Environmental hazard

An environmental hazard is a substance, state or event which has the potential to threaten the surrounding natural environment or adversely affect people's health, including pollution and natural disasters such as storms and earthquakes.[1]

It can include any single or combination of toxic chemical, biological, or physical agents in the environment, resulting from human activities or natural processes, that may impact the health of exposed subjects, including pollutants such as heavy metals, pesticides, biological contaminants, toxic waste, industrial and home chemicals.[2]

Human-made hazards while not immediately health-threatening may turn out detrimental to a human's well-being eventually, because deterioration in the environment can produce secondary, unwanted negative effects on the human ecosphere. The effects of water pollution may not be immediately visible because of a sewage system that helps drain off toxic substances. If those substances turn out to be persistent (e.g. persistent organic pollutant), however, they will literally be fed back to their producers via the food chain: plankton -> edible fish -> humans. In that respect, a considerable number of environmental hazards listed below are man-made (anthropogenic) hazards.

Hazards can be categorized in four types:

- Chemical

- Physical (mechanical, etc.)

- Biological

- Psychosocial

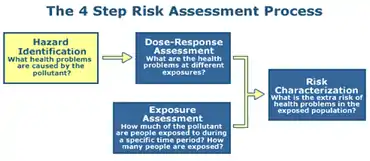

Environmental hazard identification

Environmental hazard identification is the first step in environmental risk assessment, which is the process of assessing the likelihood, or risk, of adverse effects resulting from a given environmental stressor.[3] Hazard identification is the determination of whether, and under what conditions, a given environmental stressor has the potential to cause harm.

In hazard identification, sources of data on the risks associated with prospective hazards are identified. For instance, if a site is known to be contaminated with a variety of industrial pollutants, hazard identification will determine which of these chemicals could result in adverse human health effects, and what effects they could cause. Risk assessors rely on both laboratory (e.g., toxicological) and epidemiological data to make these determinations.[4]

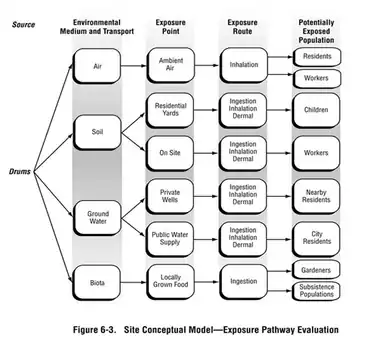

Conceptual model of exposure

Hazards have the potential to cause adverse effects only if they come into contact with populations that may be harmed. For this reason, hazard identification includes the development of a conceptual model of exposure.[5] Conceptual models communicate the pathway connecting sources of a given hazard to the potentially exposed population(s). The U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry establishes five elements that should be included in a conceptual model of exposure:

- The source of the hazard in question

- Environmental fate and transport, or how the hazard moves and changes in the environment after its release

- Exposure point or area, or the place at which an exposed person comes into contact with the hazard

- Exposure route, or the manner by which an exposed person comes into contact with the hazard (e.g., orally, dermally, or by inhalation)

- Potentially exposed populations.[5]

Evaluating hazard data

Once a conceptual model of exposure is developed for a given hazard, measurements should be taken to determine the presence and quantity of the hazard.[6] These measurements should be compared to appropriate reference levels to determine whether a hazard exists. For instance, if arsenic is detected in tap water from a given well, the detected concentrations should be compared with regulatory thresholds for allowable levels of arsenic in drinking water. If the detected levels are consistently lower than these limits, arsenic may not be a chemical of potential concern for the purposes of this risk assessment. When interpreting hazard data, risk assessors must consider the sensitivity of the instrument and method used to take these measurements, including any relevant detection limits (i.e., the lowest level of a given substance that an instrument or method is capable of detecting).[5][6]

Chemical

Chemical hazards are defined in the Globally Harmonized System and in the European Union chemical regulations. They are caused by chemical substances causing significant damage to the environment. The label is particularly applicable towards substances with aquatic toxicity. An example is zinc oxide, a common paint pigment, which is extremely toxic to aquatic life.

Toxicity or other hazards do not imply an environmental hazard, because elimination by sunlight (photolysis), water (hydrolysis) or organisms (biological elimination) neutralizes many reactive or poisonous substances. Persistence towards these elimination mechanisms combined with toxicity gives the substance the ability to do damage in the long term. Also, the lack of immediate human toxicity does not mean the substance is environmentally nonhazardous. For example, tanker truck-sized spills of substances such as milk can cause a lot of damage in the local aquatic ecosystems: the added biological oxygen demand causes rapid eutrophication, leading to anoxic conditions in the water body.

All hazards in this category are mainly anthropogenic although there exist a number of natural carcinogens and chemical elements like radon and lead may turn up in health-critical concentrations in the natural environment:

- Anthrax

- Antibiotic agents in animals destined for human consumption

- Arsenic - a contaminant of fresh water sources (water wells)

- Asbestos - carcinogenic

- DDT

- Carcinogens

- dioxins

- Endocrine disruptors

- Explosive material

- Fungicides

- Furans

- Haloalkanes

- Heavy metals

- Herbicides

- Hormones in animals destined for human consumption

- Lead in paint

- Marine debris

- mercury

- Mutagens

- Pesticides

- Polychlorinated biphenyls

- Radon and other natural sources of radioactivity

- Soil pollution

- Tobacco smoking

- Toxic waste

- Radon

Physical

A physical hazard is a type of occupational hazard that involves environmental hazards that can cause harm with or without contact. Below is a list of examples:

- Cosmic rays

- Drought

- Earthquake

- Electromagnetic fields

- E-waste

- Floods

- Fog

- Light pollution

- Lighting

- Lightning

- Noise pollution

- Quicksand

- Ultraviolet light

- vibration

- X-rays

Biological

Biological hazards, also known as biohazards, refer to biological substances that pose a threat to the health of living organisms, primarily that of humans. This can include medical waste or samples of a microorganism, virus or toxin (from a biological source) that can affect human health. Examples include:

- Allergies

- Arbovirus

- Avian influenza

- Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)

- Cholera

- Ebola

- Epidemics

- Food poisoning

- Malaria

- Molds

- Onchocerciasis (river blindness)

- Pandemics

- Pathogens

- Pollen for allergic people

- Rabies

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

- Sick building syndrome

Psychosocial hazards

Psychosocial hazards include but aren't limited to stress, violence and other workplace stressors. Work is generally beneficial to mental health and personal wellbeing. It provides people with structure and purpose and a sense of identity.

References

- Nursing, health & the environment : strengthening the relationship to improve the public's health. Pope, Andrew MacPherson, 1950-, Snyder, Meta A., Mood, Lillian H., Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Enhancing Environmental Health Content in Nursing Practice. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. 1995. ISBN 0-585-02694-7. OCLC 42329268.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Environmental hazard". Defined Term - A dictionary of legal, industry-specific, and uncommon terms. Retrieved 23 August 2017. quoted from Code of Maryland, January 1, 2014

- US EPA, ORD (2013-09-26). "Risk Assessment". US EPA. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- US EPA, ORD (2014-07-21). "Conducting a Human Health Risk Assessment". US EPA. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- "Chapter 6: Exposure Evaluation: Evaluating Exposure Pathways | PHA Guidance Manual | ATSDR". www.atsdr.cdc.gov. 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- "Chapter 3: Obtaining Site Information | PHA Guidance Manual | ATSDR". www.atsdr.cdc.gov. 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2020-11-03.