Edward Thomas Daniell

Edward Thomas Daniell (6 June 1804 – 24 September 1842) was an English artist known for his etchings and the landscape paintings he made during an expedition to the Middle East, including Lycia, part of modern-day Turkey. He is associated with the Norwich School of painters, a group of artists connected by location and personal and professional relationships, who were mainly inspired by the Norfolk countryside.

Edward Thomas Daniell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 June 1804 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 24 September 1842 (aged 38) |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Norwich Grammar School; Oxford University |

| Known for | Landscape painting; etching |

Notable work | etchings of Norfolk (e.g., Flordon Bridge, Whitlingham Lane by Trowse) and watercolours of the Middle East |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

Born in London to wealthy parents, Daniell grew up and was educated in Norwich, where he was taught art by John Crome and Joseph Stannard. After graduating in classics at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1828, he was ordained as a curate at Banham in 1832 and appointed to a curacy at St. Mark's Church, London, in 1834. He became a patron of the arts, and an influential friend of the artist John Linnell. In 1840, after resigning his curacy and leaving England for the Middle East, he travelled to Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and joined the explorer Sir Charles Fellows's archaeological expedition in Lycia (now in Turkey) as an illustrator. He contracted malaria there and reached Adalia (now known as Antalya) intending to recuperate, but died from a second attack of the disease.

He normally used a small number of colours for his watercolour paintings, mainly sepia, ultramarine, brown pink and gamboge. The distinctive style of his watercolours was influenced in part by Crome, J. M. W. Turner and John Sell Cotman. As an etcher he was unsurpassed by the other Norwich artists in the use of drypoint,[3] and he anticipated the modern revival of etching which began in the 1850s. His prints were made by his friend and neighbour Henry Ninham, whose technique he influenced. His paintings of the Near East may have been made with future works in mind.

Background

Edward Daniell was associated with the Norwich School of painters, a regional school of landscape painters who were connected personally or professionally. Though mainly inspired by the Norfolk countryside, many also depicted other landscapes, and coastal and urban scenes.[5]

The school's most important artists were John Crome, Joseph Stannard, George Vincent, Robert Ladbrooke, James Stark, John Thirtle and John Sell Cotman, along with Cotman's sons Miles Edmund and John Joseph Cotman. The school was a unique phenomenon in the history of 19th-century British art:[6] Norwich was the first English city outside London which had the right conditions for a provincial art movement.[7][8] It had more locally born artists than any other similar city,[9] and its theatrical, artistic, philosophical and musical cultures were cross-fertilised in a way that was unique outside the capital.[7][10]

The Norwich Society of Artists, which was founded by Crome and Ladbrooke in 1803,[11] arose from the need for a group of Norwich artists to teach each other and their pupils. The Society held regular exhibitions and had an organised structure, showing works annually until 1825 and again from 1828 until it was dissolved in 1833.[12] Not all the members of the Norwich School belonged to the Society.[13]

At the end of the seventeenth century, other schools of painting had begun to form, associated with artists such as Francis Towne at Exeter and John Malchair at Oxford. Other centres of population outside London were creating art societies, whose artists and drawing masters influenced their pupils.[14] Unlike the artists of the Norwich School, these provincial artists did not benefit from wealthy merchants and landed gentry demonstrating their patriotism by acquiring picturesque paintings of the English countryside.[15] The Norwich Society of Artists, the first group of its kind to be created since the formation of the Royal Academy in 1768, was remarkable in acting in its artists' interests for thirty years, a longer period than for any other similar group.[16]

Life

Early life and education

Edward Thomas Daniell was born on 6 June 1804 at Charlotte Street in central London, to Sir Thomas Daniell, a retired attorney-general of Dominica, and his second wife Anne Drosier, the daughter of John Drosier of Rudham Grange, Norfolk.[17][18] Sir Thomas' first wife, with whom he had a son Earle and a daughter Anne, died in London in 1792. Their daughter married John Holmes in Norfolk in 1802 and died in childbirth in 1805.[19][20][21] Her brother Earle was an officer in the 12th Dragoons by 1806.[22]

Sir Thomas purchased land and slaves in the Leeward Islands, which were then part of the British Empire. His estates, including 291 acres (118 ha) at Dickenson Bay on Antigua, had been bought in 1779 from the family of his first wife.[22] He retired and moved to the west of Norfolk,[24] but his health deteriorated and he died of cancer in 1806, leaving a young widow and infant son.[25][note 3] He left his Dominican lands to her, and his Antigua estate to his adult son Earle, subject to him providing a guaranteed annual income of £300 to the family in Norfolk.[29] Anne Daniell and her son moved to a house in St. Giles Street, Norwich.[18] She died in 1836 aged 64, and was buried in the nave of St Mary Coslany.[30]

Edward Daniell grew up with his mother in Norwich and was educated at Norwich Grammar School, where the drawing master was John Crome.[31][17] He was involved in the art world at a young age; the brothers Thomas and Chambers Hall wrote to the artist John Linnell in 1822 about "our young friend Mr Daniells [sic] who accompanied us to your house last week and who wishes to possess a drawing".[32]

On 9 December 1823, aged 19, Daniell went to Balliol College, Oxford to read classics.[31] He graduated in November 1828,[33] despite having neglected his studies in favour of art.[32] In a letter to Linnell, he wrote: "I find that the examinations for which I am preparing next month require a closer application to my literary studies than I had imagined and that I must not attempt to 'serve two masters'."[32] He was introduced to etching by Joseph Stannard, and during the holidays practiced at Stannard's studio in St. Giles Terrace, around the corner from his own house.[31][17] He graduated with a Master of Arts on 25 May 1831.[32]

Travels in Europe and Scotland

Daniell had the financial means to travel abroad to find subjects to paint;[34] of the Norwich School painters, only John Sell Cotman travelled further.[35] During 1829 and 1830 Daniell spent the months between his classics studies and his master's degree on a Grand Tour through France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland, producing scenic oil paintings and watercolours that the art historian William Dickes described as "well-centred performances, painted with a fluid brush, and revealing a delicate appreciation of tone".[36][37]

The route Daniell took during his eighteen months on the Continent is revealed by the order of his paintings.[32] His travels through Switzerland are reminiscent of those of the artist James Pattison Cockburn, who published his Swiss Scenery in 1820.[38] In Rome and Naples he met the artist Thomas Uwins, who wrote: "What a shoal of amateur artists we have got here! ... there is a Daniel too come to judgement! a second Daniel! – Verily, I have gotten more substantial criticism from this young man than from anyone since Havell was my messmate."[39]

Daniell may also have visited Spain, as his etchings of the country were copied by the Norwich artist Henry Ninham, but there is no direct evidence he went there. It is possible he returned home in time for the funeral of Joseph Stannard, who died from tuberculosis on 7 December 1830, aged 33.[32]

In the summer of 1832, Daniell went on a walking trip in Scotland, accompanied by two contemporaries from Oxford, George Denison and Edmund Walker Head.[40] The trip provided him with subject material [41] and influenced his use of drypoint etching, as he was able to study the work of etchers such as Andrew Geddes.[42] In The Etchings of E. T. Daniell, Jane Thistlethwaite wrote that his Scottish scenes "testify in their subjects to his enthusiasm for the beauties of Scotland and in their technique to his almost certain acquaintance with the Scottish etchers".[40]

Church career

.jpg.webp)

On 2 October 1832 Daniell was ordained in Norwich Cathedral as a deacon, and three days later was licensed as the curate of the parish church at Banham, a post he held for eighteen months.[40] Letters to John Linnell show he felt a need to increase his income during this period in his life.[40] Little is known of his career as a Norfolk curate, but the Banham registers, all of which have been preserved, show he led an active life in the parish. He continued to etch at this time, and in Thistlethwaite's view whilst there produced his "loveliest and most sophisticated plates".[40]

On 2 June 1833, Daniell was ordained to the priesthood, but continued as the curate at Banham until 1834. That year he was appointed to the curacy of St. Mark's, North Audley Street in London, and took rooms in Park Street, Mayfair.[43][40] He also worked at St. George's Hospital, but as with his curacy at St. Mark's, no official records of his employment have survived.[40] In a letter written in 1835 to his Oxford tutor Joseph Blanco White, Daniell wrote: "You probably, thought I was haranguing the plough-boys in Norfolk, and you find me among the Dons of Grosvenor Square, and having to preach (as I must) next Wednesday at St. George's, Hanover Square. I wish you would come and give me some assistance."[44] In about 1836 he moved to rooms in Green Street, near Grosvenor Square and close to St. Mark's, living there until his departure for the Holy Land in 1840.[45]

The outer shell of Norwich Castle's keep was refaced in Bath stone from 1834 to 1839, replicating the original blank arcading.[46] Daniell was among those who strongly opposed the proposed refacing. Letters written from London show that he had not forgotten this contentious issue. He planned a plate of Ninham's drawing of the castle as a gesture of his opposition to the project,[40] informing the antiquary Dawson Turner that "I have had a very beautiful drawing made of it, and I mean to etch it the size of the drawing." His etching of the old keep was never completed.[47]

Tour of the Near East

At some date after June 1840,[41] perhaps inspired by the Scottish painter David Roberts who had travelled to Egypt and the Holy Land to find landscapes to depict,[note 4] Daniell resigned his curacy and left England to tour the Near East.[49] He arrived in Corfu in September 1840.[17] Although Roberts' paintings of the Middle East are thought to have compelled him to tour abroad, he had also been told of recent discoveries in Lycia (now part of modern Turkey) by the explorer Charles Fellows.[50]

Daniell was in Athens by the end of the year, and sailed to Alexandria early in 1841. He travelled up the Nile to Nubia, and then from Egypt to Palestine, on a route that took him past Mount Sinai. He reached Beirut in October 1841.[50]

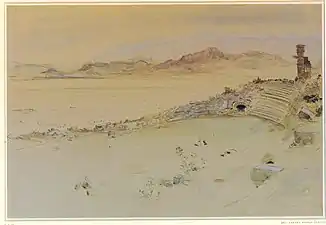

He met Fellows in the Turkish city of Smyrna and joined his expedition, boarding HMS Beacon, a ship sent by the British Government to convey home antiquities recently discovered by Fellows at Xanthos.[51] During the expedition 18 ancient cities were located.[52] After spending the winter at Xanthos, Daniell chose to remain in Lycia to help survey the region, in company with Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and the naturalist Edward Forbes.[53] Spratt was responsible for researching the area's topography and Forbes its natural history; Daniell was to make records of any discoveries.[49] In Lycia he produced a series of watercolours, later commented on by the academic Laurence Binyon, who said, "What strikes one most at first is the astonishing air of space and magnitude conveyed, the fluid wash of sunlight in these towering gorges and open valleys."[54]

In March 1842, Fellows left for London on HMS Beacon, in order to obtain bigger ships for transporting the antiquities back to England.[49] Daniell travelled to Selge, sketching and exploring its ruins.[55] He made copies of inscriptions from monuments in Cibyratis, Pisidia and Pamphylia,[56] and visited Sillyon, Marmara, Perga and Lyrbe.[57][note 5] His original drawings are now lost, but they were later published in Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis, in company with the Late E. T. Daniell, and his notes were transcribed (inaccurately) by Samuel Birch at the British Museum. Birch's collection contains a single page of Daniell's original manuscript.[56]

The expedition arrived at Adalia (now known as Antalya) in April 1842. Spratt and Forbes left the city before Daniell, who travelled overland after meeting the Pasha.[58] He then visited Cyprus and painted a watercolour of the island, possibly while anchored off shore.[59] The author Rita Severis has compared his painting with the watercolours of Turner, whom he was known to admire. In her book on artistic representations of the island from 1700 to 1960, she wrote: "The interplay of the blue sea and the sandy colour of the land – which is repeated successfully in the foreground of the picture – accentuates the distance between the viewer and the land while simultaneously increasing the desire to look more closely and attentively at the subject."[60]

Death

In late May 1842 the ships HMS Monarch and Media arrived and Daniell accepted an offer of a passage to England.[49] In June he left Rhodes to return to Lycia and rejoin Forbes and Spratt,[57] but he missed his ship – Monarch and Media had set sail the previous day – and was forced to amend his plans.[61] There was a chance to return to Rhodes by caïque and join the returning ships,[61] but he instead travelled to Adalia with the newly-appointed consul for the city, John Purdie. During the journey Daniell became feverishly ill with malaria,[62][63] contracted, according to Forbes and Spratt, "by lingering too long among the unhealthy marshes of the Pamphylian coast".[63]

.jpg.webp)

He stayed at Purdie's residence to recuperate,[63] and wrote to Forbes and Spratt describing his discoveries at Apollonia and Lyrbe.[64] Before he had fully recovered he left the city to undertake a solitary expedition to Pamphylia and Pisidia, travelling during the hottest part of the year.[62] He was forced back to Adalia after suffering a second attack of malaria,[64] and at Purdie's house dictated what was to be his last letter, which expressed his intentions to continue his work.[65][note 6] He lost consciousness after sleeping whilst exposed to the heat of the day on the front terrace of Purdie's residence, and died a week later, on 24 September. He was buried in the city.[67][note 7] The Norfolk historian Frederick Beecheno[69] wrote in 1889 that Daniell was "buried beneath an ancient granite column in the court of a Greek church in the centre of the town of Adalia".[51]

Forbes paid tribute to his friend Daniell, writing that his illness "destroyed a traveller whose talents, scholarship, and research would have made Lycia a bright spot on the map of Asia Minor, and whose manliness of character and kindness of heart endeared him to all who had the happiness of knowing him".[55]

A memorial was placed near his tomb in Antalya "by his affectionate and grieving relatives".[63] Another memorial can be seen in Norwich, on the wall of the church of St. Mary Coslany. His will is preserved in the National Archives at Kew.[70]

Friends and associates

Many of Daniell's etchings were printed in Norwich by Henry Ninham, who lived a short distance from Daniell's house on St. Giles Street.[41] His friendships with Ninham and Joseph Stannard may have begun at school.[32]

Daniell was an active patrons of the arts[43] and held regular dinner parties and other gatherings at his London home.[71] It became a resort of painters including John Linnell, David Roberts, William Mulready, William Dyce, Thomas Creswick, Edwin Landseer, William Collins, Abraham Cooper, John Callcott Horsley, Charles Lock Eastlake, J. M. W. Turner and William Clarkson Stanfield. Alfred Story, Linnell's biographer, described Daniell's home as "a treasure-house of art, (which) comprised works by some of the best painters of the day".[72][40]

One of Daniell's pupils was the writer Elizabeth Rigby, who remembered him as the "old friend" who had introduced her to etching and admired her drawings. In 1891 she wrote: "My recollection of his face was that of one of the openest that could be seen – a superb forehead, and splendid teeth, which showed themselves with every smile, and no one smiled and laughed more genially."[73]

John Linnell

Daniell first met the artist John Linnell while he was at Oxford. Linnell asked him to promote the sale of Illustrations of the Book of Job by the artist and poet William Blake, who was Linnell's great friend.[74] Daniell commissioned him to produce the painting now known as View of Lymington, the Isle of Wight beyond for the price of thirty guineas. At a later date, he exchanged it for Boy Minding Sheep, paying the difference of twenty guineas. In 1828 Linnell made a portrait miniature of Daniell and taught him how to paint in oils.[36][17]

They corresponded regularly and Linnell was a frequent guest at Daniell's rooms in London.[75] Daniell encouraged him to complete his St. John the Baptist Preaching in the Wilderness (1828–1833), offering to buy it himself if it did not sell. When the painting was exhibited in 1839 at the British Institution, it helped to enhance Linnell's reputation as an artist.[76]

Before leaving for the Middle East, Daniell commissioned a portrait of J. M. W. Turner from Linnell. Turner had previously refused to sit for the artist, and it was difficult to get his agreement to be portrayed. Daniell positioned the two men opposite each other at dinner, so Linnell could observe Turner carefully and portray his likeness from memory. Due to Daniell's death, the completed painting was never delivered.[77]

When Linnell's painting Noon was rejected by the Royal Academy in 1840, Daniell came to his friend's assistance. The picture was taken to Daniell's house and hung above the fireplace, where it was admired by his dinner guests, including two members of the Academy. Daniell reprimanded them, saying "You are a pretty set of men to pretend to stand up for high art and to proclaim the Academy the fosterer of artistic talent, and yet allow such a picture to be rejected!"[78]

J. M. W. Turner

Daniell's friendship with Turner, whom he first met in London, was short but intense. He was a regular guest at Daniell's gatherings and dinner parties, and they quickly became close friends.[39] He was considered by Daniell's circle of artists to be their doyen.[79] Beecheno, in his E. T. Daniell: a memoir, recalled that on one occasion Turner was asked his opinion of Daniell's work. "Very clever, Sir, very clever" was the great master's dictum, delivered in his usual blunt way."[1] Elizabeth Rigby wrote of Daniell:[73]

His admiration for Turner inspired Turner with genuine affection for him. Boxall has told me that at an R.A. dinner, he and Turner sitting with one between them, Turner leant back, and touched Boxall to attract silently his attention, and then pointing to a glass of wine in his other hand, whispered solemnly, "Edward Daniell".

Roberts wrote that Daniell "adored Turner, when I and others doubted, and taught me to see and to distinguish his beauties over that of others ... the old man really had a fond and personal regard for this young clergyman, which I doubt he ever evinced for the other."[39]

He may have helped Turner spiritually. His biographer James Hamilton writes that he was "able to supply spiritual comfort that Turner required to help him fill the holes left by the deaths of his father and friends and to ease the fears of a naturally reflective man approaching old age".[39] The old artist is known to have mourned Daniell's early death deeply, saying repeatedly to Roberts that he would never form such a friendship again.[77] Roberts later wrote: "Poor Daniell, like Wilkie, went to Syria after me, but neither returned. Had Daniell returned to England, I have reason to know, from Turner's own mouth, he would have been entrusted with his law affairs."[40][note 8]

Turner's romantic style is approached by Daniell's watercolours painted during his travels abroad. Coincidentally, Turner toured Switzerland in 1829, visiting sites Daniell had earlier depicted.[38]

Works and artistic style

As the son of a baronet, Daniell was of a higher social class than his Norwich School contemporaries.[81] He lived during a time when "it was not suitable for young gentlemen to become artists",[50] and his private income and position as a curate meant he was to remain an amateur artist throughout his life;[42] in a letter to Rigby, he referred to himself as a "tree and house sketcher".[36][82]

The writer Derek Clifford believed Daniell's distinctive style was influenced by the methods of John Sell Cotman, an artist Daniell deeply admired,[83] but the art historian Andrew Moore writes that "his artistic influences are not readily established,"[18] and Searle notes that he had an "assured individuality that recalls no one else".[84] The historian Josephine Walpole, who believes Daniell's talent has yet to be properly recognised, has praised his ability to "create a sense of space, a feeling of heat or cold, of poverty or plenty, with apparent lack of effort".[85]

In 1832 Daniell exhibited a number of his own pictures of scenes in Italy, Switzerland and France with the Norwich Society of Artists, which were favourably commented upon by the Norwich Mercury. During the sole instance of an exhibition of his works with the Society,[41] he showed Sketch from Nature, Lake of Geneva, from Lausanne, painted on the spot. Ruins of a Claudian Aqueduct, in the Campagna di Roma, and Ruined Tombs, on the Via Nomentana, Rome, painted on the spot.[86]

He served on bodies involved with the arts,[87] becoming a Fellow of the Geological Society of London in 1835,[88] and a committee member of the Society for the Encouragement of British Art in May 1837.[50]

Oils and watercolours

Daniell's oil paintings generally depicted subjects encountered on his continental travels, and he showed them at annual exhibitions in London.[41] He was an honorary exhibitor with the Royal Academy, showing four pieces there: Sion in the Valais (1837); View of St. Malo (1838); Sketch from a picture of the Mountains of Savoy from Geneva (1839); and Kenilworth (1840), as well as four pictures at the British Institute (The Temple of Minerva (1836); Ruins of the Campagna of Rome (1838); Meadow scene (1839); and The Lake of Geneva, from near Lausanne (1840)).[23][89][90]

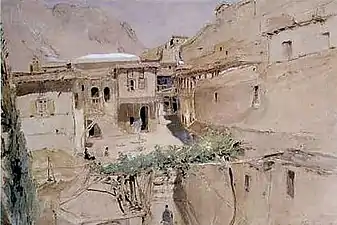

His watercolours draw from a deliberately limited palette, exemplified by the paintings from his tours of the Middle East, where he used sepia, ultramarine, brown pink and gamboge, with details emphasised using bistre, burnt sienna or white.[91] The 120 large sketches at Norwich Castle and the further 64 at the British Museum may have been made in preparation for future works that were never made.[92]

Daniell's watercolours have been highly praised by art historians. They were described by Hardie as "the perfection of free sketching".[3] Binyon described them as showing him "at the height of his subject",[54] and according to Andrew Hemingway, some of them are "magnificent".[93] In Moore's opinion, Daniell's "fluid, sensitive use of washes", testified by his early Bure Bridge, Aylsham,[18] ranks him alongside William James Müller and David Roberts,[37] and the drawings produced on his last tour "reveal a vision that emulates that of David Roberts and exceeds that of Edward Lear".[94][note 9] Clifford identified Daniell's distinctively bold style and sense of draughtsmanship,[83] but pointed out what he saw as weaknesses in some of the watercolours: a “fear” of using colour, the emptiness of some of the panoramic views, and an unsuitable use of coloured paper.[95]

Walpole sees Daniell's watercolours as having a style that "is all his own" – freely drawn, ambitious and "having a powerful feeling for the atmosphere of the landscape". She notes how his delicate outlines and distinctively varied tones convey a sense of space and give an illusion of detail, citing Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai as a watercolour that expresses to her all that is best about Daniell's "understated artistry".[96]

Burgh Bridge near Aylsham (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections

Burgh Bridge near Aylsham (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections Kobban (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections

Kobban (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections Near Kalabshee 1841, Norfolk Museums Collections

Near Kalabshee 1841, Norfolk Museums Collections Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections

Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections Termessus, looking SE (1842), British Museum

Termessus, looking SE (1842), British Museum Stadium of Cibyra (1842), British Museum

Stadium of Cibyra (1842), British Museum

Etchings

Daniell's 52 attributed etchings,[97] though small in number and not exhibited during his lifetime, are the basis for his reputation as an artist.[17][98] In 1899, Binyon considered his etchings to be – from a historical point of view – the most remarkable of his works, anticipating with their freedom of line the etching revival personified later in the century by Seymour Haden and James Abbott McNeill Whistler.[62] Malcolm Salaman, writing in the 1910s, observed:[99]

No etcher of this early English period evinced a truer and more subtle understanding and handling of the medium than Crome's pupil, the Rev. E. T. Daniell, a very interesting artist of the Norwich School, whose plates, etched in the eighteen-twenties, are remarkable for genuine etcher's vision, expressive charm, and delicacy of craft. His View of Whitlingham, full of light and air, proves him to be in the direct line of the masters.

In 1966, the author Martin Hardie asserted: "If only more proofs from his fine plates been made available for collectors and museums he would be more readily placed among the great etchers of the world."[3] Miklos Rajnai, a Keeper of Art at Norwich Castle Museum, compared Daniell's skill as an etcher with John Crome and John Sell Cotman.[42] The British art historian Arthur Hind said the etchings "anticipated far more than nearly anything of Crome or Cotman the modern revival of etching".[100]

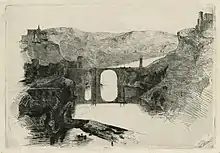

Daniell's first attempts at etching were made with Joseph Stannard in February 1824. The style of his earliest works were influenced by Stannard,[101] but he later became more affected by the works of J. M. W. Turner.[102] Three distinct groups of etchings can be identified: those produced in Norfolk, including Flordon Bridge, his masterpiece from his early years; a more grandiose group of etchings made during his tours of Scotland and the continent; and those made during his curacy at Banham, which includes his most assured work of this period, Whitlingham Lane near Trowse.[103] He stopped etching after his move to London.[104] Although his Norfolk prints are mostly landscapes, they were intended to be artistic rather than topographically accurate, and any figures were used simply to indicate the scale of the landscape they were set in.[50]

Daniell later employed a looser style, moving away from Stannard and towards that of Andrew Geddes and other Scottish etchers, whose output he almost certainly first saw while in Scotland during the summer of 1831.[37] His was outstanding in the use of drypoint, strengthening his design by using the needle's point to create a burr in the plate. The burrs allowed the ink to collect, producing a darker tone in some of his prints.[105] Thistlethwaite views the large drypoint etchings and Norfolk landscapes made after 1831 as being "supremely independent and for his time unique", once he had moved away from the traditional style of etchers like Geddes.[50] He is thought to have introduced drypoint etching to his Norwich peers; both Thomas Lound and Henry Ninham etched in this way after 1831, producing works of a quality approaching Daniell's own.[106]

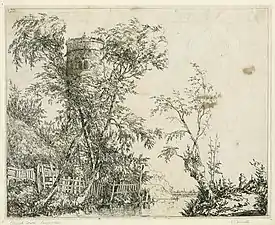

Church Tower and Trees (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections. This work is probably Daniell's first etching.[107]

Church Tower and Trees (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections. This work is probably Daniell's first etching.[107] River Scene with Man fishing from a Boat (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections

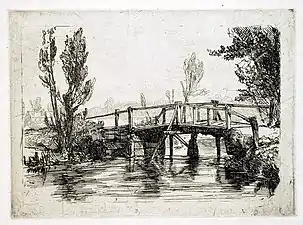

River Scene with Man fishing from a Boat (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections Flordon Bridge (1825), Norfolk Museums Collections

Flordon Bridge (1825), Norfolk Museums Collections Aylsham Bridge, or Burgh Bridge (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections

Aylsham Bridge, or Burgh Bridge (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections Castle of Dunolly, Oban (c. 1831), Norfolk Museums Collections

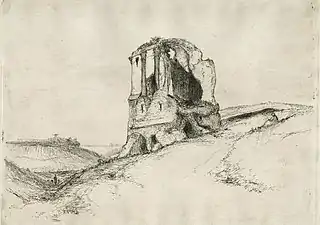

Castle of Dunolly, Oban (c. 1831), Norfolk Museums Collections Ruin at Rome (c. 1831), Norfolk Museums Collections

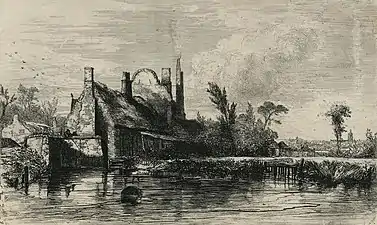

Ruin at Rome (c. 1831), Norfolk Museums Collections Whitlingham Lane by Trowse (c. 1833), Norfolk Museums Collections

Whitlingham Lane by Trowse (c. 1833), Norfolk Museums Collections At Banham, Norfolk (c. 1833), Norfolk Museums Collections

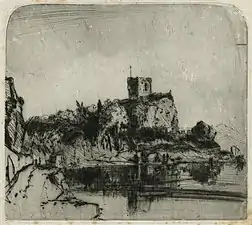

At Banham, Norfolk (c. 1833), Norfolk Museums Collections Norwich Castle – before the restoration of 1834, Norfolk Museums Collections

Norwich Castle – before the restoration of 1834, Norfolk Museums Collections

Legacy

Most of Daniell's works form part of the Norfolk Museums Collections, or are held at the British Museum, which obtained some of them before 1852 and purchased his prints as early as 1856.The original impressions are generally held in public collections. Binyon's biographical article appeared in 1889. [98]

Although none of Daniells' etchings were exhibited or published during his lifetime, some were given to friends. They were first shown in public in 1891 in a Norwich Arts Circle exhibition.[104] In 1882, the economist Inglis Palgrave wrote Twelve Etchings of the Rev. E. T. Daniell,[108] and 24 copies of the book were printed, one of which is at the Victoria & Albert Museum. The book was never published.[109] In 1921, Hardie delivered a lecture to the Print-Collectors' Club in which he discussed Daniell's plates.[100] He has described them as "full of interest and technical value, and at the same time curiously modern in their spirit", adding of him: "He reaches a very high level of refined thought and execution in his Borough Bridge."[110]

Daniell's Middle East landscapes have provided important documentary evidence of the region during the 1840s.[111] His works were exhibited at Aldeburgh in 1968,[98] and at From Norfolk to Nubia: The Watercolours of E.T. Daniell, an exhibition held at Norwich Castle in 2016.[112][113]

Notes

- A watercolour copy of the portrait of Daniell remained with Linnell and was in his studio at Linnell's death, an indication of the personal attachment he felt for his friend.[2]

- Anne Daniell's portrait was painted in Norwich by Daniell's friend Linnell a year before her death.[23]

- Thomas Daniell died at Snettisham Lodge on 17 March 1806,[26] and was buried at Snettisham the following week. The tablet to his memory in Snettisham Church gives his age as 53, but the parish records show he died at 73.[27][28]

- On 8 February 1840, Linnell's diary mentioned: "To Mr. Daniell to see Roberts's drawings of Egypt and Palestine, etc."[48]

- Most of the 200 inscriptions found by the expedition were copied by Daniell.[57]

- Edward Daniell's last letter is included in Volume II, chapter IX of Edward Forbes and Thomas Spratt's Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis, in company with the Late E. T. Daniell.[66]

- A letter from Daniell's brother-in-law in The Athenæum in 1842 confirmed the artist's death to the public: "The hopes we expressed last week, that there might be some error in the reported death of the Rev. E. T. Daniell, must, we fear, be abandoned ... My attention has been directed to a paragraph in your last number, expressive of surprise at "an announcement in the papers of the death of the Rev. E. T. Daniell" and of "hope that the statement may be an error". I regret to inform you that the announcement is too certainly true; that Mr. Daniell's friends in England are in possession of a letter from Mr. John Purdie, H.B.M.V.-Consul at Adalia, communicating the mournful intelligence of Mr. Daniell's death, at that gentleman's house, on the 24th September last, after a protracted illness of (with intervals of convalescence) more than two months, during which lengthened period of suffering. It is but justice to her majesty's Vice-Consul to say, that all accounts concur in stating that the deceased received from that gentleman the most remitting kindness and attention. I am, &c. Robert Campbell."[68]

- David Wilkie was a British painter who died and was buried at sea, off Gibraltar, returning from his first trip to the Middle East.[80]

- The English artist and poet Edward Lear went on a sketching tour of Egypt and the Holy Land in 1849.[94]

References

- Beecheno 1889, p. 13.

- "Portrait of the Rev Edward Thomas Daniell". The British Museum. 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Hardie 1966, p. 69.

- Cundall 1920, pp. 12, 32.

- Hemingway 2017, pp. 181–182.

- Moore 1985, p. 9.

- Cundall 1920, p. 1.

- Day 1968, p. 7.

- Hemingway 1979, pp. 9, 79.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 10–11.

- Walpole 1997, p. 12.

- Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 3.

- Hemingway 1979, p. 9.

- Clifford 1965, pp. 6–7.

- Clifford 1965, pp. 10–12.

- Moore 1985, p. 12.

- Smail 2004.

- Moore 1985, p. 97.

- Phillimore, Johnson & Bloom 1910.

- John Jun. Holmes in "Bishop's transcripts for the Archdeaconry of Norfolk, 1686–1941", FamilySearch (John Jun. Holmes). Citing Bishop's transcripts for the Archdeaconry of Norfolk, 1686–1941. (registration required)

- "Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries". Morning Post. British Library Newspapers. 24 May 1805. Retrieved 10 July 2020. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries that are in the UK)

- Oliver 1896, pp. 184–186.

- Dickes 1905, p. 546.

- Oliver 1909, p. 177.

- Oliver 1909, p. 225.

- Image 587 in "Baptisms, marriages and burials, 1773–1782", FamilySearch (Image 587). Citing Bishop's transcripts for Yarmouth. (registration required)

- Beecheno 1889, p. 5.

- Mackie 1901, p. 47.

- Oliver 1896, p. 186.

- Beecheno 1889, pp. 5–6.

- Dickes 1905, p. 543.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 1.

-

- "University and Clerical intelligence". The Standard (479). London. 28 November 1828. p. 1. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries that are in the UK)

- Searle 2015, p. 65.

- Searle 2015, p. 113.

- Dickes 1905, p. 544.

- Moore 1985, p. 110.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 2.

- Hamilton 1997, pp. 319–320.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 3.

- Moore 1985, pp. 97–98.

- Searle 2015, p. 64.

- Moore 1985, p. 98.

- White 1845, pp. 178–179.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 16.

- "Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery". Norfolk Museums. 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Dickes 1905, p. 545.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 20.

- Dickes 1905, p. 548.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 4.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 26.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 22.

- Binyon 1899, p. 211.

- Binyon 1899, p. 212.

- Forbes 1842, pp. 1014–1015.

- Hill 1895, p. 116.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 23.

- Forbes & Spratt 1847, p. 214.

- Severis 2000, p. 96.

- Severis 2000, p. 97.

- Dickes 1905, p. 549.

- Binyon 1899, p. 214.

- Forbes & Spratt 1847, p. xv.

- Forbes 1842.

- Forbes & Spratt 1847, p. 36.

- Forbes & Spratt 1847, pp. 1–36.

- "Obituary. The Rev. E. T. Daniell". The Art Journal: 36. 1 February 1843. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Our Weekly Gossip". The Athenæum (786): 993. 19 November 1842. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Hooper 1900, p. 41.

- "Will of Reverend Edward Thomas Daniell, Clerk of Park Street Grosvenor Square, Middlesex". The National Archives. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Dickes 1905, pp. 545–546.

- Story 1892, p. 267.

- Sheldon 2009, pp. 617–618.

- Story 1892, pp. 159, 267–268.

- Beecheno 1889, p. 19.

- Story 1892, p. 268.

- Hamilton 1997, p. 356.

- Story 1892, pp. 269–270.

- Hamilton 1997, p. 319.

- "Sir David Wilkie RA (1785–1841)". RA Collection: People and Organisations. Royal Academy. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 156–157.

- Quiller-Couch 1895, pp. 6–7.

- Clifford 1965, p. 51.

- Searle 2015, p. 67.

- Walpole 1997, p. 159.

- Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 43.

- Walpole 1997, p. 158.

- Geological Society of London 1838, p. 340.

- Graves 1905, p. 241.

- Graves 1895, p. 71.

- Dickes 1905, p. 553.

- Clifford 1965, p. 71.

- Hemingway 1979, p. 70.

- Moore 1985, p. 111.

- Clifford 1965, pp. 51, 71.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 158–159.

- Searle 2015, p. 66.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 6.

- Salaman 1914, pp. 33, 180.

- Searle 2015, p. 106.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, pp. 1, 4.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, pp. 1, 8.

- Searle 2015, pp. 65–69.

- Searle 2015, p. 69.

- Moore 1985, p. 109.

- Searle 2015, p. 68.

- Thistlethwaite 1974, p. 8.

- Daniell & Palgrave 1882.

- "Twelve Etchings by the Rev. E. T. Daniell with a short notice of his life by R. H. Inglis Palgrave". V&A. 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Hardie 1921, p. 15.

- Walpole 1997, p. 1591.

- "Art in Norwich Spring 16 British Art Show Special Edition". Art in Norwich. 2016. p. 47. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "From Norfolk to Nubia The watercolours of E. T. Daniell". East Anglia Art Fund. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Beecheno, Frederick R. (1889). E. T. Daniell: a memoir. Privately printed (Limited edition of 50 copies). OCLC 27318993.

- Binyon, Laurence (1899). "Edward Thomas Daniell, Painter and Etcher". The Dome. London. IV (12). OCLC 665160418. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Clifford, Derek Plint (1965). Watercolours of the Norwich School. London: Cory, Adams & Mackay. OCLC 1624701.

- Cundall, Herbert Minton (1920). Holme, Geoffrey (ed.). The Norwich School. London: Geoffrey Holme Ltd. OCLC 651802612.

- Daniell, Edward Thomas; Palgrave, Robert Harry Inglis (1882). Twelve etchings by the Reverend E. T. Daniell with a short notice of his life by R.H. Inglis Palgrave. Great Yarmouth. OCLC 558920940.

- Day, Harold (1968). East Anglian Painters. II. Eastbourne, UK: Eastbourne Fine Art. ISBN 978-0-902010-10-9.

- Dickes, William Frederick (1905). The Norwich school of painting: being a full account of the Norwich exhibitions, the lives of the painters, the lists of their respecitve exhibits and descriptions of the pictures. Norwich: Jarrold & Sons Ltd. OCLC 558218061.

- Forbes, Edward (26 November 1842). "The Late Rev. E.T. Daniell". The Athenaeum. London (787): 1014–1015. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Forbes, Edward; Spratt, Thomas Abel Brimage (1847). Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis, in company with the Late E. T. Daniell. London: John van Voorst. LCCN 05010095. Volumes 1 and 2

- Geological Society of London (1838). Proceedings of the Geological Society of London, November 1833 to June 1838. 2. London: R. & J.E. Taylor. OCLC 1050830712.

- Graves, Algernon (1905). The Royal Academy of Arts; a complete dictionary of contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. 2. London: H. Graves. OCLC 1066795832.

- Graves, Algernon (1895). A dictionary of artists who have exhibited works in the principal London exhibitions from 1760 to 1893. London: H. Graves. OCLC 758406892.

- Hamilton, James (1997). Turner. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4000-6015-3. (registration required)

- Hardie, Martin (1921). The British school of etching, being a lecture delivered to the Print Collectors' Club. London: Print Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-164-14764-0.

- Hardie, Martin (1966). Water-colour painting in Britain. 2 The Romantic Period. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7134-0717-4. (registration required)

- Hemingway, Andrew (1979). The Norwich School of Painters 1803–1833. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-2001-9.

- Hemingway, Andrew (2017). "Cultural Philanthropy and the Invention of the Norwich School". Landscape between ideology and the aesthetic: Marxist essays on British art and art theory, 1750–1850. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 9-789-00426-900-2.

- Hill, G.F. (1895). "Inscriptions from Lydia and Pisidia copied by Daniell and Fellows". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. London. 15. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Hooper, James (1900). Jarrolds' official illustrated guide to Norwich. London: Jarrold. OCLC 1047500582.

- Mackie, Charles (1901). Norfolk Annals: A Chronological Record of Remarkable Events in the Nineteenth Century. I (1801–1850). Norwich: Norfolk Chronicle. OCLC 17339408.

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. Norwich: HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 978-0-11-701587-6.

- Oliver, Vere Langford (1909). Caribbeana: being miscellaneous papers relating to the history, genealogy, topography, and antiquities of the British West Indies. I. London: Mitchell, Hughes and Clarke. LCCN 09029898.

- Oliver, Vere Langford (1896). The history of the island of Antigua, one of the Leeward Caribbees in the West Indies, from the first settlement in 1635 to the present time. II. London: Mitchell and Hughes. OCLC 908980133.

- Phillimore, W P W; Johnson, Frederic; Bloom, J Harvey (1910). "Norfolk Parish Registers: Marriages". Phillimore's Parish Register Series. London: Phillimore & Co. 2: 105–120. OCLC 504630626.

- Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas (1895). Journals and Correspondence of Lady Eastlake. 1. London: John Murray. OCLC 833587661.

- Rajnai, Miklos; Stevens, Mary (1976). The Norwich Society of Artists, 1805–1833: a dictionary of contributors and their work. Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. ISBN 978-0-903101-29-5.

- Salaman, Malcolm C. (1914). Holme, Charles (ed.). The great painter-etchers from Rembrandt to Whistler. London: The Studio Ltd. LCCN 14002883.

- Searle, Geoffrey R. (2015). Etchings of the Norwich School. Norwich: Lasse Press. ISBN 978-0-95687-589-1.

- Severis, Rita C. (2000). Travelling artists in Cyprus, 1700–1960. London; Wappingers' Falls, New York: Philip Wilson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85-667522-5. (registration required)

- Sheldon, Julie (2009). The Letters of Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake (PDF). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-194-9.

- Smail, Richard (2004). "Daniell, Edward Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. OCLC 56568095. Retrieved 17 December 2018. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries that are in the UK)

- Story, Alfred Thomas (1892). "XVII". The Life of John Linnell. 1. London: Bentley and Son. OCLC 833744497.

- Thistlethwaite, Jane (1974). "The etchings of E. T. Daniell". Norfolk Archaeology. Norwich. 36: 1–22. OCLC 1979600.

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-261-9.

- White, Joseph Blanco (1845). The life of Joseph Blanco White. III. London: J. Chapman. OCLC 225022207.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Thomas Daniell. |

- Works relating to Edward Thomas Daniell in the Norfolk Museums Collections

- Works by Edward Thomas Daniell in the British Museum.

- Works by Edward Thomas Daniell in the Yale Center for British Art

- Parish records for Banham, from 19 October 1832 to 23 March 1834, written by Edward Thomas Daniell: 1832 (image 64 onwards), 1833 (image 60 onwards) and 1834 (image 56 onwards). FamilySearch (registration required)

- Extract of a letter from Edward Daniell to The Athenaeum, describing some of the events of the expedition in Lycia