Elizabeth Raffald

Elizabeth Raffald (1733 – 19 April 1781) was an English author, innovator and entrepreneur.

Elizabeth Raffald | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Engraving of Elizabeth Raffald, from the 1782 edition of her cookery book | |

| Born | Elizabeth Whitaker 1733 Doncaster, England |

| Died | 19 April 1781 (aged 47–48) Stockport, England |

| Occupation | Housekeeper, businesswoman, author |

| Known for | The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769) |

Born and raised in Doncaster, Yorkshire, Raffald went into domestic service for fifteen years, ending as the housekeeper to the Warburton baronets at Arley Hall, Cheshire. She left her position when she married John, the estate's head gardener. The couple moved to Manchester, Lancashire, where Raffald opened a register office to introduce domestic workers to employers; she also ran a cookery school and sold food from the premises. In 1769 she published her cookery book The Experienced English Housekeeper, which contains the first recipe for a "Bride Cake" that is recognisable as a modern wedding cake. She is also possibly the inventor of the Eccles cake.

In August 1772 Raffald published The Manchester Directory, a listing of 1,505 traders and civic leaders in Manchester—the first such listing for the up-and-coming town. The Raffalds went on to run two important post houses in Manchester and Salford before running into financial problems, possibly brought on by John's heavy drinking. Raffald began a business selling strawberries and hot drinks during the strawberry season. She died suddenly in 1781, just after publishing the third edition of her directory and while still updating the eighth edition of her cookery book.

After her death there were fifteen official editions of her cookery book, and twenty-three pirated ones. Her recipes were heavily plagiarised by other authors, notably by Isabella Beeton in her bestselling Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (1861). Raffald's recipes have been admired by several modern cooks and food writers, including Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson.

Biography

Early life

Raffald was born Elizabeth Whitaker in Doncaster, one of the five daughters of Joshua and Elizabeth Whitaker.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] Raffald was baptised on 8 July 1733. She was given a good schooling, which included learning French.[6] At fifteen she began working in service as a kitchen maid, and rose to the position of housekeeper. Her final post as a domestic servant was at Arley Hall, Cheshire, North West England, where she was housekeeper for Lady Elizabeth Warburton, from the family of the Warburton baronets. Starting work in December 1760, Raffald was paid £16 a year.[7][lower-alpha 2] In all she spent fifteen years in service.[9]

After a few years working for the Warburtons, Elizabeth married John Raffald, the head gardener at Arley Hall.[lower-alpha 3] The ceremony took place on 3 March 1763 at St Mary and All Saints Church, Great Budworth, Cheshire; on 23 April the couple left the Warburtons' service and moved to Fennel Street, Manchester,[1][12] where John's family tended market gardens near the River Irwell.[13] Over the following years, the couple had probably six daughters.[lower-alpha 4] The girls each had their own nurse, and when going out, were dressed in clean white dresses, with the nurses in attendance; at least three of the girls went to boarding schools.[1]

Business career

John opened a floristry shop near Fennel Street; Raffald began an entrepreneurial career at the premises. She rented her spare rooms for storage, began a register office to bring together, for a fee, domestic staff with employers,[17] and advertised that she was "pleased to give her business of supplying cold entertainments, hot French dishes, confectionaries, &c."[18] Over the next few years her business grew, and she added cookery classes to the services she supplied.[17] In August 1766 the Raffalds moved to what was probably a larger premises in Exchange Alley in Market Place.[lower-alpha 5] Here John sold seeds and plants,[1][20] while Raffald, according to her advertisements in the local press, supplied "jellies, creams, possets, flummery, lemon cheese cakes, and all other decorations for cold entertainments; also, Yorkshire hams, tongues, brawn, Newcastle salmon, and sturgeon, pickles, and ketchups of all kinds, lemon pickles";[21] she also supplied the produce for, and organised, civic dinners.[17] The following year, alongside confectionery, she was also selling:

pistachio nuts, French olives, Portugal and French plumbs, prunellos [prunes], limes, preserved pine apples, and all sorts of dry and wet sweetmeats, both foreign and English. Also Turkey figs and other raisins, Jorden and Valencia almonds ... truffles, morels and all sorts of spices.[22]

In 1769 Raffald published her cookery book, The Experienced English Housekeeper, which she dedicated to Lady Warburton.[1][23][lower-alpha 6] As was the practice for publishers at the time, Raffald had obtained subscribers—those who had pre-paid for a copy. The first edition was supported by more than 800 subscribers which raised over £800.[19][25][lower-alpha 7] The subscribers paid five shillings when the book was published; the non-subscribers paid six.[26] The book was "printed by a neighbour whom I can rely on doing it the strictest justice, without the least alteration".[27] The neighbour was Joseph Harrop, who published the Manchester Mercury, a weekly newspaper in which Raffald had advertised extensively.[25][28] She described the book as a "laborious undertaking"[29] that had damaged her health as she had been "too studious and giving too close attention" to it.[29] In an attempt to avoid piracy of her work, Raffald signed the front page of each copy of the first edition.[30]

In the introduction to The Experienced English Housekeeper, Raffald states "I can faithfully assure my friends that ... [the recipes] are wrote from my own experience and not borrowed from any other author".[27] Like her predecessor Hannah Glasse, who wrote The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy in 1747, Raffald did not "gloss ... over with hard names or words of high style, but wrote in ...[her] own plain language".[27] The historian Kate Colquhoun observes that Glasse and Raffald "wrote with an easy confidence", and both were the biggest cookery book sellers in the Georgian era.[31]

In 1771 Raffald released a second edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper, which included a hundred additional recipes.[32] The publisher was Robert Baldwin of 47 Paternoster Row, London, who had paid Raffald £1,400 for the copyright of the book.[33][34][lower-alpha 8] When he asked her to change some of the Mancunian vernacular, she declined, stating "What I have written I proposed to write at the time; it was written deliberately, and I cannot admit of any alteration".[35] Further editions of the book appeared during her lifetime: in 1772 (printed in Dublin), 1773, 1775 and 1776 (all printed in London).[36][lower-alpha 9]

In May 1771 Raffald advertised that she had begun to sell cosmetics from her shop, and listed the availability of distilled lavender water, wash balls, French soap, swan-down powder puffs, tooth powder, lip salve and perfumes.[37] The historian Roy Shipperbottom considers that her nephew—the perfumer to the King of Hanover—was probably the supplier of the items.[14] The same year she also assisted in setting up Prescott's Manchester Journal, the second Mancunian newspaper.[1][30]

.jpg.webp)

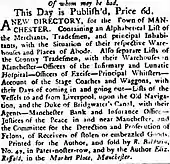

In August 1772 Raffald published The Manchester Directory,[lower-alpha 10] a listing of 1,505 traders and civic leaders in Manchester. She wrote, "The want of a directory for the large and commercial town of Manchester having been frequently complained about ... I have taken on the arduous task of compiling a complete guide".[39] The following year a larger edition followed, also covering Salford.[1][lower-alpha 11]

At some point the Raffalds had also run the Bulls Head tavern—an important post house in the area,[1][15] but in August 1772 the couple took possession of a coaching inn they described as:

the old accustomed and commodious inn, known by the sign of the Kings Head in Salford, Manchester, which they have fitted up in the neatest and most elegant manner, for the reception and accommodation of the nobility, gentry, merchants and tradesmen.[42]

With a large function room at the premises, the Raffalds hosted the annual dinner of the Beefsteak Club and hosted weekly "card assemblies" during the winter season.[34] Cox relates that Raffald's cuisine and her ability to speak French attracted foreign visitors to the inn.[1] Raffald's sister, Mary Whitaker, opened a shop opposite the Kings Head and began selling the same produce Raffald had from the Fennel Street outlet; Mary also restarted the servants' register office.[34]

The couple had problems at the Kings Head. John was drinking heavily and feeling suicidal; when he said he wanted to drown himself, Raffald replied "I do think that it might be the best step you could take, for then you would be relieved of all your troubles and anxieties and you really do harass me very much."[10] Thefts at the inn were common and trade did not flourish; money problems—possibly because they had overstretched themselves with their business dealings over two decades—brought creditors with their demands for repayment. John, as all the financial dealings were in his name, settled the debts by assigning over all the couple's assets and leaving the Kings Head;[43] he was declared bankrupt.[44] They moved back to Market Place in October 1779 where they occupied the Exchange Coffee House. John was made master of the business and Raffald provided food, chiefly soups.[45] During strawberry season she set up a business on the Kersal Moor Racecourse, near the ladies' stand, selling strawberries with cream, tea and coffee.[44][45]

In 1781 the Raffalds' finances improved. Raffald updated The Manchester Directory and a third edition was published; she was compiling the eighth edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper and was writing a book on midwifery with Charles White, the physician and specialist in obstetrics.[1][45] She died suddenly on 19 April 1781 of "spasms, after only one hour's illness";[10] the description is now considered to describe a stroke.[44] The historian Penelope Corfield considers John's bankruptcy may have been a factor in Raffald's early death.[46] She was buried at St Mary's Church, Stockport on 23 April.[10]

A week after Raffald's death, John's creditors took action and he was forced to close the coffee shop and sell off all his assets;[10] initially he attempted to let it as a going concern, but there were no offers, so the lease and all his furniture was handed over to settle the debts.[12] The copyright for the midwifery manuscript seems to have been sold; it is not known if it was ever published, but if it was, Raffald's name did not appear in it.[1] John moved to London soon after Raffald's death and "lived extravagantly", according to Cox. He remarried and returned to Manchester after his money had run out. He reformed on his return, and joined the Wesleyan Methodist Church, where he attended chapel for the next thirty years.[47] He died in December 1809, aged 85 and was buried in Stockport.[43][48]

Works

Cookery

For the first edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper, Raffald had tested all the recipes herself; for the second edition in 1771, she added 100 recipes, some of which she had bought and not tested, but, she informed her readers, she had "weighed them the best I could".[39] Colquhoun considers that the recipes Raffald wrote were those that appealed to Middle England, including "shredded calves' feet, hot chicken pies and carrot puddings, poached eggs on toast, macaroni with parmesan, and lettuce stewed in mint and gravy".[49][50] Raffald was, Colquhoun writes, typical of her time, as she did not want to use garlic, preferred to eat crisp vegetables, and used grated horseradish and cayenne pepper—the last of these Colquhoun describes as "the taste of Empire".[51]

The Experienced English Housekeeper comprises recipes for food and drink only and, unlike many other cookery books of the time, there are no recipes for medicines or perfumes. The work contains one page with instructions for laying the table, and no instructions for servants.[52] More than a third of the recipes in The Experienced English Housekeeper were given over to confectionery, including an early recipe for "Burnt Cream" (crème brûlée), details of how to spin sugar into sugar baskets and instructions of how to create multi-layered jellies, which included in them "fish made from flummery or hen's nests from thinly sliced, syrup poached lemon rind".[53]

The food historian Esther Bradford Aresty considers that "fantasy was Mrs. Raffald's specialty",[54] and cites examples of "A Transparent Pudding Cover'd with a Silver Web, and Globes of Gold with Mottoes in Them", "A Rocky Island", which has peaks of gilded Flummery, a sprig of myrtle decorated with meringue, and a calves-foot jelly sea.[54] Colquhoun thinks some of the recipes are "just a bit bizarre",[49] including the "Rabbit Surprised", where the cook is instructed, after roasting, to "draw out the jaw-bones and stick them in the eyes to appear like horns".[55]

Colquhoun admires Raffald's turn of phrase, such as the advice to reserve water from a raised-pie pastry, as "it makes the crust sad".[56][57] Shipperbottom highlights Raffald's phrases such as "dry salt will candy and shine like diamonds on your bacon",[39][lower-alpha 12] and that wine "summer-beams and blinks in the tub" if barm is not added in time.[39][59]

According to the lexicographer John Ayto, Raffald was the first writer to provide a recipe for crumpets; she provided an early recipe in English cuisine for cooking yams,[60] and an early reference to barbecuing.[61][lower-alpha 13] Ahead of her time, she was a proponent of adding wine to dishes while there was still cooking time left, "to take off the rawness, for nothing can give a made dish a more disagreeable taste than raw wine or fresh anchovy".[56][63]

Directory

Raffald published three editions of The Manchester Directory, in 1772, 1773 and 1781.[1] To compile the listing, she sent "proper and intelligent Persons round the Town, to take down the Name, Business, and place of Abode of every Gentleman, Tradesman, and Shop-keeper, as well as others whose Business or Employment has any tendency to public Notice".[64] The historian Hannah Barker, in her examination of businesswomen in northern England, observes that this process could take weeks or months to complete.[65] The work was divided into two sections: first, a list of the town's traders and the civic elite, in alphabetical order; second, a list of Manchester's major religious, trade, philanthropic and governmental organisations and entities.[66]

Raffald did not list her shop under her own name, but it was recorded under that of her husband, as "John Raffald Seedsman and Confectioner";[38] Barker observes that this was different from Raffald's usual approach, as her shop and book were both advertised under her own name.[67] The Directory contains listings of 94 women in trade—only 6 per cent of the total listings; of those, 46 were listed as widows, which the historian Margaret Hunt considers "a suspiciously large proportion".[68]

Historians have used Raffald's Directory to study the role of women in business in the 18th century.[lower-alpha 14] Barker warns of potential drawbacks with the material, including that only women trading independently of their families, or those who were widowed or single, were likely to be listed, but any woman who traded in partnership with her husband—such as Raffald—would be listed under her husband's name.[73] Hunt points out that there are no keepers of lodging houses listed; directories that cover other towns list significant numbers, but the category is absent from Raffald's work.[38]

Legacy

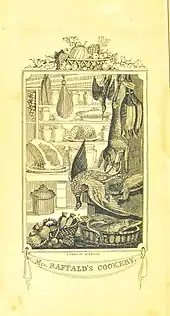

Baldwin brought out the eighth edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper shortly after Raffald died. Throughout her life she had refused to have her portrait painted, but Baldwin included an engraving of her in this edition, wearing a headdress that one of her daughters had made.[43] The Experienced English Housekeeper was a popular book and remained in print for nearly fifty years.[74] Fifteen authorised editions of her book were published and twenty-three pirated ones: the last edition appeared in 1810.[75][76] Along with Hannah Glasse's 1747 work The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy and Eliza Smith's The Compleat Housewife (1727), The Experienced English Housekeeper was one of the cookery books popular in colonial America.[77] Copies had been taken over by travellers and "The Experienced Housekeeper" was printed there.[43]

Raffald's work was plagiarised heavily throughout the rest of the 18th and 19th century; the historian Gilly Lehman writes that Raffald was one of the most copied cookery book writers of the century.[78] Writers who copied Raffald's work include Isabella Beeton, in her bestselling Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (1861);[79] Mary Cole's 1789 work The Lady's Complete Guide;[80] Richard Briggs's 1788 book The English Art of Cookery; The Universal Cook (1773) by John Townshend; Mary Smith's The Complete House-keeper and Professed Cook (1772);[81] and John Farley's 1783 book The London Art of Cookery.[82]

Handwritten copies of individual recipes have been located in family recipe books around England, and Queen Victoria copied several of Raffald's recipes, including one for "King Solomon's Temple in Flummery", when she was a princess.[43]

Ayto states that Raffald was possibly the person who invented the Eccles cake.[83] The food writer Alan Davidson observes that Raffald's recipe—for "sweet patties"—was the basis from which the Eccles cake was later developed.[84] Raffald also played an important role in the development of the wedding cake. Hers was the first recipe for a "Bride Cake" that is recognisable as a modern wedding cake.[85][86] Although cakes had been a traditional part of nuptials, her version differed from previous recipes by the use of what is now called royal icing over a layer of almond paste or icing.[87][88] Simon Charsley, in the Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, considers that Raffald's basis for her cake "became the distinguishing formula for British celebration cakes of increasing variety" over the next century.[89]

Raffald has been admired by several modern cooks and food writers. The 20th-century cookery writer Elizabeth David references Raffald several times in her articles, collected in Is There a Nutmeg in the House,[90] which includes a recipe for apricot ice cream.[91] In her 1984 book, An Omelette and a Glass of Wine, David includes Raffald's recipes for potted ham with chicken, potted salmon, and lemon syllabub.[92] In English Bread and Yeast Cookery (1977), David includes recipes for crumpets, barm pudding, "wegg" (caraway seed cake) and bath buns.[93] The food writer Jane Grigson admired Raffald's work, and in her 1974 book English Food, she included five of Raffald's recipes: bacon and egg pie (a quiche lorraine with a pastry lid); "whet" (anchovy fillets and cheese on toast); potted ham with chicken; crème brûlée; and orange custards.[94]

Raffald is quoted around 270 times in the Oxford English Dictionary,[95] including for the terms "bride cake",[96] "gofer-tongs",[97] "hedgehog soup"[98] and "Hottentot pie".[99] A blue plaque marked the site of the Bulls Head pub which Raffald ran. It was damaged in the 1996 Manchester bombing and replaced in 2011 on the Marks & Spencer Building, Exchange Square.[100][101]

In 2013 Arley Hall introduced some of Raffald's recipes into the menu at the hall's restaurant, which caters for public visitors. Steve Hamilton, Arley Hall's general manager stated that Raffald is "a huge character in Arley's history and it is only right that we mark her contribution to the estate's past". Arley Hall considers Raffald "the Delia Smith of the 18th century".[103][lower-alpha 15]

Notes and references

Notes

- Some sources spell the surname "Whittaker",[3][4] although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the National Portrait Gallery, among others, use Whitaker.[1][5]

- £16 in 1760 equates to around £2,437 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[8]

- John was described by the reporter and antiquary John Harland as being "a very handsome, gentlemanly, intelligent man, about six feet (1.8 m) in height".[10] John, who had been raised in Stockport, Lancashire, had worked at Arley Hall since 1 January 1760 and was on a salary of £20 a year.[11] (£20 in 1760 equates to around £3,046 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[8]

- The sources vary over the number of daughters the Raffalds had. The historian Roy Shipperbottom, who inspected the records of the collegiate church at which Raffald attended, reports that there were six daughters baptised (between March 1766 and September 1774); he says that many of the higher figures quoted came from repeating an unverified source.[14] Nancy Cox, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states the Raffalds had "at least nine" daughters;[1] the food writer Jane Grigson puts the number at fifteen or sixteen;[15] and the historian Eric Quayle says sixteen.[16]

- The historian Hannah Barker, in her examination of businesswomen in northern England, puts the address as 12 Market Place.[19]

- The full title of the work is The Experienced English House-keeper: For the Use and Ease of Ladies, House-Keepers, Cooks, &c.: Wrote Purely from Practice, and Dedicated to the Hon. Lady Elizabeth Warburton, Whom the Author Lately Served as House-keeper: Consisting of Near 800 Original Receipts, Most of Which Never Appeared in Print.[24]

- £800 in 1769 equates to around £112,000 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[8]

- £1,400 in 1769 equates to around £196,000 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[8]

- The 1772 Dublin printing and 1773 London printing are both classed as the second edition.[36]

- The full title of the work was The Manchester Directory for the Year 1772. Containing an Alphabetical List of the Merchants, Tradesmen, and Principal Inhabitants in the Town of Manchester, with the Situation of Their Respective Warehouses, and Places of Abode.[38]

- Lancashire was growing quickly in this period. The population of Salford Hundred, which included Manchester, grew from 96,516 in 1761 to 301,251 in 1801, an average annual growth rate of nearly 3 per cent.[40] Manchester had a population of around 30,000 in 1772.[41]

- Raffald used the phrase when describing how to preserve bacon by using salt.[58]

- The recipe, "To barbicue a pig" took four hours to barbecue a whole ten-week-old pig.[62]

- These include Margaret R. Hunt's The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680–1780 (1996),[69] Hannah Barker's 2006 work The Business of Women: Female Enterprise and Urban Development in Northern England 1760–1830[70] and P. J. Corfield's studies in the Urban History journal.[71][72]

- The American social historian Janet Theophano calls Raffald "the Martha Stewart of her time".[104]

References

- Cox 2004.

- Shipperbottom 1997, p. vii.

- Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 126.

- Quayle 1978, p. 101.

- "Elizabeth Raffald (née Whitaker)". National Portrait Gallery.

- Shipperbottom 1997, pp. vii–viii.

- Cox 2004; Foster 1996, p. 260; Shipperbottom 1997, p. viii.

- Clark 2018.

- Aylett & Ordish 1965, pp. 126–127.

- Harland 1843, p. 149.

- Foster 1996, pp. 258–260, 269.

- Foster 1996, p. 260.

- Shipperbottom 1997, pp. ix, x.

- Shipperbottom 1997, p. xii.

- Grigson 1993, p. 251.

- Quayle 1978, p. 102.

- Shipperbottom 1996, p. 234.

- Raffald 1763, p. 4.

- Barker 2006, p. 76.

- Foster 1996, p. 206.

- Raffald 1766, p. 3.

- Raffald 1767, p. 2.

- Raffald 1769, Dedication page.

- Raffald 1769, Title page.

- Shipperbottom 1996, p. 235.

- Procter 1866, p. 160.

- Raffald 1769, p. i.

- Barker 2006, p. 77.

- Raffald 1769, p. ii.

- Quayle 1978, p. 103.

- Colquhoun 2007, p. 199.

- Raffald 1771b, p. 1; Maclean 2004, p. 121; Shipperbottom 1996, p. 236.

- Quayle 1978, p. 100.

- Shipperbottom 1997, p. xv.

- Harland 1843, p. 147.

- Maclean 2004, p. 121.

- Raffald 1771a, p. 4.

- Hunt 1996, p. 267.

- Shipperbottom 1997, p. xiv.

- Wrigley 2007, p. 66.

- Corfield & Kelly 1984, p. 22.

- Raffald 1772, p. 1.

- Shipperbottom 1997, p. xvi.

- Barker 2006, p. 132.

- Shipperbottom 1996, p. 236.

- Corfield 2012, p. 36.

- Harland 1843, pp. 150–151.

- Harland 1843, p. 151.

- Colquhoun 2007, p. 214.

- (Raffald 1769, pp. 258, 133, 265, 261, 289); recipes cited respectively.

- Colquhoun 2007, pp. 209, 215.

- Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 130.

- Colquhoun 2007, p. 231.

- Aresty 1964, p. 122.

- Raffald 1769, pp. 123–124.

- Colquhoun 2007, p. 215.

- Raffald 1769, p. 125.

- Raffald 1769, p. 285.

- Raffald 1769, p. 317.

- Ayto 1990, pp. 88, 321.

- Miller 2014, p. 142.

- Raffald 1769, p. 99.

- Raffald 1769, p. 70.

- Corfield 2012, p. 26.

- Barker 2006, p. 49.

- Hunt 1996, pp. 130–131.

- Barker 2006, pp. 75–76.

- Hunt 1996, p. 130.

- Hunt 1996, pp. 129–130.

- Barker 2006, pp. 47–50, 75–77, 132–133.

- Corfield 2012, pp. 26, 36.

- Corfield & Kelly 1984, pp. 22, 32.

- Barker 2006, p. 48.

- Colquhoun 2007, p. 213.

- Hardy 2011, p. 95.

- Quayle 1978, p. 104.

- Sherman 2004, pp. 36–37.

- Lehman 2003, 2302.

- Hughes 2006, p. 209.

- Davidson 1983, p. 102.

- Lehman 2003, 22337, 3253.

- Lucraft 1992, p. 7.

- Ayto 1990, p. 130.

- Davidson 2014, p. 273.

- Charsley 1988, pp. 235–236.

- MacGregor 1993, p. 6.

- Wilson 2005, p. 70.

- Charsley 1988, p. 236.

- Charsley 2003, p. 522.

- David 2001, pp. 251, 266.

- David 2001, p. 271.

- David 2014, pp. 222, 225, 235.

- David 1979, pp. 344–345, 420, 433 and 485–487, 480–481.

- (Grigson 1993, pp. 38, 124, 187, 249, 251); recipes cited respectively.

- Brewer 2012, p. 103.

- "bride cake". Oxford English Dictionary.

- "gofer-tongs". Oxford English Dictionary.

- "hedgehog soup". Oxford English Dictionary.

- "Hottentot pie". Oxford English Dictionary.

- "Blue commemorative plaques in Manchester". Manchester City Council.

- "Manchester returns to the tradition of bronze plaques". BBC.

- "The Gardener's Kitchen". Arley Hall & Gardens.

- Theophano 2003, p. 203.

Sources

Books

- Aresty, Esther (1964). The Delectable Past. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 222645438.

- Aylett, Mary; Ordish, Olive (1965). First Catch Your Hare. London: Macdonald. OCLC 54053.

- Ayto, John (1990). The Glutton's Glossary. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4150-2647-5.

- Barker, Hannah (2006). The Business of Women: Female Enterprise and Urban Development in Northern England 1760–1830. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929971-3.

- Charsley, Simon (2003). "Wedding Cake". In Katz, Solomon H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 521–523.

- Colquhoun, Kate (2007). Taste: the Story of Britain Through its Cooking. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-5969-1410-0.

- David, Elizabeth (1979) [1977]. English Bread and Yeast Cookery. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1402-9974-8.

- David, Elizabeth (2001) [2000]. Is There a Nutmeg in the House?. Jill Norman (ed). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-029290-9.

- David, Elizabeth (2014). An Omelette and a Glass of Wine. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1404-6846-5.

- Davidson, Alan (2014). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104072-6.

- Grigson, Jane (1993) [1974]. English Food. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1410-4586-3.

- Hardy, Sheila (2011). The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6122-9.

- Harland, John (1843). Collectanea Relating to Manchester and Its Neighbourhood at Various Periods. 2. Manchester: Chetham Society.

- Hughes, Kathryn (2006). The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton. London: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7524-6122-9.

- Hunt, Margaret R. (1996). The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680–1780. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91694-4.

- Lehman, Gilly (2003). The British Housewife: Cooking and Society in 18th-century Britain (Kindle ed.). Totness, Devon: Prospect Books. ISBN 978-1-909248-00-7.

- MacGregor, Elaine (1993). Wedding Cakes: From Start to Finish. London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63134-2.

- Maclean, Virginia (2004). A Short-Title Catalogue of Household and Cookery Books Published in the English Tongue, 1701–1800. London: Prospect Books. ISBN 978-0-907325-06-2.

- Miller, Tim (2014). Barbecue: a History. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-2753-8.

- Procter, Richard Wright (1866). Manchester in Holiday Dress. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

- Quayle, Eric (1978). Old Cook Books: An Illustrated History. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-289-70707-4.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (1769). The Experienced English House-keeper. Manchester: J. Harrop. OCLC 28369687.

- Sherman, Sandra (2004). Fresh from the Past: Recipes and Revelations from Moll Flanders' Kitchen. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58979-088-9.

- Shipperbottom, Roy (1996). "Elizabeth Raffald (1733–1781)". In Walker, Harlan (ed.). Cooks & Other People: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, 1995. Totnes, Devon: Prospect Books. pp. 233–236. ISBN 978-0-907325-72-7.

- Shipperbottom, Roy (1997). "Introduction". In Raffald, Elizabeth (ed.). The Experienced English Housekeeper. Lewes: Southover Press. ISBN 978-1-870962-13-1.

- Theophano, Janet (2003). Eat My Words: Reading Women's Lives Through the Cookbooks They Wrote. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6293-5.

Journals

- Brewer, Charlotte (February 2012). "'Happy Copiousness'? OED's Recording of Female Authors of the Eighteenth Century". The Review of English Studies. 63 (258): 86–117. doi:10.1093/res/hgq102. JSTOR 41410091.

- Charsley, Simon (January 1988). "The Wedding Cake: History and Meanings". Folklore. 99 (2): 232–241. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1988.9716445. JSTOR 1260461.

- Corfield, Penelope J. (10 January 2012). "Business Leaders and Town Gentry in Early Industrial Britain: Specialist Occupations and Shared Urbanism". Urban History. 39 (1): 20–50. doi:10.1017/S0963926811000769. JSTOR 26398115.

- Corfield, P. J.; Kelly, Serena (9 February 1984). "'Giving Directions to the Town': The Early Town Directories". Urban History. 11: 22–35. doi:10.1017/S0963926800006891. JSTOR 44610004.

- Davidson, Alan (Winter 1983). "Food: The Natural History of British Cookery Books". The American Scholar. 52 (1): 98–106. JSTOR 41210911.

- Foster, Charles (November 1996). "The History of the Gardens at Arley Hall, Cheshire". Garden History. 24 (2): 255–271. doi:10.2307/1587140. JSTOR 1587140.

- Lucraft, Fiona (1992). "The London Art of Plagiarism, Part One". Petits Propos Culinaires. 42: 7–24. ISSN 0142-7857.

- Wilson, Carol (May 2005). "Wedding Cake: A Slice of History". Gastronomica. 5 (2): 69–72. doi:10.1525/gfc.2005.5.2.69.

- Wrigley, E. A. (February 2007). "English County Populations in the Later Eighteenth Century". The Economic History Review. 60 (1): 35–69. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2006.00355.x. JSTOR 4121995. S2CID 153990070.

News

- "Georgian chef Elizabeth Raffald's recipes return to Arley Hall menu". BBC. 6 April 2013.

- "Manchester returns to the tradition of bronze plaques". BBC. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (22 November 1763). "E. Raffald". Manchester Mercury. p. 4.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (14 October 1766). "Elizabeth Raffald". Manchester Mercury. p. 3.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (28 July 1767). "Elizabeth Raffald, Confectioner". Manchester Mercury. p. 2.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (21 May 1771a). "Elizabeth Raffald". Manchester Mercury. p. 4.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (9 August 1771b). "This Day is Published, Price 6s. bound, The Second Edition of that Valuable Work The Experienced English Housekeeper by Elizabeth Raffald". Derby Mercury. p. 1.

- Raffald, Elizabeth (25 August 1772). "John and Elizabeth Raffald". Manchester Mercury. p. 1.

Internet

- "Blue commemorative plaques in Manchester". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "bride cake". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Clark, Gregory (2018). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Cox, Nancy (23 September 2004). "Raffald [née Whitaker], Elizabeth". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Elizabeth Raffald (née Whitaker)". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "The Gardener's Kitchen". Arley Hall & Gardens. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- "gofer-tongs". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "hedgehog soup". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Hottentot pie". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

External links

- Works by or about Elizabeth Raffald at Internet Archive

- Works by Elizabeth Raffald at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)