Dunfermline Palace

Dunfermline Palace is a ruined former Scottish royal palace and important tourist attraction in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. It is currently, along with other buildings of the adjacent Dunfermline Abbey, under the care of Historic Environment Scotland as a scheduled monument.[1]

Origins

Dunfermline was a favourite residence of many Scottish monarchs. Documented history of royal residence there begins in the 11th century with Malcolm III who made it his capital. His seat was the nearby Malcolm's Tower, a few hundred yards to the west of the later palace. In the medieval period David II and James I of Scotland were both born at Dunfermline.

Dunfermline Palace is attached to the historic Dunfermline Abbey, occupying a site between the abbey and deep gorge to the south. It is connected to the former monastic residential quarters of the abbey via a gatehouse above a pend (or yett), one of Dunfermline's medieval gates. The building therefore occupies what was originally the guest house of the abbey. However, its remains largely reflect the form in which the building was remodelled by James IV around 1500.

History

James IV

In November 1504 Margaret Tudor was in residence when two people were suspected of having plague. James IV was away in the north of Scotland. The queen left for Edinburgh with her household servants , including African women known as the "More lasses", who went first to Inverkeithing. This was a false alarm.[2] Throughout the sixteenth century, Scotland's monarchs and royal family members were frequently in residence.

On 14 June 1562 after dinner at Dunfermline, Mary, Queen of Scots produced a gold ring set with a heart shaped diamond and declared she would send it to Elizabeth with some verses she had written herself in Italian. At this time a meeting of the two queens was discussed.[3]

Anne of Denmark and Prince Charles

James VI stayed at Dunfermline Palace in June 1585 to avoid the plague which raged in Edinburgh. He had a proclamation made to regulate the prices of food, drink, and lodgings for his courtiers in Dunfermline town.[4] In 1589 the palace was given as a wedding present by the king to his bride Anne of Denmark. She gave birth to three of their children in the Palace; Elizabeth (1596),[5] Charles (1600) and Robert (1602), attended by her German physician, Martin Schöner.[6]

The palace staff included the keeper John Gibb, the chamberlains of the estates David Seton of Parbroath, William Schaw, and Henry Wardlaw of Pitreavie, the gardener John Lowrie, the plumber James Coupar, who fixed the lead roofs, and Thomas Walwood, foreman of the coal pits.[7]

Anne of Denmark had a new building built at the Palace completed in 1600, and known as the "Queen's House", or "Queen Anna of Denmark House". This tall building had a driveway known as a "pend" running through its basement level, replacing an earlier gateway.[8] In November 1601 she prepared a lodging for her daughter Princess Elizabeth, but the princess remained at Linlithgow Palace on the king's orders.[9] There was a steep stairwell outside Anne of Denmark's bed chamber, and in March 1602 the English courtier Roger Aston fell down it and was unconscious for three hours.[10]

After the Union of Crowns in 1603, the removal of the Scottish court to London meant that the building came to be rarely visited by a monarch.[11] Prince Charles stayed at Dunfermline for a year in the care of Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline after his mother had gone to England. Jean Drummond, later Countess of Roxburghe had looked after him. Marion Hepburn had been in charge of rocking his cradle. The Prince was slow to learn to walk and was provided with an oak stool with wheels to train him.[12] Dr Henry Atkins wrote from Dunfermline in July 1604 to Anna of Denmark, saying that Prince Charles could now walk the length of the "great chamber" or "longest chamber" several times daily without a stick.[13] Ten tapestries from the royal tapestry collection were still there in 1616, left from the time the infant Prince Charles resided at the Palace.[14]

In 1618 John Taylor, the Water Poet, lodged for a night at the house of the keeper since 1584, John Gibb, which was presumably a part of the palace. Taylor described the site, "the Queenes Palace, a delicate and princely mansion, withall I saw the ruins of an ancient and stately built Abbey, with fair gardens, orchards, meadows, belonging to the Palace."[15]

When Anne of Denmark died in 1619 ownership of the palace passed to Prince Charles. A new great seal of the lordship was made and the "new great house" built by his mother was repaired.[16] The town was devastated by a fire on 25 May 1624 and Prince Charles sent £500 sterling in aid.[17]

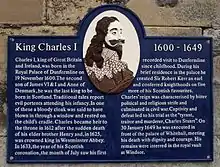

Charles I and Charles II

Charles I returned to Scotland in 1633 for his coronation but only made a brief visit to his place of birth. The last monarch to occupy the palace was Charles II who stayed at Dunfermline in 1650 just before the Battle of Pitreavie. Anne Halkett described meeting him there.[18] Soon afterwards, during the Cromwellian occupation of Scotland, the building was abandoned and by 1708 it had been unroofed.

All that remains of the palace today is the kitchen, its cellars, and the impressive south wall with a commanding prospect over the Firth of Forth to the south.

References

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Dunfermline Abbey (SM90116)". Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. cx, 465, 468: Exchequer Rolls, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1889), pp. 374-5: J. F. D. Shrewsbury, A History of Bubonic Plague in the British Isles (Cambridge, 1970), p. 165.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar of State Papers, Scotland: 1547-1563, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 632, 637.

- David Masson, Register of the Privy Council of Scotland: 1578-1585, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1880), pp. 749, 751.

- M. S. Giuseppi, ed., Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1952), p. 306.

- Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts (Manchester, 2020), pp. 183-4.

- Annie I. Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1593-1595, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 113.

- Ebenezer Henderson, The Annals of Dunfermline and Vicinity, from the Earliest Authentic Period to the Present Time, A.D. 1069-1878 (Dunfermline, 1879), pp. 254-5.

- John Duncan Mackie, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1597-1603, 13:2 (Edinburgh, 1969), p. 895.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1597-1603, 13:2 (Edinburgh, 1969), p. 960 no. 780.

- Dennison, E. Patricia; Stronach, Simon (2007). Historic Dunfermline : archaeology and development. Dunfermline: Dunfermline Burgh Survey. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-9557244-0-4.

- Letters to King James the Sixth from the Queen, Prince Henry, Prince Charles, the Princess Elizabeth (Edinburgh, 1835), pp. lxxxi, lxxxviii

- HMC Salisbury Hatfield, vol. 16, pp. 163-4.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 10, p. 521.

- John Taylor, 'Pennilesse Pilgrimage', All the Workes of John Taylor, the Water Poet (London, 1630), p. 132.

- National Records of Scotland, E42/1, Exchequer Records: Accounts of Lordship of Dunfermline

- HMC Mar & Kellie (London, 1904), p. 122.

- John Gough Nichols, Autobiography of the Lady Halkett (London, 1875), pp. 59-61.

.svg.png.webp)