East–West dichotomy

In sociology, the East–West dichotomy is the perceived difference between the Eastern and the Western worlds. Cultural and religious rather than geographical in division, the boundaries of East and West are not fixed, but vary according to the criteria adopted by individuals using the term.

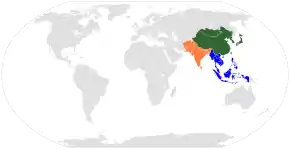

Historically, Asia (excluding Siberia) was regarded as the East, and Europe was regarded as the West. Today, the "West" has generally been divided into three categories: the core area, the marginal area, and the area of Western influence. The core area consists of Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), the European Union (mainly the Western European countries), and Northern America (Canada and the United States). The marginal area consists of Latin America and the Caribbean, the post-Soviet states, the rest of Europe (mainly the Eastern European countries), and South Africa. The area of Western influence consists of countries which have either adopted or influenced by the Western culture, language, political system, religion, way of life or writing system. Some notable examples include Hong Kong, India, Israel, Japan, Macao, the Malay Archipelago, Mongolia, the Pacific Islands, Singapore, most of the sub-Saharan African countries, and Vietnam. Occasionally, even the likes of South Korea, Taiwan, and most of the MENA countries have been included in the area of Western influence.[1]

Used in discussing such studies as management, economics, international relations, and linguistics, the concept is criticized for overlooking regional hybridity.

Divisions

Conceptually, the boundaries are cultural, rather than geographical, as a result of which Australia is typically grouped in the West (despite being geographically in the east), while Islamic nations are, regardless of location, grouped in the East.[2] However, there are a few Muslim-majority regions in Europe which do not fit this dichotomy. The culture line can be particularly difficult to place in regions of cultural diversity such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, whose citizens may themselves identify as East or West depending on ethnic or religious background.[2] Further, residents of different parts of the world perceive the boundaries differently; for example, some European scholars define Russia as East, but most agree that it is the West's second complementary part,[3] and Islamic nations regard it and other predominantly Christian nations as the West.[2] Another unanswered question is whether Siberia (North Asia) is "Eastern" or "Western."

Historical contrast between East and West

During the Middle Ages, the many civilizations present in both East and West were similar in some ways, and irreconcilably different in others. Differences in the social class system were one of the major issues that affected many areas of life when the two societies interacted. The divide between feudalism and the Eastern social system, competing methods of trade and agriculture, and varying stability of governments lead to an ever widening gap between the two ways of life. The West and the Eastern civilizations are not only different because of where they are, but also because of their social class system, their ways of making money, and leadership styles.[4]

The daily life of the common people in the Western and the Eastern Civilizations differed greatly based on how their society was run, and what it was focused on. Two of the major differences between the West and the East were feudalism and manorialism.[5] They both shaped the social hierarchy and the overall life of the common person in the East. The manorial system was set up with a lord at the top who owned a large amount of land. He had serfs and peasants that he employed, the peasants in exchange for the land they got, for working, paid a rent of crop to the lord. This feudal society was every man for himself and did not help in the expansion of a civilization.[6][7]

The social system of the West and East were different. Mongolia rose from nomadic tribes united by Genghis Khan. He conquered much of the surrounding land and created a large empire. They would give the defenders a choice to either join them or die.[8] This brutal mentality was shown when they conquered the vast majority of Asia and some of Europe and the Middle East. One thing that set the Tang dynasty of China apart was their increased social mobility. They had a series of tests that could be taken to better social status. Instead of the high-ranking positions being exclusively for the aristocrats, they were easier for the poor to gain access to. In the West, it was harder to move up or down in the social classes, but in Eastern Civilizations, mobility was possible. In China, it was possible to move up in social status through tests and, in Mongolia it was possible to gain rank in the army through military skill because the society was based on its military prowess.[9]

The West and the Eastern civilizations differed politically because the common people of the East were not always content with their leadership. While the West had many rulers in a short period of time, there was no unrest with the people. Eastern civilizations had rebellions and long gaps between rulers that caused unrest. In England, there was a major war for the throne that lasted for almost a century. During a major war in the 14th and 15th century, England had many struggles for the throne that lead to much bloodshed. France also had problems in their government. Throughout all of this, England was still able to fight the French and almost win in the Hundred Years War. In Eastern civilizations the government was not always stable.[10] In China, one of the deadliest events in human history occurred during the Tang dynasty. The An Lushan Rebellion was very bloody and shows the instability in the Chinese government.[11]

Economically, the West and the Eastern civilizations were drastically different because of how they acquired money. In China, one of the major economic factors was the trade. They were connected to Europe with the Silk Road, this was a series of trade routes from East Asia to Europe. The Silk Road was not only used to trade goods, it was also a place for trading ways of thought or religion. The English employed a special type of feudalism called bastard feudalism.[12] This type of feudalism, prominent in the War of the Roses, was different from regular feudalism because it introduces money into the social hierarchy.[13][14] Nobles could now pay their knights for their service in money instead of giving them land. This strengthened the feudal system because if there was a weak ruler, the strong government of the new nobles would support the people. The British nobles also created Magna carta to reduce the kings power. This monetization of the class system changed how England was ruled and made it very different from the Eastern Civilizations.[15]

Historical concepts

.tif.jpg.webp)

The concept has been used in both "Eastern" and "Western" nations. Japanese sinologist Tachibana Shiraki, in the 1920s, wrote of the need to unify Asia—East Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia but excluding Central Asia and the Middle East—and form a "New East" that might combine culturally in balancing against the West.[16] Japan continued to make much of the concept, known as Pan-Asianism, throughout World War II, in propaganda.[17] In China, it was encapsulated during the Cold War in a 1957 speech by Mao Zedong,[18] who launched a slogan when he said, "This is a war between two worlds. The West Wind cannot prevail over the East Wind; the East Wind is bound to prevail over the West Wind."[19]

To Western writers, in the 1940s, it became bound up with an idea of aggressive, "frustrated nationalism", which was seen as "intrinsically anti- or non-Western"; sociologist Frank Furedi wrote, "The already existing intellectual assessment of European nationalism adapted to the growth of the Third World variety by developing the couplet of mature Western versus immature Eastern nationalism.... This East-West dichotomy became an accepted part of Western political theory."[20]

The 1978 book Orientalism, by Edward Said, was highly influential in further establishing concepts of the East–West dichotomy in the Western world, bringing into college lectures a notion of the East as "characterized by religious sensibilities, familial social orders, and ageless traditions" in contrast to Western "rationality, material and technical dynamism, and individualism."[21]

More recently, the divide has also been posited as an Islamic "East" and an American and European "West."[22][23] Critics note that an Islamic/non-Islamic East–West dichotomy is complicated by the global dissemination of Islamic fundamentalism and by cultural diversity within Islamic nations, moving the argument "beyond that of an East-West dichotomy and into a tripartite situation."[24]

Applications

The East–West dichotomy has been used in studying a range of topics, including management, economics and linguistics. Knowledge Creation and Management (2007) examines it as the difference in organizational learning between Western cultures and the Eastern world.[25] It has been widely used in exploring the period of rapid economic growth that has been termed the "East-Asian miracle" in segments of East Asia, particularly the Asian Tigers, following World War II.[26] Some sociologists, in line with the West as a model of modernity posited by Arnold J. Toynbee, have perceived the economic expansion as a sign of the "Westernization" of the region, but others look for explanation in cultural/racial characteristics of the East, embracing concepts of fixed Eastern cultural identity in a phenomenon described as "New Orientalism".[2][27] Both approaches to the East–West dichotomy have been criticized for failing to take into account the historical hybridity of the regions.[28]

The concept has also been brought to bear on examinations of intercultural communication. Asians are widely described as embracing an "inductive speech pattern" in which a primary point is approached indirectly, but Western societies are said to use "deductive speech" in which speakers immediately establish their point.[29] That is attributed to a higher priority among Asians in harmonious interrelations, but Westerners are said to prioritize direct communication.[30] 2001's Intercultural Communication: A Discourse Approach described the East–West dichotomy linguistically as a "false dichotomy", noting that both Asian and Western speakers use both forms of communication.[31]

Criticism

In addition to difficulties in defining regions and overlooking hybridity, the East–West dichotomy has been criticized for creating an artificial construct of regional unification that allows one voice to claim authority to speak for multitudes. In "The Triumph of the East?", Mark T. Berger speaks to the issue as relates to examination of the "East-Asian miracle":

The historical power of the East-West dichotomy, and the fixed conceptions of culture/race to which it is linked, have increasingly allowed the national elites of the region to speak not only for their 'nations,' but even for Asia and Asians.... There are numerous instances of Western scholars, intent on challenging North American and/or Western hegemony in both material and discursive terms, ending up uncritically privileging the elite narratives of power-holders in Asia as authentic representatives of a particular non-Western nation or social formation (and also contributing to the continued use of the East-West dichotomy).[32]

See also

References

- What We Mean by the West - Foreign Policy Research Institute

- Meštrovic, Stjepan (1994). Balkanization of the West: The Confluence of Postmodernism and Postcommunism. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 0-203-34464-2.

- MacGilchrist, Felicitas. "Metaphorical politics: Is Russia western?". Nation in Formation: Inclusion and Exclusion in Central ….

- François Louis Ganshof (1944). Qu'est-ce que la féodalité. Translated into English by Philip Grierson as Feudalism, with a foreword by F. M. Stenton, 1st ed.: New York and London, 1952; 2nd ed: 1961; 3d ed: 1976.

- Andrew Jones, "The Rise and Fall of the Manorial System: A Critical Comment" The Journal of Economic History 32.4 (December 1972:938–944) p. 938; a comment on D. North and R. Thomas, "The rise and fall of the manorial system: a theoretical model", The Journal of Economic History 31 (December 1971:777–803).

- William Stubbs. The Constitutional History of England. Oxford: 1875.

- G. McMullan and D. Matthews, Reading the medieval in early modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 231.

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [First published 1972]. History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- H. Damico, J. B. Zavadil, D. Fennema, and K. Lenz, Medieval Scholarship: Philosophy and the arts: biographical studies on the formation of a discipline (Taylor & Francis, 1995), p. 80.

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X.

- Livery and Maintenance, Encyclopedia of The Wars of the Roses, ed. John A. Wagner, (ABC-CLIO, 2001), 145.

- "Feudalism", by Elizabeth A. R. Brown. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- "Feudalism?", by Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- "The Problem of Feudalism: An Historiographical Essay", by Robert Harbison, 1996, Western Kentucky University.

- Li, Lincoln (1996). The China factor in Modern Japanese thought: the case of Tachibana Shiraki, 1881–1945. SUNY Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture. SUNY Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0-7914-3039-1.

- Iriye, Akira (2002). Global community: the role of international organizations in the making of the contemporary world. University of California Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-520-23127-9.

- Kau, John K.; Leung (1992). "Notes". The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949–1976: January 1956 – December 1957. Writings of Mao Zedong. 2. M. E. Sharpe. p. 773. ISBN 0-87332-392-0.

- Zedong, Mao (1992). Kau, Michael Y. M.; Leung, John K. (eds.). The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949–1976: January 1956 – December 1957. Writings of Mao Zedong. 2. M.E. Sharpe. p. 775. ISBN 0-87332-392-0.

- Füredi, Frank (1994). Colonial wars and the politics of Third World nationalism. I.B.Tauris. pp. 115–116.

- Barnett, Suzanne Wilson; Van Jay Symons (2000). Asia in the undergraduate curriculum: a case for Asian studies in liberal arts education. East Gate. M.E. Sharpe. p. 99. ISBN 0-7656-0546-5.

- Meštrovic, 63.

- See also Chahuán, Eugenio (2006). "An East-West dichotomy: Islamophobia". In Schenker, Hillel; Ziad, Abu Zayyad (eds.). Islamophobia and anti-Semitism. A Palestine-Israel Journal Book. Markus Wiener Publishers. pp. 25–32. ISBN 1-55876-403-8.

- Khatib, Lina (2006). Filming the modern Middle East: politics in the cinemas of Hollywood and the Arab world. Library of Modern Middle East Studies, Library of International Relations. 57. I.B. Tauris. pp. 166–167, 173. ISBN 1-84511-191-5.

- Ichijō, Kazuo; Ikujirō Nonaka (2007). Knowledge creation and management: new challenges for managers. Oxford University Press US. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-19-515962-2.

- Norberg, Johan (2003). In defense of global capitalism. Cato Institute. p. 99. ISBN 1-930865-46-5.

- Berger, Mark T. (1997). "The triumph of the East? The East-Asian Miracle and post-Cold War capitalism". In Borer, Douglas A. (ed.). The rise of East Asia: critical visions of the Pacific century. Routledge. pp. 260–261, 266. ISBN 0-415-16168-1.

- Berger, 275.

- Cheng, Winnie (2003). Intercultural conversation. Pragmatics & Beyond. 118. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 51. ISBN 90-272-5360-9.

- Cheng, 53.

- Scollon, Ronald (2001). Intercultural communication: a discourse approach. Language in Society. 21 (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0-631-22418-1.

- Berger, 276

Further reading

Balancing the East, Upgrading the West; U.S. Grand Strategy in an Age of Upheaval by Zbigniew Brzezinski January/February 2012 Foreign Affairs

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: East–West dichotomy |