Line of Actual Control

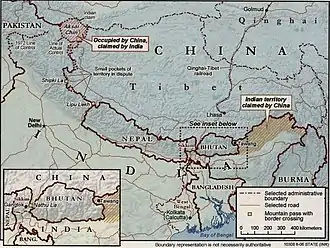

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) is a notional demarcation line that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory in the Sino-Indian border dispute.[1] The term is said to have been used by Zhou Enlai in a 1959 letter to Jawaharlal Nehru.[2] It subsequently referred to the line formed after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and is part of the Sino-Indian border dispute.[3]

There are two common ways in which the term "Line of Actual Control" is used. In the narrow sense, it refers only to the line of control in the western sector of the borderland between the Indian union territory of Ladakh and Chinese Tibet Autonomous Region. In that sense, the LAC, together with a disputed border in the east (the McMahon Line for India and a line close to the McMahon Line for China) and a small undisputed section in between, forms the effective border between the two countries. In the wider sense, it can be used to refer to both the western line of control and the eastern line of control, in which sense it is the effective border between India and the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Overview

The entire Sino-Indian border (including the western LAC, the small undisputed section in the centre, and the McMahon Line in the east) is 4,056 km (2,520 mi) long and traverses five Indian states/territories: Ladakh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh.[4] On the Chinese side, the line traverses the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The term "line of actual control" is said to have been used by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in a 1959 note to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.[2] The demarcation existed as the informal cease-fire line between India and China after the 1962 Sino-Indian War until 1993, when its existence was officially accepted as the 'Line of Actual Control' in a bilateral agreement.[5]

In a letter dated 7 November 1959, Zhou told Nehru that the LAC consisted of "the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west". During the Sino-Indian War (1962), Nehru refused to recognise the line of control: "There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometers from what they call 'line of actual control'. What is this 'line of control'? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September? Advancing forty or sixty kilometers by blatant military aggression and offering to withdraw twenty kilometers provided both sides do this is a deceptive device which can fool nobody."[6]

Zhou responded that the LAC was "basically still the line of actual control as existed between the Chinese and Indian sides on 7 November 1959. To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China."[7]

The term "LAC" gained legal recognition in Sino-Indian agreements signed in 1993 and 1996. The 1996 agreement states, "No activities of either side shall overstep the line of actual control."[8] However clause number 6 of the 1993 Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas mentions, "The two sides agree that references to the line of actual control in this Agreement do not prejudice their respective positions on the boundary question".[9]

The Indian government claims that Chinese troops continue to illegally enter the area hundreds of times every year.[10] In 2013, there was a three-week standoff (2013 Daulat Beg Oldi incident) between Indian and Chinese troops 30 km southeast of Daulat Beg Oldi. It was resolved and both Chinese and Indian troops withdrew in exchange for a Chinese agreement to destroy some military structures over 250 km to the south near Chumar that the Indians perceived as threatening.[11] Later the same year, it was reported that Indian forces had already documented 329 sightings of unidentified objects over a lake in the border region, between the previous August and February. They recorded 155 such intrusions. Later some of the objects were identified as planets Venus and Jupiter by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, appearing brighter as a result of the different atmosphere at altitude and confusion due to the increased use of surveillance drones.[12] In October 2013, India and China signed a border defence cooperation agreement to ensure that patrolling along the LAC does not escalate into armed conflict.[13]

Evolution of the LAC

1956 and 1960 claim lines

LAC of 7 November 1959

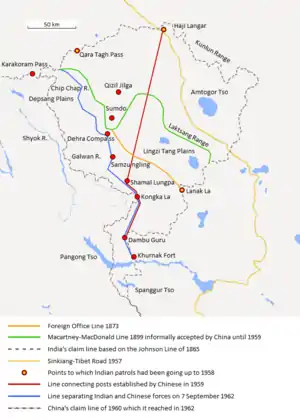

The date of 7 November 1959, on which the Chinese premier Zhou En-lai alluded to the concept of "line of actual control", achieved a certain sanctity in Chinese nomenclature.

Scholar Margaret Fisher states that the Chinese maps had over the years shown a steadily advancing line in the western sector of the Sino-Indian boundary, each of which was identified as "the line of actual control as of 7 November 1959".[14]

On 24 October 1962, after the initial thrust of the Chinese forces in the Sino-Indian War, the Chinese premier Zhou En-lai wrote to the heads of ten Afro-Asian nations outlining his proposals for peace, a fundamental tenet of which was that both sides should undertake not to cross the "line of actual control".[15] This letter was accompanied by certain maps which again identified the "line of actual control as of 7 November 1959". Fisher calls it the "line of actual control as of 7 November 1959" as published in November 1962.[14][16] Scholar Stephen Hoffmann states that the line represented not any position held by the Chinese on 7 November 1959, but rather incorporated the gains made by the Chinese army before and after the massive attack on 20 October 1962. In some cases, it went beyond the territory the Chinese army had reached.[17]

India's understanding of the 1959 line passed through Haji Langar, Shamal Lungpa and Kongka La (the red line shown on the map).[18]

Even though the Chinese-claimed line was not acceptable to India as the depiction of an actual position,[19] it was apparently acceptable as the line from which the Chinese would undertake to withdraw 20 kilometres.[14] Despite the non-acceptance by India of the Chinese proposals, the Chinese did withdraw 20 kilometres from this line, and henceforth continued to depict it as the "line of actual control of 1959".[20]

In December 1962, representatives of six Afro-Asian nations met in Colombo to develop peace proposals for India and China. Their proposals formalised the Chinese pledge of 20-kilometre withdrawal and the same line was used, labelled as "the line from which the Chinese forces will withdraw 20 km."[21][22]

This line was essentially forgotten by both sides till 2013, when the Chinese PLA revived it during its Depsang incursion as a new border claim.[23][lower-alpha 1]

Line separating the forces before 8 September 1962

At the end of the 1962 war, India demanded that the Chinese withdraw to their pre-8 September 1962 positions.[19]

Patrol points

Border terminology

Glossary of border related terms:

- Differing perceptions

- Different views related to where the LAC lies. Similarly, areas of differing perceptions for different views related to areas along the LAC.[24][25][26]

- Patrol Point

- Points along LAC to which troops patrol; as compared to patrolling the entire area.[27][28][29]

- Line of Actual Control (LAC)

- The Line of Actual Control (LAC) is a notional demarcation line that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory in the Sino-Indian border dispute.

- Limits of patrolling

- PPs within the LAC and the patrol routes that join them are known as limits of patrolling.[27]

- Actual LAC

- Limits of patrolling also known as LAC within the LAC or actual LAC.[27]

- Limits of actual control

- Limits of actual control is determined by patrolling points and the limits of actual patrolling.

- Lines of patrolling

- The various patrol routes to the limits of patrolling are called the limits of patrolling.

- Mutually agreed disputed spots

- Both sides agree the location is disputed; as compared to just one side disputing a location.

- Border Personnel Meeting point

- BPMs are locations the LAC where the armies of both countries hold meetings to resolve border issues and improve relations.

See also

- Aksai Chin

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Border Personnel Meeting point

- McMahon Line

- Sino-Indian relations

- Sino-Indian border dispute

- Tibet

Notes

- The claimed line in this location is "new" in that it is well beyond the 1956 and 1960 claim lines of China, the latter having been called the "traditional customary boundary". It is said to be 19 km beyond it, in Indian estimation.

References

- Sushant Singh, Line of Actual Control (LAC): Where it is located, and where India and China differ, The Indian Express, 1 June 2020.

- Hoffman, Steven A. (1990). India and the China Crisis. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780520301726.

- "Line Of Actual Control: China And India Again Squabbling Over Disputed Himalayan Border". International Business Times. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Another Chinese intrusion in Sikkim Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, OneIndia, Thursday, 19 June 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- "Agreement On The Maintenance Of Peace Along The Line Of Actual Control In The India-China Border". stimson.org. The Stimson Center. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Maxwell, Neville (1999). "India's China War". Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- "Chou's Latest Proposals". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- Sali, M.L., (2008) India-China border dispute, p. 185, ISBN 1-4343-6971-4.

- "Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas". United Nations. 7 September 1993. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Chinese Troops Had Dismantled Bunkers on Indian Side of LoAC in August 2011"Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. India Today. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Defense News. "India Destroyed Bunkers in Chumar to Resolve Ladakh Row" Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Defense News. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "India: Army 'mistook planets for spy drones'". BBC. 25 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Reuters. China, India sign deal aimed at soothing Himalayan tension Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Fisher, Margaret W. (March 1964), "India in 1963: A Year of Travail", Asian Survey, 4 (3): 737–745, doi:10.2307/3023561, JSTOR 3023561

- Whiting, Chinese calculus of deterrence (1975), pp. 123–124.

- Karackattu, Joe Thomas (2020). "The Corrosive Compromise of the Sino-Indian Border Management Framework: From Doklam to Galwan". Asian Affairs. 51 (3): 590–604. doi:10.1080/03068374.2020.1804726. ISSN 0306-8374. S2CID 222093756. See Fig. 1, p. 592

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 225.

- Chinese Aggression in Maps: Ten maps, with an introduction and explanatory notes, Publications Division, Government of India, 1963. Map 2.

- Inder Malhotra, The Colombo ‘compromise’, The Indian Express, 17 October 2011. "Nehru also rejected emphatically China's definition of the LAC as it existed on November 7, 1959."

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), Map 6: "India's forward policy, a Chinese view", p. 105.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 226.

- ILLUSTRATION DES PROPOSITIONS DE LA CONFERENCE DE COLOMBO - SECTEUR OCCIDENTAL, claudearpi.net, retrieved 1 October 2020. "Ligne au dela de la quelle les forces Chinoises se retirent de 20 km. selon les propositions de la Conférence de Colombo (Line beyond which the Chinese forces will withdraw 20 km. according to the proposals of the Colombo Conference)"

- Gupta, The Himalayan Face-off (2014), Introduction: "While the Indian Army asked the PLA to withdraw to its original positions as per the 1976 border patrolling agreement, the PLA produced a map, which was part of the annexure to a letter written by Zhou to Nehru and the Conference of African-Asian leaders in November 1959 [sic; the correct date is November 1962], to buttress its case that the new position was well within the Chinese side of the LAC."

- Srivastava, Niraj (24 June 2020). "Galwan Valley clash with China shows that India has discarded the 'differing perceptions' theory". Scroll.in. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Krishnan, Ananth (24 May 2020). "What explains the India-China border flare-up?". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Bedi, Lt Gen (Retd.) AS (4 June 2020). "India-China Standoff : Contracting Options in Ladakh". www.vifindia.org. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Subramanian, Nirupama; Kaushik, Krishn (20 September 2020). "Month before standoff, China blocked 5 patrol points in Depsang". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (13 July 2020). "Patrolling Points: What do these markers on the LAC signify?". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- "India-China LAC Standoff: Know what are patrolling points and what do they signify". The Financial Express. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Gupta, Shishir (2014), The Himalayan Face-Off: Chinese Assertion and the Indian Riposte, Hachette India, ISBN 978-93-5009-606-2

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Whiting, Allen Suess (1975), The Chinese Calculus of Deterrence: India and Indochina, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-96900-5

Further reading

- Unnithan, Sandeep. "Standing up to a stand-off". India Today, 30 May 2020.

- Rup Narayan Das (May 2013) India-China Relations A New Paradigm. IDSA

External links

- Borders of Ladakh, marked on OpenStreetMap represents the Line of Actual Control in the east and south (including the Demchok sector).

- Sushant Singh, Line of Actual Control: Where it is located, and where India and China differ, The Indian Express, 2 June 2020.

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 13 May 2007

- Two maps of Kashmir: maps showing the Indian and Pakistani positions on the border.