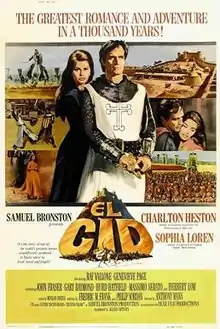

El Cid (film)

El Cid is a 1961 epic historical drama film directed by Anthony Mann and produced by Samuel Bronston. The film is loosely based on the life of the 11th-century Castilian warlord Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, called "El Cid" (from the Arabic as-sidi, meaning "The Lord"). The film stars Charlton Heston in the title role and Sophia Loren as Doña Ximena. The screenplay is credited to Fredric M. Frank, Philip Yordan, and Ben Barzman with uncredited contributions by Bernard Gordon.

| El Cid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Anthony Mann |

| Produced by | Samuel Bronston |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Fredric M. Frank |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Robert Lawrence |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date | December 6, 1961 |

Running time | 184 minutes |

| Country | Italy United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million[1] |

| Box office | $26.6 million[2] |

El Cid premiered on December 6, 1961 at the Metropole Theatre in London, and was released on December 14 in the United States. The film received largely positive reviews praising the performances of Heston and Loren, the cinematography, and the musical score. It went on to gross $26.6 million during its initial theatrical run. It was nominated for three Academy Awards for Best Art Direction, Best Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture, and Best Original Song.

Plot

Gen. Ibn (pronounced Ben) Yusuf (Herbert Lom) of the Almoravid dynasty has summoned all the Emirs of Al-Andalus to North Africa. He chastises them for co-existing peacefully with their Christian neighbors, which goes against his dream of Islamic world domination. The emirs return to Spain with orders to resume hostilities with the Christians while Ibn Yusuf readies his army for a full-scale invasion.

Don Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (Charlton Heston), on the way to his wedding with Doña Ximena (Sophia Loren), rescues a Spanish town from an invading Moorish army. Two of the Emirs, Al-Mu'tamin (Douglas Wilmer) of Zaragoza and Al-Kadir (Frank Thring) of Valencia, are captured. More interested in peace than in wreaking vengeance, Rodrigo escorts his prisoners to Vivar and releases them on condition that they never again attack lands belonging to King Ferdinand of Castile (Ralph Truman). The Emirs proclaim him "El Cid" (the Castillian Spanish pronunciation of the Arabic for Lord: "Al Sidi") and swear allegiance to him.

For his act of mercy, Don Rodrigo is accused of treason by Count Ordóñez (Raf Vallone). In court, the charge is supported by Ximena's father, Count Gormaz (Andrew Cruickshank), the king's champion. Rodrigo's aged father, Don Diego (Michael Hordern), angrily calls Gormaz a liar. Gormaz strikes Don Diego, challenging him to a duel. At a private meeting Rodrigo begs Gormaz to ask the aged but proud Diego for forgiveness (for accusing Rodrigo of treason). Gormaz refuses, so Rodrigo fights the duel on Diego’s behalf and kills his opponent. Ximena witnesses the death of Gormaz and swears to avenge him, renouncing her affection for Rodrigo.

When a rival king demands the city of Calahorra, Rodrigo becomes Ferdinand's champion, winning the city in single combat. In his new capacity he is sent on a mission to collect tribute from Moorish vassals to the Castillian crown. He asks that Ximena be given to him as his wife upon his return, so that he can provide for her. Ximena promises Count Ordóñez she will marry him instead if he kills Rodrigo. Ordóñez lays an ambush for Rodrigo and his men but is captured by Al-Mu'tamin, to whom Rodrigo had earlier showed mercy. Rodrigo forgives the Count and returns home to marry Ximena. The marriage is not consummated: Rodrigo will not touch her if she does not give herself to him out of love. Ximena instead goes to a convent.

King Ferdinand dies and his younger son, Prince Alfonso (John Fraser) tells the elder son Prince Sancho (Gary Raymond) that their father wanted his kingdom divided between his heirs: Castile to Sancho, Asturias and León to Alfonso, and Calahorra to their sister, Princess Urraca (Geneviève Page). Sancho refuses to accept anything but an undivided kingdom as his birthright. After Alfonso instigates a knife fight, Sancho overpowers his brother and sends him to be imprisoned in Zamora. Rodrigo, who swore to protect all the king’s children, singlehandedly defeats Alfonso's guards and brings the Prince to Calahorra. Sancho arrives to demand Alfonso, but Urraca refuses to hand him over. Rodrigo cannot take a side in the conflict, because his oath was to serve them all equally.

Ibn Yusuf arrives at Valencia, the fortified city guarding the beach where he plans to land his armada. To weaken his Spanish opponents he hires Dolfos, a warrior formerly trusted by Ferdinand, to assassinate Sancho and throw suspicion for the crime on Alfonso, who becomes the sole king. At Alfonso's coronation, El Cid has him swear upon the Bible that he had no part in the death of his brother. Alfonso, genuinely innocent, is offended by the demand and banishes Rodrigo from Spain. Ximena discovers she still loves Rodrigo and voluntarily joins him in exile. Rodrigo makes his career as a soldier in foreign lands, and he and Ximena have two children.

Years later, Rodrigo, known widely as "El Cid", is called back into the service of the king to protect Castille from Yusuf's North African army. Rather than work directly with the king El Cid allies himself with the Emirs besieging Valencia, where Al-Kadir has violated his oath of allegiance to Rodrigo and come out in support of Ibn Yusuf.

After being defeated by the Moors, Alfonso seizes Ximena and her children and puts them in prison. Count Ordóñez rescues the three and brings them to Rodrigo, wanting to end his rivalry with El Cid and join him in the defense of Spain. Knowing that the citizens of Valencia are starving after the long siege, Rodrigo wins them over by throwing food into the city with his catapults. Al-Kadir tries to intercede, but the Valencians kill him and open the gates to the besiegers. Emir Al-Mu'tamin, Rodrigo's army, and the Valencians offer the city's crown to El Cid, but he refuses and instead sends the crown to King Alfonso.

Ibn Yusuf arrives with his immense invasion army, and Valencia is the only barrier between him and Spain. The ensuing battle goes well for the defenders until El Cid is struck in the chest by an arrow and has to be carried away to safety. Doctors inform him that they can probably remove the arrow and save his life, but he will be incapacitated for a long time after the surgery. Unwilling to abandon his army at this critical moment, Rodrigo obtains a promise from Ximena to leave the arrow and let him ride back into battle, dying or dead. King Alfonso comes to his bedside and asks for his forgiveness.

Rodrigo dies, and his allies honor his wish to return to the army. With the help of an iron frame they prop up his corpse, dressed in armor and holding a banner, on the back of his horse Babieca. Guided by King Alfonso and Emir Al-Mu'tamin riding on either side, the horse leads a charge against Yusuf's terrified soldiers, who believe that El Cid has risen from the dead. Ibn Yusuf is thrown from his horse and crushed beneath Babieca’s hooves, leaving his scattered army to be annihilated. King Alfonso leads Christians and Moors alike in a prayer for God to receive the soul "of the purest knight of all".

Cast

- Charlton Heston as Don Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, El Cid

- Sophia Loren as Doña Ximena

- Herbert Lom as Ben Yusuf

- Raf Vallone as García Ordóñez

- Geneviève Page as Doña Urraca (sister of Alfonso VI)

- John Fraser as Alfonso VI (King of Castile)

- Douglas Wilmer as Al-Mu'tamin (Emir of Zaragoza)

- Frank Thring as Al-Kadir (Quadir) (Emir of Valencia)

- Michael Hordern as Don Diego (father of Rodrigo)

- Andrew Cruickshank as Count Gormaz (father of Ximena)

- Gary Raymond as Prince Sancho, the 1st born of King Ferdinand

- Ralph Truman as King Ferdinand

- Massimo Serato as Fañez (nephew of Rodrigo)

- Hurd Hatfield, as Arias

- Tullio Carminati as Al-Jarifi

- Fausto Tozzi as Dolfos

- Christopher Rhodes as Don Martín

- Carlo Giustini as Bermúdez

- Gérard Tichy as King Ramiro

- Barbara Everest as Mother Superior

- Katina Noble as Nun

- Nerio Bernardi as Soldier (Credited on film as Nelio Bernardi)

- Franco Fantasia as Soldier

Production

Development

In 1958, producer Samuel Bronston first considered filming El Cid prior to his work on King of Kings (1961), but the production proved to be so troublesome that it would be set aside until King of Kings reached completion.[3] In April 1960, Variety announced that Bronston was independently producing three films in Spain, one of which included El Cid. It was also reported that Bronston had purchased the rights to Fredric M. Frank's 140-page treatment for the film and had hired him the week before to prepare the script by July.[4] In July, Anthony Mann and Philip Yordan had signed on to direct and co-write the film respectively.[5]

However, principal photography was nearly delayed when Cesáreo González's Aspa Films filed an infringement claim against Bronston over the project's title and theme.[6] Previously, in July 1956, it was reported that two biopics of El Cid were in development: an American-Spanish co-production with Anthony Quinn set to star, and a collaboration between RKO, Milton Sperling, and Marvin Gosch.[7] By August 1960, Bronston reached a deal to have Aspa Films and Robert Haggiag's Dear Film involved in the production making the project an American-Italian-Spanish co-production.[6]

Writing

The first writer assigned was Fredric M. Frank. By their mid-November start date, Anthony Mann, Philip Yordan, and Charlton Heston had worked on the script in Madrid, with the first forty pages re-written by Yordan described by Heston as "an improvement over the first draft I'd read".[8] Two days prior to filming, Sophia Loren had read the latest draft in which she became displeased with her dialogue. She then recommended hiring blacklisted screenwriter Ben Barzman to revise the script. Mann subsequently flew out to get Barzman on a plane to Rome in which he gave him a draft, which Barzman found to be unusable.[9] With filming set to begin in a few days, Barzman received a copy of the tragicomedy play Le Cid by Pierre Corneille from the library of the French embassy in Madrid and used it as the basis for a new script. Barzman's screen credit would not be added to the film until 1999.[10][11][9]

However, Barzman's script lacked powerful romantic scenes, which again displeased Loren. Screenwriter Bernard Gordon then stated, "So [Philip] Yordan yanked me from what I was doing in Paris and said, 'Write me three or four love scenes for Loren and Heston.' Well, what the hell – he was paying me $1500 a week, which was a lot more than I made any other way, and I just took orders and I sat down and I wrote four scenes, about three or four pages each. Whatever love scenes there are in the picture I wrote. And they sent them to Loren and said, OK, she'll do the picture, so I was a little bit of a hero at that point."[12][13] Loren had also hired screenwriter Basilio Franchina to translate the dialogue into Italian and then back into simpler English that she felt comfortable with.[14] For script advice and historical truth, Spanish historian Ramón Menéndez Pidal served as the historical consultant to the screenwriters and the director of the film. The naturalist Felix Rodriguez de la Fuente also helped to use raptors and other birds.[15]

Casting

Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren were Bronston's first choices for the two leads.[3] Writing in his autobiography, in the summer of 1960, Heston had received Frank's draft which he described as not "good, ranging from minimally OK to crappy", but he was intrigued with the role. He flew out to Madrid, Spain to meet with Bronston, Yordan, and Mann who all discussed the role with him.[16] On July 26, 1960, his casting was announced.[17] As he conducted research into his role, Heston read El Cantar de mio Cid and arranged a meeting with historian Ramón Menéndez Pidal in Madrid.[18][lower-alpha 1] Initially, Loren was unavailable to portray Ximena, and Jeanne Moreau was briefly considered as a replacement.[3] Another account states Ava Gardner was approached for the role, but she backed out feeling Heston's part was bigger than hers. Mann then suggested his wife Sara Montiel, but Heston and Bronston refused.[19] Ultimately, Loren became available but only for ten to twelve weeks,[3] in which she was paid $200,000; producer Samuel Bronston also agreed to pay $200 a week for her hairdresser.[20][21]

Orson Welles was initially approached to play Ben Yusuf, but he insisted a double do his on-set performance while he would dub in his lines during post-production. Bronston refused.[22] British actors were primarily sought for the other male roles,[22] for which most of the principal casting was completed by early November 1960.[23] That same month, on November 30, Hurd Hatfield had joined the cast.[24] At least four actresses screen-tested for the role for Doña Urraca. Geneviève Page won the part, and her casting was announced on December 16, 1960.[25]

Filming

Principal photography began November 14, 1960 at Sevilla Studios in Madrid, Spain.[26] Filming was reported to spend at least four months of exterior shooting in Spain which would be followed by a final month of interior shooting at the Cinecittà Studios in Rome.[23]

Loren's scenes were shot first as her availability was initially for twelve weeks. Shooting lasted for eight hours a day as the production employed French hours.[27] By January 1961, her part was considerably expanded in response to the early dailies.[1] Simultaneously, second-unit filming for the battle sequences were directed by Yakima Canutt. As filming had progressed, by December 1960, location shooting for action sequences were shot along the Guadarrama Pass. Specifically for the film's second half, Heston suggested growing a gray-flecked beard and wearing a facial scar to showcase Don Rodrigo's battle scarring within the ten-year gap.[28]

With the film's first half nearly complete, shooting for the battle of Valencia was filmed on location in Peñíscola as the actual city had become modernized.[29] For three months, hundreds of production design personnel constructed city walls to block off modern buildings. 1,700 trained infantrymen were leased from the Spanish Army as well as 500 mounted riders from Madrid's Municipal Honor Guard.[30] 15 war machines and siege towers were constructed from historical artwork, and 35 boats were decorated with battlements to serve as the Moorish fleet.[31] Tensions between Mann and Canutt rose as Mann sought to shoot the sequence himself. With the sequence nearly finished, Canutt spent three days filming pick-up shots which would be edited within the longer, master shots that Mann had earlier shot.[32] In his autobiography, Heston expressed his dissatisfaction with Mann's insistence on shooting the battle scenes himself, feeling Canutt was more competent and efficient.[33]

In April 1961, the last sequence to be shot for the film—the duel for Calahorra—was filmed near the Belmonte Castle. The scene was directed by Canutt. Prior to filming, Heston and British actor Christopher Rhodes trained for a month in the use in weaponry under stunt coordinator Enzo Musumeci Greco. The fight took five days to shoot, totaling 31 hours of combat before editing. 70,000 feet of film was shot for the sequence, which was ultimately edited down to 1,080 feet remaining in the film.[34]

Costume design

Costume designers Veniero Colasanti and John Moore oversaw a staff of 400 wardrobe seamstresses which spent roughly $500,000 on manufacturing medieval-style clothing at a local supply company, Casa Cornejo, near Madrid. The most expensive costume piece was a black-and-gold velvet robe worn by King Alfonso VI during the film, which was tailored in Florence, Italy from materials specially woven in Venice. In total, over 2,000 costumes were used for the film.[1][35] For the weaponry, Samuel Bronston Productions sought several local Spanish companies. Casa Cornejo provided 3,000 war helmets and hundreds of iron-studded leather jerkins. The Garrido Brothers factory, located in Toledo, Spain, worked under an exclusive contract for eight months producing 7,000 swords, scimitars, and lances. Anthony Luna, a Madrid prop manufacturer, crafted 40,000 arrows, 5,780 shields, 1,253 medieval harnesses, 800 maces and daggers, 650 suits of chain mail (woven from hemp and coated with a metal varnish), and 500 saddles.[35][1]

Release

The film had its World Premiere at the Metropole Theatre, Victoria, London on December 6th 1961. On December 14, 1961, the film premiered at the Warner Theatre in New York City and premiered at the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles on December 18.[36] For the film's international release, distributors included the Rank Organization releasing the film in Britain, Dear Film in Italy, Astoria Filmes in Portugal, Filmayer in Spain, and Melior in Belgium.[37]

In August 1993, the film was re-released in theaters by Miramax Films having undergone a digital and color restoration supervised by Martin Scorsese. The re-release added 16 minutes of restored footage back to the film's initial 180-minute running time.[38][39]

Home media

The film was released on January 29, 2008 as a deluxe edition and a collector's edition DVD. Both DVDs included bonus materials including archival cast interviews, as well as 1961 promotional radio interviews with Loren and Heston; an audio commentary from Bill Bronston (son of Samuel Bronston) and historian-author Neal M. Rosendorf; a documentary on the importance of film preservation and restoration; biographical featurettes on Samuel Bronston, Anthony Mann, and Miklos Rozsa; and a "making of" documentary, "Hollywood Conquers Spain." The collector's edition DVD also included a reproduction of the premiere's souvenir program and a comic book, as well as six color production stills.[40]

Reception

Box office

The film grossed $26.6 million in the United States and Canada and returned $12 million in rentals (the distributor's share of the box office gross).[2][41]

Contemporary reviews

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote "it is hard to remember a picture--not excluding Henry V, Ivanhoe, Helen of Troy and, naturally, Ben-Hur--in which scenery and regal rites and warfare have been so magnificently assembled and photographed as they are in this dazzler . . . The pure graphic structure of the pictures, the imposing arrangement of the scenes, the dynamic flow of the action against strong backgrounds, all photographed with the 70mm color camera and projected on the Super-Technirama screen, give a grandeur and eloquence to this production that are worth seeing for themselves".[42] Variety praised the film as "a fast-action color-rich, corpse-strewn, battle picture...The Spanish scenery is magnificent, the costumes are vivid, the chain mail and Toledo steel gear impressive."[43] Time felt that "Surprisingly, the picture is good—maybe not as good as Ben-Hur, but anyway better than any spectacle since Spartacus." They also noted that "Bronston's epic has its embarrassments. El Cid himself, too, crudely contemporarized seems less the scourge of the heathen than a champion of civil rights. And there are moments when Hero Heston looks as though he needs a derrick to help him with that broadsword. Nevertheless, Anthony Mann has managed his immense material with firmness, elegance, and a sure sense of burly epic rhythm."[44]

Harrison's Reports praised the performances from Heston and Loren and summarized the film as "raw and strong, brooding and challenging, romantic and powerfully dramatic. It is motion picture entertainment ascending new heights of pomp, pageantry, panoply."[45] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times opened his review writing, "El Cid brings back the excitement of movie-making; it may even bring back the excitement of movie-going. It's as big as Ben-Hur if not bigger. If it had put a few more connectives in the narrative, if it had not thrown in an excess of everything else in three hours running time, it might have been great."[46] Newsweek described the film as being "crammed with jousts and battles, and its sound track is reminiscent of Idlewild airport on a busy day, but the dramatics in it explode with all the force of a panful of popcorn." The reviewer also derided Mann's direction as "slow, stately, and confused, while Miss Loren and Heston spend most of the picture simply glaring at each other."[47]

Sophia Loren had a major issue with Bronston's promotion of the film, an issue important enough to her that Loren sued him for breach of contract in New York Supreme Court. As Time described it:[20]

On a 600-sq.-ft. billboard facing south over Manhattan's Times Square, Sophia Loren's name appears in illuminated letters that could be read from an incoming liner, but—Mamma mia!—that name is below Charlton Heston's. In the language of the complaint: "If the defendants are permitted to place deponent's name below that of Charlton Heston, then it will appear that deponent's status is considered to be inferior to that of Charlton Heston… It is impossible to determine or even to estimate the extent of the damages which the plaintiff will suffer".

Reflective reviews

During its 1993 re-release, Martin Scorsese praised El Cid as "one of the greatest epic films ever made". James Berardinelli of Reel Views gave the film three stars out of four. In his review, he felt that "El Cid turns more often to the ridiculous than the sublime. Perhaps if the movie didn't take itself so seriously, there wouldn't be opportunities for unintentional laughter, but, from the bombastic dialogue to the stentorian score, El Cid is about as self-important as a motion picture can be. Regardless, there are still moments of breathtaking, almost transcendant splendor, when the film makers attain the grand aspirations they strive for.[48] Richard Christiansen for the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four. He commented that "...watching the movie today is something of a chore. Much of its celebration of heroic romanticism seems either sillily inflated or crudely flat in this non-heroic age" and felt Heston and Loren lacked romantic chemistry.[49]

Richard Corliss, reviewing for Time, wrote that "Like the best action films, El Cid is both turbulent and intelligent, with characters who analyze their passions as they eloquently articulate them. The Court scenes, in particular, have the complex intrigue, if not quite the poetry, of a Shakespearean history play. This richness is especially evident in the film's love story."[50] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 92% based on 12 reviews with an average rating of 6.71/10.[51]

Awards and nominations

| Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

| Academy Awards[52] | April 9, 1962 | Best Art Direction | Veniero Colasanti, John Moore | Nominated |

| Best Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture | Miklós Rózsa | |||

| Best Original Song | "Love Theme From El Cid (The Falcon And The Dove)" – Miklós Rózsa and Paul Francis Webster | |||

| Golden Globe Awards[53] | March 5, 1962 | Best Motion Picture – Drama | El Cid | Nominated |

| Best Director | Anthony Mann | |||

| Best Music, Original Score | Miklós Rózsa | |||

| Directors Guild of America[54] | 1962 | Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | Anthony Mann | Nominated |

| British Society of Cinematographers[55] | 1962 | Best Cinematography Award | Robert Krasker | Won |

Comic book adaptation

- Dell Four Color #1259 (1961)[56][57]

See also

- List of American films of 1961

- List of historical drama films

References

- Notes

- In his autobiography, Heston claims he met with Juan Menéndez Pidal, but he had already died in 1915. His brother, Ramón, was still alive in 1960 and as described was in his 90s.

- Citations

- Welles, Benjamin (January 1, 1961). "'REIGN' IN SPAIN; 'El Cid' Is Spectacularly Recreated In Legendary Knight's Homeland". The New York Times.

- Klady, Leonard (February 20, 1995). "Top Grossing Independent Films". Variety. p. A84.

- Allen Smith, Gary (2015). Epic Films: Casts, Credits, and Commentary on More Than 350 Historical Spectacle Movies (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 76. ISBN 978-1476604183.

- Werba, Hank (April 27, 1960). "'Kings' Rolls, 1st of 3 Big Ones for Bronston". Variety. pp. 3, 17. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Scheuer, Philip K. (July 6, 1960). "Bronston Discovers El Cid's Spain". Los Angeles Times. Part II, pg. 9. – via Newspapers.com

- "'Cid's' Near-Skid". Variety. August 31, 1960. p. 5. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "2d 'El Cid' Lined Up with Quinn-Grossman". Variety. July 18, 1956. p. 7 – via Internet Archive.

- Heston 1995, pp. 242–5.

- Martin 2007, pp. 73–5.

- The Making of 'El Cid' (DVD). The Weinstein Company. 2008.

- Barzman 2003, pp. 306–13.

- Martin 2007, pp. 75–6.

- Gordon 1999, p. 122.

- Harris, Warren G. (1998). "Oscar Night". Sophia Loren: A Biography. Simon & Schuster. pp. 161–2. ISBN 978-0684802732.

- "Menéndez Pidal y Rodríguez de la Fuente le ayudaron con "El Cid"". Diario de León. 7 July 2008.

- Heston 1995, pp. 239–41.

- Scheuer, Philip K. (July 26, 1960). "Heston Accepts Lead in 'El Cid'". Los Angeles Times. Part I, pg. 23. – via Newspapers.com

- Heston 1995, p. 245.

- Connolly, Mike (October 19, 1960). "MacDonald Carey on Set For 'Alcatraz'". Valley Times. p. 8. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Egos: Watch My Line". Time. Vol. 79 no. 1. January 5, 1962. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- Connolly, Mike (December 10, 1960). "New Hemingway Picture Planned". Valley Times Today. p. 15. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Heston 1995, p. 244.

- "Mann Winds Casting For Spain Pic, 'El Cid'". Variety. November 2, 1960. p. 11. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "New York Sound Track". Variety. November 30, 1960. p. 17. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "Genevieve Page Set for Role in 'El Cid'". December 16, 1960. Los Angeles Times. Part II, pg. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Heston 1995, p. 248.

- Heston 1995, pp. 248–9.

- Heston 1995, p. 251.

- Heston 1995, p. 253.

- "Spanish Troops Seen in 'El Cid'". March 5, 1962. Los Angeles Times. Part IV, pg. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- Martin 2007, p. 79.

- Canutt & Drake 1979, pp. 198–200.

- Heston 1995, p. 256.

- Martin 2007, p. 78.

- Aberth, John (2012). A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-1135257262.

- "Half-Million in Magazines Heads $2 Million 'Cid' Push". The Monthly Film Bulletin. October 2, 1961. p. 19 – via Internet Archive.

- "'El Cid's' Handlers". Variety. December 28, 1960. p. 13 – via Internet Archive.

- Frook, John Evan (April 16, 1993). "Miramax to rerelease a restored '61 'El Cid'". Variety. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- Hartl, John (August 22, 1993). "Restored 'El Cid,' A Three-Hour Epic, Makes Reappearance". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Arnold, Thomas K. (November 8, 2007). "'El Cid' leads charge for Miriam". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "All-time top film grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 37.

- Crowther, Bosley (December 15, 1961). "Spectacle of 'El Cid' Opens: Epic About a Spanish Hero at the Warner". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- "El Cid (70 M-Super Technirama-Technicolor)". Variety. December 6, 1961. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Cinema: A Round Table of One". Time. Vol. 78 no. 25. December 22, 1961. p. 45. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ""El Cid" with Charlton Heston, Sophia Loren, Raf Vallone, Genevieve Page, John Fraser". Harrison's Reports. Vol. 43 no. 49. December 9, 1961. p. 194. Retrieved March 17, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Scheuer, Philip K (December 10, 1961). "El Cid Flexes Its Muscles ---to the Glory of Moviemaking". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "How To Lose Friends". Newsweek. December 18, 1961. p. 98.

- Berardinelli, James (1993). "El Cid (United States, 1961)". ReelViews.

- Christiansen, Richard (August 27, 1993). "Re-Release 'El Cid' In Losing Battle Against Wooden Acting". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Corliss, Richard (August 6, 2006). "Mann of the Hour". Time. p. 7. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "El Cid (1961)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "The 34th Academy Awards (1962) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Winners & Nominees 1961". Golden Globes. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Directors Guild of America, USA (1961)". IMDb. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "British Society of Cinematographers". IMDb. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Dell Four Color #1259". Grand Comics Database.

- Dell Four Color #1259 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Bibliography

- Barzman, Norma (2003). The Red and the Blacklist: The Intimate Memoir of a Hollywood Expatriate. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1560256175.

- Burt, Richard (2008). Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60125-3.

- Canutt, Yakima; Drake, Oliver (1979). Stunt Man: the Autobiography of Yakima Canutt. Walker and Company. ISBN 0-8027-0613-4.

- Gordon, Bernard (1999). Hollywood Exile: or How I Learned to Love the Blacklist. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292728271.

- Heston, Charlton (1995). In the Arena. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- Martin, Mel (2007). The Magnificent Showman: The Epic Films of Samuel Bronston. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-593931-29-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to El Cid (film). |