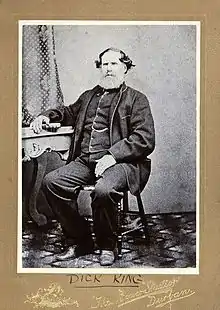

Dick King

Richard Philip King (1811–1871) was an English trader and colonist at Port Natal, a British trading station in the region now known as KwaZulu-Natal. He is best known for a historic horseback ride in 1842, where he completed a journey of 960 kilometres (600 mi) in 10 days, to request help for the besieged British garrison at Port Natal (now the Old Fort, Durban).

Dick King Saviour of Natal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Richard Philip King 26 November 1811 Dursley, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 10 November 1871 (aged 59) Isipingo, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa |

| Resting place | Isipingo Cemetery, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa |

| Spouse | Clara Jane Noon (m.1852) |

| Children | Maria Recordonza, Richard Phillip Henry, Clara Elvira, Francis Richard, Georgina Adelaide, Catherine Tatham, Charles Richard |

| Parents | Philip King, Anna Maria Silverstone |

Early years

Dick King was born on 26 November 1811 in Dursley in the English county of Gloucestershire. He died on 10 November 1871 in Isipingo, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.[1] His family emigrated to the Albany district of the Cape Colony, as part of the 1820 Settlers. In 1828 however his family resettled to the then frontier region of Port Natal, when Dick was about 15 years of age. His first employment was in the clergy. In reverend Francis Owen's company he met Zulu chief Dingane, and also got acquainted with captain Allen Gardiner.

The Voortrekkers

In February , when Dick King was already at Port Natal, Jan Gerritze Bantjes arrived with Petrus Lafras Uys on the "Kommissitrek" from Grahamstown. Bantjes was Uys's scribe. At Port Natal Bantjes did sketches of the bay area, the Berea and around the Mgeni River and made notes for Uys regarding the potential of the bay as a possible new port and capital of the new Boer homeland they were hoping to start. This was done over a period of weeks. Dick King (22) and Jan Gerritze Bantjes (17) went elephant hunting together with Alexander Biggar who was a professional hunter, (Bantjes was fluent in both English and Dutch) and Dick and Jan Gerritze became well acquainted striking up a friendship during the weeks at Port Natal. Together with Johannes Uys, brother of Petrus Uys, they attempted to visit Dingaan on the land grant issue at Uys' request, but due to the Tugela being in full flood, they were forced to return to their laager at the mouth of the Mvoti River and then back to Port Natal without consolidating the Zulu King's perspective on the issue. On their eventual return to Grahamstown in the Cape, it was Bantjes who at Uys's request, drew up the Natalland (Natalialand) Report that would be the catalyst that started the Great Trek from the Cape to the interior and Natal. Bantjes would later write the famous Retief/Dingaan Treaty that would change South African history forever.

Dick King first came to prominence after the 1838 murders of the Voortrekker leader Pieter Retief and his delegation at the kraal of the Zulu chief Dingane. George Champion of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions who heard of the murders notified Port Natal. They sent Dick King to warn his 18-year-old son, George, and others who were 120 miles (200 km) inland at the Voortrekker camps. Dick King departed immediately on foot, accompanied by a number of natives. Despite covering the distance in four days by walking day and night, they arrived just after the van Rensburg voortrekker camp was attacked. They reached the vicinity of the next camp, near present-day Estcourt, just as the attack on it started on 17 February 1838. Though cut off from the Gerrit Maritz laager, he participated in its defence, but was unable to prevent the death of George, who was further inland at the Blaauwekrans river. 600 Boers, including women and children, died in the surprise attacks though others managed to survive the heavy and sustained Zulu onslaughts.

Biggar expedition

The British settlers at the bay, hearing of the latest attacks on the Boers, were determined to make a diversion in their favour. Two Britons from Port Natal, Thomas Halstead and George Biggar, were among those already killed at Dingane's kraal and Blaukraans respectively.

Some 20 to 30 European men, including Dick King, were placed under the command of Robert Biggar. With a following of 1,500 Zulus who deserted from Dingane, they crossed the Tugela river near its mouth and proceeded to uMgungundlovu. After four days they were able to take 7,000 head of cattle from a group of Zulus who fled. The party returned with these cattle to the bay, and discovered that a spy of Dingane had been killed there in their absence.

Once again they set off to Dingane's kraal and reached Ndondakusuka village north of the Tugela on 17 April 1838, which belonged to a captain of Dingane, named Zulu. Here, while questioning a captive, likely a decoy, they were closed in by a strong Zulu force led by Dingane's brother Mpande and his general Nongalaza. The English soon found that retreat was impossible, and blundered by dividing their force to oppose their encirclement. The Zulus made a successful dash which split the forces in two. In the desperate situation that ensued, the British force was overwhelmed. Only Dick King, Richard (or George) Duffy, Joseph Brown, Robert Joyce and about 500 Zulus escaped to the bay.

Pursued by the Zulu force, all the European inhabitants of Port Natal were compelled to take refuge for nine days on the Comet, a British vessel which happened to lie on anchor in the bay. When the Zulus retired, only Dick King and some seven or eight others returned to live at the port. The missionaries, hunters and other traders returned to the Cape.

Defence of Port Natal

In 1842 however the British sent a garrison to Durban under the command of Captain Charlton Smith (who also served at Waterloo). The Voortrekkers had in the meantime consolidated their position inland. They established the Boer republic of Natalia and were intent on expelling the British force from the strategic bay area. This soon led to the Battle of Congella, where the English suffered heavy casualties besides the loss of their artillery. The British garrison had to retreat to their tented camp where their only defence was their trenches and earthworks. The camp was besieged by Andries Pretorius who kept up the small arms and artillery attack continuously, day after day.

Trader George Christopher Cato, who was to become Durban's first mayor, informed Dick King of the situation, who was on the Mazeppa vessel on 25 May. Before daybreak the next morning, King was met by his 16-year-old servant Ndongeni, who brought two horses to the current Salisbury island in the bay. Attached to a boat, the tethered horses swam alongside the boat to the bluff, from where King and Ndongeni escaped.

From Port Natal (now Durban), King and Ndongeni started a heroic horseback ride to convey a request from Captain Smith for immediate reinforcements.[2] The journey involved a ride of 960 kilometres (600 mi) through the wilderness and the fording of 120 rivers to arrive at Grahamstown. Ndongeni was forced to return halfway through the journey, as he had no saddle or bridle. Dick King reached Grahamstown 10 days after leaving Port Natal, a distance normally covered in 17 days. King returned a month after his escape on the Conch, one of the British vessels which carried the relief parties. It arrived at the bay on 24 June, and the reinforcements were in time to save Smith's garrison from imminent surrender or starvation.

Recognition

Ndongeni received a farm at the Mzimkulu river and King a farm at Isipingo for their services. At Isipingo King managed a sugar mill until his death in 1871. Ethel Campbell conducted an interview with Ndongeni in 1911 from which she learned the details of the epic journey. A statue commemorating Dick King and his journey was unveiled on the north shore of Durban Bay (at 29°51′42″S 31°01′31.3″E) on 14 August 1915.

Notes

- Ancestry.com

- Kalley, Jacqueline A. (1986). "Dick King: A Modest Hero" (PDF). Natalia. 16.

Further reading

- Lyster, Lynn (1913). "The Song of 'Ndongeni". Ballads of the Veld-land. London, New York: Longmans, Green and co. p. 30.

References

- Cradle Days of Natal, Graham Mackeurtan

- Dick King, Encarta article (Archived 2009-10-31)

- Dick King, short biography

- Eye witness account, William Wood, Collard & Co., 24 Heerengracht, Cape Town, 1840.

- Information on the Wood, Biggar and Dunn families

- Robert Biggar, The Biggar memorial plaque

- Eye witness account of Biggar expedition, missionary Hewitson's journal