Depsang Bulge

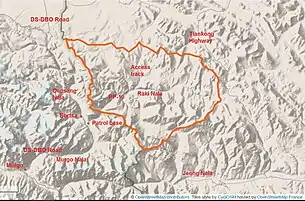

The Depsang Bulge is a 900 square kilometre area[1] of mountain terrain in the disputed Aksai Chin region, which was conceded to India by China in 1960 but remains under Chinese occupation since the 1962 Sino-Indian War.[3] The area is immediately to the south of Depsang Plains and encloses the basin of the Raki Nala, a stream originating in the Aksai Chin region and flowing west to drain into Ladakh's Shyok River. Arguably, the area is of strategic importance to both the countries, sandwiched by strategic roads linking border outposts. Since 2013, China has made attempts to push the Line of Actual Control further west into the Indian territory, threatening India's strategic road.

Depsang Bulge | |

|---|---|

Depsang Bulge Location in the Kashmir region | |

| Coordinates: 35°9′N 78°10′E | |

| Country | India (claimed) China (controlled) |

| Province/Region | Ladakh Xinjiang |

| Area | |

| • Total | 900 km2 (300 sq mi) |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 19 km (12 mi) |

| • Width | 5 km (3 mi) |

| Elevation | 5,000 m (16,000 ft) |

Geography

The Depsang Bulge is immediately to the south of Depsang Plains.[lower-alpha 2] The "bulge", in theoretical Indian territory (had China's 1960 claim line been implemented), encloses the basin of the Raki Nala ("Tiannan River" to the Chinese), one of five rivers that drains into the Shyok River after rising in Aksai Chin.[lower-alpha 3] Near the campsite of Burtsa, on the historical Ladakh–Xinjiang trade route, the Raki Nala merges with Depsang Nala from north and forms the Burtsa Nala. All the streams bring snow-melt water, reaching the highest volume at midday, and diminishing to practically nothing at other times.

Based on various Indian news reports, it would appear that the Depsang Bulge area is 19 km long east to west and about 5 km wide, giving an area of roughly 900 sq. km.[2][1] Burtsa is at an elevation of 4570 metres,[4] the source of Raki Nala at 5300 metres, and the surrounding hills rise up to 5500–5600 metres. Just beyond the hills to the south is another nala called the Jeong Nala ("Jiwan Nala" to the Indian military, "Nacho Chu" in older maps), which does not have a "bulge".

Chinese claim lines

.jpg.webp)

The so-called 1956 claim line of China is part of the "Big map of the People's Republic of China" published in 1956. Scholars point out the varying boundaries shown in Chinese maps between 1947 and 1960. But the special significance of the 1956 map is that the Chinese premier Zhou En-lai certified it to the Indian premier Jawaharlal Nehru in a 1959 letter as being a correct map.[5] The Chinese boundary in this map ran east of all but one of the rivers that drain into the Shyok River.

In June 1960, when the Chinese delegates met the Indian delegates for border discussions, they revealed a new expanded boundary, which has come to be called "the 1960 claim line".[6][7] This line dissected all the rivers that drain into Shyok, except for the Raki Nala. Why Raki Nala should have been singled out for this special treatment has not been explained. But the resulting "bulge" in the Indian territory around the Raki Nala has been dubbed the Depsang Bulge in popular parlance.

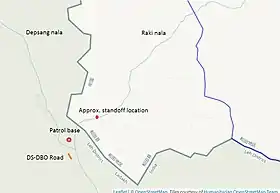

Prior to the 1962 war, Indian Army had established half a dozen posts on the hills to the north of the Depsang Bulge, mostly of platoon to section strength, manned by Jammu and Kashmir Militia (Ladakh Scouts). The Chinese PLA launched its attack on 20 October with overwhelming strength, a superiority of 10 to 1 in numbers, and eliminated most of them. The remaining ones were recalled.[8] The Chinese forces advanced to their 1960 claim line in most locations. But at Depsang Bulge, they advanced further, "straightening out the bulge".[3] Thus a third line emerged, from the ceasefire line of 1962 (the orange line in Map 2, and the blue line in Map 3).

Notes

- The Line of Actual Control is that documented by the contributors to the OpenStreetMap as of January 2021. OpenStreetMap aims to represent the "ground situation". In this case, the line seems to have been drawn based on the road access available to the two sides.

- Contrary to reports in the popular press, the area is not part of the Depsang Plains themselves. It is wholly mountain terrain adjoining the Depsang Plains to the south.

- The other rivers of similar disposition are the Chip Chap River, Jeong Nala, Galwan River and the Chang Chenmo River. China's 1956 claim line steered clear of all these rivers except for the Chang Chenmo, which was dissected at the Kongka Pass. The 1960 claim line cut through all of them except the Raki Nala.

References

- Sushant Singh, What Rajnath Left Out: PLA Blocks Access to 900 Sq Km of Indian Territory in Depsang, The Wire, 17 September 2020. "Of the more than 1,000 square kilometres in Ladakh along the LAC now under Chinese control after tensions erupted in May, the scale of Chinese control in Depsang alone is about 900 square kilometres."

- Line Of Actual Control: China And India Again Squabbling Over Disputed Himalayan Border, International Business Times, 3 May 2013. "This past week, media reports said that in mid-April a small platoon of China’s People’s Liberation Army soldiers invaded an area in the Himalayan mountains, entering roughly 19 kilometers (11 miles) into Indian territory and setting up camp."

- P. J. S. Sandhu, It Is Time to Accept How Badly India Misread Chinese Intentions in 1962 – and 2020, The Wire, 21 July 2020. "However, there was one exception and that was in the Depsang Plain (southeast of Karakoram Pass) where they seemed to have overstepped their Claim Line and straightened the eastward bulge."

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012).

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 103: 'It is important to note that Chou En-lai, in a letter of December 17, 1959, stated that the 1956 map "correctly shows the traditional boundary between the two countries in this sector."'

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 103.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 89: "As a matter of strategy, Mehta [Indian lead] sought to have the Chinese record their Western Sector claims on an authoritative map or a list of map coordinates. That way the conferees could see what the discrepancies between the claims of the two sides actually were."

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi, 1962 from the Other Side of the Hill (2015), p. 52–53.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012), Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged, New Delhi: Rupa Publications – via Academia.edu

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Sandhu, P. J. S.; Shankar, Vinay; Dwivedi, G. G. (2015), 1962: A View from the Other Side of the Hill, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-84464-37-0

Further reading

- Singh, Mandip (July–September 2013), "Chinese Intrusion into Ladakh: An Analysis" (PDF), Journal of Defence Studies, 7 (3): 125–136

External links

- Depsang Bulge marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Depsang Nala, Raki Nala and Burtsa Nala, marked on OpenStreet Map, retrieved 25 January 2021.