Digestive system of gastropods

The digestive system of gastropods has evolved to suit almost every kind of diet and feeding behavior. Gastropods (snails and slugs) as the largest taxonomic class of the mollusca are very diverse indeed: the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scavengers, filter feeders, and even parasites.

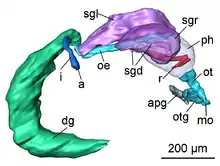

mo - mouth

r - radula

ph - pharynx

sgl and sgr - salivary glands

oe - oesophagus

i - intestine

a - anus

dg - digestive gland.

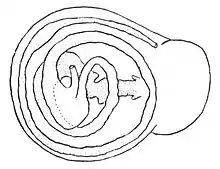

In particular, the radula is often highly adapted to the specific diet of the various group of gastropods. Another distinctive feature of the digestive tract is that, along with the rest of the visceral mass, it has undergone torsion, twisting around through 180 degrees during the larval stage, so that the anus of the animal is located above its head.[1]

A number of species have developed special adaptations to feeding, such as the "drill" of some limpets, or the harpoon of the neogastropod genus Conus. Filter feeders use the gills, mantle lining, or nets of mucus to trap their prey, which they then pull into the mouth with the radula. The highly modified parasitic genus Enteroxenos has no digestive tract at all, and simply absorbs the blood of its host through the body wall.[1]

The digestive system usually has the following parts:

- buccal mass (including the mouth, pharynx, and retractor muscles of the pharynx) and salivary glands with salivary ducts

- oesophagus and oesophagal crop

- stomach, also known as the gastric pouch

- digestive gland, also known as the hepatopancreas

- intestine

- rectum and anus

Buccal mass

The buccal mass is the first part of the digestive system, and consists of the mouth and pharynx. The mouth includes a radula, and in most cases, also a pair of jaws. The pharynx can be very large, especially in carnivorous species.

Many carnivorous species have developed a proboscis, containing the oral cavity, radula, and part of the oesophagus. At rest, the proboscis is enclosed within a sac-like sheath, with an opening at the front of the animal that resembles a true mouth. When the animal feeds, it pumps blood into the proboscis, inflating it and pushing it out through the opening to grasp the gastropod's prey. A set of retractor muscles help pull the proboscis back inside the sheath once feeding is completed.[1]

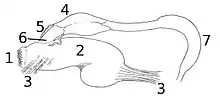

Drawing of the digestive system of Paryphanta busbyi. 1-2 - buccal mass, 1 - mouth, 2 - pharynx, 3 - retractor muscles of the pharynx, 4 - salivary glands, 5 - salivary ducts, 6 - oesophagus, 7 - stomach. |

Drawing of the digestive system of carnivorous Schizoglossa novoseelandica, showing the large pharynx. 1-2 - buccal mass, 1 - mouth, 2 - pharynx, 3 - retractor muscles of the pharynx, 4 - salivary glands, 5 - salivary ducts, 6 - oesophagus and stomach, 7 - intestine, 8 - hepatic ducts. |

Radula

The radula is a chitinous ribbon used for scraping or cutting food.

Jaw

Several herbivorous species, as well as carnivores that prey on sessile animals, have also developed simple jaws, which help to hold the food steady while the radula works on it. The jaw is opposite to the radula and reinforces part of the foregut.[2]

The purely carnivorous the diet, the more the jaw is reduced.[2]

There are often pieces of food in the gut corresponding to the shape of the jaw.[2]

The jaw structure can be ribbed or smooth:

Drawing of the jaw of the Kerry Slug Geomalacus maculosus. The jaw of this species measures about 1 mm and has broad ribs.

Drawing of the jaw of the Kerry Slug Geomalacus maculosus. The jaw of this species measures about 1 mm and has broad ribs. Drawing of the jaw of Macrochlamys indica.

Drawing of the jaw of Macrochlamys indica. Drawing of the jaw of Newcomb's snail.

Drawing of the jaw of Newcomb's snail.

Some species have no jaw.

Salivary glands

Salivary glands plays primary role in the anatomical and physiological adaptations of the digestive system of predatory gastropods.[3] Ducts from large salivary glands lead into the buccal cavity, and the oesophagus also supplies the digestive enzymes that help to break down the food.[1] Salivary secretions lubricate the food and they also contain bioactive compounds.[3]

Oesophagus

The mouth of gastropods opens into an oesophagus, which connects to the stomach. Because of torsion, the oesophagus usually passes around the stomach, and opens into its posterior portion, furthest from the mouth. In species that have undergone de-torsion, however, the oesophagus may open into the anterior of the stomach, which is therefore reversed from the usual gastropod arrangement.[1]

In Tarebia granifera the brood pouch is above the oesophagus.[4]

There is available an extensive rostrum on the anterior part of the oesophagus in all carnivorous gastropods.[5]

Some basal gastropod clades have oesophageal gland.

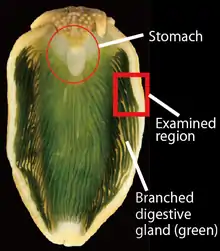

Stomach

In most species, the stomach itself is a relatively simple sac, and is the main site of digestion. In many herbivores, however, the hind part of the oesophagus is enlarged to form a crop, which, in terrestrial pulmonates, may even replace the stomach entirely. In many aquatic herbivores, however, the stomach is adapted into a gizzard that helps to grind up the food. The gizzard may have a tough cuticle, or may be filled with abrasive sand grains.[1]

In the most primitive gastropods, however, the stomach is a more complex structure. In these species, the hind part of the stomach, where the oesophagus enters, is chitinous, and includes a sorting region lined with cilia.[1]

In all gastropods, the portion of the stomach furthest from the oesophagus, called the "style sac", is lined with cilia. These beat in a rotary motion, pulling the food forward in a steady stream from the mouth. Usually, the food is embedded in a string of mucus produced in the mouth, creating a coiled conical mass in the style sac. This action, rather than muscular peristalsis, is responsible for the movement of food through the gastropod digestive tract.[1]

Two diverticular glands open into the stomach, and secrete enzymes that help to break down the food. In the more primitive species, these glands may also absorb the food particles directly and digest them intracellularly.[1]

Hepatopancreas

The hepatopancreas is the largest organ in stylommatophoran gastropods.[7] It produces enzymes, and absorbs and stores nutrients.

Intestine

The anterior portion of the stomach opens into a coiled intestine, which helps to resorb water from the food, producing faecal pellets. The anus opens above the head.[1]

References

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 348–364. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- Mackenstedt U. & Märkel K. (2001-11-29). "Radular Structure and Function". In Barker, G. M (ed.). The Biology of Terrestrial Molluscs. Oxon, UK: CABI Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 9780851993188.

- Ponte, G., & Modica, M. V. (2017). Salivary Glands in Predatory Mollusks: Evolutionary Considerations. Frontiers in Physiology 8: 580. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00580.

- Appleton C. C., Forbes A. T.& Demetriades N. T. (2009). "The occurrence, bionomics and potential impacts of the invasive freshwater snail Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in South Africa". Zoologische Mededelingen 83. http://www.zoologischemededelingen.nl/83/nr03/a04 Archived 2017-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Gerlach, J.; Van Bruggen, A.C. (1998). "A first record of a terrestrial mollusc without a radula". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 64 (2): 249. doi:10.1093/mollus/64.2.249..

- Maeda T., Hirose E., Chikaraishi Y., Kawato M., Takishita K. et al. (2012). "Algivore or Phototroph? Plakobranchus ocellatus (Gastropoda) Continuously Acquires Kleptoplasts and Nutrition from Multiple Algal Species in Nature". PLoS ONE 7(7): e42024. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042024

- Dimitriadis V. K. (2001-11-29). "Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Stylommpatophora". In Barker, G. M (ed.). The Biology of Terrestrial Molluscs. Oxon, UK: CABI Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 9780851993188.

Further reading

- Golding, Rosemary E.; Ponder, Winston F.; Byrne, Maria (2009). "Three-dimensional reconstruction of the odontophoral cartilages of Caenogastropoda (Mollusca: Gastropoda) using micro-CT: Morphology and phylogenetic significance". Journal of Morphology. 270 (5): 558–87. doi:10.1002/jmor.10699. PMID 19107810.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Digestive system of Gastropoda. |