Danish sculpture

Danish sculpture as a nationally recognized art form can be traced back to 1752 when Jacques Saly was commissioned to execute a statue of King Frederick V of Denmark on horseback. While Bertel Thorvaldsen was undoubtedly the country's most prominent contributor, many other players have produced fine work, especially in the areas of Neoclassicism, Realism, and in Historicism, the latter resulting from growing consciousness of a national identity. More recently, Danish sculpture has been inspired by European trends, especially those from Paris, including Surrealism and Modernism.[1]

The beginnings

The earliest traces of sculpture in Denmark date from the 12th century when a stonemason known as Horder was active in the east of Jutland and on the island of Funen decorating churches, especially doors and fonts.[2] From roughly the same period, there are sculpted figures in the granite reliefs depicting the Removal from the Cross in the tympanum above the so-called Cat's Head Door of Ribe Cathedral.[3] In the early 16th century, sculpted altarpieces and pulpits were produced by German artists such as Claus Berg working in Odense Cathedral and Hans Brüggemann who designed the unpainted altarpiece in Schleswig Cathedral. However the Reformation in 1536 brought such decorative work to an almost total stop.[4] During the Renaissance period, sculptors from abroad were the source of work in Denmark. The Flemish sculptor Cornelis Floris from Antwerp produced tombs for Herluf Trolle and Birgitte Gøye (1566–68) in Herlufsholm and for Christian III (1569–79) in Roskilde Cathedral. Gert van Groningen was one of the leading Dutch artists to participate in the design of Kronborg's main entrance. Another Flemish sculptor active towards the end of the 16th century in Denmark was Gert van Egen who designed Frederik II's tomb in Roskilde Cathedral.[5] Similarly, in the 17th century, it was Adriaen de Vries who designed the Neptunus Fountain for Frederiksberg Palace (1615–22) although it was later taken by the Swedes as a prize of war and now stands before Drottningholm Palace.[6]

The development of Danish sculpture was greatly influenced in the mid-18th century by the French sculptor Jacques Saly (1717–1776), who was invited by the Danish government in 1752 to create a statue of King Frederik V.[7] Shortly after the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts was founded in March 1754, Saly was appointed as its director, exerting considerable influence on the workings of the institution. After preparing a number of miniature and full-sized models, Saly finally completed his equestrian statue in 1768 as a bronze casting in the Neoclassical style but it was not unveiled in the courtyard at Amalienborg Palace until August 1771, five years after the king’s death in 1766.[8] It has been called one of the finest equestrian statues in Europe.[7]

Early Neoclassicisism

Johannes Wiedewelt (1731–1802) was one of the primary figures responsible for introducing Neoclassicism to Denmark, inspired by stays in Paris and Rome which were facilitated by travel stipends from the newly established Academy. Soon after his return to Denmark in 1758, he was commissioned to sculpt a memorial monument to the long deceased King Christian VI by his widowed wife, Sophie Magdalene. Completed in 1768, the marble monument was not installed in Roskilde Cathedral until 1777. The sarcophagus with two female figures, "Sorgen" ("Sorrow") and "Berømmelsen" ("Fame") is considered to be Denmark's first Neoclassical work. Wiedewelt went on to design large collections of sculptures for gardens such as those at Fredensborg Palace. In 1769, he completed the monument to King Frederik V in Roskilde Cathedral which includes a large sarcophagus resting on footpieces and decorated by numerous sculptures, behind which is a column topped by an urn, a medallion with the king's portrait, and on each side of the sarcophagus, reaching some nine feet above the floor, are two crowned, grieving female figures representing Denmark and Norway. The memorial chapel was the result of collaboration between Wiedewelt and the architect Caspar Frederik Harsdorff. Wiedewelt was chosen for eight annual periods as Director of the Academy between 1772 and 1794. As a professor there, he introduced his Neoclassical theories to his students including the painter and architect Nikolaj Abraham Abildgaard who later became Director of the Academy and Bertel Thorvaldsen's instructor.[9]

Thorvaldsen

Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844) is the most famous Danish sculptor, recognised across Europe as one of the leading Neoclassical sculptors. After entering the Art Academy in Copenhagen when he was only 11, he went on to win all four of the institution's medals. In 1796, he received a stipend for a relatively short study tour to Italy but, apart from a short visit to Denmark in 1819, he stayed in Rome for over 40 years. After a model for his statue of Jason and the Golden Fleece received recognition from the leading Italian sculptor of the day, Antonio Canova, his success was ensured. Thorvaldsen gradually employed numerous assistants, extending his work to be executed in five studios in Rome, as he received orders from all over Europe.[10]

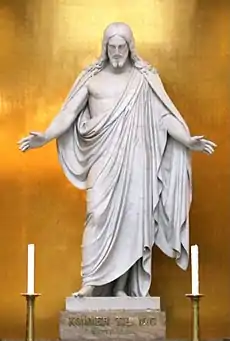

Among his most important works are the colossal series of statues of Christ and the twelve Apostles for the rebuilding of Vor Frue Kirke in Copenhagen. Motifs for his works (reliefs, statues, and busts) were drawn mostly from Greek mythology with statues of Venus, Mercury, Ganymede, Hebe, and Cupid and Psyche, but he also created portraits of important personalities, as in his tomb monument for Pope Pius VII in St Peter's Basilica, Rome or the equestrian statue of Jozef Poniatowski in Warsaw. His works can be seen in many European countries, but there is a very large collection at the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen. During his stay in Rome, Thorvaldsen played an important role in encouraging young Danish artists spending time in the city.[11]

Thorvaldsen's students

Three of those who had studied under Thorvaldsen in Rome made significant contributions to the development of Danish sculpture, influenced on the one hand by their master's interest in classicism and on the other by a growing interest in nationalism in their mother country.

Hermann Ernst Freund (1786–1840), who had been Thorvaldsen's closest assistant in Rome, was an early proponent of Danish romantic nationalism, creating 12 statuettes of figures from Nordic mythology, notably Loki (1822), Odin (bronze 1827) and Thor (1829), all inspired by ancient Greek and Roman mythological works.[12] His masterpiece, the Ragnarok Frieze, which occupied him for many years, was completed by Bissen after his death but was later destroyed by the Christianborg fire. There is a plaster cast of part of the frieze in Statens Museum for Kunst.[13]

Herman Wilhelm Bissen (1798–1868), initially a Neoclassicist, is remembered for the Realism of his monumental works celebrating Danish military victories while reflecting the nationalistic trend of the times. Bissen's Landsoldaten or Danish Soldier (1858) in Fredericia and Isted Lion (1862) in Flensburg were both erected to commemorate the Danish victory over Schleswig-Holstein at the Battle of Isted (Idstedt) on 25 July 1850. The Danish Soldier is notable in that it does not depict a high-ranking officer but rather a simple footsoldier with whom Danish citizens could readily identify.[14] Bissen was inspired to design his massive bronze Isted Lion after studying the Piraeus Lion in Venice where it had been displayed as a prize of war since 1687. After a colourful history of moves to Berlin and Copenhagen, the Isted Lion was finally returned to its original setting in Flensburg in 2011.[15]

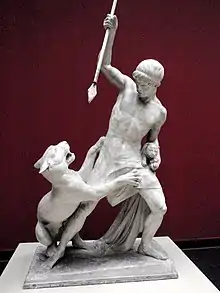

Jens Adolf Jerichau (1816–1883) initially followed closely in Thorvaldsen's footsteps with his Neoclassical work Hercules and Hebe (1846) and his colossal figure of Christ from 1849. He then went on to develop his own, more dynamic style which can be seen in The Panther Hunter (1846), a work which has been seen as a prime example of the relationship between classical art and modern trends in naturalism.[16]

_by_H._E._Freund.jpg.webp) Hermann Ernst Freund: Thor (1829)

Hermann Ernst Freund: Thor (1829) Herman Wilhelm Bissen: Landsoldaten (1858)

Herman Wilhelm Bissen: Landsoldaten (1858) Herman Wilhelm Bissen: Isted Lion (1862), now in Flensburg

Herman Wilhelm Bissen: Isted Lion (1862), now in Flensburg Jens Adolf Jerichau: The Panther Hunter (1846)

Jens Adolf Jerichau: The Panther Hunter (1846)

Late 19th century

Some sculptors continued to create statues based on classical figures but now with a more Naturalistic look. A good example is Aksel Hansen's Echo (1888) in the Rosenborg Castle Gardens. The Greek nymph's lively contemporary look of a woman in motion contrasts with the more rigid harmony of Classicism.[17] Anders Bundgaard (1864–1937) is remembered for his huge statue near Langelinie of the Norse goddess Gefion (1900) driving her oxen.[18]

But as the turn of the century approached, new trends developed, starting with Historicism and the need to pay tribute to Danes who had become famous. August Saabye (1823–1916), one of Bissen's students at the Academy, first maintained the Neoclassical tradition but was later inspired by French Naturalism.[19] His finest work is certainly the bronze statue of Hans Christian Andersen in the Rosenborg Gardens which he completed in 1880. By depicting Andersen in a sitting position addressing his audience, Saabye was able to capture the author's inner qualities which meant so much to the Danish public.[20] Bissen's son, Vilhelm Bissen, also sculpted a number of famous figures including N. F. S. Grundtvig at the Marble Church, Christian IV at Nyboder and Absalon on Højbro Plads in Copenhagen.[21]

The other evolving artistic trend which attracted the attention of Danish sculptors was Symbolism. Niels Hansen Jacobsen (1861–1941), who spent several years in Paris at the end of the century, came under the influence of Auguste Rodin. He created several controversial bronzes including Trold, der vejrer kristenblod (1896) or Troll that smells Christian blood based on a Norse folktale. The original is in Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek but there is a copy outside Jesus Church in Valby for which it was originally designed.[22] Other Danish sculptors who were influenced by Rodin's symbolism include Stephan Sinding (1846–1922) and Rudolph Tegner (1873–1950).[23]

Aksel Hansen: Echo (1888)

Aksel Hansen: Echo (1888) Vilhelm Bissen: Absalon (1902)

Vilhelm Bissen: Absalon (1902) Vilhelm Bissen: Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1894)

Vilhelm Bissen: Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1894) August Saabye: Hans Christian Andersen (1880)

August Saabye: Hans Christian Andersen (1880)

Anders Bundgaard: Gefion (1900)

Anders Bundgaard: Gefion (1900) Niels Hansen Jacobsen: Døden og moderen (1892)

Niels Hansen Jacobsen: Døden og moderen (1892) Stephan Sinding: Valkyrie (1908)

Stephan Sinding: Valkyrie (1908) Niels Hansen Jacobsen: Trold, der vejrer kristenblod (1896)

Niels Hansen Jacobsen: Trold, der vejrer kristenblod (1896)

Early 20th century

One of the first women to become active in Danish sculpture was Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen (1863–1945), the wife of Carl Nielsen. A sense of vitality combining Naturalism with Classicism can be seen her works, most of which depict either animals or the human figure. Of particular note are the three bronze doors of Ribe Cathedral (1904), the equestrian statue of King Christian IX (1927) and the monument dedicated to her husband, The Young Man playing Pan-pipes on a Wingless Pegasus (1939), in Copenhagen.[24]

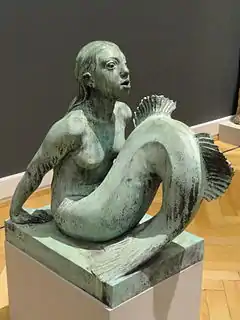

Kai Nielsen (1882–1924) accomplished a significant breakthrough with his erotic female figures, frequently based on mythological characters. Among his finest works are the bronze Blind almuepige (Blind Peasant Girl, 1907), Marmorpigen (The Marble Girl, 1910) and Leda med svanen (Leda and the Swan, 1918) in limestone. At the Academy, he had been instructed by Edvard Eriksen (1876–1959) who is famous for another bronze female figure, Den lille havfrue (The Little Mermaid, 1913).[25]

For a period, Denmark became identified with French-inspired Modernism with sculptors such as Jean Gauguin (1881–1961)and Adam Fischer (1888–1968) demonstrating a spirit of cultural optimism in contrast to the nations in conflict during the First World War. Fischer's geometrically designed Danserinde (Dancing Girl) from 1917 also demonstrates the influence of Cubism. Another significant contributor of the period was Svend Rathsack (1885–1941) who together with the architect Ivar Bentsen designed the Maritime Monument (Søfartsmonumentet) on Langelinie.[26]

Edvard Eriksen: The Little Mermaid (1913)

Edvard Eriksen: The Little Mermaid (1913)

The above file's purpose is being discussed and/or is being considered for deletion. See files for discussion to help reach a consensus on what to do. Kai Nielsen: Vandmoderen (1920)

Kai Nielsen: Vandmoderen (1920) Kai Nielsen: Venus med æblet (1909)

Kai Nielsen: Venus med æblet (1909) Kai Nielsen: Granite statue, Blågårds Plads, Copenhagen (1916)

Kai Nielsen: Granite statue, Blågårds Plads, Copenhagen (1916) Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen: Mermaid (1921)

Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen: Mermaid (1921) Svend Rathsack: Søfartsmonumentet (1928)

Svend Rathsack: Søfartsmonumentet (1928)

Interwar period

Between the wars there was an interest in creating statues of ordinary people in their everyday clothes as can be seen in Povl Søndergaard's Mand og pige (Man and Girl, 1934)[27] and Knud Nellemose's Avismanden Leitriz (1935), depicting a newspaperman dressed in the clothes he wore when selling newspapers in the streets of Copenhagen.[28] Gunnar Westman (1915–1985) who came under the influence of Bror Hjorth in Sweden developed a simplified style which can be seen in his works representing children such as Børn ved vinduet (Children at the Window, 1947), Gøgeungen and Børnehaven (1948).[29] Also in the 1930s, Gottfred Eickhoff (1902–1982) sculpted simplified human figures inspired by the influence of his French instructors Charles Despiau and Aristide Maillol. Unveiled in 1940, his statue of Roepiger (The Beet Girls) can be seen in Sakskøbing on the island of Lolland.[30]

The 1930s also saw the influence of Surrealism, for example in the work of Ejler Bille (1910–2004) with his early animal-like figures.[31] Henry Heerup (1907–1993) developed an interest in "junk models" made from trash he found in the streets. He is also remembered for sculpting the original shape of a stone.[32] Sonja Ferlov, remembered for her Owl (1935) and her African-inspired designs, was also an important associate of these surrealistic artists who together were leading members of the Linien association.[33][34] Probably the best known participant in Danish Surrealism was Wilhelm Freddie (1909–1995) who took a more explicitly sexual approach to Surrealism. This can be seen in his Sex-paralysappeal (1936) which was confiscated by the police on the grounds of pornography.[35][36]

Post-war developments

As in France, immediately after the Second World War Danish sculpture was dominated by Spontaneism and Concretism. Spontaneism, which stemmed from Expressionism and Surrealism, led to the formation of the COBRA movement with Asger Jorn (1914–1973) in the forefront.[37] His most important sculptural work, the large relief (1959) for Århus Statsgymnasium, is a huge ceramic, 27 metres long.[38][39] Concretism which developed from the abstract geometrical art of the 1920s was influenced by the Dada movement leading to Linien II in 1947. Also in the 1950s, Svend Wiig Hansen (1922–1997) focused on the erotic power of the human body as in his cement Moder Jord (Mother Earth, 1953) in Herning Art Museum.[40][41] An important and profuse contributor in the 1950s and 1960s was Jørgen Haugen Sørensen (born 1934) whose slaughtered animals allowed him to explore new avenues of abstract Expressionism, representing his views of the human condition in his own, often brutal style.[42][43]

The Concretist movement sought to achieve a purity of expression for all cultures and ages. Robert Jacobsen (1912–1993), one of its early proponents, gained international recognition with his welded iron sculptures where lines and surfaces were enclosed in autonomous universes.[37][44] Another concretist in Linien II was Gunnar Aagaard Andersen (1919–1982) who developed socially-oriented sculpture at an international level.[45]

In the 1960s, minimalistic tendencies in German and American art were behind the meta-objective approach of Willy Ørskov (1920-1990) who used everyday materials such as plastics and often inflated rubber to produce his works. Examples include Sommerskulptur (1965, Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum) and Stabiler-Instabiler-Labiler (1968).[46][47] Others who experimented with untraditional materials were Bjørn Nørgaard (born 1947), Hein Heinsen (born 1935) and Per Kirkeby (born 1938).[37]

The 1970s showed a growing interest in American-inspired installations depicting the surrounding world and leading in 1973 to the Institut for Skalakunst (Institute for Scalable Art) which was behind numerous democratically designed decorative works in public spaces around the country. The principal proponents were Mogens Møller, Hein Heinsen and Stig Brøgger.[48][49]

In the 1980s, international Post-Modernism heralded a return to a more classical, intellectually based approach to sculpture avoiding the excesses of the avant-garde. Players here included Henrik B. Andersen, Morten Stræde, Øivind Nygaard, Søren Jensen and Elisabeth Toubro who had all been influenced at the Art Academy by Willy Ørskov and Hein Heinsen.[37][48]

Current trends

Today, young Danish artists are increasingly seeking inspiration abroad, especially at Berlin's exhibitions. Per Arnoldi, Per Kirkeby and Olafur Eliasson have all carried out large-scale decorative work in the new Copenhagen Opera House (2004)[50] while in 2003 Elisabeth Toubro completed her controversial Vanddragen (Water Dragon, 2003) in the centre of Aarhus.[51] The recent Ørestad development has also seen the completion of monumental works including Per Kirkeby's Murstensskulptur (The Brick Wall, 2004), Hein Heinsen's bronze Den store udveksler (The Great Exchange, 2005) and Bjørn Nørgaard's colourful Kærlighedsøen (Lake of Love, 2010).[48][52]

Museums and sculpture parks

In addition to works displayed in towns and cities, a number of museums and gardens have collections of Danish sculpture:

- ARoS, the Aarhus Kunstmuseum[53]

- Heart, the Herning Museum of Contemporary Art[54]

- J.F. Willumsens Museum in Frederikssund

- Kunsten, Aalborg[55]

- Gallery Galschiøt, Odense

- Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, 35 km north of Copenhagen

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

- Rosenborg Castle Gardens, Copenhagen

- Rudolph Tegner Museum near Dronningmølle, 50 km north of Copenhagen

- Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

- Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Denmark |

|---|

References

- "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996. (in Danish) ISBN 87-00-24612-3.

- "Horder", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Darwin Porter, Danforth Prince, "Ribe Domkirke", Frommers Denmark, John Wiley & Sons, 2009, p.322. ISBN 978-0-470-43212-9.

- "Danmark - billedkunst (Romansk og gotisk kunst)", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "Danmark - billedkunst (Renæssancen)", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "Danmark - billedkunst (Barokken)", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Nelson, Nina (1973). Denmark. Batsford. p. 42.

- Bent Sørensen, "Saly, Jacques François Joseph", Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- Hakon Lund, "Wiedewelt, Johannes", Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "About Bertel Thorvaldsen" Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine, Thorvaldsen Museum. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Bertel Thorvaldsen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "H.E. Freund", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Jens Peter Munk, "Hermann Ernst Freund". Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- "Dansk skulptur i nationalistisk perspektiv" Archived 2012-07-28 at Archive.today, Skulpturstudier: dansk skulptur 1800-1940. (in Danish) Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Inge Adriansen, "Istedløven genopstår som vennegave", Videnskab dk. (in Danish) Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- "Antikken længe leve: 1800-tallet" Archived 2011-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, Skulpturstudier: dansk skulptur 1800-1940. (in Danish) Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- "Antikken længe leve: Omkring år 1900" Archived 2012-07-18 at Archive.today, Skulpturstudier: dansk skulptur 1800-1940. (in Danish) Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- "Gefion Fountain - Copenhagen", Visit Denmark. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "August Saabye", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- Flemming Friborg, "Fra Myte til Psyke" in "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996, p. 32. (in Danish) ISBN 87-00-24612-3.

- "Vilhelm Bissen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Niels Hansen Jacobsen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 12 January 2012

- Flemming Friborg, "Fra Myte til Psyke" in "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996, p. 312

- "Anne Marie Carl Nielsen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- "Kai Nielsen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- Hanne Abildgaard, "Modernitet og Menneske" in "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996, p. 116 et seq.

- "Povl Søndergaard", Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Knud Nellemose (1908-97): Avismanden Leitriz, 1935. Kunststen", Vejle Kunstmuseum. (in Danish) Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Gunnar Westman". Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Gottfred Eickhoff", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "Ejler Bille" Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Galleri Profilen. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "Heerup", Lauritz.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Sonja Ferlov Mancoba : 1911-1985", CoBrA. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Sonja Ferlov Mancoba: 100 years", Museum Jorn. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Wilhelm Freddie", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Wilhelm Freddie", Kunsten. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Mikkel Borg, "Skulpturen, tiden og verden 1945–1995" in "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996, p. 193 et seq. (in Danish).

- "Museum Jorn". Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Asger Jorn på Århus Statsgymnasium" Archived 2006-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, Århus Statsgymnasium. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Svend Wiig Hansen", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Sculptur" Archived 2008-04-06 at the Wayback Machine, Herning Kunstmuseum. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Jørgen Haugen Sørensen at Statens Museum for Kunst", Art Knowledge News. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Pia Kristine Münster, "Jørgen Haugen Sørensen", Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Billedmageren Robert Jacobsen", Kunsten. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Anne Duer, "Gunnar Aagaard Andersen: a ground-breaking hybrid artist", Statens Museum for Kunst. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Willy Ørskov", Kunsten. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Willy Ørskov", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Billedkunst - Efter 1945", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Houses of Knowledge", University of Copenhagen, p.185 and p.195. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Copenhagen - Denmark's Cultural Capital", Visit Denmark. Retrieved 29 January 2012

- "Torvenes Brøndsløjfe/Vanddragen", Kend Aarhus. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Kunstværker giver byen identitet", Ørestad, 17 August 2010. (in Danish) Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "The Collection", ARoS. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "The Collection" Archived 2012-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Heart. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Collection" Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, Kunsten. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

Literature

- Abildgaard, Hanne; Bogh, Mikkel; Friborg, Flemming: "Dansk Skulptur i 125 år", Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1996, 327 pp. (in Danish) ISBN 87-00-24612-3.

External links

![]() Media related to Sculptures in Denmark at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sculptures in Denmark at Wikimedia Commons