England in Middle-earth

England and Englishness appear in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden; in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien has often been supposed to have spoken of wishing to create "a mythology for England"; though it seems he never used the actual phrase, commentators have found it appropriate as a description of much of his approach in creating Middle-earth.

Representations of England and Englishness

An English Shire

England and Englishness appear in Middle-earth, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it, including Bree and Tom Bombadil's domain of the Old Forest and the Barrow-downs.[2]

Brian Rosebury likens the Shire to Tolkien's childhood home:[3]

Sarehole, with its nearby farms, its mill by the riverside, its willow-trees, its pool with swans, its dell with blackberries, was a serene quasi-rural enclave, an obvious model-to-be for ... Hobbiton and the Shire.[3]

The Shire is described by Tom Shippey as a calque upon England, a systematic construction mapping the origin of the people, its three original tribes, its two legendary founders, its organisation, its surnames, and its placenames.[1] Others have noted easily perceived aspects such as the homely names of its public houses such as The Green Dragon.[4][5][6] Tolkien stated that he grew up "in 'the Shire' in a pre-mechanical age".[T 1]

| Element | The Shire | England |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of people | The Angle between the Hoarwell and the Loudwater | The Angle between Flensburg Fjord and the Schlei, hence the name "England" |

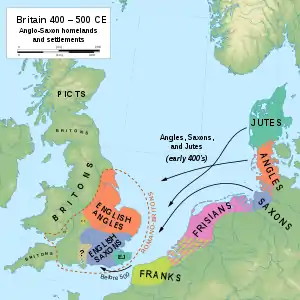

| Original three tribes | Stoors, Harfoots, Fallohides | Angles, Saxons, Jutes[lower-alpha 1] |

| Legendary founders | Marcho and Blanco | Hengest and Horsa (all 4 names meaning "horse")[lower-alpha 2] |

| Length of civil peace | 272 years from Battle of Greenfields to Battle of Bywater | 270 years from Battle of Sedgemoor to publication of Lord of the Rings |

| Organisation | Mayors, moots, Shirriffs | like "an old-fashioned and idealised England" |

| Surnames | e.g. "Took" | Took/Tooke, northern version of English surname "Tuck"[7][lower-alpha 3] |

| Placenames | e.g. "Nobottle" e.g. "Buckland" | Nobottle, Northamptonshire Buckland, Oxfordshire |

Bree and Bombadil are still, in Shippey's words, in "The Little Kingdom", if not quite in the Shire. Bree is similar to the Shire, with hobbits and the welcoming The Prancing Pony inn. Bombadil represents the spirit of place of the Oxfordshire and Berkshire countryside, which Tolkien felt was vanishing.[9][2][T 2]

'English' characters

England appears throughout The Lord of the Rings in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden. Marjorie Burns sees "a Robin Hood touch" in the green-clad Faramir and his men hunting the enemy in Ithilien, while in Fangorn forest, Treebeard's speech "has a comfortable English ring".[2] Treebeard's distinctive booming bass voice with his "hrum, hroom" mannerism is indeed said by Tolkien's biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, to be based directly on that of Tolkien's close friend and fellow Inkling, C. S. Lewis.[10]

_coal_trades_for_last_year%252C_addresses_and_names_of_all_ironmasters%252C_with_a_list_of_blast_furnaces%252C_iron_(14761790294).jpg.webp)

Industrialised England

England appears in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor.[2] In particular, it has been suggested that the industrialized area called "the Black Country" near J. R. R. Tolkien's childhood home inspired his vision of Mordor.[11][12] Shippey further links the fallen wizard Saruman and his industrial Isengard to "Tolkien's own childhood image of industrial ugliness ... Sarehole Mill, with its literally bone-grinding owner".[13]

Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England appears, modified by the people's extensive use of horses in battle, in the land of Rohan. The names of the Rohirrim, the Riders of Rohan, are straightforwardly Old English, as are the terms they use and their placenames: Théoden means "king"; Éored means "troop of cavalry" and Éomer is "horse-famous", both related to Éoh, "horse"; Eorlingas means "sons of Eorl"; Meduseld means "mead-hall". The chapter "The King of the Golden Hall" is constructed to match the passage in the Old English poem Beowulf where the hero approaches the court of Heorot, and many of the names used come directly from there.[14][15][16][T 3]

Old English peoples and monsters

Tolkien regretted that hardly anything was left of English mythology, so that he was forced to look at Norse and other mythologies for guidance. All the same, Shippey writes,[17]

As for creating a 'Mythology for England', one certain fact is that the Old English notions of Elves, Orcs, Ents, Ettens and Woses have through Tolkien been re-released into the popular imagination to join the much more familiar Dwarves ..., Trolls, ... and the wholly-invented Hobbits."[17]

Shakespearean plot elements

Some of the plot elements in The Lord of the Rings resemble Shakespeare's, notably in Macbeth. Tolkien's use of walking trees, the Huorns, to destroy the Orc-horde at the Battle of Helm's Deep carries a definite echo of the coming of Birnam Wood to Dunsinane, though Tolkien admits the mythic nature of the event where Shakespeare denies it. The prophecy that the Lord of the Nazgûl would not die at the hand of any man directly reflects the Macbeth prophecy; commentators have found Tolkien's solution – he is killed by a woman and a hobbit in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields – more satisfying than Shakespeare's (a man brought into the world by Caesarean section, so not exactly "born").[18]

Hobbits as ambassadors of Englishness

Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings. Burns states that[19]

it too lies within the English, in the best of English-kind. It lies in the courage and tenacity Tolkien admired in his fellow countrymen during the First World War; it lies in the English ability to recognize duty and carry resolutely through...

It is the same with the hobbits, who return and rebuild the Shire. Though it is their complacent and comfort-seeking qualities that stand out most consistently, a warrior's courage or an Elf's sensitivity can arise in hobbits as well.[19]

Burns writes that Bilbo Baggins, the eponymous hero of The Hobbit, has acquired or rediscovered "an Englishman's northern roots. He has gained an Anglo-Saxon self-reliance and a Norseman's sense of will, and all of this is kept from excess by a Celtic sensitivity, by a love of earth, of poetry, and of simple song and cheer."[19] She finds a similar balance in the hobbits of The Lord of the Rings, Pippin, Merry, and Sam. Frodo's balance, though, has been destroyed by a quest beyond his strength; he still embodies some of the elements of Englishness, Celtic sorrow and Nordic doom, but lacking the simple cheerfulness of the other hobbits.[19]

'A mythology for England'

Jane Chance Nitzsche's 1979 book Tolkien's Art: A Mythology for England[20] introduced the idea that Tolkien's Middle-earth writings were intended to form "a mythology for England". The concept was reinforced in serious Tolkien scholarship by Shippey's The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (1982, revised 2005).[21][22] In his 2004 chapter "A Mythology for Anglo-Saxon England", Michael Drout states that Tolkien never used the actual phrase, though commentators have found it appropriate as a description of much of his approach in creating Middle-earth. Tolkien wrote in a letter:[23][24]

I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-story – the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendour from the vast backcloths – which I could dedicate simply to: to England; to my country. ... I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched. The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama.

— Letter #131 to Milton Waldman (at Collins), late 1951

Drout comments that scholars broadly agree that Tolkien "succeeded in this project".[24]

Tolkien recognised that England's actual mythology, which he presumed by analogy with Norse mythology, and given the clues that remain, to have existed until Anglo-Saxon times, had been extinguished. Tolkien decided to reconstruct such a mythology, accompanied to some extent by an imagined prehistory or pseudohistory of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes before they migrated to England.[24][25] Michael D. C. Drout analyses in detail and then summarises the imagined prehistory:

The original settlers of Anglo-Saxon England were the sons and descendants of Ælfwine, the Elf-friend who had sailed across the sea to the Holy Isle of the Elves. The prehistory of the descendants of Ælfwine was Tolkien's invented mythology of Arda, but it also included the story of Beowulf, a depiction of the exploits of some others of their ancestors. The early history of Anglo-Saxon England was generated when the half-brothers of Heorrenda, Hengest and Horsa, led the migration of the Jutes from the continent to England. Heorrenda himself composed Beowulf and compiled the legends of Arda in the Golden Book of Heorrenda. Hengest is a character in Beowulf and in Finnsburg. The hero of Beowulf is a Geat, which equals a Goth, one of the continental ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons... It all fits nicely together even though it is probably not true (and Tolkien knew this).[24]

Notes

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- Carpenter (1981), #213 to Deborah Webster, 25 October 1958

- Carpenter (1981), #19 to Stanley Unwin, 16 December 1937

- Two Towers, book 3 ch. 6 "The King of the Golden Hall"

Secondary

- Shippey 2005, pp. 115-118.

- Burns 2005, pp. 26-29.

- Rosebury 2003, p. 134.

- Duriez, Colin (1992). The J.R.R. Tolkien Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to His Life, Writings, and World of Middle-earth. Baker Book House. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-0-8010-3014-7.

- Tyler, J. E. A. (1976). The Tolkien Companion. Macmillan. p. 201.

- Rateliff, John D. (2009). 'A Kind of Elvish Craft': Tolkien as Literary Craftsman. Tolkien Studies. 6. West Virginia University Press. pp. 11ff.

- Shippey 2005, p. 116.

- Reaney & Wilson 1997, pp. 450, 456.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 111-112, 123.

- Carpenter 1977, p. 198.

- Jeffries, Stuart (19 September 2014). "Mordor, he wrote: how the Black Country inspired Tolkien's badlands". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Baratta, Chris (15 November 2011). Environmentalism in the Realm of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-1-4438-3542-8.

- Shippey 2005, p. 194.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 139-145.

- Burns 2005, p. 143.

- Solopova 2009, p. 21.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 350-351.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 205-209.

- Burns 2005, pp. 28-29.

- Chance Nitzsche 1979, Title page and passim.

- Jackson 2015, pp. 22-23.

- Shippey 2005, p. 112.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 345-351.

- Drout 2004, pp. 229-247.

- Cook, Simon J. (2014). "J.R.R. Tolkien's Lost English Mythology". RoundedGlobe. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

Sources

- Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3806-7.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977), J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Chance Nitzsche, Jane (1979). Tolkien's Art: 'A Mythology for England'. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1349046591.

- Drout, Michael D. C. (2004). "A Mythology for Anglo-Saxon England". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth : a Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 229–247. ISBN 978-0-8131-2301-1.

- Jackson, Aaron Isaac (2015). Narrating England: Tolkien, the Twentieth Century, and English Cultural Self-Representation (PDF). Manchester Metropolitan University (PhD thesis).

- Solopova, Elizabeth (2009), Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J.R.R. Tolkien's Fiction, New York City: North Landing Books, ISBN 0-9816607-1-1

- Reaney, P. H.; Wilson, R. M. (1997). A Dictionary of English Surnames. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-198-60092-5.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003). Tolkien : A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1403-91263-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

.jpg.webp)