David McMillan (smuggler)

David McMillan (born 1956) is a British-Australian drug smuggler who is best known for being the only Westerner on record as having successfully escaped Bangkok's Klong Prem prison.[1] His exploits were the subject of the 2011 Australian telemovie Underbelly Files: The Man Who Got Away.

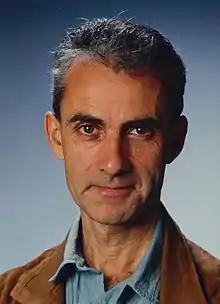

David McMillan | |

|---|---|

David McMillan 2004 | |

| Born | 9 April 1956 London, England, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Photographer, TV presenter, drug smuggler, writer |

Early life

McMillan was born in Saint Marylebone, London, England, on 9 April 1956. He is the son of John McMillan CBE, who was the controller of Associated-Rediffusion Television, and his Australian wife. After his parents separated, he emigrated to Australia with his mother and sister.[2] He attended Caulfield Grammar School in Melbourne, Victoria. As a child, 12-year-old McMillan appeared nightly on the Nine Network's 'Peters Junior News', presenting news stories for children in a regular 5-minute TV bulletin. After working as a cinema projectionist and camera operator in Sydney, he began a short-lived career in advertising with Masius Wynne Williams in Melbourne.

Criminal career

A part-time job at a city cinema introduced McMillan to the fringes of the underworld; a group of safe-crackers who had turned to narcotics when police surveillance curtailed their traditional profession. Connections with the free-marijuana hippie lobbyists brought those two worlds together and a tempting opportunity for McMillan, who was well-travelled. At the time, he was a distributor of the monthly magazine, The Australasian Weed, a drug-reform periodical, and advocated the complete lifting of the prohibition against drugs for recreational use. McMillan then began a career as a drug smuggler, during which he developed the bag-duplication system at Sydney's Kingsford-Smith Airport in the late 1970s as he smuggled hashish from India. In 1979, McMillan fell out with disgraced peer Lord Tony Moynihan after the exiled lord attempted to trap McMillan in a gambling-sting operation using the large-scale bets of the Chinese-run cockfights in Manila. Moynihan had hoped to employ McMillan's technical expertise to detonate an explosive capsule in the necks of fighting cocks, and so determine the winners.

Moynihan planned only to swindle McMillan out of the betting stake after a test game. McMillan was alerted to the scam by his Chinese film-making friends and left the Philippines after cautioning Moynihan. Lord Moynihan would later move on to hoodwink smuggler Howard Marks in the 1980s, resulting in Marks's conviction and imprisonment in America. Imprudent spending attracted the attention of federal police when a Clénet Coachworks car was imported from California bearing papers that had greatly undervalued the vehicle. This slip-up led to a major investigation which eventually revealed houses, businesses and properties along the eastern coast of Australia bought with cash and valued in millions of dollars. These assets later became the subject of Australia's first important confiscation of drug-earned assets. At the peak of his career in the 1980s, McMillan was a multi-millionaire and maintained homes, offices and apartments all over the world.[3]

After three years, McMillan and business partner Michael Sullivan were arrested following Operation Aries, a Victoria Police/Federal Police taskforce operation reported to have cost over A$2 million. McMillan and Sullivan, along with their partners, Clelia Teresa Vigano and Mary Escolar Castillo respectively, had been arrested on 5 January 1982 for conspiracy to import heroin. The four had several false passports between them and stood trial with S. Chowdury and Brendan Healy on twelve counts of conspiring to import drugs between 1979 and 1981. Healy was acquitted on all charges, and nine others accused of the conspiracy accepted indemnity against prosecution in exchange for testifying against their co-conspirators. McMillan stood accused of travelling under 30 false passports and keeping station houses in London, Brussels and Bangkok. The trial heard charges of an attempt to escape Melbourne's high-security Pentridge Prison by helicopter using former SAS personnel in a scheme engineered by a vengeful Lord Moynihan.[4]

The prosecution opposed bail for Castillo, who had a four-month-old baby with Sullivan, because she had access to funds and it was thought she could flee to her wealthy parents in her native Colombia. The police surgeon reported that all four defendants were habitual heroin users.[5] Clelia Vigano and Mary Castillo were two of three women who died in a fire at HM Prison Fairlea on the evening of Saturday 6 February 1982.[6] After her death, Castillo's baby went into the custody of Sullivan's mother.[7] The consequent six-month trial produced 116 witnesses and a hung jury that finally returned a verdict after seven days sequestration. Despite being acquitted of 11 of the 12 counts, McMillan was found guilty of the remaining count and was sentenced to 17 years, before being released in 1993 on parole.[8] During the trial, agents from the United States’ Drug Enforcement Administration testified against the Thai national Chowdury who they believed had links to the Golden Triangle's third biggest heroin exporter, and to the kidnap and murder of an agent's wife in Chiang Mai. McMillan denied any connection with Chowdury, and was acquitted of the relevant charge, however the American involvement led to a lifelong antipathy between the DEA and McMillan.[19].[9]

McMillan was arrested in April 2012, in an operation referred to Bromley police by the UK Border Agency concerning an ounce of heroin mailed from Pakistan. In the consequent trial, an undercover policewoman testified to delivering a package from which thirty grams of Asian heroin had been removed. McMillan had not opened the parcel, addressed to a previous resident, and denied any knowledge of the unidentified sender.[20].[10]

After a six-day trial McMillan was sentenced at the Croydon Crown Court to six years’ imprisonment for the evasion of the prohibition on importing A-class drugs. The verdict is subject to appeal as at 2014.

Thailand

While on parole, McMillan flew to Thailand, travelling under the name Daniel Westlake. After a close-call at Don Muang airport, he was arrested in Bangkok's Chinatown and charged with heroin trafficking. He was held in Klong Prem Central Prison.[11] Klong Prem Central prison (Thai: คลองเปรม; rtgs: Khlong Prem) is a maximum security prison in Chatuchak District, Bangkok, Thailand. The prison has several separate sections and houses up to 20,000 inmates. For two years, McMillan watched as inmates fell prey to drugs, disease, violence, death and despair. Due to his financial status, McMillan lived more comfortably than the average inmate while in prison.[12] McMillan had his own chef and servants, dined on food bought from the supermarket, and also had his own office, television and radio.[12]

Facing the death penalty and a transfer to Asia's most notorious prison Bang Kwang Central Prison, also known colloquially as the Bangkok Hilton, McMillan resolved that this was not going to be the end of him. McMillan later stated, "I had no interest in my trial. I knew what it was going to be like – a farce, a mockery, a sham and a travesty – and that I would receive the death penalty." McMillan escaped from Klong Prem in August 1996, never to be seen in Thailand again.[13] During the night he cut the cell bars with hacksaws, scaled seven inner walls, then mounted the outer wall using a bamboo-pole ladder. Once out of the prison, McMillan changed into civilian clothes and carried an umbrella as he walked away from the prison. McMillan credits the umbrella with helping him escape, saying that "escaping prisoners don't carry umbrellas".

Four hours later, with a false passport, he was on a flight to Singapore and 12 hours later was sitting in a hotel.[11] Prison authorities raced to the airport to look for him once they realised he was missing. However, McMillan caught a plane in time and later said, "There’s nothing better than the suction sound of an aeroplane door being sealed."[14] Future Australian attorney-general Robert McClelland when praising Australia's embassy in Thailand remarked that McMillan: "… a prisoner... escaped from the Thai jail in quite exceptional and athletic circumstances. In terms of mere escape, it was really quite an achievement."[15] An account of the Thai prison and his jail break can be found in his 2008 autobiography Escape.[16]

Pakistan

After fleeing Thailand using false documents, McMillan was kept safe in Balouchistan, Pakistan under the protection of Mir Noor Jehan Magsi of the Magsi clan, from where he began operations to Scandinavia.[17]

McMillan was arrested in Lahore, Pakistan, as a result of the confession of a captured courier. McMillan was flown to Karachi, Pakistan, and held in Karachi Central Jail. This jail maintained a class system for prisoners, through which McMillan kept servants and private rooms. Due to a financial dispute with the prison superintendent concerning his illegal mobile phone, McMillan was transferred at night to the Hyderabad jail, where he was kept in the dungeons until being rescued by Lord Magsi.[18] Not wishing to add to the existing Interpol warrants, McMillan returned to Karachi to stand trial, where he was acquitted by a Customs Court judge who found there was no evidence that McMillan had sponsored the courier, and that the government of Thailand had not made representations for extradition.

The courier, a former boxer from Liverpool, was sentenced to five years in custody, eventually released and has since disappeared. During his time in Hyderabad, McMillan formed a friendship with the members of a Moscow street gang, who were completing a ten-year sentence for the hijack of a commercial liner outside their Russian prison. The gang had been separated by the Russian prison authorities, a decision overcome by gang leader Andreas, who flew his hijacked aircraft to Krasnoyarsk from where he freed the other members of his team before flying to Pakistan, then under the control of General Zia al Huq, known for his independence from both the Soviet Union and the US. The story of the Russian prisoners and their ordeal is outlined by McMillan in Unforgiving Destiny, although the author withdrew the commissioned book, "White Russians", as "too violent — even for me — and depressing".[19]

Return to England

McMillan returned to London in 1999. He was arrested in 2000 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He was arrested at Heathrow airport in 2002 for smuggling 500 grams of class A drugs. For this crime he served a sentence of two years. As of 2007, the warrant for McMillan's arrest in Thailand for heroin trafficking is still active and he is still wanted in Australia for breaching parole. However, the UK government does not extradite anyone to a country which carries out the death penalty, and breaching parole is not an extraditable offence.[20] In June 2009, McMillan appeared as a guest in a 50-minute episode of Danny Dyer's Deadliest Men 2: Living Dangerously, which aired on Bravo TV.

The episode includes interviews and presents McMillan as having settled peacefully with his partner Jeanette and children.[21] An Australian television company Screentime, released a telemovie that aired on Channel Nine in February 2011, loosely based on McMillan's smuggling, arrest, imprisonment in Bangkok and briefly outlined his escape from Klong Prem. The low-budget film was the 3rd in the Underbelly Files series. McMillan is to see published McVillain: the Man Who Got Away, scheduled for launch 1 April 2011.[22] McVillain is the first in a series planned for the great rises and falls in McMillan's life. Although launched on the springboard of the Underbelly telemovie, the books differ in almost every factual event according to McMillan.

In November, 2014, Thailand formally began extradition proceedings against McMillan in London. He was arrested at the request of the Thai government, and held at Wandsworth prison. A long-running challenge began at the Westminster Magistrates Court headed by defence barrister Tim Owen, QC.[23] Evidence was presented detailing human-rights abuses under the rule of the Thai generals who had staged a coup in May of that year, as well as expert evidence on Thai prison conditions. However, Judge Arbuthnot ruled against McMillan, as did the UK Home Secretary. However, two weeks before McMillan was due to be sent back to Bangkok, the Thai authorities withdrew their request, stating technical reasons. McMillan was freed in September, 2016.

In late April, 2017, McMillan published an autobiography of the 35-year pursuit by authorities that resulted in capture and escapes throughout the world, focusing on the persistence of one DEA agent. Unforgiving Destiny – The Relentless Pursuit of a Black Marketeer (ISBN 978-1544253053) is dominated by the years in Baluchistan and Afghanistan, his dealings with Taliban as a friend is kidnapped, and his role as advisor to a tribal warlord. A contrast is made between the central Asian badlands and the high life when at the peak of McMillan's smuggling success throughout Colombia, New York and Scandinavia. Of the latest book, McMillan says: “The challenge is to present the facts, real life, as part of readers’ own lives when, for me, the events were often felt as unrelenting terror. I suppose the fact I was up against implacable forces helped me – not in survival, of course, but in telling the story.”[24] He says the lengthy book is, “an attempt to fill in the important blanks, perhaps my last.” A link to the music of the period is online.[25] Recordings of the author narrating selections of the book are available.[26] Of this latest release, McMillan says, "I have tried to craft the action to higher standards, but with biography, there's no dodging the revealing of motives. The trick is to do it in a line. After all, as Sam Spade says: "The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter."[27] For one month, until December, the eBook edition of the book is available without cost from the author's website. "I won’t make a dime," McMillan announced, "but it’s the story that matters."[26]

References

- ISBN 9810575688

- "Life and Crimes with Andrew Rule: The charmed and charming life of McVillain on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts (in Japanese). Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- Drummond, Andrew (8 September 2007). "Drug runner a dead man laughing". The Australian.

- Sydney Morning Herald. Copter Plan Foiled. 21 January 1983

- Heroin syndicate used 17 false passports: police. The Age: 7 January 1982, p.5.

- Bolt, Andrew. State warned in 1978 of Fairlea fire hazard. The Age: 8 February 1982, p.1.

- Grandmother to care for fire victim's son. The Age: 11 February 1982, p.17.

- an article in the Australian Financial Review gives his view of day-release after a long sentence

- Mills, James, The Underground Empire, 1978

- Trial Transcript, Croydon Crown Court, 5 August 2012

- Andrew Drummond in Bangkok and Paul Cheston in London (14 September 2007). "Drug dealer who escaped Bangkok jail is on the run in London". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2007/09/16/lifestyle/lifestyle_30048997.php

- "How to plan a successful jailbreak". BBC News. 1 March 2009.

- http://www.metro.co.uk/news/862906-david-mcmillan-how-i-made-my-jailbreak-from-klong-prem-prison#ixzz1gVCpeYCd

- Andrew Rule (12 September 2009). "There Was A Crooked Man". Melbourne: The Age. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- http://www.thaiprisonlife.com/books/escape/

- Andrew Rule (2000). The One Who Got Away. The Sunday Age, Melbourne.29 October 2000

- Whinnett, Ellen (7 January 2017). "Free for the first time: How this Aussie drug smuggler dodged death". The Advertiser.

- "Unforgiving Destiny", Amazon-Createspace books, 2017, p. 397

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.panmacmillan.com.au/display_title.asp?ISBN=9780980717044&Author=McMillan,%20David

- Westminster Magistrates Court record May, 2016

- http://davidmcmillan.net/

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL15mJziZMVmuKG4CY7yCpyaaxRPjII33I

- http://unforgivingdestiny.com/

- https://plus.google.com/109711901472375825401/posts/EmhK7bnbMHh

External links

- Official website, with background to Unforgiving Destiny, photo gallery and interviews

- ESCAPE Paperback: 320 pages, Publisher: Mainstream Publishing (3 July 2008) Language English ISBN 978-1-84596-345-3

- ESCAPE: THE PAST Paperback: 264 pages, Publisher: Monsoon Books (Oct 2011) Language English; ISBN 9789814358279 paperback Amazon listing; ISBN 9789814358286 ebook

- Escape from Klong Prem Richard Barrow, ThaiPrisonLife.com

- Unforgiving destiny: Amazon UK author and title pages Published 2017; 422 pages, 6"x9" Trade format