Elvira Madigan

Hedvig Antoinette Isabella Eleonore Jensen (December 4, 1867 – July 19, 1889), better known by her stage name Elvira Madigan, was a circus performer who performed as a slack rope dancer, artistic rider, juggler and dancer. She is best known today for her romantic relationship with the Swedish nobleman and cavalry officer Sixten Sparre. Their joint death caused great sensation and the event was described in song by, among others, the author Johan Lindström Saxon in a song beginning "Sad things happen", which gained great popularity.[1]

Elvira Madigan | |

|---|---|

Elvira Madigan. | |

| Born | Hedvig Antoinette Isabella Eleonore Jensen December 4, 1867 |

| Died | July 19, 1889 (aged 21) |

| Occupation | Circus performer |

| Parent(s) | Frederik Peter Jensen (father) Eleonora Cecilie Christine Marie Olsen (mother) |

Early life

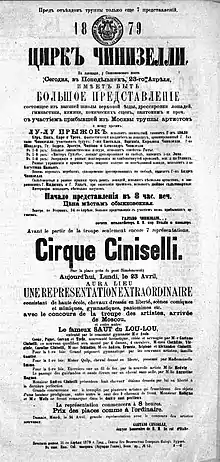

Born Hedvig Antoinette Isabella Eleonore Jensen on December 4, 1867 in Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein in the then Kingdom of Prussia, Elvira Madigan is often said to be Danish, but uncertainty still prevails over which should be considered her home country and about her citizenship.[2][3] Her mother was a circus artist born in Finland but of Norwegian ancestry, Eleonora Cecilie Christine Marie Olsen. She was later known as Laura Madigan (1849–1918) but during Elvira's childhood she mostly used the stage name Miss Ulbinska. The father was circus artist Frederik Peter Jensen, born in 1845 in Copenhagen. His later destiny is unknown. At the time of Elvira Madigan's birth, her parents were not married to each other, and they toured with the French circus director Didier Gautier's "Cirque du Nord" in Germany and Denmark. During the years 1869–1872 Elvira's mother toured with Circus Renz in Germany and Austria, where she in 1871 gave birth to Elvira's half-brother Richard Heinrich Olsen in Berlin. He later toured with the stage name Oscar Madigan. The father of this child is unknown.[4] In 1875, Elvira's mother worked at Circus Myers in Austria,[5] where she got to know the American circus artist John Madigan, whom she subsequently lived with. The following year Elvira Madigan, then still Hedvig Jensen, made her debut in the circus, when she rode a pas-de-deux with John Madigan during a performance with the circus Loisset in Tivoli in Copenhagen . After the death of Loisset in Norrköping the following year, his circus was dissolved, and the Madigan family moved to Circus Ciniselli in Russia. There Elvira Madigan trained to be a slack line dancer.[4]

Career

In the summer of 1879, the Madigan family tried to run their own small circus company in Finland and at the same time Hedvig began using the name Elvira Madigan.[6] The following year, when the family appeared in Circus Cremes in Vienna, Gisela Brož became a foster child in the family, she was two years older than Elvira. Gisela was trained as a tightrope dancer, and together with Elvira on slack line they practiced a unique number, where they appeared simultaneously on separate lines, one above the other. Elvira used to juggle at the same time as she was on the line. The number became a sensation, and in the following years the girls appeared as "daughters of the air" in circuses and in variety rooms across much of Europe, including in Berlin, Paris, London, Brussels and Moscow.[7] After an appearance at Tivoli in Copenhagen in 1886 before the Danish royal family, the girls were each awarded a gold cross by king Kristian IX.[8] The following year, John Madigan again started his own circus company, this time in Denmark. Gisela left the family in the autumn of the same year, after which Elvira had to appear alone when the tour continued to Sweden.

Relationship with Sixten Sparre

In January 1888 circus Madigan appeared in Kristianstad, where Elvira was seen by the dragoon lieutenant Sixten Sparre.[9]

Letter exchange

Sixten Sparre, who was married and had two children, fell madly in love with Elvira, who was considered an extraordinary beauty, with an excellent figure and almost meter-long, blond hair. Sparre sought her out, and the two started a correspondence. Elvira gradually tired of his writing, and several times tried to end their correspondence. Sparre, however, tried to persuade her to leave both her family and the circus to marry him. According to a letter that Elvira's mother later wrote to the Danish newspaper Politiken, Sparre threatened to shoot himself if Elvira did not do as he wanted. He also lied about being divorced from his wife and misled Elvira into believing that he was well off, when in fact he had squandered his entire fortune and was heavily in debt. After a nervous breakdown, Elvira finally gave in, and on May 28, 1889, she secretly left her family at the circus's stop in Sundsvall. The family did not know about Elvira's correspondence with Sparre.[10]

Relationship development

Sparre, who was granted two months leave from May 27, met Elvira in Bollnäs. The two went on to Stockholm, where Elvira's mother made a failed attempt to catch the couple by taking a steamboat from Sundsvall. After a few weeks in an unknown place, they arrived at Svendborg on Funen on June 18. They lived almost a month at the city hotel, but when the hotel director presented a bill, the couple fled. The already heavily indebted Sparre was completely broke at this point, and he and Elvira had obviously lived on credit for several weeks. The two lived a few days in a guest house in Troense on Tåsinge, Denmark. On July 18, they went to the nearby forest area Nørreskov, where Sixten first shot Elvira and then himself on the morning of July 19, 1889. The bodies were only found three days later. In Elvira's dress pocket was found a paper with a poem, which she had written herself just before Sparre killed her with his service revolver.[11] The poem was written in a mixture of Swedish, Danish, Norwegian and German. Interpreted to modern English, it reads:

A drop fell into the water,

faded out slowly.

And the place where it fell

surrounded from wave to wave.

What was it that fell?

and where did it come from?

It was but a life,

and but a death that came

to win itself a track.

- - -

† Now the water rests once again.

Hedvig

Funeral

The couple was buried at Landet's cemetery in the middle of Tåsinge on July 27 in the presence of a large number of locals and summer guests. The hotel bills, funeral costs and tombstones were paid by Sparre's brother Edvard. Elvira's grandmother came to oversee the funeral, but she did not arrive in time.[12] The original tombstones are of two different materials, Elvira's are of white marble and Sixten's of dark gray granite. The difference was to mark that the two were not a "genuine" couple.

The original burial ground is located a few meters south of the great oak in the middle of the cemetery, but during a reorganization of the cemetery walkways in 1943, the gravestones were moved a few meters to the southeast and turned to the west. The original gravestones were replaced by new ones on the 75th anniversary in 1964. At Elvira's new gravestone, her artist name was also mentioned. In 1999, the original tombstones were restored and re-used, but now turned east, while the stones were moved a few meters eastwards. In 2013, the memorial site was redesigned again and the tombstones were placed close to each other in the middle of a circular pavement, located near the 1999 memorial site.[13][14]

Remembrance, re-evaluation of love story

The interpretation of the murder drama that was told was a love story and became to many a symbol of romantic love. It was about a circus princess who was courted by a nobleman, in a combination of morality and entertainment. The event, in its turn, brought a tremendous look, and promptly gave rise to poetry and poems. Saxon's broadside ballad was heard throughout the Nordic countries from the autumn of 1889 and for many decades to come. Everyone knew the story, and everyone could sing the song. But it was not just Barrel organists that conveyed the story, also the newspapers were full of up-to-date descriptions, even with terrible details.[15]

The couple's relationship also gave rise to an intense press debate. The conservative press condemned the couple's actions and Sparre's adultery, while the liberal press was more understanding. The event was interpreted as saying that the couple had to take this step because of the class society of the time and the prevailing sexual morality. Among other things, the Danish author Holger Drachmann wrote the tribute poem "Til de to" (To the two) under these premises. The event was seen as a repetition of the Mayerling incident, but the extent to which the two were influenced by this event is unclear. Already in the first press releases on the drama, this connection to the event in Austria was made six months earlier, and other newspapers continued to spin on this thread, perhaps mostly because this version was what the readers wanted: the all-consuming love, stronger than death, in addition, between a man of noble birth and a woman of very humble lineage (circus performers stood very low on the social scale). This romanticized view of the drama has survived to the present day through movies, novels, musicals and much more.[16]

However, recent years of research give a different picture. It has emerged that Sparre the last few years of his life lived very extravagantly.[17] He had wasted his fortune and systematically withdrew debts in a way that gave rise to questions about his mental health. According to Grönqvist, he may have suffered from bipolar disorder, and his systematic waste, his renunciation of the family and the values his social class traditionally represented (Sparre posed far left politically in the last few years), and finally the love affair with a circus girl should then be seen as the rash of his illness.[18] Lindhe is also condemning in his biography of Sparre's wife Luitgard, but rather sees Sixten as just spoiled, wasteful and narcissistic.

In light of these findings, Sparre's deal with Elvira Madigan appears rather as a classic example of seduction of a basically unwilling girl, whose feelings for Sparre in that case were ambivalent. If Laura Madigan's letter to Politiken[19][20] is considered a reliable source (it is in and of itself a party statement), Sparre forced himself on Elvira via daily love letters, filled with lies about his financial position and his non-existent divorce. Elvira also reacted with a nervous breakdown. When she finally left her family for Sparre, it seems she hoped to marry him and thereby dispel his suicidal thoughts. There is no evidence of Elvira being suicidal; that rather Sparre was driving the suicide decision might be indicated by the content of that poem, "The bridal bouquet", he dedicated to Elvira. Elvira's innermost feelings for Sixten, for obvious reasons, are unknown, but that she would have been deeply in love with him and wanted to die with her Sixten belongs to the romanticized image and has hardly any support in the primary sources.

Elvira Madigan seems to have been shy and withdrawn privately, not the least seductive, despite her favorable appearance and widespread popularity. She was perceived by the time as a dispassionate and a hard flirt (as opposed to the extrovert Gisela), which certainly contributed to her affair with Sixten Sparre raising such a commotion.[21] Elvira supposedly was interested in poetry and literature, and had supposedly been a good amateur pianist.[22] Her mother is alleged to have been overprotective and did not even let her daughter speak to foreign men, but if this had any significance for the course of events is questionable.

Elvira Madigan in culture

In 1943, Åke Ohberg directed the first Swedish film version of Elvira Madigan with Eva Henning and himself in the lead roles. After pressure from relatives of Sixten Sparre, his name was changed to Christian.[23]

In 1967, Bo Widerberg made his film adaptation, Elvira Madigan, with Pia Degermark and Thommy Berggren in the lead roles. The film music used throughout was the second movement from Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major (K. 467) which has since been known as "Elvira Madigan". The same year, Poul Erik Møller Pedersen also directed a Danish film, with Anne Mette Michaelsen in the title role as Elvira Madigan.

In 1990, the "Circus Elvira Madigan" by Jan Wirén and Lars-Åke von Vultée premiered in connection with that year's edition of the Kristianstad Days. Directed by Hasse Alfredson and among others Johan Ulveson was in the cast.

In 1992, the musical Elvira Madigan premiered at Malmö City Theatre, the music was by Nick Bicât and the lead role was played by Kirsti Torhaug. The drama has also been portrayed in several theatre plays, ballets, student speaks, songs and much more. In 2019, a new Elvira Madigan musical was produced in Stockholm, with music by Mette Herlitz to a libretto by Emma Sandanam. A Swedish metal band has also taken the name Elvira Madigan.[24]

The road on which the country church is located was named Elvira Madigans Vej in 1970,[25] and she has also been given the name of a ship, a series of ornaments and much more. Sixten has got a street named after him in the regiment area of Ystad, Sixten Sparres Gata.

See also

References

- Nordisk familjebok, 1951-1955 year edition

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 190–191.

- Enevig. Fakta om Elvira Madigan og Sixten Sparre (in Danish). p. 161.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 17–30.

- Znaimer Wochenblatt 1875-06-26

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 34–37.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 39–51.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 51–60.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 61–73.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 74–103.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 104–135.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 136–148.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 186–187.

- http://www.elvira-madigan.dk/Gravsted/

- Sveriges radio, 19 januari 2015

- Grönqvist. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 174–195.

- Lindhe. Sorgeliga saker hände ... (in Swedish). pp. 180–186.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 77–80.

- Enevig. Fakta om Elvira Madigan og Sixten Sparre (in Danish). pp. 103–114.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 219–221.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 40–41.

- Grönqvist, Klas. En droppe föll... (in Swedish). pp. 189–193.

- Lindhe. Sorgeliga saker hände ... (in Swedish). p. 220.

- https://www.metal-archives.com/bands/Elvira_Madigan/7436

- Enevig. Fakta om Elvira Madigan og Sixten Sparre (in Danish). p. 183.

External links

Media related to Elvira Madigan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elvira Madigan at Wikimedia Commons- http://elviramadigan.se (in Swedish)

- Elvira Madigan at Find a Grave