Barnett (January 3, 1988). "Office Tower to Open in Orange's the City". Los Angeles Times.

- "Home Savings Building to Be Finished in 1990". Los Angeles Times. July 9, 1989.

- Myers, David W. (June 25, 1989). "New Downtown Apartments Aimed At Affluent". Los Angeles Times.

- Whiteson, Leon (June 4, 1990). "Courting Beauty in Construction: New Van Nuys Municipal Court Combines Functionalism and Dignity of Design". Los Angeles Times.

- "21st Beautification Awards Announced". Los Angeles Times. June 2, 1991.

- Forgery, Benjamin (November 20, 1992). "Design Prizes to 10 Federal Projects". The Washington Post.

- Cusolito, Karen (September 15, 1992). "Reporter enters new era with move to Wilshire Blvd". The Hollywood Reporter.

- "Council Gives 6 Awards for Beautification". Los Angeles Times. May 3, 1992.

- Taylor, Michael (June 22, 1993). "Buck-Passing Follows Breakout at New Jail". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Bustillo, Miguel (March 11, 1996). "Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza Is Experts' Choice, If Not Locals". Los Angeles Times.

- Jarmusch, Ann (April 27, 1997). "Promenade, Children's Park Honored". San Diego Union-Tribune.

- "Designs for Federally Funded Projects Given a Rare Moment in the Architectural Sun". The Washington Post. January 13, 2001.

- Rabin, Jeffrey (March 22, 2000). "Riordan Calls Subway Station Key to Revival of Hollywood Area". Los Angeles Times.

- "Dworsky Cited by State AIA for Excellence". Los Angeles Times. February 17, 1985.

- "SCI-ARC Slates Dinner Dance to Hail Dworsky". Los Angeles Times. May 18, 1986.

- MacMinn, Aleene (February 3, 1989). "Morning Report: Music". Los Angeles Times.

- Holland, Bernard (July 28, 1996). "A Phantom Hall Filled With Discord". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Russell, James S. (November 2003). "Project Diary: The story of how Frank Gehry's design and Lillian Disney's dream were ultimately rescued to create the masterful Walt Disney Concert Hall". Architectural Record.

- Boehm, Mike (September 14, 2003). "A rocky road, step by step; Disney Hall is here, but it wasn't easy". Los Angeles Times.

- D'Arcy, David (August 1, 1996). "Why L.A. hates Frank Gehry". Los Angeles.

- Haithmam, Diane (February 27, 1995). "Disney Hall: Unfinished Symphony?; The Dream of a World Class Music Facility Is Entangled in So Many Financial Problems That Its Future May Be in Jeopardy". Los Angeles Times.

External links

- Photo of Soboleski, Dworsky, Wistert, Elliott and Crisler at 1948 Rose Bowl

- Photo of 1948 Rose Bowl Team - Dworsky 3rd from left in back row