East Asia

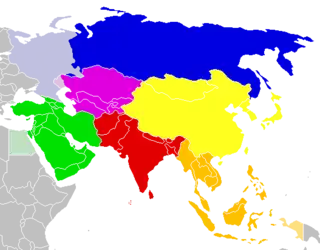

East Asia or Northeast Asia is the northeastern subregion of Asia, which can be defined in both geographical or ethno-cultural terms.[3][4] Generally, the modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan.[5] The East Asian states of China, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan are all unrecognized by at least one other East Asian state due to severe ongoing political tensions in the region, specifically the division of Korea and the political status of Taiwan. Hong Kong and Macau, two small coastal quasi-dependent territories located in the south of China, are officially highly autonomous but are under de jure Chinese sovereignty. North Asia borders East Asia's north, Southeast Asia the south, South Asia the southwest and Central Asia the west. To the east is the Pacific Ocean and to the southeast is Micronesia (a Pacific Ocean island group, classified as part of Oceania).

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Area | 11,840,000 km2 (4,570,000 sq mi) (3rd) |

|---|---|

| Population | 1.6 billion (2020; 4th) |

| Population density | 141.9/km2 (54.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | $23 trillion (2020 est.)[1] |

| Demonym | East Asian |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | |

| Languages | Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Tibetan, Others |

| Time zones | UTC+7, UTC+8 & UTC+9 |

| Largest cities | List of urban areas:[2] |

| UN M49 code | 030 – Eastern Asia142 – Asia001 – World |

| East Asia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 东亚/东亚细亚 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 東亞/東亞細亞 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཨེ་ཤ་ཡ་ཤར་མ་ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 동아시아/동아세아/동아 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 東아시아/東亞細亞/東亞 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Зүүн Ази ᠵᠡᠭᠦᠨ ᠠᠽᠢ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ひがしアジア/とうあ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 東亞細亞/東亞 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 東亜細亜(東アジア)/東亜 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | شەرقىي ئاسىي | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

East Asia, especially Chinese civilization, is regarded as one of the earliest cradles of civilization. Other ancient civilizations in East Asia that still exist as independent countries in the present day include the Japanese, Korean and Mongolian civilizations. Various other civilizations existed in East Asia in the past but have since been absorbed into neighbouring civilizations in the present day, such as Tibet, Baiyue, Manchuria and Ryukyu, among many others. Taiwan has a relatively young history in the region after the prehistoric era; originally, it was a major site of Austronesian civilization prior to colonization by European colonial powers and China from the 17th century onward. For thousands of years, China was the leading civilization in the region, exerting influence on its neighbors.[6][7][8] Historically, societies in East Asia have fallen within the Chinese sphere of influence, and East Asian vocabulary and scripts are often derived from Classical Chinese and Chinese script. The Chinese calendar serves as the root from which many other East Asian calendars are derived. Major religions in East Asia include Buddhism (mostly Mahayana[9]), Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism, Taoism, Ancestral worship, and Chinese folk religion in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, Shintoism in Japan, and Christianity, and Sindoism in Korea.[10][11][12] Tengerism and Tibetan Buddhism are prevalent among Mongols and Tibetans while other religions such as Shamanism are widespread among the indigenous populations of northeastern China such as the Manchus.[13][14][15] Major languages in East Asia include Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Major ethnic groups of East Asia include the Han (mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan), Yamato (Japan) and Koreans (North Korea, South Korea). Mongols, although not as populous as the previous three ethnic groups, constitute the majority of Mongolia's population. There are 76 officially-recognized minority or indigenous ethnic groups in East Asia; 55 native to mainland China (including Hui, Manchus, Chinese Mongols, Tibetans, Uyghurs and Zhuang in the frontier regions), 16 native to the island of Taiwan (collectively known as Taiwanese indigenous peoples), one native to the major Japanese island of Hokkaido (the Ainu) and four native to Mongolia (Turkic peoples). Ryukyuan people are an unrecognised ethnic group indigenous to the Ryukyu Islands in southern Japan, which stretch from Kyushu Island (Japan) to Taiwan. There are also several unrecognised indigenous ethnic groups in mainland China and Taiwan.

East Asians comprise around 1.7 billion people, making up about 38% of the population in Continental Asia and 20.5% of the global population.[16][17][18] The region is home to major world metropolises such as Beijing, Hong Kong, Seoul, Shanghai, Taipei, and Tokyo. Although the coastal and riparian areas of the region form one of the world's most populated places, the population in Mongolia and Western China, both landlocked areas, is sparsely distributed, with Mongolia having the lowest population density of a sovereign state. The overall population density of the region is 133 inhabitants per square kilometre (340/sq mi), about three times the world average of 45/km2 (120/sq mi).

East Asia has some of the world's largest and most prosperous economies: Mainland China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.[19]

History

China was the first region settled in East Asia and was undoubtedly the core of East Asian civilization from where other parts of East Asia were formed.[20] The various other regions in East Asia were selective in the Chinese influences they adopted into their local customs. Historian Ping-ti Ho famously labeled Chinese civilization as the "Cradle of Eastern Civilization", in parallel with the "Cradle of Western Civilization" along the Fertile Crescent encompassing Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.[21]

Chinese civilization existed for about 1500 years before other East Asian civilizations emerged into history, Imperial China would exert much of its cultural, economic, technological, and political muscle onto its neighbors.[22][23][24][25] Succeeding Chinese dynasties exerted enormous influence across East Asia culturally, economically, politically and militarily for over two millennia.[25][26][27] The Imperial Chinese tributary system shaped much of East Asia's history for over two millennia due to Imperial China's economic and cultural influence over the region, and thus played a huge role in the history of East Asia in particular.[28][29][24] Imperial China's cultural preeminence not only led the country to become East Asia's first literate nation in the entire region, it also supplied Japan and Korea with Chinese loanwords and linguistic influences rooted in their writing systems.[30]

Under Emperor Wu of Han, the Han dynasty made China the regional power in East Asia, projecting much of its imperial power on its neighbors.[25][31] Han China hosted the largest unified population in East Asia, the most literate and urbanized as well as being the most economically developed, as well as the most technologically and culturally advanced civilization in the region at the time.[32][33] Cultural and religious interaction between the Chinese and other regional East Asian dynasties and kingdoms occurred. China's impact and influence on Korea began with the Han dynasty's northeastern expansion in 108 BC when the Han Chinese conquered the northern part of the Korean peninsula and established a province called Lelang. Chinese influence would soon take root in Korea through the inclusion of the Chinese writing system, monetary system, rice culture, and Confucian political institutions.[34] Jomon society in ancient Japan incorporated wet-rice cultivation and metallurgy through its contact with Korea. Starting from the fourth century AD, Japan incorporated the Chinese writing system which evolved into Kanji by the fifth century AD and has become a significant part of the Japanese writing system.[35] Utilizing the Chinese writing system allowed the Japanese to conduct their daily activities, maintain historical records and give form to various ideas, thoughts, and philosophies.[36] During the Tang dynasty, China exerted its greatest influence on East Asia as various aspects of Chinese culture spread to Japan and Korea.[37][38] As full-fledged medieval East Asian states were established, Korea by the fourth century AD and Japan by the seventh century AD, Japan and Korea actively began to incorporate Chinese influences such as Confucianism, the use of written Han characters, Chinese style architecture, state institutions, political philosophies, religion, urban planning, and various scientific and technological methods into their culture and society through direct contacts with Tang China and succeeding Chinese dynasties.[39][40][41] Drawing inspiration from the Tang political system, Prince Naka no oe launched the Taika Reform in 645 AD where he radically transformed Japan's political bureaucracy into a more into a more centralized bureaucratic empire.[42] The Japanese also adopted Mahayana Buddhism, Chinese style architecture, and the imperial court's rituals and ceremonies, including the orchestral music and state dances had Tang influences. Written Chinese gained prestige and aspects of Tang culture such as poetry, calligraphy, and landscape painting became widespread.[43] During the Nara period, Japan began to aggressively import Chinese culture and styles of government which included Confucian protocol that served as a foundation for Japanese culture as well as political and social philosophy.[44][45] The Japanese also created laws adopted from the Chinese legal system that was used to govern in addition to the kimono, which was inspired from the Chinese robe (hanfu) during the eighth century AD.[46] For many centuries, most notably from the 7th to the 14th centuries, China stood as East Asia's most advanced civilization and foremost military and economic power exerting its influence as the transmission of advanced Chinese cultural practices and ways of thinking greatly shaped the region up until the nineteenth century.[47][48][49][50]

As East Asia's connections with Europe and the Western world strengthened during the late nineteenth century, China's power began to decline.[22][51] By the mid-nineteenth century, the weakening Qing dynasty became fraught with political corruption, obstacles and stagnation that was incapable of rejuvenating itself as a world power in contrast to the industrializing Imperial European colonial powers and a rapidly modernizing Japan.[52][53] The U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry would open Japan to Western ways, and the country would expand in earnest after the 1860s.[54][55][56] Around the same time, Japan with its rush to modernity transformed itself from an isolated feudal samurai state into East Asia's first industrialized nation in the modern era.[57][58][55] The modern and militarily powerful Japan would galvanize its position in the Orient as East Asia's greatest power with a global mission poised to advance to lead the entire world.[57][59] By the early 1900s, the Japanese empire succeeded in asserting itself as East Asia's most dominant power.[59] With its newly found international status, Japan would begin to challenge the European colonial powers and inextricably took on a more active geopolitical position in East Asia and world affairs at large.[60] Flexing its nascent political and military might, Japan soundly defeated the stagnant Qing dynasty during the First Sino-Japanese War as well as vanquishing imperial rival Russia in 1905; the first major military victory in the modern era of an East Asian power over a European one.[61][62][63][64][54] Its hegemony was the heart of an empire that would include Taiwan and Korea.[57] During World War II, Japanese expansionism with its imperialist aspirations through the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere would incorporate Korea, Taiwan, much of eastern China and Manchuria, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia under its control establishing itself as a maritime colonial power in East Asia.[65] After a century of exploitation by the European and Japanese colonialists, post-colonial East Asia saw the defeat and occupation of Japan by the victorious Allies as well as the division of China and Korea during the Cold War. The Korean peninsula became independent but then it was divided into two rival states, while Taiwan became the main territory of de facto state Republic of China after the latter lost Mainland China to the People's Republic of China in the Chinese Civil War. During the latter half of the twentieth century, the region would see the post war economic miracle of Japan, which ushered in three decades of unprecedented growth, only to experience an economic slowdown during the 1990s, but nonetheless Japan continues to remain a global economic power. East Asia would also see the economic rise of South Korea and Taiwan, and the integration of Mainland China into the global economy through its entry in the World Trade Organization while enhancing its emerging international status as a potential world power.[5][66][67] Although there have been no wars in East Asia for decades, the stability of the region remains fragile because of North Korea's nuclear program.

Definitions

In common usage, the term "East Asia" typically refers to a region including Greater China, Japan, and Korea.[68][69][70][71][16][72][73][74][75][76][67]

China, Japan, and Korea represent the three core countries and civilizations of traditional East Asia - as they once shared a common written language, culture, as well as sharing Confucian philosophical tenets and the Confucian societal value system once instituted by Imperial China.[77][78][79][80][81] Other usages define Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Japan, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan as countries that constitute East Asia based on their geographic proximity as well as historical and modern cultural and economic ties, particularly with Japan and Korea having strong cultural influences that originated from China.[77][81][82][83][84][85] Some scholars include Vietnam as part of East Asia as it has been considered part of the greater Chinese sphere of influence. Though Confucianism continues to play an important role in Vietnamese culture, Chinese characters are no longer used in its written language and many scholarly organizations classify Vietnam as a Southeast Asian country.[86][87][88] Mongolia is geographically north of Mainland China yet Confucianism and the Chinese writing system and culture had limited impact on Mongolian society. Thus, Mongolia is sometimes grouped with Central Asian countries such as Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan.[86][87] Xinjiang (East Turkestan) and Tibet are sometimes seen as part of Central Asia.[89][90][91]

Broader and looser definitions by international organizations such as the World Bank refer to the "three major Northeast Asian economies, i.e. Mainland China, Japan, and South Korea", as well as Mongolia, North Korea, the Russian Far East and Siberia.[92] The Council on Foreign Relations includes the Russia Far East, Mongolia, and Nepal.[93] The World Bank also acknowledges the roles of sub-national or de facto states, such as Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. The Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia defines the region as "China, Japan, the Koreas, Nepal, Mongolia, and eastern regions of the Russian Federation".[94]

The UNSD definition of East Asia is based on statistical convenience,[95] but also other common definitions of East Asia contain the Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan.[3][96]

Alternative definitions

In business and economics contexts, "East Asia" is can also be used to refer to a wider geographical area covering ten Southeast Asian countries in ASEAN, Greater China, Japan and Korea. However, in this context, the term "Far East" was also previously used by the Europeans to cover ASEAN countries as well as the countries in East Asia. However, being a Eurocentric term, Far East describes the region's geographical position in relation to Europe rather than its location within Asia, and has been considered acharic. Alternatively, the term "Asia-Pacific Region" is often used instead in describing both East and Southeast Asia together, as well as Oceania.[88]

Observers preferring a broader definition of "East Asia" often use the term Northeast Asia to refer to China, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan, with Southeast Asia covering the ten ASEAN countries. This usage, which is seen in economic and diplomatic discussions, is at odds with the historical meanings of both "East Asia" and "Northeast Asia".[97][98][99] The Council on Foreign Relations of the United States defines Northeast Asia as Japan and Korea, but excluding mainland China and the island of Taiwan.[93]

Economy

| Customs territory | GDP nominal billions of USD (2020)[100] |

GDP nominal per capita USD (2020)[100] |

GDP PPP billions of USD (2020)[100] |

GDP PPP per capita USD (2020)[100] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15,222.155 | 10,839.435 | 24,162.435 | 17,205.654 | |

| 341.319 | 45,175.727 | 439.459 | 58,165.200 | |

| 26.348 | 38,769.201 | 40.049 | 58,930.534 | |

| 4,910.580 | 39,047.860 | 5,236.138 | 41,636.628 | |

| 13.385 | 3,989.927 | 41.125 | 12,259.059 | |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 1,586.786 | 30,644.427 | 2,293.475 | 44,292.194 | |

| 635.547 | 26,910.229 | 1,275.805 | 54,019.882 |

Territorial and regional data

Etymology

| Flag | Common Name | Official Name | ISO 3166 Country Codes[103] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exonym | Endonym | Exonym | Endonym | ISO Short Name | Alpha-2 Code | Alpha-3 Code | Numeric | |

| China | 中国 | People's Republic of China | 中华人民共和国 | China | CN | CHN | 156 | |

| Hong Kong | 香港 | Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China | 中華人民共和國香港特別行政區 | Hong Kong | HK | HKG | 344 | |

| Macau | 澳門 | Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China | 中華人民共和國澳門特別行政區 | Macao | MO | MAC | 446 | |

| Japan | 日本 | Japan | 日本国 | Japan | JP | JPN | 392 | |

| Mongolia | Монгол улс / ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | Mongolia | Монгол Улс(ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ) | Mongolia | MN | MNG | 496 | |

| North Korea | 조선 | Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 조선민주주의인민공화국 | Korea (the Democratic People's Republic of) | KP | PRK | 408 | |

| South Korea | 한국 | Republic of Korea | 대한민국 | Korea (the Republic of) | KR | KOR | 410 | |

| Taiwan[104] | 臺灣 / 台灣 | Republic of China | 中華民國 | Taiwan (Province of China)[105] | TW | TWN | 158 | |

Demographics

| State/Territory | Area km2 | Population[106][107] (2018) |

Population density per km2 |

HDI[108] | Capital/Administrative Center |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9,640,011[lower-alpha 2] | 1,427,647,786[lower-alpha 3] | 138 | 0.752 | Beijing | |

| 1,104 | 7,371,730 | 6,390 | 0.933 | Hong Kong | |

| 30 | 631,636 | 18,662 | 0.909 | Macao | |

| 377,930 | 127,202,192 | 337 | 0.909 | Tokyo | |

| 1,564,100 | 3,170,216 | 2 | 0.741 | Ulaanbaatar | |

| 120,538 | 25,549,604 | 198 | 0.733 | Pyongyang[109] | |

| 100,210 | 51,171,706 | 500 | 0.903 | Seoul | |

| 36,197 | 23,726,460 | 639 | 0.907 | Taipei[110] |

Ethnic groups

| Ethnicity | Native name | Population | Language(s) | Writing system(s) | Major states/territories* | Traditional attire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han/Chinese | 漢族 or 汉族 | 1,268,000,000 | Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghainese, Hokkien, Hakka, Gan, Hsiang, etc.) | Simplified Han characters, Traditional Han characters |  | |

| Yamato/Japanese | 大和民族 | 125,117,000[111] | Japanese | Han characters (Kanji), Katakana, Hiragana |  | |

| Korean | 조선족 (朝鮮族) 한민족 (韓民族) |

79,432,225 | Korean | Hangul, Han characters (Hanja) | .jpg.webp) | |

| Bai | 白族 | 1,858,063 | Bai, Southwestern Mandarin | Simplified Han characters, Latin script |  | |

| Hui | 回族 | 10,586,087 | Northwestern Mandarin, other Chinese Dialects, Huihui language, etc. | Simplified Han characters[lower-alpha 4] |  | |

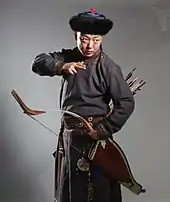

| Mongols | 蒙古族/Монголчууд/ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯᠴᠤᠳ Монгол/ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ |

8,942,528 | Mongolian | Mongol script, Cyrillic script |  | |

| Zhuang | 壮族/Bouxcuengh | 18,000,000 | Zhuang, Southwestern Mandarin, etc. | Simplified Han characters, Latin script |  | |

| Uyghurs | 维吾尔族/ئۇيغۇر | 15,000,000+[112] | Uighur | Arabic alphabet, Cyrillic script |  | |

| Manchus | 满族/ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ | 10,422,873 | Northeastern Mandarin, Manchu language | Simplified Han characters, Mongol script |  | |

| Hmong/Miao | 苗族/Ghaob Xongb/Hmub/Mongb | 9,426,007 | Hmong/Miao, Southwestern Mandarin | Latin script, Simplified Han characters |  | |

| Tibetans | 藏族/བོད་པ་ | 6,500,000 | Tibetan, Rgyal Rong, Rgu, etc. | Tibetan script |  | |

| Yi | 彝族/ꆈꌠ | 8,714,393 | Various Loloish, Southwestern Mandarin | Yi script, Simplified Han characters |  | |

| Tujia | 土家族 | 8,353,912 | Northern Tujia, Southern Tujia | Simplified Han characters |  | |

| Kam | 侗族/Gaeml | 2,879,974 | Gaeml | Simplified Han characters, Latin script |  | |

| Tu | 土族/Monguor | 289,565 | Tu, Northwestern Mandarin | Simplified Han characters |  | |

| Daur | 达斡尔族/ᠳᠠᠭᠤᠷ | 131,992 | Daur, Northeastern Mandarin | Mongol script, Simplified Han characters |  | |

| Indigenous Taiwanese Peoples | 阿美族/Pangcah, etc. | 533,600 | Austronesian languages (Amis, Yami), etc. | Latin script, Traditional Han characters |  | |

| Ryukyuan | 琉球民族(沖縄人) | 1,900,000 | Japanese Ryukyuan |

Han characters (Kanji), Katakana, Hiragana |  | |

| Ainu | アイヌ | 200,000 | Japanese Ainu[113] |

Han characters (Kanji), Katakana, Hiragana |  |

- Note: The order of states/territories follows the population ranking of each ethnicity, within East Asia only.

East Asian culture

Overview

The culture of East Asia has largely been influenced by China, as it was the civilization that had the most dominant influence in the region throughout the ages that ultimately laid the foundation for East Asian civilization.[114] The vast knowledge and ingenuity of Chinese civilization and the classics of Chinese literature and culture were seen as the foundations for a civilized life in East Asia. Imperial China served as a vehicle through which the adoption of Confucian ethical philosophy, Chinese calendar system, political and legal systems, architectural style, diet, terminology, institutions, religious beliefs, imperial examinations that emphasized a knowledge of Chinese classics, political philosophy and cultural value systems, as well as historically sharing a common writing system reflected in the histories of Japan and Korea.[115][25][116][117][118][119][120][121][81] The Imperial Chinese tributary system was the bedrock of network of trade and foreign relations between China and its East Asian tributaries, which helped to shape much of East Asian affairs during the ancient and medieval eras. Through the tributary system, the various dynasties of Imperial China facilitated frequent economic and cultural exchange that influenced the cultures of Japan and Korea and drew them into a Chinese international order.[122][123] The Imperial Chinese tributary system shaped much of East Asia's foreign policy and trade for over two millennia due to Imperial China's economic and cultural dominance over the region, and thus played a huge role in the history of East Asia in particular.[29][123] The relationship between China and its cultural influence on East Asia has been compared to the historical influence of Greco-Roman civilization on Europe and the Western World.[119][117][123][115]

Religions

| Religion | Native name | Creator/Current Leader | Founded Time | Main Denomination | Major book | Type | Est. Followers | Ethnic groups | States/territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese folk religion | 中国民间信仰 | Spontaneous formation | 5000 years from now | Salvationist, Wuism, Nuo | Chinese classics, Huangdi Sijing, precious scrolls, etc. | Prehistoric,pantheism,and polytheism | ~900,000,000[124][125] | Han, Hmong, Qiang, Tujia (worship of the same ancestor-gods) | |

| Taoism | 道教 | Zhang Daoling, was consider the founder of Taoism by Taoists. He founded Zhengyi, the earlist denomination of Taoism. Zhang Daoling reformed the Chinese folk religion from Szechuan, into a real, organised, and regulated religion, in 125A.D.. Wang Chongyang founded the Quanzhen Denomination. Tale says Wang Chongyang met two Gods, Lü Dongbin and Han Zhongli, during Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in 1159. He then get started to study Taoism himself. Three years later, he finished his studying, and founded Quanzhen. The new leader of Zhengyi need to be the son or paternal nephew of the previous leader, confirmed by the court of Zhengyi, in Mount Longhu, Jiangxi. Also beginning from the Song Dynasty, the leaders of Zhengyi get started to be confirmed and titled by the Emperor of China. In 1949, the 63th leader, Zhang Enfu, fled to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Kuomintang, died in 1969 in Taipei. The Kuomintang Authority titled his cousin Zhang Yuanxian as the 64th leader, while the Court of Zhengyi back in Jiangxi argued that the oracle already foreseen the leadership will end at the 63th generation. Zhang Yuanxian died in 2008, only left a daughter as heir. Meanwhile, the Kuomintang Authority didn't confirmed the next leader. On the other hand, in Mainland China, Zhang Enfu's second daughter's son, Lu Jintao, changes his surname to Zhang, and get in charge of the Court of Zhengyi currently. For the leader of Quanzhen, the last (18th) leader (1335-1362) was Wanyan Deming, titled by the Emperor of Yuan Dynasty. Wanyan Deming was a Jurchen Taoist, the Wanyan family was the imperial house of Jin Dynasty. There is no official leader of Quanzhen after Wanyan Deming anymore. | 125 A.D. Eastern Han dynasty | Zhengyi, Quanzhen | Tao Te Ching | Pantheism, polytheism | ~20,000,000[125] | Han, Zhuang, Hmong, Yao, Qiang, Tujia | |

| East Asian Buddhism/Chinese Buddhism | 漢傳佛教 or 汉传佛教 | The Emperor of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Liu Zhuang, made a dream about the Buddha occasionally, then sent people to the Western Regions to Introduce Buddhism to the Capital, Chang'an, in 67 A.D. In 384 A.D., during the Eastern Jin dynasty, Indian Mālānanda introduced the Chinese Buddhism to Baekje. In 552 A.D., King Seong of Baekje offered Buddhism to the Emperor Kinmei of Japan. | 67 A.D. Eastern Han dynasty | Mahayana | Diamond Sutra | Non-God, Dualism. | ~300,000,000 | Han, Korean, Yamato | |

| Tibetan Buddhism | 藏传佛教/བོད་བརྒྱུད་ནང་བསྟན། | Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, Prince of the Ancient Xang Xung Kingdom. | 1800 years ago | Mahayana, Bon | Anuttarayoga Tantra | Non-God | ~10,000,000 | Tibetans, Manchus, Mongols | |

| Shamanism[lower-alpha 6] | 萨满教 or Бөө мөргөл | Spontaneous formation | Prehistoric period | N/A | Prehistoric, polytheism, and pantheism | N/A | Manchus, Mongols, Oroqen | ||

| Shintoism | 神道 | Spontaneous formation | Jōmon period | Shinto sects | Kojiki, Nihon Shoki | Prehistoric,pantheism,and polytheism | N/A | Yamato | |

| Shindo/Muism | 신도 or 무교 | Spontaneous formation | 900 years ago | Shindo sects | N/A | Prehistoric,pantheism,and polytheism | N/A | Korean | |

| Ryukyuan religion | 琉球神道 or ニライカナイ信仰 | Spontaneous formation | N/A | N/A | N/A | Prehistoric,pantheism,and polytheism | N/A | Ryukyuan |

Festivals

| Festival | Native Name | Other name | Calendar | Date | Gregorian date | Activity | Religious practices | Food | Major ethnicities | Major states/territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lunar New Year | 農曆新年/农历新年 or 春節/春节 | Spring Festival | Chinese | Month 1 Day 1 | 21 Jan–20 Feb | Family Reunion, Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping, Fireworks | Worship the King of Gods | Jiaozi | Han, Manchus etc. | |

| Korean New Year | 설날 or 설 | Seollal | Korean | Month 1 Day 1 | 21 Jan–20 Feb | Ancestors Worship, Family Reunion, Tomb Sweeping | N/A | Tteokguk | Korean | |

| Losar or Tsagaan Sar | 藏历新年/ལོ་གསར་ or 查干萨日/Цагаан сар | White Moon | Tibetan, Mongolian | Month 1 Day 1 | 25 Jan – 2 Mar | Family Reunion, Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping, Fireworks | N/A | Chhaang or Buuz | Tibetans, Mongols, Tu etc. | |

| New Year | 元旦 | Yuan Dan | Gregorian | 1 Jan | 1 Jan | Fireworks | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Lantern Festival | 元宵節 or 元宵节 | Upper Yuan Festival (上元节) | Chinese | Month 1 Day 15 | 4 Feb – 6 Mar | Lanterns Expo, Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping | Birthdate of the God of Sky-officer | Yuanxiao | Han | |

| Daeboreum | 대보름 or 정월 대보름 | Great Full Moon | Korean | Month 1 Day 15 | 4 Feb – 6 Mar | Greeting of the moon, kite-flying, Jwibulnori, eating nuts (Bureom) | Bonfires (daljip taeugi) | Ogok-bap, namul, nuts | Korean | |

| Hanshi Festival | 寒食節 or 寒食节 | Cold Food Festival | Solar term | Traditionally, on the 105th day after the Winter solstice. Revised to 1 day before the Qingming Festival by Johann Adam Schall von Bell (Chinese: 汤若望) during the Qing dynasty. | April 3–5 | Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping, No cooking hot meal/setting fire, Cold food only. Cuju, etc. (People used to mix this one with the Qingming Festival due to their close dates) | In Memory of a loyal Ancient named Jie Zhitui (Chinese: 介子推), ordered by the Monarch of the Jin (Chinese state), Duke Wen of Jin (Chinese: 重耳) | Cold Food, e.g. Qingtuan | Han, Korean, Mongols | |

| Qingming Festival | 清明節 or 清明节 | Tomb Sweeping Day | Solar term | 15th day after the Vernal Equinox. Just 1 day after the Hanshi Festival, but in much higher repute. | April 4-6th | Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping, Excursion, Planting trees, Flying kites, Tug of war, Cuju, etc. (Almost the same with the Hanshi Festival's, due to their close dates) | Burning Hell money for deceased family members. Planting willow brances to keep ghosts away from houses. | Boiled eggs | Han, Korean, Mongols | |

| Dragon Boat Festival | 端午節 or 端午节 or 단오 | Duanwu Festival / Dano (Surit-nal) | Chinese / Korean | Month 5 Day 5 | Driving poisons & plague away. (China - Dragon Boat Race, Wearing colored lines, Hanging felon herb on the front door.) / (Korea - Washing hair with iris water, ssireum) | Worship various Gods | Zongzi / Surichwitteok (rice cake with herbs) | Han, Korean, Yamato | ||

| Ghost Festival | 中元節 or 中元节 or 백중 | Mid Yuan Festival | Chinese | Month 7 Day 15 | Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping | Birthdate of the God of Earth-officer | Han, Korean, Yamato | |||

| Mid-Autumn Festival | 中秋節 or 中秋节 | 中秋祭 | Chinese | Month 8 Day 15 | Family Reunion, Enjoying Moon view | Worship the Moon Goddess | Mooncake | Han | ||

| Chuseok | 추석 or 한가위 | Hangawi | Korean | Month 8 Day 15 | Family Reunion, Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping, Enjoying Moon view | N/A | Songpyeon, Torantang (Taro soup) | Korean | ||

| Double Ninth Festival | 重陽節 or 重阳节 | Double Positive Festival | Chinese | Month 9 Day 09 | Climbing Mountain, Taking care of elderly, Wearing Cornus. | Worship various Gods | Han, Korean, Yamato | |||

| Lower Yuan Festival | 下元節 or 下元节 | N/A | Chinese | Month 10 Day 15 | Ancestors Worship, Tomb Sweeping | Birthdate of the God of Water-officer | Ciba | Han | ||

| Dongzhi Festival | 冬至 or 동지 | N/A | Gregorian | Between Dec 21 and Dec 23 | Between Dec 21 and Dec 23 | Ancestors Worship, Rites to dispel bad spirits | N/A | Tangyuan, Patjuk | Han, Korean | |

| Small New Year | 小年 | Jizao (祭灶) | Chinese | Month 12 Day 23 | Cleaning Houses | Worship the God of Hearth | tanggua | Han, Mongols | ||

| International Labor Day | N/A | N/A | Gregorian | 1 May | 1 May | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| International Women's Day | N/A | N/A | Gregorian | 8 Mar | 8 Mar | Taking care of women | N/A | N/A | N/A | All |

*Japan switched the date to the Gregorian calendar after the Meiji Restoration.

*Not always on that Gregorian date, sometimes April 4.

Collaboration

East Asian Youth Games

Formerly the East Asian Games, it is a multi-sport event organised by the East Asian Games Association (EAGA) and held every four years since 2019 among athletes from East Asian countries and territories of the Olympic Council of Asia (OCA), as well as the Pacific island of Guam, which is a member of the Oceania National Olympic Committees.

It is one of five Regional Games of the OCA. The others are the Central Asian Games, the Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games), the South Asian Games and the West Asian Games.

Free trade agreements

| Name of agreement | Parties | Leaders at the time | Negotiation begins | Signing date | Starting time | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China–South Korea FTA | Xi Jinping, Park Geun-hye | May, 2012 | Jun 01, 2015 | Dec 30, 2015 | Enforced | |

| China–Japan–South Korea FTA | Xi Jinping, Shinzō Abe, Park Geun-hye | Mar 26, 2013 | N/A | N/A | 10 round negotiation | |

| Japan-Mongolia EPA | Shinzō Abe, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj | - | Feb 10, 2015 | - | Enforced | |

| China-Mongolia FTA | Xi Jinping, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj | N/A | N/A | N/A | Officially proposed | |

| China-HK CEPA | Jiang Zemin, Tung Chee-hwa | - | Jun 29, 2003 | - | Enforced | |

| China-Macau CEPA | Jiang Zemin, Edmund Ho Hau-wah | - | Oct 18, 2003 | - | Enforced | |

| Hong Kong-Macau CEPA | Carrie Lam, Fernando Chui | Oct 09, 2015 | N/A | N/A | Negotiating | |

| ECFA | Hu Jintao, Ma Ying-jeou | Jan 26, 2010 | Jun 29, 2010 | Aug 17, 2010 | Enforced | |

| CSSTA (Based on ECFA) | Xi Jinping, Ma Ying-jeou | Mar, 2011 | Jun 21, 2013 | N/A | Abolished | |

| CSGTA (Based on ECFA) | Hu Jintao, Ma Ying-jeou | Feb 22, 2011 | N/A | N/A | Suspended |

Military alliances

| Name | Abbr. | Parties within the region |

|---|---|---|

| Shanghai Cooperation Organisation | SCO | |

| General Security of Military Information Agreement | GSOMIA | |

| Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty | - | |

| Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan | - | |

| Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea | - | |

| Taiwan Relations Act (Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty before 1980) | TRA (SAMDT) | |

| Major non-NATO ally (Global Partners of NATO) | - |

Major cities

.jpg.webp) Beijing is the capital of the People's Republic of China and the largest metropolis in northern China.

Beijing is the capital of the People's Republic of China and the largest metropolis in northern China. Guangzhou is one of the most important cities in southern China. It has a history of over 2,200 years and was a major terminus of the maritime Silk Road and continues to serve as a major port and transportation hub today.

Guangzhou is one of the most important cities in southern China. It has a history of over 2,200 years and was a major terminus of the maritime Silk Road and continues to serve as a major port and transportation hub today. Hong Kong is one of the world's leading global financial centres and is known as a cosmopolitan metropolis.

Hong Kong is one of the world's leading global financial centres and is known as a cosmopolitan metropolis..jpg.webp) Kaohsiung is the harbor capital and largest city in southern Taiwan.

Kaohsiung is the harbor capital and largest city in southern Taiwan. Kyoto was the imperial capital of Japan for eleven centuries.

Kyoto was the imperial capital of Japan for eleven centuries. Osaka is the second largest metropolitan area in Japan.

Osaka is the second largest metropolitan area in Japan..jpg.webp) Pyongyang is the capital of North Korea, and is a significant metropolis on the Korean Peninsula.

Pyongyang is the capital of North Korea, and is a significant metropolis on the Korean Peninsula. Shanghai is the largest city in China and one of the largest in the world, and is a global financial centre and transport hub with the world's busiest container port.

Shanghai is the largest city in China and one of the largest in the world, and is a global financial centre and transport hub with the world's busiest container port..jpg.webp) Seoul is the capital of South Korea, one of the largest cities in the world and a leading global technology hub.

Seoul is the capital of South Korea, one of the largest cities in the world and a leading global technology hub. Taipei is the de facto capital of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and anchors a major high-tech industrial area in Taiwan.

Taipei is the de facto capital of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and anchors a major high-tech industrial area in Taiwan..jpg.webp) Tokyo is the capital of Japan and one of the largest cities in the world, both in metropolitan population and economy.

Tokyo is the capital of Japan and one of the largest cities in the world, both in metropolitan population and economy. Ulaanbaatar is the capital of Mongolia with a population of 1 million as of 2008.

Ulaanbaatar is the capital of Mongolia with a population of 1 million as of 2008.

See also

Notes

- listed as "Taiwan Province of China" by the IMF

- Includes all area which under PRC's government control (excluding "South Tibet" and disputed islands).

- A note by the United Nations: "For statistical purposes, the data for China do not include Hong Kong and Macao, Special Administrative Regions (SAR) of China, and Taiwan Province of China."

- The Hui people also use the Arabic alphabet in the religious field.

- The Khotons also in

.

. - almost Manchu, Mongolian

References

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund.

- "Demographia.com" (PDF).

- "East Asia". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

the countries and regions of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Mongolia, South Korea, North Korea and Japan.

- Miller, David Y. (2007). Modern East Asia: An Introductory History. Routledge. pp. xxi–xxiv. ISBN 978-0765618221.

- Kort, Michael (2005). The Handbook Of East Asia. Lerner Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 978-0761326724.

- Zaharna, R.S.; Arsenault, Amelia; Fisher, Ali (2013). Relational, Networked and Collaborative Approaches to Public Diplomacy: The Connective Mindshift (1st ed.). Routledge (published 2013-05-01). p. 93. ISBN 978-0415636070.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1107544895.

- Szonyi, Michael (2017). A Companion to Chinese History. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 90. ISBN 978-1118624609.

- Selin, Helaine (2010). Nature Across Cultures: Views of Nature and the Environment in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. p. 350. ISBN 978-9048162710.

- Salkind, Neil J. (2008). Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology. Sage Publications. p. 56. ISBN 978-1412916882.

- Kim, Chongho (2003). Korean Shamanism: The Cultural Paradox. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754631859.

- Andreas Anangguru Yewangoe, "Theologia crucis in Asia", 1987 Rodopi

- Heissig, Walther (2000). The Religions of Mongolia. Translated by Samuel, Geoffrey. Kegan Paul International. p. 46. ISBN 9780710306852.

- Elliott (2001), p. 235.

- Shirokogorov (1929), p. 204.

- Spinosa, Ludovico (2007). Wastewater Sludge. Iwa Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-1843391425.

- Wang, Yuchen; Lu Dongsheng; Chung Yeun-Jun; Xu Shuhua (2018). "Genetic structure, divergence and admixture of Han Chinese, Japanese and Korean populations" (PDF). Hereditas. 155: 19. doi:10.1186/s41065-018-0057-5. PMC 5889524. PMID 29636655.

- Wang, Yuchen; Lu, Dongsheng; Chung, Yeun-Jun; Xu, Shuhua (2018). "Genetic structure, divergence and admixture of Han Chinese, Japanese and Korean populations". Hereditas (published April 6, 2018). 155: 19. doi:10.1186/s41065-018-0057-5. PMC 5889524. PMID 29636655.

- "East Asia in the 21st Century | Boundless World History". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012-11-20). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-6517-8.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017-01-11). A History of East Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-11873-7.

- Ball, Desmond (2005). The Transformation of Security in the Asia/Pacific Region. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-0714646619.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 119.

- Amy Chua; Jed Rubenfeld (2014). The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America. Penguin Press HC. p. 121. ISBN 978-1594205460.

- Kang, David C. (2012). East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute. Columbia University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0231153195.

- Goucher, Candice; Walton, Linda (2012). World History: Journeys from Past to Present. Routledge (published September 11, 2012). p. 232. ISBN 978-0415670029.

- Smolnikov, Sergey (2018). Great Power Conduct and Credibility in World Politics. ISBN 9783319718859.

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Greenwood. p. 3. ISBN 978-0313336843.

- Warren I. Cohen. East Asia at the Center : Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. ISBN 0231101082

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0521296533.

- Cohen, Warren (2000). East Asia at the Center : Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0231101080.

- Chua, Amy (2009). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance--and Why They Fall. Anchor. p. 62. ISBN 978-1400077410.

- Leibo, Steve (2012). East and Southeast Asia 2012. Stryker Post. p. 19. ISBN 978-1610488853.

- Tsai, Henry (2009-02-15). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0765623287.

- Kshetry, Gopal (2008). Foreigners in Japan: A Historical Perspective. Xlibris Corp. p. 30. ISBN 978-1425770495.

- Kshetry, Gopal (2008). Foreigners in Japan: A Historical Perspective. Xlibris Corp. p. 31. ISBN 978-1425770495.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 2–3.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 7.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 2–3.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 7.

- Fagan, Brian M. (1999). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0195076189.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 8.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays: 8.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2009). Societies Networks And Transitions: Volume B From 600 To 1750. Wadsworth. pp. 290–291. ISBN 978-1-4390-8540-0.

- Embree, Ainslie; Gluck, Carol (1997). Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. M.E. Sharpe. p. 352. ISBN 9781563242656.

Japan culture tang dynasty.

- Kshetry, Gopal (2008). Foreigners in Japan: A Historical Perspective. Xlibris Corp. p. 32. ISBN 978-1425770495.

- Brown, John (2006). China, Japan, Korea: Culture and Customs. Createspace Independent. p. 33. ISBN 978-1419648939.

- Lind, Jennifer (February 13, 2018). "Life in China's Asia: What Regional Hegemony Would Look Like". Foreign Affairs.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays.

- Ellington, Lucien (2009). Japan (Nations in Focus). p. 21.

- John M. Roberts (1997). A Short History of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-19-511504-X.

- Hayes, Louis D (2009). Political Systems of East Asia: China, Korea, and Japan. Greenlight. pp. xi. ISBN 978-0765617866.

- Hayes, Louis D (2009). Political Systems of East Asia: China, Korea, and Japan. Greenlight. p. 15. ISBN 978-0765617866.

- Tindall, George Brown; Shi, David E. (2009). America: A Narrative History (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company (published November 16, 2009). p. 926. ISBN 978-0393934083.

- April, K.; Shockley, M. (2007). Diversity: New Realities in a Changing World. Palgrave Macmillan (published February 6, 2007). pp. 163. ISBN 978-0230001336.

- Cohen, Warren (2000). East Asia at the Center : Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0231101080.

- Batty, David (2005-01-17). Japan's War in Colour (documentary). TWI.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Asian History Module Learning. Rex Bookstore Inc. 2002. p. 186. ISBN 978-9712331244.

- Goldman, Merie; Gordon, Andrew (2000). Diversity: New Realities in a Changing World. Harvard University Press (published August 15, 2000). p. 3. ISBN 978-0674000971.

- Cohen, Warren (2000). East Asia at the Center : Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0231101080.

- Shiping, Hua; Hu, Amelia (2014). East Asian Development Model: Twenty-first century perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge (published 2014-12-09). pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0415737272.

- Lee, Yong Wook; Key, Young Son (2014). China's Rise and Regional Integration in East Asia: Hegemony or community? (1st ed.). Routledge (published March 14, 2014). p. 45. ISBN 978-0313350825.

- "Sino-Japanese War (1894–95)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- "The Japanese Economy". Walk Japan. 2010-12-16.

- Tindall, George Brown; Shi, David E. (2009). America: A Narrative History (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company (published November 16, 2009). p. 1147. ISBN 978-0393934083.

- Northrup, Cynthia Clark; Bentley, Jerry H.; Eckes Jr., Alfred E. (2004). Encyclopedia of World Trade: From Ancient Times to the Present. Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 978-0765680587.

- Paul, Erik (2012). Neoliberal Australia and US Imperialism in East Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 114. ISBN 978-1137272775.

- "Introducing East Asian Peoples" (PDF). International Mission Board. September 10, 2016.

- Gilbet Rozman (2004), Northeast asia's stunted regionalism: bilateral distrust in the shadow of globalization. Cambridge University Press, pp. 3-4

- "Northeast Asia dominates patent filing growth." Retrieved on August 8, 2001.

- "Paper: Economic Integration in Northeast Asia." Retrieved on August 8, 2011.

- Kim, Johnny S. (2013). Solution-Focused Brief Therapy: A Multicultural Approach. Sage Publications. p. 55. ISBN 978-1452256672.

- Shiping, Hua; Hu, Amelia (2014). East Asian Development Model: Twenty-first century perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge (published 2014-12-09). p. 3. ISBN 978-0415737272.

- Ness, Immanuel; Bellwood, Peter (2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell (published 2014-11-10). p. 217. ISBN 978-1118970591.

- Kort, Michael (2003). The Handbook Of East Asia. 21st Century. p. 7–9. ISBN 978-0761326724.

- Spinosa, Ludovico (2007). Wastewater Sludge. Iwa Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-1843391425.

- Prescott, Anne (2015). East Asia in the World: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0765643223.

- Ikeo, Aiko (1996). Economic Development in Twentieth-Century East Asia: The International Context. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0415149006.

- Yoshimatsu, H. (2014). Comparing Institution-Building in East Asia: Power Politics, Governance, and Critical Junctures. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 1. ISBN 978-1137370549.

- Kim, Mikyoung (2015). Routledge Handbook of Memory and Reconciliation in East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415835138.

- Hazen, Dan; Spohrer, James H. (2005). Building Area Studies Collections. Otto Harrassowitz (published 2005-12-31). p. 130. ISBN 978-3447055123.

- Grabowski, Richard; Self, Sharmistha; Shields, William (2012). Economic Development: A Regional, Institutional, and Historical Approach (2nd ed.). Routledge (published September 25, 2012). p. 59. ISBN 978-0765633538.

- Ng, Arden. "East Asia is the World's Largest Economy at $29.6 Trillion USD, Including 4 of the Top 25 Countries Globally". Blueback.

- Currie, Lorenzo (2013). Through the Eyes of the Pack. Xlibris Corp. p. 163. ISBN 978-1493145171.

- Asato, Noriko (2013). Handbook for Asian Studies Specialists: A Guide to Research Materials and Collection Building Tools. Libraries Unlimited. p. 1. ISBN 978-1598848427.

- Prescott, Anne (2015). East Asia in the World: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-0765643223.

- Miller, David Y. (2007). Modern East Asia: An Introductory History. Routledge. p. xi. ISBN 978-0765618221.

- "Central Themes for a Unit on China | Central Themes and Key Points | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-01. "Within the Pacific region, China is potentially a major economic and political force. Its relations with Japan, Korea, and its Southeast Asian neighbors, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, will be determined by how they perceive this power will be used."

- Cummings, Sally N. (2013). Understanding Central Asia: Politics and Contested Transformations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-43319-3.

- Saez, Lawrence (2012). The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC): An emerging collaboration architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-67108-1.

- Cornell, Svante E. Modernization and Regional Cooperation in Central Asia: A New Spring? (PDF). Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies.

- Aminian, Nathalie; Fung, K.C.; Ng, Francis. "Integration of Markets vs. Integration by Agreements" (PDF). Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank.

- "Northeast Asia." Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia (1999). Japan and Russia in Northeast Asia: Partners in the 21st Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 248.

- "United Nations Statistics Division – Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)". United Nations Statistics Division. 2015-05-06. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". United Nations Statistics Division. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Christopher M. Dent (2008). East Asian regionalism. London: Routledge. pp. 1–8.

- Charles Harvie, Fukunari Kimura, and Hyun-Hoon Lee (2005), New East Asian regionalism. Cheltenham and Northamton: Edward Elgar, pp. 3–6.

- Peter J. Katzenstein and Takashi Shiraishi (2006), Beyond Japan: the dynamics of East Asian regionalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 1–33

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020". IMF.

- Listed as "Hong Kong SAR" by IMF

- Listed as "Macao SAR" by IMF

- "Country codes". iso.org.

- From 1949 to 1971, the ROC was referred as "China" or "Nationalist China".

- "Country codes". iso.org.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "| Human Development Reports". www.hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- Seoul was the de jure capital of the DPRK from 1948 to 1972.

- Taipei is the ROC's seat of government by regulation. Constitutionally, there is no official capital appointed for the ROC.

- 人口推計 – 平成 28年 12月 報 (PDF).

- "新疆维吾尔自治区统计局". www.xjtj.gov.cn.

- Gordon, Raymond G. Jr., ed. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th ed.). Dallas: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6. OCLC 224749653.

- Lim, SK (2011-11-01). Asia Civilizations: Ancient to 1800 AD. ASIAPAC. p. 56. ISBN 978-9812295941.

- Goscha, Christopher (2016). The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam: A History. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1846143106.

- Amy Chua; Jed Rubenfeld (2014). The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America. Penguin Press HC. p. 122. ISBN 978-1594205460.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 2.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2012). China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty. Belknap Press (published April 9, 2012). p. 156. ISBN 978-0674064010.

- Reischauer, Edwin O. (1974). "The Sinic World in Perspective". Foreign Affairs. 52 (2): 341–348. doi:10.2307/20038053. JSTOR 20038053.

- Lim, SK (2011-11-01). Asia Civilizations: Ancient to 1800 AD. ASIAPAC. p. 89. ISBN 978-9812295941.

- Richter, Frank-Jurgen (2002). Redesigning Asian Business: In the Aftermath of Crisis. Quorum Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-1567205251.

- Vohra 1999, p. 22

- Amy Chua; Jed Rubenfeld (2014). The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America. Penguin Press HC. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1594205460.

- Wenzel-Teuber, Katharina (2012). "People's Republic of China: Religions and Churches Statistical Overview 2011" (PDF). Religions & Christianity in Today's China. II (3): 29–54. ISSN 2192-9289. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2017.

- Wenzel-Teuber, Katharina (2017). "Statistics on Religions and Churches in the People's Republic of China – Update for the Year 2016" (PDF). Religions & Christianity in Today's China. VII (2): 26–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2017.

- Shirley Kan (December 2009). Taiwan: Major U.S. Arms Sales Since 1990. DIANE Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4379-2041-3.

- United Nations (March 12, 2017). "The World's Cities in 2016" (PDF). United Nations.

- 통계표명 : 주민등록 인구통계 (in Korean). Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

Further reading

- Church, Peter. A short history of South-East Asia (John Wiley & Sons, 2017).

- Clyde, Paul H., and Burton F. Beers. The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975 (1975) online 3rd edition 1958

- Crofts, Alfred. A history of the Far East (1958) online free to borrow

- Dennett, Tyler. Americans in Eastern Asia (1922) online free

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Anne Walthall. East Asia: A cultural, social, and political history (Cengage Learning, 2013).

- Embree, Ainslie T., ed. Encyclopedia of Asian history (1988)

- Fairbank, John K., Edwin Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig. East Asia: The great tradition and East Asia: The modern transformation (1960) [2 vol 1960] online free to borrow, famous textbook.

- Flynn, Matthew J. China Contested: Western Powers in East Asia (2006), for secondary schools

- Gelber, Harry. The dragon and the foreign devils: China and the world, 1100 BC to the present (2011).

- Green, Michael J. By more than providence: grand strategy and American power in the Asia Pacific since 1783 (2017) a major scholarly survey excerpt

- Hall, D.G.E. History of South East Asia (Macmillan International Higher Education, 1981).

- Holcombe, Charles. A History of East Asia (2d ed. Cambridge UP, 2017). excerpt

- Iriye, Akira. After Imperialism; The Search for a New Order in the Far East 1921-1931. (1965).

- Jensen, Richard, Jon Davidann, and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds. Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century (Praeger, 2003), 304 pp online review

- Keay, John. Empire's End: A History of the Far East from High Colonialism to Hong Kong (Scribner, 1997). online free to borrow

- Levinson, David, and Karen Christensen, eds. Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. (6 vol. Charles Scribner's Sons, 2002).

- Mackerras, Colin. Eastern Asia: an introductory history (Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, 1992).

- Macnair, Harley F. & Donald Lach. Modern Far Eastern International Relations. (2nd ed 1955) 1950 edition online free, 780pp; focus on 1900-1950.

- Miller, David Y. Modern East Asia: An Introductory History (Routledge, 2007)

- Murphey, Rhoads. East Asia: A New History (1996)

- Norman, Henry. The Peoples and Politics of the Far East: Travels and studies in the British, French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies, Siberia, China, Japan, Korea, Siam and Malaya (1904) online

- Paine, S. C. M. The Wars for Asia, 1911-1949 (2014) excerpt

- Prescott, Anne. East Asia in the World: An Introduction (Routledge, 2015)

- Ring, George C. Religions of the Far East: Their History to the Present Day (Kessinger Publishing, 2006).

- Szpilman, Christopher W. A., Sven Saaler. "Japan and Asia" in Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History (2017) online

- Steiger, G. Nye. A history of the Far East (1936).

- Vinacke, Harold M. A History of the Far East in Modern Times (1964) online free

- Vogel, Ezra. China and Japan: Facing History (2019) excerpt

- Woodcock, George. The British in the Far East (1969) online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eastern Asia. |

| Look up east asia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for East Asia. |