Degenerate music

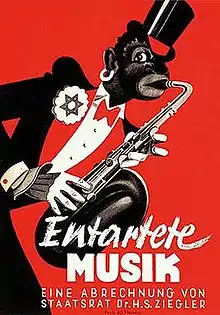

Degenerate music (German: Entartete Musik, German pronunciation: [ɛntˈaʁtɛtə muˈziːk]) was a label applied in the 1930s by the Nazi government in Germany to certain forms of music that it considered harmful or decadent. The Nazi government's concerns about degenerate music were a part of its larger and better-known campaign against degenerate art (German: Entartete Kunst). In both cases, the government attempted to isolate, discredit, discourage, or ban the works.

Racial emphasis

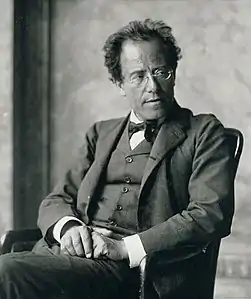

Jewish composers such as Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Mahler were disparaged and condemned by the Nazis (Petit and Giner 2015, 34). In Leipzig, a bronze statue of Mendelssohn was removed. The regime commissioned music to replace his incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream (Petit and Giner 2015, 42).

Though the Nazis wanted to discredit Jewish artists because of their race, they also wanted to have a better reason. The excuse was that some music was “anti-German” and that was why some songs needed to be banned. The certainty of this philosophy was contrasted by the inability to say what counted as “anti-German”. Many people, like Goebbels, could not point to what was German music and what had a “Jewish influence”. Goebbels, who was not a musician nor had any expertise in the subject, said “all music was not suited for everyone" (Potter n.d.)

The Nazis also regulated jazz, including the banning of solos and drum breaks, scat, "Negroid excesses in tempo" and "Jewishly gloomy lyrics" (Gould 2012).

Discrimination

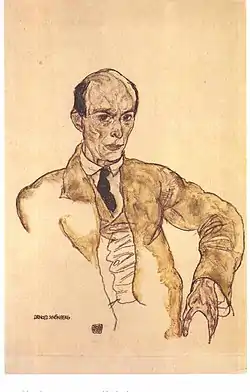

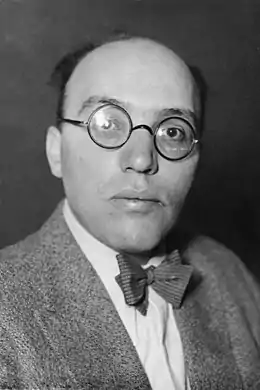

From the Nazi seizure of power onward, these composers found it increasingly difficult, and often impossible, to get work or have their music performed. Many went into exile (e.g., Arnold Schoenberg, Kurt Weill, Paul Hindemith, Berthold Goldschmidt); or retreated into "internal exile" (e.g., Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Boris Blacher); or ended up in the concentration camps (e.g., Viktor Ullmann, or Erwin Schulhoff).

Like degenerate art, examples of degenerate music were displayed in public exhibits in Germany beginning in 1938. One of the first of these was organized in Düsseldorf by Hans Severus Ziegler, at the time superintendent of the Weimar National Theatre, who explained in an opening speech that the decay of music was "due to the influence of Judaism and capitalism".

Ziegler's exhibit was organized into seven sections, devoted to (Anon. 1938, 629):

- The influence of Judaism

- Arnold Schoenberg

- Kurt Weill and Ernst Krenek

- Minor Bolsheviks (Franz Schreker, Alban Berg, Ernst Toch, etc.)

- Leo Kestenberg, director of musical education before 1933

- Hindemith's operas and oratorios

- Igor Stravinsky

From the mid-1990s the Decca Record Company released a series of recordings under the title "Entartete Musik: Music Suppressed by the Third Reich", covering lesser-known works by several of the above-named composers.

See also

References

Bibliography

- Anon. 1938. "Musical Notes from Abroad". Musical Times 79, no. 1146 (August): 629–30.

- Gould, J. J. 2012. "Josef Skvorecky on the Nazis' Control-Freak Hatred of Jazz The Atlantic (3 January; accessed 29 September 2019)

- Petit, Elise, and Bruno Giner. 2015. Entartete Musik. Musiques interdites sous le IIIe Reich. Paris: Bleu Nuit éditeurs.

- Potter, Pamela (n.d.). "Defining "Degenerate Music" in Nazi Germany". Orel Foundation. The Orel Foundation. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

=urther reading

- Dümling, Albrecht. 2002. "The Target of Racial Purity: The 'Degenerate Music' Exhibition in Düsseldorf, 1938". In Art, Culture, and Media Under the Third Reich, edited by Richard A. Etlin, 43–72. Chicago Series in Law and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22086-4.

- Haas, Michael. 2013. Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15430-6 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-300-15431-3 (pbk).

- Levi, Erik. 1994. Music in the Third Reich. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-10381-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-312-12948-4 (pbk).

- Potter, Pamela M. 2006. "Music in the Third Reich: The Complex Task of 'Germanization'". In The Arts in Nazi Germany: Continuity, Conformity, Change, edited by Jonathan Huener and Francis R. Nicosia, 85–110. New York and Oxford: Berghan Books. ISBN 1845452097.