Eau de Cologne

Eau de Cologne (French: [o d(ə) kɔlɔɲ]; German: Kölnisch Wasser [ˈkœlnɪʃ ˈvasɐ]; meaning "Water from Cologne"), or simply cologne, is a perfume originating from Cologne, Germany.[1] Originally mixed by Johann Maria Farina (Giovanni Maria Farina) in 1709, it has since come to be a generic term for scented formulations in typical concentration of 2–5% and also more depending upon its type essential oils or a blend of extracts, alcohol, and water.[2] In a base of dilute ethanol (70–90%), eau de cologne contains a mixture of citrus oils including oils of lemon, orange, tangerine, clementine, bergamot, lime, grapefruit, blood orange, and bitter orange. It can also contain oils of neroli, lavender, rosemary, thyme, oregano, petitgrain (orange leaf), jasmine, olive, oleaster, and tobacco.

In contemporary American English usage, the term "cologne" has become a generic term for perfumes usually marketed toward men. It also may signify a less concentrated, more affordable, version of a popular perfume.

History

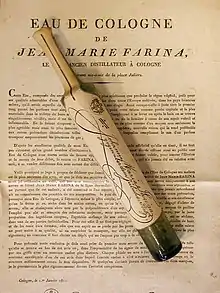

The original Eau de Cologne is a spirit-citrus perfume launched in Cologne in 1709 by Giovanni Maria Farina (1685–1766), an Italian perfume maker from Santa Maria Maggiore Valle Vigezzo. In 1708, Farina wrote to his brother Jean Baptiste: "I have found a fragrance that reminds me of an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils and orange blossoms after the rain".[3] He named his fragrance Eau de Cologne, in honour of his new hometown.[4]

The Original Eau de Cologne 4711, is named after its location at Glockengasse No. 4711. It was also developed in the 18th century by Wilhelm Mülhens and produced in Cologne since at least 1799 and is therefore probably one of the oldest still produced fragrances in the world. On 12 December 2006, the perfumes and cosmetics company Mäurer & Wirtz took over 4711 from Procter & Gamble and has expanded it to a whole brand since then.

The Eau de Cologne composed by Farina was used only as a perfume and delivered to "nearly all royal houses in Europe".[5] His ability to produce a constantly homogeneous fragrance consisting of dozens of monoessences was seen as a sensation at the time. A single vial of this aqua mirabilis (Latin for miracle water) cost half the annual salary of a civil servant.[4] When free trade was established in Cologne by the French in 1797, the success of Eau de Cologne prompted countless other businessmen to sell their own fragrances under the name of Eau de Cologne. Giovanni Maria Farina's formula has been produced in Cologne since 1709 by Farina opposite the Jülichplatz[4] and to this day remains a secret. His shop at Obenmarspforten opened in 1709 and is today the world's oldest fragrance factory.

In 1806, Jean Marie Joseph Farina, a grand-grand-nephew of Giovanni Maria Farina, opened a perfumery business in Paris that was later sold to Roger & Gallet. That company now owns the rights to Eau de Cologne extra vieille in contrast to the Original Eau de Cologne from Cologne. Originally the water of Cologne was believed to have the power to ward off bubonic plague.[6] By drinking the cologne the citrus oil scent would be exuded through the pores, repelling fleas. Much as flea shampoo for dogs can be based on citrus oils today.

In modern times, eau de Cologne or "cologne", has become a generic term. The term "cologne" can be applied to perfume for men or women, but it conventionally refers to perfumes marketed toward men.[7]

The importation of Eau de Cologne into Turkey resulted in the creation of kolonya, a Turkish perfume.[8]

Literary Reference

Yevgeny Yevtushenko's Poem, About Drinking, describes the author coming back from a whaling voyage and arriving at a small town where the local store is out of spirits and instead they find a case of Eau de Cologne to drink.

See also

Bibliography

- Fenaroli, Giovanni; Maggesi, L. (1960). "Acqua di Colonia". Rivista italiana essenze, profumi, piante offizinali, olii vegetali, saponi (in Italian). 42.

- La Face, Francesco (1960). "Le materie prime per l'acqua di colonia". Relazione al Congresso di Sta. Maria Maggiore (in Italian).

- Monk, Paul M. S. (May 2004). Physical Chemistry: Understanding Our Chemical World. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-49181-1.

- Sabetay, Sébastien (1960). Les Eaux de Cologne Parfumée. Sta. Maria Maggiore Symposium (in French).

- Wells, Frederick V. (1960). Variations on the Eau de Cologne Theme. Sta. Maria Maggiore Symposium.

- Wells, Frederick V.; Billot, Marcel (1981). Perfumery Technology. Art, science, industry. Chichester: Horwood Books. pp. 25, 278. ISBN 0-85312-301-2.

- Wilhelm, Jürgen, ed. (2005). Das große Köln-Lexikon (in German). Cologne: Greven Verlag. ISBN 3-7743-0355-X.

References

- Citations

- "Perfume & Cologne Market 2019-2025 | Professional Survey By ICRW". Big Fashion trends. 2019-09-20. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- "Finding Queen Victoria's perfume". Royal Central. 2019-05-12. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- Eckstein and Sykes, p 8

- Fischer

- Farina Fragrance Museum information leaflet

- Monk, Paul M. S. Physical Chemistry: Understanding Our Chemical World. 2004. Wiley.

- "The history behind eau de cologne". Germany Wanderer. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Yalav-Heckeroth, Feride. "A Brief History Of Kolonya, Turkey's Fragrance". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- Works cited

- Eckstein, Markus; Sykes, John (2009). Eau de Cologne: Farina's 300th Anniversary. Cologne: J. P. Bachem. ISBN 978-3-7616-2313-8.

- Fischer, Carmen (2011). "'Französisch Kram' aus Köln" (PDF). Damals (in German). Vol. 43 no. 6. pp. 70–71.

- Information leaflet of the Farina Fragrance Museum at Cologne

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eau de Cologne. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |