Eutrophication

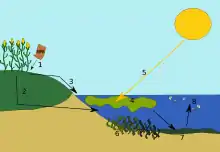

Eutrophication (from Greek eutrophos, "well-nourished"),[1] dystrophication or hypertrophication, is the process by which a body of water becomes overly enriched with minerals and nutrients which induce excessive growth of algae.[2] This process may result in oxygen depletion of the water body after the bacterial degradation of the algae.[3] One example is an "algal bloom" or great increase of phytoplankton in a pond, lake, river or coastal zone as a response to increased levels of nutrients. Eutrophication is often induced by the discharge of nitrate or phosphate-containing detergents, fertilizers, or sewage into an aquatic system.

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Lake eutrophication has become a global problem of water pollution. Chlorophyll-a, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, biological or chemical oxygen demand and secchi depth are the main indicators to evaluate lake eutrophication level.[4] Target 14.1 of sustainable development goal 14 is preventing every form of marine pollution, including nutrient pollution—which is eutrophication.[5]

Mechanism of eutrophication

Eutrophication most commonly arises from the oversupply of nutrients, most commonly as nitrogen or phosphorus, which leads to overgrowth of plants and algae in aquatic ecosystems. After such organisms die, bacterial degradation of their biomass results in oxygen consumption, thereby creating the state of hypoxia.

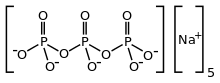

According to Ullmann's Encyclopedia, "the primary limiting factor for eutrophication is phosphate." The availability of phosphorus generally promotes excessive plant growth and decay, favouring simple algae and plankton over other more complicated plants, and causes a severe reduction in water quality. Phosphorus is a necessary nutrient for plants to live, and is the limiting factor for plant growth in many freshwater ecosystems. Phosphate adheres tightly to soil, so it is mainly transported by erosion. Once translocated to lakes, the extraction of phosphate into water is slow, hence the difficulty of reversing the effects of eutrophication.[6] However, numerous literature reports that nitrogen is the primary limiting nutrient for the accumulation of algal biomass.[7]

The sources of these excess phosphates are phosphates in detergent, industrial/domestic run-offs, and fertilizers. With the phasing out of phosphate-containing detergents in the 1970s, industrial/domestic run-off and agriculture have emerged as the dominant contributors to eutrophication.[8]

Cultural eutrophication

Cultural or anthropogenic eutrophication is the process that speeds up natural eutrophication because of human activity.[9] Due to clearing of land and building of towns and cities, land runoff is accelerated and more nutrients such as phosphates and nitrate are supplied to lakes and rivers, and then to coastal estuaries and bays. Extra nutrients are also supplied by treatment plants, golf courses, fertilizers, farms (including fish farms), as well as untreated sewage in many countries.[10]

Lakes and rivers

When algae die, they decompose and the nutrients contained in that organic matter are converted into inorganic form by microorganisms. This decomposition process consumes oxygen, which reduces the concentration of dissolved oxygen. The depleted oxygen levels in turn may lead to fish kills and a range of other effects reducing biodiversity. Nutrients may become concentrated in an anoxic zone and may only be made available again during autumn turn-over or in conditions of turbulent flow. The dead algae and the organic load carried by the water inflows in to the lake settle at its bottom and undergoes anaerobic digestion releasing greenhouse gases such as methane and CO2. Some of the methane gas may be oxidised by anaerobic methane oxidation bacteria such as Methylococcus capsulatus which in turn may provide a food source for zooplankton.[11] Thus a self-sustaining biological process can take place to generate primary food source for the phytoplankton and zooplankton depending on the availability of adequate dissolved oxygen in the water bodies.[12]

Enhanced growth of aquatic vegetation or phytoplankton and algal blooms disrupts normal functioning of the ecosystem, causing a variety of problems such as a lack of oxygen needed for fish and shellfish to survive. Eutrophication also decreases the value of rivers, lakes and aesthetic enjoyment. Health problems can occur where eutrophic conditions interfere with drinking water treatment.[13]

Human activities can accelerate the rate at which nutrients enter ecosystems. Runoff from agriculture and development, pollution from septic systems and sewers, sewage sludge spreading, and other human-related activities increase the flow of both inorganic nutrients and organic substances into ecosystems. Elevated levels of atmospheric compounds of nitrogen can increase nitrogen availability. Phosphorus is often regarded as the main culprit in cases of eutrophication in lakes subjected to "point source" pollution from sewage pipes. The concentration of algae and the trophic state of lakes correspond well to phosphorus levels in water. Studies conducted in the Experimental Lakes Area in Ontario have shown a relationship between the addition of phosphorus and the rate of eutrophication. This is because the growth of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria is reliant on phosphorus concentration levels in lakes.[14] Humankind has increased the rate of phosphorus cycling on Earth by four times, mainly due to agricultural fertilizer production and application. Between 1950 and 1995, an estimated 600,000,000 tonnes of phosphorus was applied to Earth's surface, primarily on croplands.[15]

Natural eutrophication

Although eutrophication is commonly caused by human activities, it can also be a natural process, particularly in lakes. Eutrophy occurs in many lakes in temperate grasslands, for instance. Paleolimnologists now recognise that climate change, geology, and other external influences are critical in regulating the natural productivity of lakes. Some lakes also demonstrate the reverse process (meiotrophication), becoming less nutrient rich with time.[16][17] The main difference between natural and anthropogenic eutrophication is that the natural process is very slow, occurring on geological time scales.[18]

Coastal waters

Eutrophication is a common phenomenon in coastal waters. In contrast to freshwater systems where phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient, nitrogen is more commonly the key limiting nutrient of marine waters; thus, nitrogen levels have greater importance to understanding eutrophication problems in salt water.[19] Estuaries, as the interface between freshwater and saltwater, can be both phosphorus and nitrogen limited and commonly exhibit symptoms of eutrophication. Eutrophication in estuaries often results in bottom water hypoxia/anoxia, leading to fish kills and habitat degradation.[19] Upwelling in coastal systems also promotes increased productivity by conveying deep, nutrient-rich waters to the surface, where the nutrients can be assimilated by algae. Examples of anthropogenic sources of nitrogen-rich pollution to coastal waters include seacage fish farming and discharges of ammonia from the production of coke from coal.

The World Resources Institute has identified 375 hypoxic coastal zones in the world, concentrated in coastal areas in Western Europe, the Eastern and Southern coasts of the US, and East Asia, particularly Japan.[20]

In addition to runoff from land, fish farming wastes and industrial ammonia discharges, atmospheric fixed nitrogen can be an important nutrient source in the open ocean. A study in 2008 found that this could account for around one third of the ocean's external (non-recycled) nitrogen supply, and up to 3% of the annual new marine biological production.[21] It has been suggested that accumulating reactive nitrogen in the environment may prove as serious as putting carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.[22]

Terrestrial ecosystems

Terrestrial ecosystems are subject to similarly adverse impacts from eutrophication.[23] Increased nitrates in soil are frequently undesirable for plants. Many terrestrial plant species are endangered as a result of soil eutrophication, such as the majority of orchid species in Europe.[24] Meadows, forests, and bogs are characterized by low nutrient content and slowly growing species adapted to those levels, so they can be overgrown by faster growing and more competitive species. In meadows, tall grasses that can take advantage of higher nitrogen levels may change the area so that natural species may be lost. Species-rich fens can be overtaken by reed or reedgrass species. Forest undergrowth affected by run-off from a nearby fertilized field can be turned into a nettle and bramble thicket.

Chemical forms of nitrogen are most often of concern with regard to eutrophication, because plants have high nitrogen requirements so that additions of nitrogen compounds will stimulate plant growth. Nitrogen is not readily available in soil because N2, a gaseous form of nitrogen, is very stable and unavailable directly to higher plants. Terrestrial ecosystems rely on microbial nitrogen fixation to convert N2 into other forms such as nitrates. However, there is a limit to how much nitrogen can be utilized. Ecosystems receiving more nitrogen than the plants require are called nitrogen-saturated. Saturated terrestrial ecosystems then can contribute both inorganic and organic nitrogen to freshwater, coastal, and marine eutrophication, where nitrogen is also typically a limiting nutrient.[25] This is also the case with increased levels of phosphorus. However, because phosphorus is generally much less soluble than nitrogen, it is leached from the soil at a much slower rate than nitrogen. Consequently, phosphorus is much more important as a limiting nutrient in aquatic systems.[26]

Ecological effects

Eutrophication was recognized as a water pollution problem in European and North American lakes and reservoirs in the mid-20th century.[27] Since then, it has become more widespread. Surveys showed that 54% of lakes in Asia are eutrophic; in Europe, 53%; in North America, 48%; in South America, 41%; and in Africa, 28%.[28] In South Africa, a study by the CSIR using remote sensing has shown more than 60% of the dams surveyed were eutrophic.[29] Some South African scientists believe that this figure might be higher [30] with the main source being dysfunctional sewage works that produce more than 4 billion liters a day of untreated, or at best partially treated, sewage effluent that discharges into rivers and dams.[31]

Many ecological effects can arise from stimulating primary production, but there are three particularly troubling ecological impacts: decreased biodiversity, changes in species composition and dominance, and toxicity effects.

- Increased biomass of phytoplankton

- Toxic or inedible phytoplankton species

- Increases in blooms of gelatinous zooplankton

- Increased biomass of benthic and epiphytic algae

- Changes in macrophyte species composition and biomass

- Decreases in water transparency (increased turbidity)

- Colour, smell, and water treatment problems

- Dissolved oxygen depletion

- Increased incidences of fish kills

- Loss of desirable fish species

- Reductions in harvestable fish and shellfish

- Decreases in perceived aesthetic value of the water body

Decreased biodiversity

When an ecosystem experiences an increase in nutrients, primary producers reap the benefits first. In aquatic ecosystems, species such as algae experience a population increase (called an algal bloom). Algal blooms limit the sunlight available to bottom-dwelling organisms and cause wide swings in the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water. Oxygen is required by all aerobically respiring plants and animals and it is replenished in daylight by photosynthesizing plants and algae. Under eutrophic conditions, dissolved oxygen greatly increases during the day, but is greatly reduced after dark by the respiring algae and by microorganisms that feed on the increasing mass of dead algae. When dissolved oxygen levels decline to hypoxic levels, fish and other marine animals suffocate. As a result, creatures such as fish, shrimp, and especially immobile bottom dwellers die off.[32] In extreme cases, anaerobic conditions ensue, promoting growth of bacteria. Zones where this occurs are known as dead zones.

New species invasion

Eutrophication may cause competitive release by making abundant a normally limiting nutrient. This process causes shifts in the species composition of ecosystems. For instance, an increase in nitrogen might allow new, competitive species to invade and out-compete original inhabitant species. This has been shown to occur[33] in New England salt marshes. In Europe and Asia, the common carp frequently lives in naturally Eutrophic or Hypereutrophic areas, and is adapted to living in such conditions. The eutrophication of areas outside its natural range partially explain the fish's success in colonising these areas after being introduced.

Toxicity

Some algal blooms resulting from eutrophication, otherwise called "harmful algal blooms", are toxic to plants and animals. Toxic compounds can make their way up the food chain, resulting in animal mortality.[34] Freshwater algal blooms can pose a threat to livestock. When the algae die or are eaten, neuro- and hepatotoxins are released which can kill animals and may pose a threat to humans.[35][36] An example of algal toxins working their way into humans is the case of shellfish poisoning.[37] Biotoxins created during algal blooms are taken up by shellfish (mussels, oysters), leading to these human foods acquiring the toxicity and poisoning humans. Examples include paralytic, neurotoxic, and diarrhoetic shellfish poisoning. Other marine animals can be vectors for such toxins, as in the case of ciguatera, where it is typically a predator fish that accumulates the toxin and then poisons humans.

Sources of high nutrient runoff

Point sources

|

In order to gauge how to best prevent eutrophication from occurring, specific sources that contribute to nutrient loading must be identified. There are two common sources of nutrients and organic matter: point and nonpoint sources.

Point sources

Point sources are directly attributable to one influence. In point sources the nutrient waste travels directly from source to water. Point sources are relatively easy to regulate.

Nonpoint sources

Nonpoint source pollution (also known as 'diffuse' or 'runoff' pollution) is that which comes from ill-defined and diffuse sources. Nonpoint sources are difficult to regulate and usually vary spatially and temporally (with season, precipitation, and other irregular events).

It has been shown that nitrogen transport is correlated with various indices of human activity in watersheds,[38][39] including the amount of development.[33] Ploughing in agriculture and development are activities that contribute most to nutrient loading. There are three reasons that nonpoint sources are especially troublesome:[26]

Soil retention

Nutrients from human activities tend to accumulate in soils and remain there for years. It has been shown[40] that the amount of phosphorus lost to surface waters increases linearly with the amount of phosphorus in the soil. Thus much of the nutrient loading in soil eventually makes its way to water. Nitrogen, similarly, has a turnover time of decades.

Runoff to surface water

Nutrients from human activities tend to travel from land to either surface or ground water. Nitrogen in particular is removed through storm drains, sewage pipes, and other forms of surface runoff. Nutrient losses in runoff and leachate are often associated with agriculture. Modern agriculture often involves the application of nutrients onto fields in order to maximise production. However, farmers frequently apply more nutrients than are taken up by crops[41] or pastures. Regulations aimed at minimising nutrient exports from agriculture are typically far less stringent than those placed on sewage treatment plants[15] and other point source polluters. It should be also noted that lakes within forested land are also under surface runoff influences. Runoff can wash out the mineral nitrogen and phosphorus from detritus and in consequence supply the water bodies leading to slow, natural eutrophication.[42]

Atmospheric deposition

Nitrogen is released into the air because of ammonia volatilization and nitrous oxide production. The combustion of fossil fuels is a large human-initiated contributor to atmospheric nitrogen pollution. Atmospheric nitrogen reaches the ground by two different processes, the first being wet deposition such as rain or snow, and the second being dry deposition which is particles and gases found in the air.[43] Atmospheric deposition (e.g., in the form of acid rain) can also affect nutrient concentration in water,[44] especially in highly industrialized regions.

Other causes

Any factor that causes increased nutrient concentrations can potentially lead to eutrophication. In modeling eutrophication, the rate of water renewal plays a critical role; stagnant water is allowed to collect more nutrients than bodies with replenished water supplies. It has also been shown that the drying of wetlands causes an increase in nutrient concentration and subsequent eutrophication blooms.[45]

Prevention and reversal

Eutrophication poses a problem not only to ecosystems, but to humans as well. Reducing eutrophication should be a key concern when considering future policy, and a sustainable solution for everyone, including farmers and ranchers, seems feasible. While eutrophication does pose problems, humans should be aware that natural runoff (which causes algal blooms in the wild) is common in ecosystems and should thus not reverse nutrient concentrations beyond normal levels. Cleanup measures have been mostly, but not completely, successful. Finnish phosphorus removal measures started in the mid-1970s and have targeted rivers and lakes polluted by industrial and municipal discharges. These efforts have had a 90% removal efficiency.[46] Still, some targeted point sources did not show a decrease in runoff despite reduction efforts.

Shellfish in estuaries: unique solutions

One proposed solution to stop and reverse eutrophication in estuaries is to restore shellfish populations, such as oysters and mussels. Oyster reefs remove nitrogen from the water column and filter out suspended solids, subsequently reducing the likelihood or extent of harmful algal blooms or anoxic conditions.[47] Filter feeding activity is considered beneficial to water quality[48] by controlling phytoplankton density and sequestering nutrients, which can be removed from the system through shellfish harvest, buried in the sediments, or lost through denitrification.[49][50] Foundational work toward the idea of improving marine water quality through shellfish cultivation was conducted by Odd Lindahl et al., using mussels in Sweden.[51] In the United States, shellfish restoration projects have been conducted on the East, West and Gulf coasts.[52] See nutrient pollution for an extended explanation of nutrient remediation using shellfish.

Seaweed farming

Seaweed aquaculture offers an opportunity to mitigate, and adapt to climate change.[53] Seaweed, such as kelp, also absorbs phosphorus and nitrogen[54] and is thus useful to remove excessive nutrients from polluted parts of the sea.[55] Some cultivated seaweeds have a very high productivity and could absorb large quantities of N, P, CO2, producing large amount of O2 have an excellent effect on decreasing eutrophication.[56] It is believed that seaweed cultivation in large scale should be a good solution to the eutrophication problem in coastal waters.

Minimizing nonpoint pollution: future work

Nonpoint pollution is the most difficult source of nutrients to manage. The literature suggests, though, that when these sources are controlled, eutrophication decreases. The following steps are recommended to minimize the amount of pollution that can enter aquatic ecosystems from ambiguous sources.

Riparian buffer zones

Studies show that intercepting non-point pollution between the source and the water is a successful means of prevention.[15] Riparian buffer zones are interfaces between a flowing body of water and land, and have been created near waterways in an attempt to filter pollutants; sediment and nutrients are deposited here instead of in water. Creating buffer zones near farms and roads is another possible way to prevent nutrients from traveling too far. Still, studies have shown[57] that the effects of atmospheric nitrogen pollution can reach far past the buffer zone. This suggests that the most effective means of prevention is from the primary source.

Prevention policy

Laws regulating the discharge and treatment of sewage have led to dramatic nutrient reductions to surrounding ecosystems,[26] but it is generally agreed that a policy regulating agricultural use of fertilizer and animal waste must be imposed. In Japan the amount of nitrogen produced by livestock is adequate to serve the fertilizer needs for the agriculture industry.[58] Thus, it is not unreasonable to command livestock owners to clean up animal waste—which when left stagnant will leach into ground water.

Policy concerning the prevention and reduction of eutrophication can be broken down into four sectors: Technologies, public participation, economic instruments, and cooperation.[59] The term technology is used loosely, referring to a more widespread use of existing methods rather than an appropriation of new technologies. As mentioned before, nonpoint sources of pollution are the primary contributors to eutrophication, and their effects can be easily minimized through common agricultural practices. Reducing the amount of pollutants that reach a watershed can be achieved through the protection of its forest cover, reducing the amount of erosion leeching into a watershed. Also, through the efficient, controlled use of land using sustainable agricultural practices to minimize land degradation, the amount of soil runoff and nitrogen-based fertilizers reaching a watershed can be reduced.[60] Waste disposal technology constitutes another factor in eutrophication prevention. Because a major contributor to the nonpoint source nutrient loading of water bodies is untreated domestic sewage, it is necessary to provide treatment facilities to highly urbanized areas, particularly those in underdeveloped nations, in which treatment of domestic waste water is a scarcity.[61] The technology to safely and efficiently reuse waste water, both from domestic and industrial sources, should be a primary concern for policy regarding eutrophication.

The role of the public is a major factor for the effective prevention of eutrophication. In order for a policy to have any effect, the public must be aware of their contribution to the problem, and ways in which they can reduce their effects. Programs instituted to promote participation in the recycling and elimination of wastes, as well as education on the issue of rational water use are necessary to protect water quality within urbanized areas and adjacent water bodies.

Economic instruments, "which include, among others, property rights, water markets, fiscal and financial instruments, charge systems and liability systems, are gradually becoming a substantive component of the management tool set used for pollution control and water allocation decisions."[59] Incentives for those who practice clean, renewable, water management technologies are an effective means of encouraging pollution prevention. By internalizing the costs associated with the negative effects on the environment, governments are able to encourage a cleaner water management.

Because a body of water can have an effect on a range of people reaching far beyond that of the watershed, cooperation between different organizations is necessary to prevent the intrusion of contaminants that can lead to eutrophication. Agencies ranging from state governments to those of water resource management and non-governmental organizations, going as low as the local population, are responsible for preventing eutrophication of water bodies. In the United States, the most well known inter-state effort to prevent eutrophication is the Chesapeake Bay.[62]

Nitrogen testing and modeling

Soil Nitrogen Testing (N-Testing) is a technique that helps farmers optimize the amount of fertilizer applied to crops. By testing fields with this method, farmers saw a decrease in fertilizer application costs, a decrease in nitrogen lost to surrounding sources, or both.[63] By testing the soil and modeling the bare minimum amount of fertilizer are needed, farmers reap economic benefits while reducing pollution.

Organic farming

There has been a study that found that organically fertilized fields "significantly reduce harmful nitrate leaching" compared to conventionally fertilized fields.[64] However, a more recent study found that eutrophication impacts are in some cases higher from organic production than they are from conventional production.[65]

Geo-engineering in lakes

Geo-engineering is the manipulation of biogeochemical processes, usually the phosphorus cycle, to achieve a desired ecological response in the ecosystem.[66] Geo-engineering techniques typically uses materials able to chemically inactivate the phosphorus available for organisms (i.e. phosphate) in the water column and also block the phosphate release from the sediment (internal loading).[67] Phosphate is one of the main contributing factors to algal growth, mainly cyanobacteria, so once phosphate is reduced the algal is not able to overgrow.[68] Thus, geo-engineering materials is used to speed-up the recovery of eutrophic water bodies and manage algal bloom.[69] There are several phosphate sorbents in the literature, from metal salts (e.g. alum, aluminium sulfate,[70]) minerals, natural clays and local soils, industrial waste products, modified clays (e.g. lanthanum modified bentonite) and others.[71][72] The phosphate sorbent is commonly applied in the surface of the water body and it sinks to the bottom of the lake reducing phosphate, such sorbents have been applied worldwide to manage eutrophication and algal bloom.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

United Nations framework

The United Nations framework for Sustainable Development Goals recognizes the damaging effects of eutrophication upon marine environments and has established a timeline for creating an Index of Coastal Eutrophication and Floating Plastic Debris Density (ICEP).[79] The Sustainable Development Goal 14 specifically has a target to prevent and significantly reduce pollution of all kinds including nutrient pollution (eutrophication) by 2025.[80]

See also

- Algal bloom – Rapid increase or accumulation in the population of planktonic algae

- Anaerobic digestion – Processes by which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen

- Auxanography – The study of the effects of changes in environment on the growth of microorganisms, by means of auxanograms

- Biodilution

- Biogeochemical cycle – Cycling of substances through biotic and abiotic compartments of Earth

- Coastal fish

- Drainage basin – Area of land where precipitation collects and drains off into a common outlet

- Fish kill

- Hypoxia (environmental) – Low environmental oxygen levels

- Hypoxia in fish – Response of fish to environmental hypoxia

- Lake Erie – One of the Great Lakes in North America

- Lake ecosystem

- Limnology – The science of inland aquatic ecosystems

- Nitrogen cycle – Biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into various chemical forms

- No-till farming – Agricultural method which does not disturb soil through tillage.

- Nutrient pollution

- Olszewski tube – A pipe designed to bring oxygen-poor water from the bottom of a lake to the top

- Outwelling – Hypothetical process by which coastal salt marshes and mangroves produce an excess amount of carbon which moves to surrounding areas

- Phoslock

- Residual sodium carbonate index

- Riparian zone – Interface between land and a river or stream

- Soda lake – Lake that is strongly alkaline

- Upland and lowland (freshwater ecology)

References

- "eutrophia", American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fifth ed.), Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2016, retrieved 10 March 2018

- Chislock, M.F.; Doster, E.; Zitomer, R.A.; Wilson, A.E. (2013). "Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences, and Controls in Aquatic Ecosystems". Nature Education Knowledge. 4 (4): 10. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Schindler, David and Vallentyne, John R. (2004) Over fertilization of the World's Freshwaters and Estuaries, University of Alberta Press, p. 1, ISBN 0-88864-484-1

- Du, Huibin; Chen, Zhenni; Mao, Guozhu; Chen, Ling; Crittenden, John; Li, Rita Yi Man; Chai, Lihe (1 July 2019). "Evaluation of eutrophication in freshwater lakes: A new non-equilibrium statistical approach". Ecological Indicators. 102: 686–692. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.03.032.

- "World environment situation room".

- Khan, M. Nasir and Mohammad, F. (2014 ) "Eutrophication of Lakes" in A. A. Ansari, S. S. Gill (eds.), Eutrophication: Challenges and Solutions; Volume II of Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7814-6_1. ISBN 978-94-007-7814-6.

- Khan, Fareed A.; Ansari, Abid Ali (2005). "Eutrophication: An Ecological Vision". Botanical Review. 71 (4): 449–482. doi:10.1663/0006-8101(2005)071[0449:EAEV]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4354503.

- Werner, Wilfried (2002) "Fertilizers, 6. Environmental Aspects". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Biology, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.n10_n05

- Cultural eutrophication (2010) Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 26, 2010, from Encyclopedia Britannica Online:

- Schindler, David W., Vallentyne, John R. (2008). The Algal Bowl: Overfertilization of the World's Freshwaters and Estuaries, University of Alberta Press, ISBN 0-88864-484-1.

- "Climate gases from water bodies". Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "Nature's Value Chain..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Bartram, J., Wayne W. Carmichael, Ingrid Chorus, Gary Jones, and Olav M. Skulberg (1999) Chapter 1. Introduction, in: Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water: A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring and management. World Health Organization. URL: WHO document Archived 2007-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Higgins, Scott N.; Paterson, Michael J.; Hecky, Robert E.; Schindler, David W.; Venkiteswaran, Jason J.; Findlay, David L. (27 November 2017). "Biological Nitrogen Fixation Prevents the Response of a Eutrophic Lake to Reduced Loading of Nitrogen: Evidence from a 46-Year Whole-Lake Experiment". Ecosystems. 21 (6): 1088–1100. doi:10.1007/s10021-017-0204-2. S2CID 26030685.

- Carpenter, S. R.; Caraco, N. F.; Correll, D. L.; Howarth, R. W.; Sharpley, A. N.; Smith, V. H. (August 1998). "Nonpoint Pollution of Surface Waters with Phosphorus and Nitrogen". Ecological Applications. 8 (3): 559. doi:10.2307/2641247. hdl:1813/60811. JSTOR 2641247.

- Walker, I. R. (2006) "Chironomid overview", pp. 360–366 in S.A. EIias (ed.) Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science, Vol. 1, Elsevier,

- Whiteside, M. C. (1983). "The mythical concept of eutrophication". Hydrobiologia. 103: 107–150. doi:10.1007/BF00028437. S2CID 19039247.

- Callisto, Marcos; Molozzi, Joseline and Barbosa, José Lucena Etham (2014) "Eutrophication of Lakes" in A. A. Ansari, S. S. Gill (eds.), Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7814-6_5. ISBN 978-94-007-7814-6.

- Paerl, Hans W.; Valdes, Lexia M.; Joyner, Alan R.; Piehler, Michael F.; Lebo, Martin E. (2004). "Solving problems resulting from solutions: Evolution of a dual nutrient management strategy for the eutrophying Neuse River Estuary, North Carolina". Environmental Science and Technology. 38 (11): 3068–3073. Bibcode:2004EnST...38.3068P. doi:10.1021/es0352350. PMID 15224737.

- Selman, Mindy (2007) Eutrophication: An Overview of Status, Trends, Policies, and Strategies. World Resources Institute.

- Duce, R A; et al. (2008). "Impacts of Atmospheric Anthropogenic Nitrogen on the Open Ocean". Science. 320 (5878): 893–89. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..893D. doi:10.1126/science.1150369. PMID 18487184. S2CID 11204131.

- Addressing the nitrogen cascade Eureka Alert, 2008.

- APIS (2005) Air Pollution Information System.

- Pullin, Andrew S. (2002). Conservation biology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64482-2.

- Hornung M., Sutton M.A. and Wilson R.B. [Eds.] (1995): Mapping and modelling of critical loads for nitrogen — a workshop report. Grange-over-Sands, Cumbria, UK. UN-ECE Convention on Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution, Working Group for Effects, 24–26 October 1994. Published by: Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Edinburgh, UK.

- Smith, V. H.; Tilman, G. D.; Nekola, J. C. (1999). "Eutrophication: Impacts of excess nutrient inputs on freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems". Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987). 100 (1–3): 179–196. doi:10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00091-3. PMID 15093117.

- Rodhe, W. (1969) "Crystallization of eutrophication concepts in North Europe". In: Eutrophication, Causes, Consequences, Correctives. National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C., ISBN 9780309017008 , pp. 50–64.

- ILEC/Lake Biwa Research Institute [Eds]. 1988–1993 Survey of the State of the World's Lakes. Volumes I-IV. International Lake Environment Committee, Otsu and United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- Matthews, Mark; Bernard, Stewart (2015). "Eutrophication and cyanobacteria in South Africa's standing water bodies: A view from space". South African Journal of Science. 111 (5/6). doi:10.17159/sajs.2015/20140193.

- Harding, William R. (2015). "Living with eutrophication in South Africa: A review of realities and challenges". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 70 (2): 155–171. doi:10.1080/0035919X.2015.1014878. S2CID 83523207.

- Turton, Anthony (2015). "Sitting on the Horns of a Dilemma: Water as a Strategic Resource in South Africa". @Liberty. 6 (22): 1–26.

- Horrigan, L.; Lawrence, R. S.; Walker, P. (2002). "How sustainable agriculture can address the environmental and human health harms of industrial agriculture". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (5): 445–456. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110445. PMC 1240832. PMID 12003747.

- Bertness, M. D.; Ewanchuk, P. J.; Silliman, B. R. (2002). "Anthropogenic modification of New England salt marsh landscapes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1395–1398. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1395B. doi:10.1073/pnas.022447299. JSTOR 3057772. PMC 122201. PMID 11818525.

- Anderson D. M. (1994). "Red tides" (PDF). Scientific American. 271 (2): 62–68. Bibcode:1994SciAm.271b..62A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0894-62. PMID 8066432.

- Lawton, L.A.; G.A. Codd (1991). "Cyanobacterial (blue-green algae) toxins and their significance in UK and European waters". Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 40 (4): 87–97. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.1991.tb00643.x.

- Martin, A.; G.D. Cooke (1994). "Health risks in eutrophic water supplies". Lake Line. 14: 24–26.

- Shumway, S. E. (1990). "A Review of the Effects of Algal Blooms on Shellfish and Aquaculture". Journal of the World Aquaculture Society. 21 (2): 65–104. doi:10.1111/j.1749-7345.1990.tb00529.x.

- Cole J.J., B.L. Peierls, N.F. Caraco, and M.L. Pace. (1993) "Nitrogen loading of rivers as a human-driven process", pp. 141–157 in M. J. McDonnell and S.T.A. Pickett (eds.) Humans as components of ecosystems. Springer-Verlag, New York, New York, USA, ISBN 0-387-98243-4.

- Howarth, R. W.; Billen, G.; Swaney, D.; Townsend, A.; Jaworski, N.; Lajtha, K.; Downing, J. A.; Elmgren, R.; Caraco, N.; Jordan, T.; Berendse, F.; Freney, J.; Kudeyarov, V.; Murdoch, P.; Zhao-Liang, Zhu (1996). "Regional nitrogen budgets and riverine inputs of N and P for the drainages to the North Atlantic Ocean: natural and human influences" (PDF). Biogeochemistry. 35: 75–139. doi:10.1007/BF02179825. S2CID 134209808. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-03. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- Sharpley AN, Daniel TC, Sims JT, Pote DH (1996). "Determining environmentally sound soil phosphorus levels". Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 51: 160–166.

- Buol, S. W. (1995). "Sustainability of Soil Use". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 26: 25–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.000325.

- Xie, Meixiang; Zhang, Zhanyu; Zhang, Pingcang (16 January 2020). "Evaluation of Mathematical Models in NitrogenTransfer to Overland Flow Subjectedto Simulated Rainfall". Polish Journal of Environmental Studies. 29 (2): 1421–1434. doi:10.15244/pjoes/106031.

- "Critical Loads – Atmospheric Deposition". U.S Forest Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Paerl H. W. (1997). "Coastal Eutrophication and Harmful Algal Blooms: Importance of Atmospheric Deposition and Groundwater as "New" Nitrogen and Other Nutrient Sources" (PDF). Limnology and Oceanography. 42 (5_part_2): 1154–1165. Bibcode:1997LimOc..42.1154P. doi:10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1154.

- Mungall C. and McLaren, D.J. (1991) Planet under stress: the challenge of global change. Oxford University Press, New York, New York, USA, ISBN 0-19-540731-8.

- Räike, A.; Pietiläinen, O. -P.; Rekolainen, S.; Kauppila, P.; Pitkänen, H.; Niemi, J.; Raateland, A.; Vuorenmaa, J. (2003). "Trends of phosphorus, nitrogen and chlorophyll a concentrations in Finnish rivers and lakes in 1975–2000". Science of the Total Environment. 310 (1–3): 47–59. Bibcode:2003ScTEn.310...47R. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00622-8. PMID 12812730.

- Kroeger, Timm (May 2012). "Dollars and Sense: Economic Benefits and Impacts from two Oyster Reef Restoration Projects in the Northern Gulf of Mexico". The Nature Conservancy.

- Burkholder, JoAnn M. and Sandra E. Shumway. (2011) "Bivalve shellfish aquaculture and eutrophication", in Shellfish Aquaculture and the Environment. Ed. Sandra E. Shumway. John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-8138-1413-8.

- Kaspar, H. F.; Gillespie, P. A.; Boyer, I. C.; MacKenzie, A. L. (1985). "Effects of mussel aquaculture on the nitrogen cycle and benthic communities in Kenepuru Sound, Marlborough Sounds, New Zealand". Marine Biology. 85 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1007/BF00397431. S2CID 83551118.

- Newell, R. I. E.; Cornwell, J. C.; Owens, M. S. (2002). "Influence of simulated bivalve biodeposition and microphytobenthos on sediment nitrogen dynamics: A laboratory study". Limnology and Oceanography. 47 (5): 1367–1379. Bibcode:2002LimOc..47.1367N. doi:10.4319/lo.2002.47.5.1367.

- Lindahl, O.; Hart, R.; Hernroth, B.; Kollberg, S.; Loo, L. O.; Olrog, L.; Rehnstam-Holm, A. S.; Svensson, J.; Svensson, S.; Syversen, U. (2005). "Improving marine water quality by mussel farming: A profitable solution for Swedish society" (PDF). Ambio. 34 (2): 131–138. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.3995. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-34.2.131. PMID 15865310. S2CID 25371433.

- Brumbaugh, R.D. et al. (2006). A Practitioners Guide to the Design and Monitoring of Shellfish Restoration Projects: An Ecosystem Services Approach. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA.

- Duarte, Carlos M.; Wu, Jiaping; Xiao, Xi; Bruhn, Annette; Krause-Jensen, Dorte (12 April 2017). "Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?". Frontiers in Marine Science. 4. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00100.

- Can We Save the Oceans By Farming Them?

- Xiao, X.; Agusti, S.; Lin, F.; Li, K.; Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Duarte, C. M. (2017). "Nutrient removal from Chinese coastal waters by large-scale seaweed aquaculture". Scientific Reports. 7: 46613. Bibcode:2017NatSR...746613X. doi:10.1038/srep46613. PMC 5399451. PMID 28429792.

- Duarte, Carlos M. (2009), "Coastal eutrophication research: a new awareness", Eutrophication in Coastal Ecosystems, Springer Netherlands, pp. 263–269, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3385-7_22, ISBN 978-90-481-3384-0

- Angold P. G. (1997). "The Impact of a Road Upon Adjacent Heathland Vegetation: Effects on Plant Species Composition". The Journal of Applied Ecology. 34 (2): 409–417. doi:10.2307/2404886. JSTOR 2404886.

- Kumazawa, K. (2002). "Nitrogen fertilization and nitrate pollution in groundwater in Japan: Present status and measures for sustainable agriculture". Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 63 (2/3): 129–137. doi:10.1023/A:1021198721003. S2CID 22847510.

- "Planning and Management of Lakes and Reservoirs: An Integrated Approach to Eutrophication." United Nations Environment Programme, Newsletter and Technical Publications. International Environmental Technology Centre. Ch.3.4 (2000).

- Oglesby, R. T.; Edmondson, W. T. (1966). "Control of Eutrophication". Journal (Water Pollution Control Federation). 38 (9): 1452–1460. JSTOR 25035632.

- Middlebrooks, E. J.; Pearson, E. A.; Tunzi, M.; Adinarayana, A.; McGauhey, P. H.; Rohlich, G. A. (1971). "Eutrophication of Surface Water: Lake Tahoe". Journal (Water Pollution Control Federation). 43 (2): 242–251. JSTOR 25036890.

- Nutrient Limitation. Department of Natural Resources, Maryland, U.S.

- Huang, Wen-Yuan; Lu, Yao-chi; Uri, Noel D. (2001). "An assessment of soil nitrogen testing considering the carry-over effect". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 25 (10): 843–860. doi:10.1016/S0307-904X(98)10001-X.

- Kramer, S. B. (2006). "Reduced nitrate leaching and enhanced denitrifier activity and efficiency in organically fertilized soils". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (12): 4522–4527. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.4522K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600359103. PMC 1450204. PMID 16537377.

- Williams, A.G., Audsley, E. and Sandars, D.L. (2006) Determining the environmental burdens and resource use in the production of agricultural and horticultural commodities. Main Report. Defra Research Project IS0205. Bedford: Cranfield University and Defra.

- Spears, Bryan M.; Maberly, Stephen C.; Pan, Gang; MacKay, Ellie; Bruere, Andy; Corker, Nicholas; Douglas, Grant; Egemose, Sara; Hamilton, David; Hatton-Ellis, Tristan; Huser, Brian; Li, Wei; Meis, Sebastian; Moss, Brian; Lürling, Miquel; Phillips, Geoff; Yasseri, Said; Reitzel, Kasper (2014). "Geo-Engineering in Lakes: A Crisis of Confidence?". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (17): 9977–9979. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.9977S. doi:10.1021/es5036267. PMID 25137490.

- MacKay, Eleanor; Maberly, Stephen; Pan, Gang; Reitzel, Kasper; Bruere, Andy; Corker, Nicholas; Douglas, Grant; Egemose, Sara; Hamilton, David; Hatton-Ellis, Tristan; Huser, Brian; Li, Wei; Meis, Sebastian; Moss, Brian; Lürling, Miquel; Phillips, Geoff; Yasseri, Said; Spears, Bryan (2014). "Geoengineering in lakes: Welcome attraction or fatal distraction?". Inland Waters. 4 (4): 349–356. doi:10.5268/IW-4.4.769. hdl:10072/337267. S2CID 55610343.

- Carpenter, S. R. (2008). "Phosphorus control is critical to mitigating eutrophication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (32): 11039–11040. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511039C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806112105. PMC 2516213. PMID 18685114.

- Spears, Bryan M.; Dudley, Bernard; Reitzel, Kasper; Rydin, Emil (2013). "Geo-Engineering in Lakes—A Call for Consensus". Environmental Science & Technology. 47 (9): 3953–3954. Bibcode:2013EnST...47.3953S. doi:10.1021/es401363w. PMID 23611534.

- "Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-28. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- Douglas, G. B.; Hamilton, D. P.; Robb, M. S.; Pan, G.; Spears, B. M.; Lurling, M. (2016). "Guiding principles for the development and application of solid-phase phosphorus adsorbents for freshwater ecosystems" (PDF). Aquatic Ecology. 50 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1007/s10452-016-9575-2. S2CID 18154662.

- Lürling, Miquel; MacKay, Eleanor; Reitzel, Kasper; Spears, Bryan M. (2016). "Editorial – A critical perspective on geo-engineering for eutrophication management in lakes" (PDF). Water Research. 97: 1–10. doi:10.1016/J.WATRES.2016.03.035. PMID 27039034.

- Cooke, G.D., 2005. Restoration and management of lakes and reservoirs. CRC Press.

- Huser, Brian J.; Egemose, Sara; Harper, Harvey; Hupfer, Michael; Jensen, Henning; Pilgrim, Keith M.; Reitzel, Kasper; Rydin, Emil; Futter, Martyn (2016). "Longevity and effectiveness of aluminum addition to reduce sediment phosphorus release and restore lake water quality". Water Research. 97: 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.06.051. PMID 26250754.

- Lürling, Miquel; Oosterhout, Frank van (2013). "Controlling eutrophication by combined bloom precipitation and sediment phosphorus inactivation". Water Research. 47 (17): 6527–6537. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2013.08.019. PMID 24041525.

- Nürnberg, Gertrud K. (2017). "Attempted management of cyanobacteria by Phoslock (Lanthanum-modified clay) in Canadian lakes: Water quality results and predictions". Lake and Reservoir Management. 33 (2): 163–170. doi:10.1080/10402381.2016.1265618. S2CID 89762486.

- Waajen, Guido; Van Oosterhout, Frank; Douglas, Grant; Lürling, Miquel (2016). "Management of eutrophication in Lake de Kuil (The Netherlands) using combined flocculant – Lanthanum modified bentonite treatment". Water Research. 97: 83–95. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.11.034. PMID 26647298.

- Epe, Tim Sebastian; Finsterle, Karin; Yasseri, Said (2017). "Nine years of phosphorus management with lanthanum modified bentonite (Phoslock) in a eutrophic, shallow swimming lake in Germany". Lake and Reservoir Management. 33 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1080/10402381.2016.1263693. S2CID 90314146.

- "14.1.1 Index of Coastal Eutrophication (ICEP) and Floating Plastic debris Density". UN Environment. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Goal 14 targets". UNDP. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

External links

| Look up eutrophication in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |