Eskimo (film)

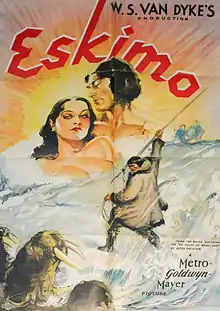

Eskimo (also known as Mala the Magnificent and Eskimo Wife-Traders) is a 1933 American Pre-Code drama film directed by W. S. Van Dyke and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). It is based on the books Der Eskimo and Die Flucht ins weisse Land by Danish explorer and author Peter Freuchen. The film stars Ray Mala as Mala, Lulu Wong Wing as Mala's first wife Aba, Lotus Long as Mala's second wife Iva, Peter Freuchen as the Ship Captain, W. S. Van Dyke as Inspector White, and Joseph Sauers as Sergeant Hunt.

| Eskimo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | W. S. Van Dyke |

| Produced by | Hunt Stromberg W. S. Van Dyke Irving Thalberg |

| Screenplay by | John Lee Mahin |

| Based on | Der Eskimo (1927 book) and Die Flucht ins weisse Land (1929 book) by Peter Freuchen |

| Starring | Ray Mala |

| Music by | William Axt |

| Cinematography | Clyde De Vinna |

| Edited by | Conrad A. Nervig |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 or 120 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English Inupiat |

| Budget | $935,000[1] |

| Box office | $1,312,000[1] |

Eskimo was the first feature film to be shot in a Native American language (Inupiat), although the AFI Catalog of Feature Films lists several earlier features shot in Alaska beginning in the later teens with The Barrier (1917 film), The Girl Alaska (1919), Back to God's Country (1919 film), and Heart of Alaska (1924). Eskimo documented many of the hunting and cultural practices of Native Alaskans. The production for the film was based at Teller, Alaska, where housing, storage facilities, a film laboratory, and other structures were built to house the cast, crew, and equipment.

Eskimo was nicknamed "Camp Hollywood" with a crew that included 42 cameramen and technicians, six airplane pilots, and Emil Ottinger — a chef from the Roosevelt Hotel. Numerous locations were used for filming, including Cape Lisburne in March 1933, Point Hope and Cape Serdtse-Kamen in April to July, and Herald Island in the Chukchi Sea in July. The film crew encountered difficulties recording native speech due to the "kh" sound of the native language. Altogether, pre-production, principal photography, and post-production took 17 months.

The motion picture was well received by critics upon release on November 14, 1933, and received the first-ever Oscar for Best Film Editing, although it didn't fare well at the box office. Scholar Peter Geller has more recently criticized the film as depicting the Eskimo as childlike, simple, and mythic "noble savages" rather than as human beings.

Plot

Mala is a member of an unspecified Eskimo tribe living in Alaska. He has a wife, Aba, and two children. As he and the villagers welcome a hunter from another village, they hunt walrus, and celebrate. Mala learns of white traders at nearby Tjaranak Inlet. He desperately wants rifles, and Aba longs for sewing needles and other white men's goods. Mala and Aba travel by dog sled to the trading ship with their children, and encounter an old friend whose wife died about a month before. Mala offers his friend to have sex with a willing Aba, which comforts their friend, and they part ways contentedly. When they meet the white ship captain, he exchanges Mala's tanned animal skins for a rifle. The captain demands that Aba spend the night with him and gets her drunk, and has sex with her. Mala demands that the captain promises him that Aba will not be molested again.

Mala and the Eskimos go bowhead whale hunting in wooden boats with harpoons, and an actual whale hunt and carcass butchering is depicted. After the successful hunt, two drunken white men kidnap Aba and the ship captain rapes her. Aba staggers away still drunk at dawn. The Captain's Mate disgusted by the captain's betrayal, is hunting seals. He mistakes Aba for an animal and kills her. Mala kills the ship's captain with a harpoon, mistakenly believing the captain shot his wife. He flees to his village.

Lonely and needing someone to care for his children, Mala asks the hunter if his wife Iva can help with sewing hides. Mala still longs for Aba, and, though Iva moves in with him, their relationship is cold. The Eskimos go hunting caribou by stampeding the animals into a lake and shooting them with bow and arrow and spears. Mala is haunted by Aba's death, and after pouring out his grief through dance and prayer, he changes his name to Kripik. Kripik's attitude toward Iva softens dramatically, and they make love. The hunter whom Mala befriended decides to return to his village and gives Kripik his other wife in gratitude, who is delighted to live with Iva and Mala.

Many years pass. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police[lower-alpha 1] establishes a post at Tjaranak, bringing law to the area. Several white men accuse the Eskimos of being savage and without morals and charge Mala with the murder of the ship's captain. Sergeant Hunt and Constable Balk try to find Mala and arrest him but nearly freeze to death in a blizzard. Kripik saves their lives and is hostile toward the men until Hunt explains that they do not want Kripik's wives. The Mounties believe Mala is dead, but Akat arrives in the village and unintentionally exposes Kripik.

The Mounties convince Kripik to answer questions, and several months pass. Hunt and Balk give Kripik freedom, but Hunt learns about the horrors the white traders committed on the Eskimo. When the Eskimo village moves to new hunting rounds, Kripik's family stays behind. They starve, and Kripik learns of their plight. However, the rigid and rule-bound Inspector White has arrived at the RCMP outpost and demands that Kripik not be allowed to hunt and chains him at night. During the night, Kripik mangles his hand while attempting to escape. He flees the post and heads for his family's old village. Hunt and Balk pursue him. Kripik kills his sled dogs for food. In a driving blizzard, Kripik is attacked and injured by a wolf, which he kills. He is rescued by his eldest son Orsodikok.

The Mounties arrive the next morning, and Kripik prevents Orsodikok from killing them. The Mounties say he must leave and never come back. Kripik departs on foot, but Iva goes with him. The Mounties pursue them across the ice, which is breaking up. Sergeant Hunt takes aim at Kripik with his rifle, but cannot shoot because Kripik had saved their lives. Kripik and Iva escape on an ice floe. Hunt tells Balk that the ice will take Kripik and Iva across the inlet, and both will be able to return to Orsodikok next spring.

Cast

Following is a list of the cast members:[2][3]

- Ray Mala as Mala/Kripik

- Lulu Wong Wing as Aba

- Lotus Long as Iva

- Iris Yamaoka as the Second Wife

- Peter Freuchen as Ship Captain

- Edward Hearn as Captain's Mate

- W. S. Van Dyke as Inspector White

- Joseph Sauers as Sergeant Hunt

- Edgar Dearing as Constable Balk

Production

Script and casting

The script for Eskimo was based on books by Danish explorer and author Peter Freuchen.[lower-alpha 2][4] W.S. Van Dyke was assigned by MGM to direct, but it was not a film which Van Dyke was interested in doing. He wrote to his uncle, John Charles Van Dyke, on May 24, 1932, "Am going to film Peter Freuchen's book Eskimo. Don't fancy the job a damn bit, but it brings in the bread and butter."[5]

Van Dyke intended the picture to depict the corrupting influence white culture had on the Eskimos, much as he had done in White Shadows in the South Seas.[6] The script originally ended with Mala and Iva escaping onto the ice, only to drown. But producer Hunt Stromberg felt this ending was too downbeat, and changed it in April 1932 to the ending now seen on film.[7]

Both Stromberg and Van Dyke wanted the Native Alaskans in the film to speak in their native tongue. However, MGM production chief Irving Thalberg worried that intertitles were too distracting and would seem old-fashioned, and Stromberg agreed. By this time, however, it was September 1932. To refilm the shot scenes in English would be prohibitively expensive, and Stromberg changed his mind so that intertitles (not subtitles) were used in the final film to translate the Inupiat language into English.[7]

Stromberg demanded complete authenticity in casting, language, and the depiction of Eskimo life. Casting was critical. Van Dyke cast Inupiat natives (most of them from Barrow, Alaska) for all the minor roles, but Stromberg was so insistent on finding the perfect male lead that casting the title role of Mala/Kripik proved difficult.[8][9] MGM wanted Ray Wise, the actor and cameraman (who later changed his name to Ray Mala),[10] as the star of the picture, and he would become Alaska's first movie star.[11] Wise was a half-Inupiat, half-Russian Jew who previously starred in the 1932 documentary film Igloo. Van Dyke wanted an all-native cast, not a half-native lead, and rejected Wise.[12] A young native Alaskan was hired for the role, but he walked off the set in July 1932 when the stress of filming proved too great. Already on location in Alaska and isolated from the studio, Van Dyke turned to Ray Wise. Not only could Wise perform his own stunts, but Stromberg praised him as an immensely realistic actor.[7] Wise came to Hollywood in 1925, and in addition to his work on Igloo was working as an assistant cameraman. He was hired as a guide for Eskimo's production to Alaska, and was able to offer his services to the film when the original actor quit.[4] Although the film's credits state that professional actors were used only for the Canadian police roles, in fact the major female roles were played by professional actresses Lotus Long and Lulu Wong Ying.[13] Numerous minor roles are also clearly filled by trained actors in make-up and costume.[4]

According to Peter Freuchen, MGM considered filming in Greenland, where Freuchen's novels were set. But the difficult weather and bright summer light (which made filming difficult) dissuaded them, and the production settled on Alaska instead.[14] Freuchen accompanied the production not only as an actor, but as an interpreter as well.[15]

Principal photography and filming locations

The start of production is not clear. A commercial transport ship, the Victoria, took the cast and crew from Seattle, Washington, to Nome, Alaska.[9][15] There, the schooner Nanuk was rented by the studio to take the production team farther north.[13] Originally known as the Pandora, the schooner would next be used in the 1935 production of Mutiny on the Bounty, and rerigged for the 1937 film Maid of Salem.[16] The Nanuk acted as a mobile base of operations, and as a set for the shipboard scenes. MGM bought the schooner outright during the production.[13] On-screen credits for the film claim filming began in April 1932, but The Hollywood Reporter said it began in July[4] and the New York Times said June.[9]

The production had its land-based home at Teller, Alaska.[4] Housing, storage facilities, a film laboratory, and other structures were built to house the cast, crew, and equipment,[15] and the cast nicknamed the site "Camp Hollywood".[17] The crew included 42 cameramen and technicians, six airplane pilots, and Emil Ottinger — a chef from the Roosevelt Hotel.[4] The production took 50 stone (700 lb) (0.32 metric tonnes) of food with them to Alaska, as well as medical supplies, a mobile film processing laboratory, and sound recording equipment.[9] Many native people ate bacon, corn flakes, and oranges for the first time, and became enamored of the food.[14] Film was flown out of Teller back to Los Angeles every seven or eight weeks.[5]

There are varying accounts about how much danger the production encountered during the 1932–33 winter season. The Hollywood Reporter said in October 1932 that the Nanuk was caught in the ice off Alaska and sled dog teams had to be used to rescue the film crew.[4] However, crew on the film noted that the Nanuk wintered in Grantley Harbor at Teller.[13] A press release by MGM in November 1932 claimed that the Nanuk reported via radio that it was frozen in the sea ice and drifting with 35 people aboard, unable to continue shooting until the spring.[18] A report by the New York Times in February 1933 also claimed the Nanuk was locked in sea ice between Teller and Barrow.[19] Peter Freuchen also relates that the Nanuk was blown off course by heavy winds several times.[14]

Filming locations varied widely. Scenes of Eskimo villages on the ice, and some of the polar bear footage (not used), were shot on sea ice 5 miles (8.0 km) off Cape Lisburne, Alaska, in March 1933. For this set, separate camera houses were built some distance away from the igloo sets, and accessed via tunnel below the snow.[13] At one point, a sudden warm spell melted the igloos the production set up to house cast and cameras.[14] Some interior and other shots were filmed on sets at the MGM studios in Culver City, California.[20]

At one point, most of the Native Alaskans in the film went on strike. They were paid $5 per day for being extras, participating in hunts or tribal ceremonies, or for acting in minor roles. Although this was a large sum for Alaska at the time, many decided to strike for $10 or $15 a day. Van Dyke immediately hired strikebreakers from among the other native people as replacements, and the strike ended.[15]

Although cinematographer Clyde DaVinna is credited with the cinematography, additional footage was shot by George Gordon Nogle, Josiah Roberts, and Leonard Smith.[3] Screenwriter John Lee Mahin claims he shot a few of the scenes with Eskimo women when coverage was found to be lacking.[21] Numerous days of shooting were lost in the summer when strong sunlight made it impossible to film.[15] To reduce glare from the snow, most of the sets were sprayed with pink paint from the air.[22]

Because Native Alaskan languages are somewhat staccato in nature and makes heavy of the "kh" sound, sound recordists initially had trouble recording native speech. The "kh" sound overwhelmed the microphones (a problem known as "chopping"), which would then not pick up the following sounds. Significant adjustments were made in order to correct the problem.[23]

Hunting and wolf attack scenes

The scenes of walrus, bowhead whale, and caribou hunting are all real.[13] Because the hunting season for caribou, polar bear, walrus, and whale occur at the same time, the production was forced to spend more than a year in the Arctic (covering two hunting seasons) in order to get the necessary footage.[15]

The walrus and polar bear hunts were filmed in July 1932 at Herald Island in the Chukchi Sea. Walrus carcasses were used as dog food and to attract polar bears. Additional polar bear hunting was filmed in March 1933 off Cape Lisburne. The bowhead whale hunt was filmed from late April to July 1933 in two locations: Off Point Hope, Alaska, and off Cape Serdtse-Kamen on the Chukchi Peninsula.[13] The whale hunting shoot took nearly three months because the whales kept fleeing every time they spotted boats.[15] As depicted in the film, the Inupiat also hunted polar bears by roping and drowning them, but little of this footage made it into the picture.[13]

According to Peter Freuchen, the scene in which the wolf attacks Mala is real. Freuchen says that Mala, armed with a rock and a pistol beneath his fur jacket, spent three afternoons trying to lure a wolf into attacking him. A rifleman and a cinematographer using a camera with a telephoto lens followed at a distance. The wolf attack was filmed from far away, with the rifleman ready to shoot the wolf in case Mala was unable to kill it. As shown in film, Mala was able to kill the wolf without using his pistol or relying on the rifleman, and was not injured in the attack.[24]

Post-production

Principal production appears to have ended about March 25, 1933. Van Dyke was back aboard a commercial ship, headed for California, while Frank Messenger (aboard the Nanuk) continued to shoot second unit footage for the next month or two.[25]

In the summer of 1933, MGM staff realized that additional footage was needed to complete the film. This involved casting an actress for the role. The production staff visited San Francisco, California, to identify an actress for a minor female part.[26] Ray Mala offered the role of Iva to Sadie Brower, a 17-year-old half-Inupiat girl. But after Brower's father refused to let her appear in movies, Lotus Long, an actress of mixed Japanese and Hawaiian ancestry (who could not speak any Eskimo), was cast in the role instead. According to Brower, Long's Eskimo was bad enough as to be unintelligible.[27] Dortuk, Elik, Kemasuk, Nunooruk, and four other Inupiat actors were brought to California to act in the reshoots and new scenes.[23]

William Axt is credited with the musical score.[28] However, some of Modest Mussorgsky's "Night on Bald Mountain" may be heard on the soundtrack when the Eskimos go off to hunt whales. Altogether, pre-production, principal photography, and post-production took 17 months.[24]

The total cost of the picture was reported variously as $935,000[28] or $1.5 million.[4] Even the lower figure was an exceptionally large amount for the time. To recoup its costs, MGM kept the film in circulation for many years.[28] The running time of the film in previews was 160 minutes. Major cuts were made afterward, however. The final running time for the film was either 117 or 120 minutes.[lower-alpha 3][4]

Premieres and critical reception

Premieres

Eskimo premiered at the Astor Theatre in New York City on November 14, 1933.[28] MGM did not promote the film as a tale of colonial corruption or revenge, but rather played up its sexual motifs. The studio placed large neon signs on Broadway Avenue declaring "Eskimo Wife Traders! Weird Tale of the Arctic!" Lobby cards in theaters contained lurid descriptions: "The strangest moral code on the face of the earth — men who share their wives but kill if one is stolen!"[29] MGM more appropriately advertised Eskimo as "the biggest picture ever made".[30]

The film did not do well at the domestic box office, however. As one film scholar put it, "The film's adventurous scenes were certainly impressive, but few Americans would be stirred by Inupiat survival in the far north."[7] To boost receipts, MGM changed the film's title to Eskimo Wife-Traders. But the change did not help, and MGM lost $236,000 on the film domestically.[7] The film was released in the UK and Australia as Mala the Magnificent. The UK premiere was on October 20, 1934, and the Australian premiere on October 31, 1934.[28]

Critical reception

Conrad A. Nervig won the very first Oscar for Best Film Editing for his work on Eskimo.[4] Mordaunt Hall, writing for the New York Times in 1933, generally praised the picture. The script managed to sustain interest in the various scenes, he was surprised to find moments of "genuinely effective comedy", and he found the acting by native people "really extraordinary". He singled out Ray Mala, Lulu Wong Wing, and Lotus Long for being particularly effective in conveying emotion. He also found the use of native language and realistic sounds (recorded in Alaska) one of the film's best elements. However, Hall felt the picture was a bit long, and various hunting scenes (although often thrilling) were too reminiscent of many such scenes in previous motion pictures.[31] Other reviews were also generally positive, but nearly all critics compared the film to other motion pictures (such as Igloo and Nanook of the North) which had also captured exquisite scenery and scenes of Inupiat people.[32] To many critics of the day, the footage of tribal customs and hunting actually made Eskimo a documentary film rather than a drama.[33]

Scholar Peter Geller has more recently criticized the film as depicting the Eskimo as childlike, simple, and mythic "noble savages" rather than as human beings.[34] However, others thought it portrayed them as realistic human beings with feelings. Film historian Thomas P. Doherty concludes that the picture favors scenery and typecasting over real characters.[35]

Eskimo was not the first dramatic film to use an all-native cast for the native roles; that was the 1914 silent film In the Land of the Head Hunters and some would argue Hiawatha (1913 film).[36] Eskimo was, however, the first motion picture filmed in the language of a Native American people,[37] and one of the early features shot in Alaska. Ray Mala became known for his work in Eskimo, and subsequently had a career as a lead and supporting actor in Hollywood, mostly in movie serials and B movies.[30]

Box office

The film grossed a total (domestic and foreign) of $1,312,000: $636,000 in the US and Canada and $676,000 elsewhere resulting in a loss of $236,000.[1]

References

- Notes

- Note that the Mounties don't actually operate in Alaska

- Sources differ as to which books, and how many books, were the basis for the film. Alan Gevinson and the American Film Institute says two books were used, Storfanger and Die flucht ins weisse land.

- Running time varied in some locations because of cuts imposed by local censorship boards.

- Citations

- The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- Cannom 1977, p. 256.

- Reid 2004, p. 69.

- Gevinson 1997, p. 317.

- Van Dyke 1997, p. 149.

- Aleiss 2005, p. 42.

- Aleiss 2005, p. 43.

- Aleiss 2005, pp. 42-43.

- "Pictures and Players". The New York Times. June 5, 1932.

- Gevinson 1997, p. 488.

- Nicholson 2003, p. 104.

- Cannom 1977, p. 248.

- "Filming 'Eskimo' On Location: The Michael Philip Collection, 1932–1933". Archives and Special Collections. UAA-APU Consortium Library. University of Alaska Anchorage. August 1999. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- "Meet Peter Freuchen". The New York Times. November 5, 1933.

- "On Filming 'Eskimo'". The New York Times. November 12, 1933.

- "Sea Lore Kept Alive By Films". Popular Mechanics. June 1937. pp. 877, 116A.

- Cannom 1977, p. 255.

- "Here and There in Hollywood". The New York Times. November 6, 1932.

- "Rene Clair's New Film". The New York Times. February 5, 1933.

- "In the Metro-Goldwyn Studios". The New York Times. June 11, 1933.

- Mahin, McCarthy & McBride 1986, p. 249.

- "Projection Jottings". The New York Times. December 18, 1932.

- "Hollywood Startles Eskimo Actors". The New York Times. August 6, 1933.

- "When Man Meets Wolf". The New York Times. July 16, 1933.

- "Forthcoming Cinema Attractions". The New York Times. March 26, 1933.

- Blackman 1989, p. 90.

- Blackman 1989, pp. 91-92.

- Reid 2004, p. 70.

- Doherty 1999, p. 230.

- Dunham, Mike (March 27, 2011). "Book Recounts Career of the 'Eskimo Clark Gable'". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Hall, Mordaunt (November 15, 1933). "Drama of Frozen North". The New York Times.

- Waldman 1994, pp. 75-76.

- Miller 2012, p. 39.

- Geller 2003, pp. 104-105.

- Doherty 1999, p. 229.

- Hirschfelder & Molin 2012, p. 358.

- Waldman 1994, pp. 75.

Bibliography

- Aleiss, Angela (2005). Making the White Man's Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-98396-X.

- Blackman, Margaret (1989). Sadie Brower Neakok: An Inupiaq Woman. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96813-3.

- Canadian Film Project (1996). Canada and Canadians in Feature Films: A Filmography, 1928–1990. Guelph, Ontario: University of Guelph. ISBN 0-88955-415-3.

- Cannom, Robert C. (1977). Van Dyke and the Mythical City, Hollywood. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-2870-8.

- Doherty, Thomas Patrick (1999). Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930–1934. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11094-4.

- Fetrow, Alan G. (1992). Sound Films, 1927–1939: A United States Filmography. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-546-5.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann (2003). Freeze Frame: Alaska Eskimos in the Movies. Seattle, Wa.: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98337-0.

- Geller, Peter (2003). "Into the Glorious Dawn: From Arctic Home Movie to Missionary Cinema". In Nicholson, Heather Norris (ed.). Screening Culture: Constructing Image and Identity. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0521-4.

- Gevinson, Alan (1997). Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911–1960. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20964-8.

- Hirschfelder, Arlene B.; Molin, Paulette Fairbanks (2012). The Extraordinary Book of Native American Lists. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7709-2.

- Hochman, Stanley (1982). From Quasimodo to Scarlett O'Hara: A National Board of Review Anthology, 1920–1940. New York: Ungar. ISBN 0-8044-2381-4.

- Library of Congress (1936). Catalog of Copyright Entries. Part 1. C. Group 3. Dramatic Composition and Motion Pictures, Vol. 7, for the Years 1934. Washington, D.C.: Copyright Office, Library of Congress.

- Mahin, John Lee; McCarthy, Todd; McBride, Joseph (1986). "John Lee Mahin: Team Player". In McGilligan, Patrick (ed.). Backstory: Interviews With Screenwriters of Hollywood's Golden Age. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05689-2.

- Miller, Cynthia J. (2012). Too Bold for the Box Office: The Mockumentary From Big Screen to Small. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8518-9.

- Morgan, Lael (2011). Eskimo Star: From the Tundra to Tinseltown: the Ray Mala Story. Anchorage, Ak.: Epicenter Press. ISBN 978-1-935347-12-5.

- Nicholson, Heather Norris (2003). Screening Culture: Constructing Image and Identity. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0521-4.

- Reid, John Howard (2004). Award-Winning Films of the 1930s: From 'Wings' to 'Gone With the Wind'. Morrisville, N.C.: Lulu Press. ISBN 978-1-4116-1432-1.

- Van Dyke, John C. (1997). Teague, David W. Teague (ed.). The Secret Life of John C. Van Dyke: Selected Letters. Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-294-2.

- Waldman, Harry (1994). Beyond Hollywood's Grasp: American Filmmakers Abroad, 1914–1945. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-2841-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eskimo (film). |

- Eskimo at IMDb

- Eskimo at AllMovie

- Eskimo at the TCM Movie Database

- Eskimo at the American Film Institute Catalog