Eryx (missile)

Eryx is a short-range portable SACLOS-based wire-guided anti-tank missile (ATGM) produced by European company MBDA. It is used by several countries, including the Canadian Army, French, and Norwegian armies. The weapon can also be used against bunkers and pillboxes. It also has some capability in the anti aircraft role to bring down low flying helicopters, due to its wire-guided system. An agreement was reached in 1989 between the French and Canadian governments to co-produce the Eryx missile system.[2] It entered service in 1994.

| Eryx | |

|---|---|

An Eryx deployed on tripod | |

| Type | ATGM |

| Place of origin | France / Canada |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1994 - Current |

| Used by | See users |

| Wars | Yemeni Civil War (2015-present) Saudi-led intervention in Yemen |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1985-92 |

| Manufacturer | MBDA, MKEK (under license) |

| Produced | 1993 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 13.0 kg missile and container; firing post 4.5 kg |

| Length | 0.905 m (2.97 ft) |

| Diameter | 0.136 m (5.4 in) |

| Warhead | 137 mm diameter 3.6 kg tandem HEAT (penetrating 900 mm RHA behind reactive armour,[1] or 2.5 m through concrete) |

Operational range | 50–600 m |

| Maximum speed | 18 m/s (65 km/h) at launch to 245 m/s (880 km/h) at 600 m |

Guidance system | SACLOS wire |

Launch platform | Individual, Vehicle |

Development

The Eryx began as a project in the late 1970s by the French Ministry of defense to replace the short range Luchaire's LRAC F1 STRIM 89mm rocket launcher in the French Army. The requirement was for a cost-effective antitank weapon that could defeat any known or future main battle tank at a maximum range of 600 meters with considerable accuracy, including on windy days. Aérospatiale, the French defense and aerospace firm, believed it was, from a practical standpoint, impossible to design an unguided antitank rocket that could meet the strict requirements. The weapon system that Aérospatiale offered was basically a mini-short range wire guided antitank missile, the ACCP (Anti Char Courte Portée) which in French translates to Short Range Anti-tank Weapon System. The first prototype was delivered to the French Ministry of Defense for testing in 1982. The concept firing post (See: ACCP image) used a scaled-down version of the MILAN tracking and guidance system, but was found in field condition tests to be impractical both from a technical and cost standpoint.[3]

In 1989, France and Canada signed a joint venture to co-produce the ERYX missile. AlliedSignal Aerospace Canada Inc. developed the Mirabel thermal imager for the ERYX firing post.[4] Canadian industries, including Simtran and Solartron Systems, also produced the Eryx Interactive Gunnery Simulator (EVIGS) and the Eryx Precision Gunnery Simulator (EPGS).[5]

Enhanced Eryx

MBDA approached the Canadian government twice, once in 2005, and again in 2006, with a proposal to develop an improved version of the Eryx which would see an improved range, sight, and anti-armour capabilities as a way of extending the Eryx's service life. The Canadian government opted not to participate in the improvement program because it did not meet the new requirements of the Canadian Forces, and conflicted with an ongoing replacement project.[6] In 2007 MBDA provided funding for the development of an enhanced Eryx system. The new system features a new, non-cooled thermal sight which uses a bolometric sensor. MBDA asserts that the new sight is quieter, reduces weight, increases battery life, and provides a detection range greater than the missile's own maximum range. The enhanced Eryx also includes a new training simulator. The system was demonstrated for a potential Middle Eastern customer in October 2009.[7]

Description

The missile is ejected from its launch tube using a very low powered short burn rocket motor located in the tail. The launching motor completes its burn before leaving the container, protecting the gunner from being burned. After the missile coasts a safe distance the main sustainer motor ignites and burns until impacting the target or it reaches its maximum range of 600 meters. The main rocket motor is located at mid-body with two exhausts in the side (e.g. similar to the US BGM-71 TOW antitank missile). Unlike most wire guided antitank missiles the Eryx is propelled at a relative low speed of approximately 240 meters per second at its maximum range. The missile is guided in flight by two vanes located at mid body which act against the main rocket motors thrust. As the missile slowly rotates the launch units send signals commanding the correction by one of the two vanes to move against the missile motors thrust. For example, if the missile has to move to the left, the right thrust vector vane will actuate at the correct time. In addition the "soft launch" is what enables the Eryx to be fired from confined spaces (e.g. buildings) and not cause a massive launch signature that will reveal the Eryx gunners position to hostile counter fire. Aérospatiale claims that this "soft launch" feature enables the Eryx antitank team to be used effectively in urban antitank warfare.[8]

| External images | |

|---|---|

| The ERYX Anti-tank missile | |

The Eryx missile uses a SACLOS guidance system, the launcher tracks a light source on the rear of the missile and compares its position with the center of the launcher's cross-hair, sending corrective signals down a trailing control wire. The missile increases resistance to jamming by having a beacon as the light source on the rear of the missile that pulsates or blinks at a special encoded rate recognized by the Eryx's tracking device located on the launch post. Unlike most wire guides antitank missiles that use SACLOS guidance, which require a complex optical tracker unit that has to zoom from a wide to narrow view in microseconds after the missile is launched (e.g. the MILAN), the Eryx uses one charge-coupled device (CCD) matrix that operate in the IR spectrum, and two fields of view (one narrow and one large) with an automatic switch during missile flight. Again Aérospatiale also states that this unique and simplified SACLOS tracking system provides for a far more cost-effective solution and enable the Eryx to be highly resistant to decoys or jamming and other enemy countermeasures.[8]

The missile uses a tandem-charge HEAT warhead in order to defeat explosive reactive armour fitted to many armored vehicles today; a much smaller-diameter warhead at the front of the missile body and a larger main warhead at the rear. Locating the main warhead at the rear of the missile body provides the correct stand-off needed for the optimum effectiveness of the Eryx warhead without the need of a complex collapsible nose probe (e.g. the TOW), which is standard on most antitank missiles today. This simple solution keeps the missile's cost extremely low when compared to other antitank missiles but also for a compact missile design that can be produced in mass quantities.[8]

Dispute with MBDA and Turkey

In 1998 the Turkish government signed a contract with MBDA to replace the Turkish Armed Forces' aging 3.5-inch rocket launchers and RPG-7s. The deal, worth approximately €404 million, would see the licensed production of 1,600 Eryx launchers, and 20,000 missiles in Turkey. The project encountered setbacks after the Turkish Army claimed that missile failed to meet accuracy requirements of a 72 percent hit rate (i.e. this claim is "unofficially" rejected by MBDA). The poor performance was attributed to technical difficulties, and later corrected by MBDA.[9] In 2004 the Turkish Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (SSM) canceled the contract citing MBDA's failure to meet the terms of the agreement in a timely manner, and MBDA was blacklisted in Turkey. MBDA, in turn, stated that the reason for cancellation was an excuse, and that the systems were simply no longer needed. This is likely based on the 2004 decision by the Turkish Armed Forces to disband four army brigades, and downsize remaining army units, thereby decreasing the requirement for new anti-armor systems. According to MBDA, the ERYX is still in service though with the Turkish Army.[9] The blacklisting has been attributed to a largescale souring of Franco-Turkish relations.[9][10] According to report by Undersecretariat for Defense Industries of Turkey, MBDA and Turkey signed a memorandum of understanding on to acquire 632 Eryx launchers, 3920 missiles and modification systems for a total package of 404m €.[11]

Combat service

With production having begun in 1994, the Eryx had remained untested in live combat until in 2008. While having no notable experience, the Eryx has seen deployment in Afghanistan and UN peace-keeping operations. The Canadian Forces have deployed Eryx to Afghanistan but except for the Mirabel thermal imager, the Eryx missile has never been used in operations.[6] French forces fired the Eryx in Afghanistan, for instance during the battle of Alasay in 2009.[12] In early 2013, pictures emerged of the Eryx being used during the French Army operations in Mali.[13] The Eryx was also fired during Operation Sangaris in Central African Republic in 2013.[14]

During Yemeni Civil War, Eryx has been used by Saudi forces against Houthis.

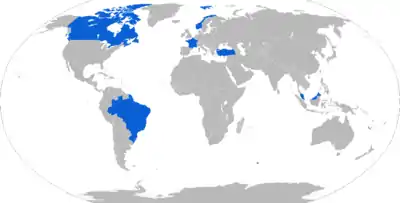

Operators

Current operators

- In service with 10 Paratrooper Brigade only.[16]

References

- Notes

- "Equipment - Canadian Army - ERYX". Department of National Defence. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- Robert Furlong (1990-04-01). "Anti-tank guided missile developments". Armada International. Armada International AG. ISSN 0252-9793. Archived from the original on 2012-10-16. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- Fritz, B. (July 1982). "A Guided Missile As A Short Range Anti-tank Weapon". International Defense Review. Jane's Information Group: 68. ISSN 0020-6512.

- "Eryx". Federation of American scientists. Archived from the original on 2010-02-12.

- "Eryx Heavy Anti-Armour Missile, France". Army-Technology. Archived from the original on 2005-11-25.

- David Pugliese (2009-12-14). "CANADIAN ARMY ERYX MISSILE SYSTEM BEING CANNIBALIZED TO KEEP IT GOING UNTIL 2016". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- "ENHANCED ERYX REGISTERS 100% SUCCESS RATE" (Press release). MBDA. 2009-11-16.

- Nicholas, Nick (Fall 1985). "AEROSPATIALE'S ACCP BRIDGES THE GAP". Combat Weapons. Omega Group Ltd.: 53. ISSN 1052-5076.

- Kemal, Lale (2009-09-06). "Long-standing Eryx missile dispute comes to an end". Sunday's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- Enginsoy, Umit; Ege Bekdil, Burak (2009-10-26). "Turkey Blacklists MBDA Over Missile Dispute".

- "Signed Rockets, Missiles and Munitions Project Agreements". Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (in Turkish). p. 74. Archived from the original (pdf) on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Diner en ville, par le menu". lemamouth.blogspot.com (in French). 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Janes Defense Weekly Vol.50, Issue 10, p 19

- Mariotti, François (Spring 2014). "Considering fire by the perspective of weapon arrays" (PDF). Fantassins. No. 32. pp. 14–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

Opération Sangaris, mai 2014, tir de missiles Eryx durant un accrochage

- Gander, Terry J.; Cutshaw, Charles Q., eds. (2001). Jane's Infantry Weapons 2001/2002 (27th ed.). Coulsdon: Jane's Information Group. ISBN 9780710623171.

- The World Defence Almanac 2005 page 314 ISSN 0722-3226

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Saudi Military use ERYX missile to destroy a Houthi vehicle - YouTube".

- "Eryx Anti-Armour Missile". Army Technology.

- "Aérospatiale vend des missiles Eryx au Canada". Les Échos (in French). 16 June 1993. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Boutilier, Misha; Pasandideh, Shahryar (July 13, 2016). "When it comes to deterring Russia, will Canada's Latvia deployment do the trick?". opencanada.org. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.