Galwan River

The Galwan River flows from the disputed Aksai Chin region administered by China to the Ladakh region of India. It originates near the caravan campsite Samzungling on the eastern side of the Karakoram range and flows west to join the Shyok River. The point of confluence is 102 km south of Daulat Beg Oldi. Shyok River itself is a tributary of the Indus River, making Galwan a part of the Indus River system.

| Galwan River | |

|---|---|

Mouth of the Galwan River in Ladakh to the west of the Sino-Indian Line of Actual Control | |

| Location | |

| Countries | India |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Ladakh |

| • coordinates | 34.73773°N 78.77799°E |

| Mouth | |

• location | Shyok River |

• coordinates | 34.7491°N 78.1656°E |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Indus River |

| Galwan River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 加勒萬河 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 加勒万河 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Hindi name | |||||||

| Hindi | गलवान नदी | ||||||

The narrow valley of the Galwan River as it flows through the Karakoram mountains has been a flashpoint between China and India in their border dispute. In 1962, a forward post set up by India in the upper reaches of the Galwan Valley caused an "apogee of tension" between the two countries. China attacked and eliminated the post in the 1962 war, reaching its 1960 claim line. In 2020, China attempted to advance further in the Galwan Valley, leading to a bloody clash on 16 June 2020.

Etymology

The river is named after Ghulam Rasool Galwan, a Ladakhi explorer of Kashmiri descent, who accompanied numerous expeditions of European explorers. In 1899, he was part of a British expedition team that was exploring the areas to the north of the Chang Chenmo valley. According to received folklore, the team got caught in a storm and got lost, when Galwan found a way out through the valley that eventually received his name. Harish Kapadia states that this is one of the rare instances where a major geographical feature is named after a native explorer.[1][2][lower-alpha 1]

Geography

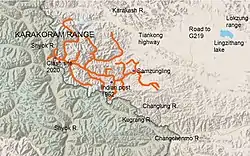

The main section of the Galwan river runs through the entire width of the Karakoram range at this location, for about 30 miles (48 km), where it cuts deep gorges along with its numerous tributaries.[5] At the eastern edge of this 30 mile range, marked by the Samzungling camping ground, the main channel of the Galwan river runs north–south, but several other streams join it as well. To the east of Samzungling, the mountains resemble an elevated plateau, which gradually slope down to the Lingzi Tang Plains in the east. To the west of the channel lie numerous mountains of the Karakoram range, the majority of which are drained by the Galwan river through a multitude of tributaries.

At the northeastern edge of the Galwan River basin, the mountains form a water-parting line, sending some of their waters into the Karakash River basin. To the south of the Galwan river, the Karakoram range divides into two branches, one that lies between the Kugrang and Changlung rivers (both tributaries of Chang Chenmo), and the other to the east of Changlung.[6]

Travel routes

.jpg.webp)

The narrow gorge of the Galwan river prohibited human movement, and there is no evidence of the valley having been used as a travel route. Samzunling however formed an important halting point of a north–south caravan route (the westernmost "Changchenmo route") to the east of Karakoram range. One reaches Samzungling from the Changchenmo valley by following the channel of the Changlung river and crossing over to the Galwan river basin via the Changlung La or the Pangtung Pass.[7] Beyond Samzungling, one follows the Galwan channel to one of its sources, after which the Lingzi Tang plain is entered. The next halting point on the caravan route is Dehra Kompas.[8] Thus the upper Galwan Valley formed a key north–south communication link between the Chang Chenmo valley and the Karakash River basin.[9]

In modern times, the Chinese Wen Jia Road (温加线) traverses this route up to the Galwan River.[10] The eastern route through Nischu now carries the Tiankong Highway (Tianwendian–Kongka highway) and a new Galwan Highway links the two.[11]

Sino-Indian border dispute

.jpg.webp)

The Galwan river is to the west of China's 1956 claim line in Aksai Chin. However, in 1960 China advanced its claim line to the west of the river along the mountain ridge adjoining the Shyok river valley.[12] The Chinese said little by way of justification for this advancement other than to claim that it was their "traditional customary boundary" which was allegedly formed through a "long historical process". The line was altered in the recent past, in their view, only due to "British imperialism".[13][lower-alpha 4]

Meanwhile, India continued to claim the entire Aksai Chin plateau.

1962 standoff

These claims and counterclaims led to a military standoff in the Galwan River valley in 1962. On 4 July, a platoon of Indian Gorkha troops set up a post in the upper reaches of the valley. The post ended up cutting the lines of communication to a Chinese post at Samzungling. The Chinese interpreted it as a premeditated attack on their post, and surrounded the Indian post, coming within 100 yards of the post. The Indian government warned China of "grave consequences" and informed them that India was determined to hold the post at all costs. The post remained surrounded for four months and was supplied by helicopters. According to scholar Taylor Fravel, the standoff marked the "apogee of tension" for China's leaders.[15][16][17][18]

1962 war

By the time the Sino-Indian War started on 20 October 1962, the Indian post had been reinforced by a company of troops. The Chinese PLA bombarded the Indian post with heavy shelling and employed a battalion to attack it. The Indian garrison suffered 33 killed and several wounded, while the company commander and several others were taken prisoner.[15][16] By the end of the war, China reached its 1960 claim line.[12]

2020 skirmish

In summer 2020, India and China have been engaged in a military stand-off at multiple locations along the Sino-Indian border. On 16 June 2020, it was reported that a violent clash took place between troops of the two countries near India's Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan Valley. Twenty Indian Army soldiers and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers were killed.[20]

Notes

- The folklore dates the event to 1892–93 when Galwan accompanied an expedition of Lord Dunmore.[3] This is almost certainly not correct as Lord Dunmore did not travel through this region.[4] The identity of the 1899 expedition is unknown.

- Map by the US Army Headqurters in 1962. The blue line indicates the position in 1959, the purple line that in September 1962 prior to the war, and the orange line, which coincides with the dark brown line, the position the end of the war. The dotted lines bound a 20-km demilitarisation zone proposed by China after the war.

- The purple line's intersection with the Galwan valley indicates the location of a Chinese post, whose domination by an Indian post on higher ground caused an "apogee of tension".

- But the military justification for the advancement is not hard to see. The 1956 claim line ran along the watershed dividing the Shyok River basin and the Lingzitang lake basin. It conceded the strategic higher ground of the Karakoram Range to India. The 1960 claim line advanced it to the Karakoram ridge line despite the fact that it did not form a dividing line of watersheds.

References

- Kapadia, Harish (2005), Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs, Indus Publishing, pp. 215–216, ISBN 978-81-7387-181-8

- Gaurav C Sawant, Exclusive: My great grandfather discovered Galwan Valley, China's claims are baseless, says Md Amin Galwan, India Today, 20 June 2020.

- Rasul Bailay, Life and times of the man after whom Galwan river is named, The Economic Times, 20 June 2020.

- The Pamirs: Being a Narrative of a Year's Expedition on Horseback and on Foot Through Kashmir, Western Tibet, Chinese Tartary, and Russian Central Asia. J. Murray. 1894.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 106: "The peculiarity of the Galwan theatre was that the main Karakoram Range in this region is better defined than in the Northern Sector. It is cut by the Galwan river at a place about 30 miles to the east of the Shyok-Galwan river junction."

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 106: "In the south it divides itself into two ranges. One separates the Kugrang river from the Changlung and the other runs along the left bank of the latter and is also called the Nischu Mountains. The first is named Karakoram I and the second Karakoram II."

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), pp. 257–258, 801.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 289.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground & 1963 (117): "The other main route ran through Shamal Lungpa and Samzung Ling [Samzungling] to Dehra Compas, along the upper valley of the Qara Qash River to Qizil Jilga and Chungtosh, through the Qara Tagh Pass and the Chibra valley to Malikshah and Shahidulla."

- Wen Jia Road marked on the OpenStreetMap, retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Galwan Highway marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, pp. 76, 93, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Van Eekelen, Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute (1967), pp. 101–102.

- Buck, Pearl S. (1970), Mandala, New York: The John Day Company, p. 115 – via archive.org

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 287, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, p. 186, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008), Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes, Princeton University Press, p. 186, ISBN 1-4008-2887-2

- Pranab Dhal Samanta, Galwan River Valley: An important history lesson, The Economic Times, 29 June 2020.

-

India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press, Chinese Report, Part 1, pp. 4–5

The location and terrain features of this traditional customary boundary line are now described as follows in three sectors, western, middle and eastern. ... [From the Chip Chap river] It then turns south-east along the mountain ridge and passes through peak 6,845 (approximately 78° 12' E, 34° 57' N) and peak 6,598 (approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 54' N). From peak 6,598 it runs along the mountain ridge southwards until it crosses the Galwan River at approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 46' N. - Editor Of Beijing Mouthpiece Global Times Acknowledges Casualties For China, NDTV, 16 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1967), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China, Springer, ISBN 978-94-017-6555-8

- Van Eekelen, Willem (2015), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China: A New Look at Asian Relationships, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-30431-4

Further reading

- Kler, Gurdip Singh (1995), Unsung Battles of 1962, Lancer Publishers, pp. 111–, ISBN 978-1-897829-09-7

- Galwan, Ghulam Rassul (1923), Servant Of Sahibs, Cambridge, ISBN 81-206-1957-9

External links

- Galwan River basin marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Galwan Highway, Galwan Valley Road marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Xicagou Highway and Wen Jia Road marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Claude Arpi, Latest Developments in the Aksai Chin (covers the Heweitan post of China), 6 October 2013.