Dei verbum

Dei verbum, the Second Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, was promulgated by Pope Paul VI on 18 November 1965, following approval by the assembled bishops by a vote of 2,344 to 6. It is one of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council, indeed their very foundation in the view of one of the leading Council Fathers, Bishop Christopher Butler. The phrase "Dei verbum" is Latin for "Word of God" and is taken from the first line of the document,[2] as is customary for titles of major Catholic documents.

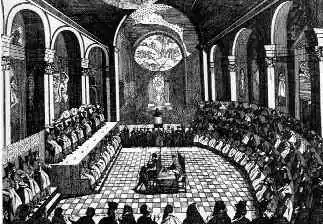

| Second Vatican Ecumenical Council Concilium Oecumenicum Vaticanum Secundum (Latin) | |

|---|---|

Saint Peter's Basilica Venue of the Second Vatican Council | |

| Date | 11 October 1962 – 8 December 1965 |

| Accepted by | Catholic Church |

Previous council | First Vatican Council |

| Convoked by | Pope John XXIII |

| President | Pope John XXIII Pope Paul VI |

| Attendance | up to 2,625[1] |

| Topics | The Church in itself, its sole salvific role as the one, true and complete Christian faith, also in relation to ecumenism among other religions, in relation to the modern world, renewal of consecrated life, liturgical disciplines, etc. |

Documents and statements | Four Constitutions:

Three Declarations:

Nine Decrees:

|

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Antiquity (c. 50 – 451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Modernity (1545–1965) |

|

|

Contents of Dei verbum

The numbers given correspond to the chapter numbers and, those in parentheses, to the section numbers within the text.

- Preface (1)

- Revelation Itself (2–6)

- Handing On Divine Revelation (7–10)

- Sacred Scripture, Its Inspiration and Divine Interpretation (11–13)

- The Old Testament (14–16)

- The New Testament (17–20)

- Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church (21–26)

The full text in English is available through the Holy See's website from which the excerpts below have been taken. The footnotes have been inserted into the text at the appropriate places in small print and indented for the convenience of the present reader.

Another widely used translation is Austin Flannery OP (ed.), "Vatican Council II" (2 volumes).

Concerning sacred Tradition and sacred Scripture

In Chapter II under the heading "Handing On Divine Revelation" the Constitution states among other points:

Hence there exists a close connection and communication between sacred Tradition and sacred Scripture. For both of them, flowing from the same divine wellspring, in a certain way merge into a unity and tend toward the same end. For Sacred Scripture is the word of God inasmuch as it is consigned to writing under the inspiration of the divine Spirit, while sacred tradition takes the word of God entrusted by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit to the Apostles, and hands it on to their successors in its full purity, so that led by the light of the Spirit of truth, they may in proclaiming it preserve this word of God faithfully, explain it, and make it more widely known. Consequently it is not from Sacred Scripture alone that the Church draws her certainty about everything which has been revealed. Therefore both sacred tradition and Sacred Scripture are to be accepted and venerated with the same sense of loyalty and reverence.[3]

The Word of God is transmitted both through the canonical texts of Sacred Scripture, and through Sacred Tradition, which includes various forms such as liturgy, prayers, and the teachings of the Apostles and their successors. The Church looks to Tradition as a protection against errors that could arise from private interpretation.[4]

Concerning the inspiration and interpretation of sacred Scripture

The teaching of the Magisterium on the interpretation of Scripture was summarized in DV 12, expressly devoted to biblical interpretation. Dei Verbum distinguished between two levels of meaning, the literal sense intended by the biblical writers and the further understanding that may be attained due to context within the whole of Scripture.[5]

In Chapter III under the heading "Sacred Scripture, Its Inspiration and Divine Interpretation" the Constitution states:

11. Those divinely revealed realities which are contained and presented in Sacred Scripture have been committed to writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. For holy mother Church, relying on the belief of the Apostles (cf. John 20:31; 2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Peter 1:19–20, 3:15–16), holds that the books of both the Old and New Testaments in their entirety, with all their parts, are sacred and canonical because written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they have God as their author and have been handed on as such to the Church herself.[6] In composing the sacred books, God chose men and while employed by Him [7] they made use of their powers and abilities, so that with Him acting in them and through them,[8] they, as true authors, consigned to writing everything and only those things which He wanted.[9] Therefore, since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings [10] for the sake of salvation. Therefore "all Scripture is divinely inspired and has its use for teaching the truth and refuting error, for reformation of manners and discipline in right living, so that the man who belongs to God may be efficient and equipped for good work of every kind" (2 Tim. 3:16–17, Greek text).

12. However, since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion, [11] the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words.

To search out the intention of the sacred writers, attention should be given, among other things, to "literary forms". For truth is set forth and expressed differently in texts which are variously historical, prophetic, poetic, or of other forms of discourse. The interpreter must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express and actually expressed in particular circumstances by using contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture.[12] For the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert, due attention must be paid to the customary and characteristic styles of feeling, speaking and narrating which prevailed at the time of the sacred writer, and to the patterns men normally employed at that period in their everyday dealings with one another. [13] no less serious attention must be given to the content and unity of the whole of Scripture if the meaning of the sacred texts is to be correctly worked out. The living tradition of the whole Church must be taken into account along with the harmony which exists between elements of the faith. It is the task of exegetes to work according to these rules toward a better understanding and explanation of the meaning of Sacred Scripture, so that through preparatory study the judgment of the Church may mature. For all of what has been said about the way of interpreting Scripture is subject finally to the judgment of the Church, which carries out the divine commission and ministry of guarding and interpreting the word of God.[14]

13. In Sacred Scripture, therefore, while the truth and holiness of God always remains intact, the marvelous "condescension" of eternal wisdom is clearly shown, "that we may learn the gentle kindness of God, which words cannot express, and how far He has gone in adapting His language with thoughtful concern for our weak human nature". [15] For the words of God, expressed in human language, have been made like human discourse, just as the word of the eternal Father, when He took to Himself the flesh of human weakness, was in every way made like men.

The Old Testament (14–16)

In Chapter IV, Dei Verbum affirms the saying of Augustine that "the New Testament is hidden in the Old, and that the Old Testament is manifest in the New" (DV 16).[16]

The New Testament (17–20)

In Chapter V under the heading "The New Testament" the Constitution states among other points:

18. It is common knowledge that among all the Scriptures, even those of the New Testament, the Gospels have a special preeminence, and rightly so, for they are the principal witness for the life and teaching of the incarnate Word, our savior.

The Church has always and everywhere held and continues to hold that the four Gospels are of apostolic origin. For what the Apostles preached in fulfillment of the commission of Christ, afterwards they themselves and apostolic men, under the inspiration of the divine Spirit, handed on to us in writing: the foundation of faith, namely, the fourfold Gospel, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.[17]

19. Holy Mother Church has firmly and with absolute constancy held, and continues to hold, that the four Gospels just named, whose historical character the Church unhesitatingly asserts, faithfully hand on what Jesus Christ, while living among men, really did and taught for their eternal salvation until the day He was taken up into heaven (see Acts 1:1). Indeed, after the Ascension of the Lord the Apostles handed on to their hearers what He had said and done. This they did with that clearer understanding which they enjoyed[18] after they had been instructed by the glorious events of Christ's life and taught by the light of the Spirit of truth [19] The sacred authors wrote the four Gospels, selecting some things from the many which had been handed on by word of mouth or in writing, reducing some of them to a synthesis, explaining some things in view of the situation of their churches and preserving the form of proclamation but always in such fashion that they told us the honest truth about Jesus [20]For their intention in writing was that either from their own memory and recollections, or from the witness of those who "themselves from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the Word" we might know "the truth" concerning those matters about which we have been instructed (see Luke 1:2–4).[21]

Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church

"Easy access to Sacred Scripture should be provided for all the Christian faithful."[22] To this end the Church sees to it that suitable and correct translations are made into different languages, especially from the original texts of the sacred books. Frequent reading of the divine Scriptures is encouraged for all the Christian faithful, and prayer should accompany the reading of Sacred Scripture, "so that God and man may talk together".[23] Some are ordained to preach the Word, while others reveal Christ in the way they live and interact in the world.[24]

Scholarly opinion

The schema, or draft document, prepared for the first council session (October–December 1962) reflected the conservative theology of the Holy Office under Cardinal Ottaviani. Pope John intervened directly to promote instead the preparation of a new draft which was assigned to a mixed commission of conservatives and progressives, and it was this on which the final document was based.[25]

Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, identified three overall themes in Dei verbum: (1) the new view of the phenomenon of tradition;[26] (2) the theological problem of the application of critical historical methods to the interpretation of Scripture;[27] and (3) the biblical movement that had been growing from the turn of the twentieth century.[28]

Regarding article 1 of the preface of Dei verbum, Ratzinger wrote: "The brief form of the Preface and the barely concealed illogicalities that it contains betray clearly the confusion from which it has emerged."[29]

Biblical infallibility and inerrancy

The Catechism states that "the books of Scripture firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided to the Sacred Scriptures."[30]

Nevertheless, the Catechism clearly states that "the Christian faith is not a 'religion of the book.' Christianity is the religion of the 'Word' of God, a word which is 'not a written and mute word, but the Word is incarnate and living'. If the Scriptures are not to remain a dead letter, Christ, the eternal Word of the living God, must, through the Holy Spirit, 'open [our] minds to understand the Scriptures.'" [31]

The Catechism goes on to state that "In Sacred Scripture, God speaks to man in a human way. To interpret Scripture correctly, the reader must be attentive to what the human authors truly wanted to affirm, and to what God wanted to reveal to us by their words." [32]

"But since Sacred Scripture is inspired, there is another and no less important principle of correct interpretation, without which Scripture would remain a dead letter. 'Sacred Scripture must be read and interpreted in the light of the same Spirit by whom it was written.'" [33]

There was a controversy during the Council on whether the Roman Catholic Church taught biblical infallibility or biblical inerrancy.[34] Some have interpreted Dei verbum as teaching the infallibility position, while others note that the conciliar document often quotes previous documents such as Providentissimus Deus and Divino afflante Spiritu that clearly teach inerrancy.[35]

Dei verbum has sometimes been compared to the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, which expounds similar teachings, characteristic of many evangelical Protestants.

Footnotes

- Cheney, David M. "Second Vatican Council". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "Dei verbum". vatican.va (in Latin).

- Dei verbum, §9.

- Hamm, Dennis SJ, "Dei verbum an orientation and review", Creighton University

- S.J., Avery Cardinal Dulles, Church and Society: The Laurence J. McGinley Lectures, 1988–2007 (p. 69). Fordham University Press.

- Footnote: Cf. Vatican Council I, Const. dogm. de fide catholica, c. 2 (de revelatione): Denz. 1787 (3006). Bibl. Commission, Decr. 18 June 1915: Denz. 2180 (3629); EB 420: Holy Office, Letter, 22 December 1923; EB499.

- Footnote: Cf. Pius XII, Encycl. Divino afflante Spiritu, 30 September 1943; AAS 35 (1943), p.314; EB 556.

- Footnote: In and by man: cf. Heb. 1:1; 4:7 (in); 2 Sam 23:2; Mt 1:22 and passim (by); Vatican Council I, schema de doctr. cath., note 9; Coll. Lac., VII, 522.

- Footnote: Leo XIII, Encycl. Providentissimus Deus, 18 November 1893: Denz. 1952 (3293); EB 125.

- Footnote: Cf. St. Augustine, Gen. ad Litt., 2, 9, 20: PL 34, 270–271; Epist. 82, 3: PL 33, 277; CSEL 34, 2, p.354. – St. Thomas, De Ver. q. 12, a. 2, C. – Council of Trent, Session IV, de canonicis Scripturis: Denz. 783 (1501) – Leo XIII, Encycl. Providentissimus: EB 1121, 124, 126–127. – Pius XII, Encycl. Divino afflante: EB 539.

- Footnote: St. Augustine, De Civ. Dei, XVII, 6. 2: PL 41, 537: CSEL XL, 2, 228.

- Footnote: St. Augustine, De Doctr. Christ., III, 18, 26; PL 34, 75–76.

- Footnote: Pius XII, loc. cit.: Denz. 2294 (3829–2830); EB 557–562.

- But, since Holy Scripture must be read and interpreted in the sacred spirit in which it was written,

- Footnote: Cf. Benedict XV, Encycl. Spiritus Paraclitus, 15 September 1920: EB 469. St. Jerome, In Gal. 5, 19–21: PL 26, 417 A.

- But, since Holy Scripture must be read and interpreted in the sacred spirit in which it was written,

- Footnote: Cf. Vatican Council I, Const. dogm. de fide catholica, c. 2 (de revelatione): Denz. 1788 (3007).

- Footnote: St. John Chrysostom, In Gen. 3, 8 (hom. 17, 1): PG 54, 134. Attemperatio corresponds to the Greek synkatábasis.

- S.J., Avery Cardinal Dulles, Church and Society: The Laurence J. McGinley Lectures, 1988-2007 (p. 70). Fordham University Press

- Footnote: Cf. St. Irenaeus, Adversus haereses III, 11, 8: PG 7, 885; ed. Sagnard, p. 194.

- Footnote: Cf. Jn 2:22; 12–16; cf. 14:26; 16:12–13; 7:39.

- Footnote: Cf. Jn 14:26; 16:13.

- Footnote: Cf. The Instruction Sacra Mater Ecclesia of the Pontifical Biblical Commission: AAS 56 (1964), p. 715.

- For the Latin text of sections 18 and 19 and the relevant sections of Sancta Mater Ecclesia see Bernard Orchard OSB, Dei verbum and the Synoptic Gospels, Appendix (1990).

- Pope Paul VI, "Dei verbum", §22, 18 November 1965 Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Dei verbum, §25.

- Sheffer, Ed., "Summary of Dei neggaverbum", St. Thomas the Apostle Church, Tucson, Arizona

- The HarperCollins Encyclopedia of Catholicism, San Francisco, 1995, p. 425: Raymond Brown, The Critical Meaning of the Bible, Paulist Press (1981), page 18

- Vorgrimler, vol. III, p. 155.

- Vorgrimler, vol. III, p. 157.

- Vorgrimler, vol. III, p. 158.

- Vorgrimler, vol. III, p. 167.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church – Sacred Scripture

- Catechism of the Catholic Church – Sacred Scripture

- Catechism of the Catholic Church – Sacred Scripture

- Catechism of the Catholic Church – Sacred Scripture

- The Inerrancy of Scripture and the Second Vatican Council

- Rome's Battle for the Bible

Works cited

- "Dei verbum". vatican.va.

- Commentary on the Documents of Vatican II, volume III, edited by Herbert Vorgrimler, chapter on the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, written by Joseph Ratzinger, Aloys Grillmeier, and Béda Rigaux, Herder and Herder, New York, 1969.

Further reading

- The Gift of Scripture, "Published as a teaching document of the Bishops' Conferences of England, Wales and Scotland" (2005), The Catholic Truth Society, Ref. SC 80, ISBN 1-86082-323-8.

- Scripture: Dei Verbum (Rediscovering Vatican II), by Ronald D. Witherup, ISBN 0-8091-4428-X.

- Sinke Guimarães, Atila (1997). In the Murky Waters of Vatican II. Metairie: MAETA. ISBN 1-889168-06-8.

- Amerio, Romano (1996). Iota Unum. Kansas City: Sarto House. ISBN 0-9639032-1-7.

- Witherup, Ronald D., The Word of God at Vatican II: Exploring Dei Verbum, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2014.

External links

- Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation – Dei verbum (English translation on the Vatican website)

- Arthur Wells, Bishop Christopher Butler OSB – His Rôle in Dei Verbum, Part 1 – Part 2

- Bernard Orchard OSB, Dei Verbum and the Synoptic Gospels (1990)

- Brian W. Harrison, O.S., On Rewriting the Bible (2002)