Delaware Tercentenary half dollar

The Delaware Tercentenary half dollar (also known as the Swedish Delaware half dollar) was minted during 1937 (although dated 1936) to commemorate 300th anniversary of the first successful European settlement in Delaware. The obverse features the Swedish ship the Kalmar Nyckel which sent the first settlers to Delaware, while the reverse depicts Old Swedes Church, claimed to be the oldest Protestant church in the United States. Confusingly, while the coins are dated "1936" on the obverse and the reverse also has the dual date of "1638" and "1938", the coins were actually struck in 1937.[1]

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm (1.20 in) |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1937 |

| Mintage | 25,015 including 15 pieces for the Assay Commission and 4,022 later melted. |

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at Philadelphia Mint without mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | Old Swedes Church |

| Designer | Carl L. Schmitz |

| Design date | 1936 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Kalmar Nyckel |

| Designer | Carl L. Schmitz |

| Design date | 1936 |

Background

A first attempt at European settlement in what is now Delaware occurred in 1631 near Lewes; the incipient colony was destroyed by the Native Americans. The Swedes tried in 1638 with two ships, the Kalmar Nyckel and the Fogel Grip, an expedition commanded by Peter Minuit, famed for his purchase of Manhattan Island but later dismissed by the Dutch. They settled at the present site of Wilmington. The colony of New Sweden, established to profit from the fur trade, was on land claimed by the Dutch in New Jersey and the English in Maryland; the conflict over the next years was primarily with the latter. Intermittent warfare ended with the arrival of an overwhelming Dutch fleet in 1655. In 1664, though, the English conquered New Netherland, the Dutch possessions in the Middle Atlantic states, and in 1682, Delaware was granted to William Penn, the new proprietor of Pennsylvania.[2] Delaware became one of the original Thirteen Colonies, and, in 1787, was the first state to ratify the Constitution.[3]

Until 1954, the entire mintage of each commemorative coin issues issue was sold by the government at face value to a group named by Congress in authorizing legislation, who then tried to sell the coins at a profit to the public. The new pieces then entered the secondary market, and in early 1936 all earlier commemoratives sold at a premium to their issue prices. The apparent easy profits to be made by purchasing and holding commemoratives attracted many to the coin collecting hobby, where they sought to purchase the new issues. The growing market for such pieces led to many commemorative coin proposals in Congress, to mark anniversaries and benefit (it was hoped) worthy causes.[4] Unlike other commemoratives of the time, the reason for minting the Delaware half dollar was greed; it was felt that the 300th anniversary of the first settlement in Delaware, the first state, was worthy of commemoration.[5] The designated organization to purchase the Delaware half dollars was the Delaware Swedish Tercentenary Commission (DSTC), acting though its president.[6]

Legislation

A joint resolution authorizing 20,000 commemorative half dollars for the 300th anniversary of Swedish settlement in Delaware was introduced into the United States Senate by Joseph F. Guffey of Pennsylvania on March 4, 1936. It was referred to the Committee on Banking and Currency.[7] and was one of several commemorative coin bills to be considered on March 11, 1936, by a subcommittee led by Colorado's Alva B. Adams.[lower-alpha 1][8]

Senator Adams had heard of the commemorative coin abuses of the mid-1930s, with issuers increasing the number of coins needed for a complete set by having them issued at different mints with different mint marks; authorizing legislation placed no prohibition on this.[9] Lyman W. Hoffecker, a Texas coin dealer and official of the American Numismatic Association, testified and told the subcommittee that some issues, like the Oregon Trail Memorial half dollar, first struck in 1926, had been issued over the course of years with different dates and mint marks. Other issues had been entirely bought up by single dealers, and some low-mintage varieties of commemorative coins were selling at high prices. The many varieties and inflated prices for some issues that resulted from these practices angered coin collectors trying to keep their collections current.[10]

No further action was taken on that joint resolution, but on March 16, Guffey and Delaware's Daniel O. Hastings introduced a new one. Among the changes made were requiring that the president of the Delaware Tercentenary Commission sign off on coin orders from the Mint, rather than requiring the chairman of the commission's coinage committee to be the one responsible.[7][11] Nevertheless, when Adams reported the joint resolution back to the Senate on March 26, he attached an amendment entirely rewriting the bill, and explained in an accompanying report, "The bil above referred to contains certain provisions which the committee recommend be eliminated not only from such bil but also from all subsequent bills relating to the issuance of commemorative coins. One of these provisions would have allowed the coins to be issued at several mints and another provision would have permitted the coins to be issued at such times and in such amounts as the committee or other body in charge of the commemorative exercises might determine."[12] He stated that "the committee recommend that the issuance of the coins be limited to one mint to be selected by the Director of the Mint and that not less than 5,000 such coins be issued at any one time".[12]

The joint resolution was brought to the Senate floor on March 27, 1936, the first of six coinage bills being considered one after the other. Like the others, it was amended and passed without recorded discussion or dissent.[13] In the House of Representatives, the bill was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. That committee reported back on April 16, with an amendment that raised the minimum mintage to 25,000.[14] On April 30, J. George Stewart of Delaware brought the bill to the House floor and it passed without discussion or dissent.[15]

As the two houses had not passed identical versions, this sent the bill back to the Senate. On May 4, Adams moved that the Senate agree to the House amendment, which it did;[16] the bill became law, authorizing not fewer than 25,000 half dollars, with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 15, 1936.[6] The bill was signed despite the opposition of the Treasury Department, which prepared a draft veto message.[17] The striking was only allowed to take place at a single mint, with all pieces to be dated 1936 and to be issued by the Mint within a year of the bill's enactment, thus not later than May 15, 1937.[5]

Preparation

On May 18, 1936, the DSTC's general secretary, George Ryden, wrote to the Assistant Director of the Mint, Mary M. O'Reilly, requesting procedural information, stating that the commission might order as many as 50,000 coins in two tranches, and informing her that the DSTC planned to elect the design for the coin by open competition.[17] This was not the usual way of proceeding for a committee charged with finding a design for a commemorative, who more usually picked an artist by other means. The competition was judged by Mint Chief Engraver John R. Sinnock and noted sculptor Dr. Robert Tait McKenzie. Over 40 entries were submitted, all vying for both a $500 prize and the honor of being the final design for the coin, and one by Carl L. Schmitz, an American of German and French descent, was chosen.[5] Schmitz chose the Kalmar Nyckel as his subject for one side of the coin, and the Old Swedes Church in Wilmington, Delaware for the other.[18]

The designs were received by the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and on November 5, 1936 prints of them were sent to its sculptor-member, Lee Lawrie.[18] The commission was charged by a 1921 executive order by President Warren G. Harding with rendering advisory opinions on public artworks, including coins.[19] The DSTC was withholding the name of the artist pending CFA approval of the designs, and in a letter of November 9 to the CFA secretary, H.R. Caemmerer, Lawrie staled, "these models seem to me to be made by one who understands the business—they are excellent."[20] He was unsure what the designs represented, though, and asked for clarification. DSTC chairman C.L. Ward responded to Caemmerer on November 14, disclosing Schmitz's name, explaining the designs, and wanting modifications to the shape of the church. On December 14, the CFA approved the design, subject to Ward's concerns being addressed. Schmitz modified his models, which were reduced to coin-sized hubs by the Medallic Art Company of New York.[20]

Design

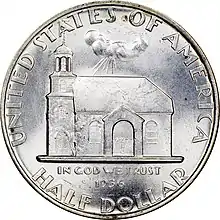

Mint records consider the side with the church as the obverse, though the DSTC considered it to be the side with the ship; numismatic author Q. David Bowers wrote that collectors have come to agree with the Mint,[21] though Anthony Swiatek, in his 2012 volume on commemoratives, note that some collectors and dealers dissent.[22] Consecrated in 1699, Old Swedes Church has been described as the oldest Protestant church building in the United States still used for worship.[23] Swiatek and Walter Breen, in their earlier volume, note that the church is depicted as it appeared, not in 1699, but following the addition of a tower and belfry in 1802. Above the church the Sun is depicted with its rays piercing the clouds; Swiatek and Breen suggested this symbolic of divine protection despite adversity.[24] The year 1936 appears, as required by the authorizing law, and between the year and the church is the motto, IN GOD WE TRUST. Ringing the design are the name of the issuing country, and the coin's denomination.[25]

The reverse depicts the Kalmar Nyckel—the name means "Key of Kalmar". The depiction on the coin is based on a Swedish-made copy of the model of the ship in the Marinmuseum, the Swedish Naval Museum. The artist's initials, CLS, are to the right of the ship. Under the waves beneath the ship are LIBERTY and E PLURIBUS UNUM, along with the anniversary dates. The year of minting, 1937, does not appear on the coin despite the presence of the dates 1936 and 1938. Separating the dates beneath the ship from each other and from the words DELAWARE TERCENTENARY that otherwise ring the design are three diamonds. These symbolize the three counties (Kent, New Castle and Sussex) of Delaware, "The Diamond State".[25]

In his 1938 monograph on commemorative coins, David Bullowa wrote of the Delaware half dollar, "The design of this coin is effective and simple. The legends are particularly clear, and the coin as a whole is very tastefully wrought".[26] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule wrote of the Delaware half dollar in his book on American coins and medals, "the design comes off with boldness and simplicity. Ships and architecture can offer more pitfalls than they do joys, but Schmitz, wisely, has presented plain solids and solid, yet unusual lettering. Even the triad of standard [national] mottoes are apportioned to both sides, to their exergues, in such a manner as to avoid irritation. Although offering nothing new, this coin speaks forcefully amid its contemporaries."[27]

Distribution

A total of 25,015 coins were minted in March 1937 at the Philadelphia Mint, with the 15 pieces above the even thousands set aside for inspection and testing at the following year's meeting of the annual Assay Commission. The coins were sold by the DSTC through the Equitable Trust Company of Wilmington at $1.75 per piece,[5][28] Coins that had been ordered in advance were distributed in late March and in April.[29] Of the 25,000 coins minted, 20,978 were sold, with the 4,022 remaining pieces returned to the Mint for redemption and melting.[5][1]

Proceeds from the coin were used to fund local celebrations of the anniversary, which were held in Sweden and in the United States in 1938. Sweden also issued a commemorative coin for the anniversary, a 2-kronor coin depicting the Kalmar Nyckel.[26] These were promoted by American coin dealers such as Wayte Raymond of New York, who was involved in the US distribution of the Swedish coin, as collectable alongside the Delaware half dollar.[21] There were also several privately-produced medals, and a new stamp from the United States Post Office Department was issued at Wilmington on June 27, 1938.[lower-alpha 2][30]

By 1940 the Delaware piece sold for about $1.50 in uncirculated condition, though this went up to $2.75 by 1950, $18 by 1960, and $350 by 1985.[31] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the coin for between $220 and $375, depending on condition.[32] Two exceptional specimens sold for $7,475 in 2008 and in 2011.[5] The original coin holder in which up to five Delaware half dollars were sent to purchasers are worth from $75 to $125, and if accompanied by original mailing envelope up to $200, depending on condition.[33]

Notes

- In addition to the Bridgeport piece, they were: the Wisconsin Territorial Centennial half dollar, Bridgeport Centennial half dollar, Rhode Island Tercentenary half dollar, New Rochelle 250th Anniversary half dollar, House and Senate versions of the Long Island Tercentenary half dollar, and an unsuccessful proposal for a half dollar honoring William Henry Harrison. In addition, there was a proposal for a new design for the multi-year Arkansas Centennial half dollar, which would pass, and a similar request for the Texas Centennial half dollar, which would fail alongside bills for commemorative medals for Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, a proposal to revive the three-cent nickel, and a bill to declare it the policy of the U.S. to strike commemorative medals instead of commemorative coins.[8]

- The three-cent stamp has Scott Catalogue number 836.[30]

References

- "1936 Delaware Tercentenary Half Dollar Commemorative Coin". Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Slabaugh, pp. 135–136.

- Swiatek & Breen, p. 79.

- Bowers, pp. 62–63.

- "1936 Delaware 50C MS Silver Commemoratives". www.ngccoin.com. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Flynn, p. 355.

- "74 S. J. Res. 224". March 4, 1936. Retrieved February 28, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- Senate hearings, pp. title page, 1–2.

- Senate hearings, pp. 11–12.

- Senate hearings, pp. 18–23.

- "74 S. J. Res. 231". March 26, 1936. Retrieved February 28, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- Senate report, p. 1.

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 4489–4490 (March 27, 1936)

- House report, p. 1.

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 6495 (April 16, 1936)

- 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 6611 (May 4, 1936)

- Flynn, p. 272.

- Flynn, p. 273.

- Taxay, pp. v–vi.

- Taxay, p. 210.

- Bowers, p. 348.

- Swiatek, p. 328.

- Swiatek, pp. 328–329.

- Swiatek & Breen, pp. 79–81.

- Swiatek, p. 329.

- Bullowa, p. 163.

- Vermeule, pp. 200–201.

- Bowers, p. 349.

- "Delaware Swedish Tercentenary half dollar". The Numismatist: 410. May 1937.

- Swiatek & Breen, p. 82.

- Bowers, p. 350.

- Yeoman, p. 1090.

- Swiatek, pp. 330–331.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Bullowa, David M. (1938). "The Commemorative Coinage of the United States 1892–1938". Numismatic Notes and Monographs. New York: American Numismatic Society (83): i–192. JSTOR 43607181. (subscription required)

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- United States House of Representatives Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures (April 16, 1936). To authorize the coinage of 50-cent pieces in commemoration of the three-hundredth anniversary of the landing of the Swedes in Delaware. United States Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)(subscription required)

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (March 11, 1936). Coinage of commemorative 50-cent pieces. United States Government Printing Office.(subscription required)

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (March 26, 1936). Authorize the coinage of 50-cent pieces in commemoration of the three-hundredth anniversary of the landing of the Swedes in Delaware – via ProQuest. (subscription required)

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links

Media related to Delaware Tercentenary half dollar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Delaware Tercentenary half dollar at Wikimedia Commons