Dime museum

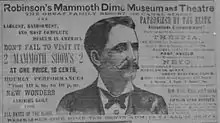

Dime museums were institutions that were popular at the end of the 19th century in the United States. Designed as centers for entertainment and moral education for the working class (lowbrow), the museums were distinctly different from upper middle class cultural events (highbrow). In urban centers like New York City, where many immigrants settled, dime museums were popular and cheap entertainment. The social trend reached its peak during the Progressive Era (c. 1890–1920). Although lowbrow entertainment, they were the starting places for the careers of many notable vaudeville-era entertainers, including Harry Houdini, Lew Fields, Joe Weber, and Maggie Cline.

Baltimore

In Baltimore, Maryland, Peale's Museum is credited as one of the first serious museums in the country. This type of attraction was re-created in the American Dime Museum in 1999, which operated for eight years before closing permanently and auctioning off its exhibits in late February 2007.[1]

Boston

Kimball's Museum and Austin & Stones Museum in Scollay Square were both well-known attractions, the former having a friendly connection to, and sometimes competition with, P. T. Barnum. Barnum and Moses Kimball even shared "Fee Gee Mermaids" on a regular basis.

Cincinnati

Both John James Audubon and sculptor Hiram Powers produced displays for the Western Museum, organized by Dr Daniel Drake in 1818 and continued by Joseph Dorfeuille. "Satan and his Court" wax figures with moving parts and glowing eyes are typical of these displays.

New Orleans

On Canal Street, "Eugene Robinson's Museum and Theater" featured entertainment on the hour and also presented some of its attractions on a nearby riverboat. The common promotion gimmick of a brass band at the front entrance of these Dime Museums featured some of the earliest documented traditional jazz; Robinson's riverboat museum also hired Papa Jack Laine.

New York City

P.T. Barnum purchased Scudder's Dime Museum in 1841 and transformed it into one of the more popular single cultural sites that has existed, Barnum's American Museum. Together, P.T. Barnum and Moses Kimball introduced the so-called "Edutainement", which was a moralistic education realized through sensational freak shows, theater and circus performances, and many other means of entertainment.[2] The first incarnation "American Museum" on Ann Street burned down in 1865. It was relocated further up Broadway, but this venue too, fell victim to fire.

For many years in the basement of the Playland Arcade in Times Square in New York City, Hubert's Museum featured acts such as sword swallower Lady Estelene, Congo The Jungle Creep, a flea circus, a half-man half-woman, and magicians such as Earl "Presto" Johnson. This museum was documented in photography by Diane Arbus. Later, in Times Square, mouse pitchman Tommy Laird opened a dime museum that featured Tisha Booty — "the Human Pin Cushion" — and several magicians, including Lou Lancaster, Criss Capehart, Dorothy Dietrich, Dick Brooks, and others.

Chicago

In 1882, C. E. Kohl and Middleton opened their first Dime Museum in Chicago.[3] It was located at 150 West Madison Street, east of Halsted.

In 1883 they opened a new one at 150 S. Clark Street, near Madison (now 10 South Clark Street) and a third one at 150 W. Madison, opposite Union street.

References

- "American Dime Museum, reportage from the Baltimore museum on its last day of existence". SiteBits. 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2009-08-279 Lisa Rochelle Murray, MA Thesis: P.T. Barnum Presents: The Greatest Classroom on Earth! Historical Inquiry into the Role of Education in Barnum’s American Museum The University of Texas at Austin, 2009

- Ph.d, Neil Gale (2017-05-25). "The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™: Kohl & Middleton's Dime Museums, Chicago, Illinois". The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

Further reading

- McNamara, Brooks. "'A Congress of Wonders:' The Rise and Fall of the Dime Museum." Emerson Society Quarterly 20, no. 3 (1974): 216-232.