London After Midnight (film)

London After Midnight (also marketed as The Hypnotist) is a lost 1927 American silent mystery film with horror overtones directed and co-produced by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney, with Marceline Day, Conrad Nagel, Henry B. Walthall and Polly Moran. The film was distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and was based on the scenario "The Hypnotist", also written by Browning.

| London After Midnight | |

|---|---|

English language theatrical release poster. A direct copy of this poster was also printed in Spanish. | |

| Directed by | Tod Browning |

| Produced by | Tod Browning Irving Thalberg (uncredited) |

| Written by | Waldemar Young (scenario) Joseph W. Farnham (titles) |

| Based on | "The Hypnotist" by Tod Browning |

| Starring | Lon Chaney Marceline Day Conrad Nagel Henry B. Walthall Polly Moran Edna Tichenor Claude King |

| Cinematography | Merritt B. Gerstad |

| Edited by | Harry Reynolds Irving Thalberg (uncredited) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 69 mins[1][2] 47 mins (TCM reconstructed version) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

| Budget | $151,666.14[3] |

| Box office | $1 million[4] |

The last known copy was destroyed in the 1965 MGM vault fire, along with hundreds of other rare early films, making it one of the most sought-after lost films of the silent era.[5] In 2002, Turner Classic Movies aired a reconstructed version,[6] produced by Rick Schmidlin, who used the original script and film stills to recreate the original plot.[7]

Plot

In a cultured and peaceful home on the outskirts of London, the head of the household, Sir Roger Balfour, is found dead from what is initially believed to be a self-inflicted bullet wound.[8] Despite the insistence of Balfour's neighbor, Sir James Hamlin, that his close friend would never have taken his own life, Balfour's death is officially declared a suicide by "Professor" Edward C. Burke, a Scotland Yard inspector and amateur hypnotist.[9][10][11]

Five years later, new tenants move into the Balfour home, but are frightened away by a sinister-looking man with pointed teeth wearing a beaver hat, and a cadaverous-looking woman in a long gown. Their arrival prompts Hamlin to call Scotland Yard. Inspector Burke returns and stays at Hamlin's home, where he discovers that Hamlin and the others there (Balfour's daughter, Lucille; his butler, Williams; and Hamlin's nephew, Arthur Hibbs) had been the only other persons in the Balfour home when he died. Burke remains skeptical that Balfour's death was a murder until the body disappears from the tomb and Balfour is seen walking through the home. This and other eerie events lead Burke to reproduce the crime scene and use hypnosis to induce the culprit into re-enacting the murder, successfully identifying Balfour's killer.[10][11][12][13][3]

Cast

- Lon Chaney as Professor (or Inspector) Edward C. Burke / The Man in the Beaver Hat

- Marceline Day as Lucille Balfour[11]

- Claude King as Roger Balfour / The Stranger[11]

- Polly Moran as Miss Smithson, the New Maid[11]

- Conrad Nagel as Arthur Hibbs[11]

- Edna Tichenor as Luna, a Bat Girl[11]

- Henry B. Walthall as Sir James Hamlin[11]

- Percy Williams as Williams, Balfour's butler[11]

- Andy MacLennan as Bat Girl's Assistant

- Jules Cowles as the Gardener[11]

- Allan Cavan as the Estate Agent[11]

Production notes

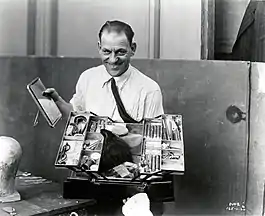

Lon Chaney's makeup for the film included sharpened teeth and the hypnotic eye effect, achieved with special wire fittings which he wore like monocles. Based on surviving accounts, he purposefully gave the "vampire" character an absurd quality, because it was the film's Scotland Yard detective character, also played by Chaney, in a disguise. Surviving stills show this was the only time Chaney used his famous makeup case as an on-screen prop.

The story was an original work by Tod Browning, with Waldemar Young, who had previously worked with Browning on The Unholy Three and The Unknown, as the scenario writer. Young was previously employed as a journalist in San Francisco, during which time he covered several famous murder investigations, a distinction which saw him lauded as knowing "mystery from actual experience."[14]

In the film, Chaney in the role of Burke, adopts different disguises, but the film "even lets the audience into the secrets of his makeup, when, as the detective, he applies a disguise before the eyes of the audience."[15] To add an eerie authenticity to both Chaney's character and the atmosphere within the household used as the location of the movie, the purchasing agent ordered 100 bats to be used within the household as the storyline progresses.[16]

When London After Midnight premiered at the Miller Theater in Missouri, set musicians Sam Feinburg and Jack Feinburg had to prepare melodies to go with the film's supernatural elements. The musicians used Ase's Todd and Eritoken by Greig, Dramatic Andante by Rappe, the Fire Music from Wagner's The Valkyrie along with other unlisted aspects of Savino, Zimonek and Puccini.[17]

Reception

The film grossed $1,004,000 at the box office domestically against a production budget of $151,666.14,[3] and became the most successful collaborative film between Chaney and Browning. However, contemporary accounts by filmgoers and critics suggest it was not one of Chaney and Browning's strongest films. The storyline, called "somewhat incoherent" by The New York Times[3] and "nonsensical" by Harrison's Reports,[18] was a common point of criticism. Nonetheless, the commercial success of London After Midnight saw Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer renew Tod Browning's directorial contract.[19]

A positive review ran in Film Daily, calling it "a story certain to disturb the nervous system of the more sensitive picture patrons. If they don't get the creeps from flashes of grimy bats swooping around, cobweb-bedecked mystery chambers and the grotesque inhabitants of the haunted house, then they've passed the third degree."[18]

The Warren Tribune noted that Lon Chaney is "present in nearly every scene, in a dual role that tests his skill to no small degree." The review highlighted that this subdues Chaney's prominence and allows the plot to be better communicated, but it also causes the film to "not rank among his best productions."[20]

A review by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted: "It is pleasant to report also that there is none of the usual stupid comedy relief in London After Midnight to mar its sinister and creepy scheme. That ought to make it the outstanding mystery film of the year."[11] It however found fault in Tod Browning's direction because the film's atmosphere did not recapture "the intensely weird effect" found in The Cat and the Canary.[11]

Variety wrote that "Young, Browning and Chaney have made a good combination in the past but the story on which this production is based is not of the quality that results in broken house records, adding that, since Burke was "a detached character, mechanical and wooden", he failed to meaningfully connect with the audience.[21]

The New Yorker also wrote that the "directing, acting and settings are all well up to the idea," but "it strives too hard to create effect. Mr. Browning can create pictorial terrors and Lon Chaney can get himself up in a completely repulsive manner, but both their efforts are wasted when the story makes no sense."[22]

Remake

Tod Browning remade the film as a sound film in 1935. This film, called Mark of the Vampire, starred Lionel Barrymore and Bela Lugosi in the roles Lon Chaney had performed in London After Midnight.

Reconstruction

In 2002, Turner Classic Movies commissioned restoration producer Rick Schmidlin to produce a 45-minute reconstruction of the film, using still photographs.[7] The following year, the reconstructed version was released as a part of The Lon Chaney Collection DVD set released by the TCM Archives.[23]

A novelization of the film was written and published in 1928 by Marie Coolidge-Rask.[2]

In 1985, Philip J. Riley published a reconstruction of the film's plot.

In 2016, Thomas Mann published the book, London After Midnight: A New Reconstruction Based on Contemporary Sources, upon the discovery of a previously-unknown 11,000-word Boy's Cinema magazine published in 1928. A second edition was published in 2018 upon the discovery of an alternative French novelization for the film.

Theatrical poster

In 2014, the only contemporary poster known to exist for the film was sold in Dallas, Texas, to an anonymous bidder for $478,000, making it the most valuable movie poster ever sold at public auction. This bidder was later revealed to be Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett.[24] The poster is in his displayed collection at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.[25] (The 1932 film The Mummy held the previous record for a poster's sale at public auction, selling for more than $453,000 in 1997.)[26]

In popular culture

Director Jennifer Kent has stated that images of Lon Chaney's character from London After Midnight inspired the look of the titular character in The Babadook.[27]

In 2010, film director Jonathan Morrill wrote and produced the short subject "Lon Chaney After Midnight". The five and a half minute "mockumentary" premiered at the Egyptian Theatre in 2008, and was uploaded to the internet database of the Library of Congress in 2014. It is viewable there and on Youtube, and recreates a short sequence as "newly discovered footage" found at the Silent Movie Theatre (Fairfax Theatre), in West Hollywood, California.

In 2012, episodes 5 and 6 of Whitechapel featured a killer obsessed with London After Midnight who owned a surviving copy.

References

- Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). "Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era". Midnight Marquee Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

- Giles, Jane (November 8, 2013). "London after Midnight The literary history of Hollywood's first vampire movie". Electric Sheep Magazine. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- Mirsalis, Jon (2008). "London after Midnight (1927)". lonchaney.org. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- Blake, Michael F. (January 1, 1997). A Thousand Faces: Lon Chaney's Unique Artistry in Motion Pictures. Vestal Press. ISBN 9781461730767 – via Google Books.

- The Vampire in Folklore, History, Literature, Film and Television: A Comprehensive Bibliography ISBN 978-0-786-49936-6 p. 148

- "Photo Finish for 'London After Midnight'". The Los Angeles Times. October 27, 2002. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- Vogel, Michelle (2010). Olive Borden: The Life and Films of Hollywood's "Joy Girl". McFarland. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-786-44795-4.

- "London After Midnight". The Brisbane Courier. April 30, 1928. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ""London After Midnight" Opens at Library Today". The Warren Tribune (Warren, Pennsylvania). January 30, 1928. p. 3. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Now Showing". Corsicana Daily Sun (Corsicana, Texas). December 12, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "At the Capitol". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York). December 12, 1927. p. 30. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "London After Midnight, 1927". silenthollywood.com.

- "London After Midnight - Circle". The Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana). January 9, 1928. p. 7. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Lon Chaney Star in London After Midnight Palace". Corsicana Daily Sun (Corsicana, Texas). December 12, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Lon Chaney in Mystery Film at Loew's Colonial". Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania). January 5, 1928. p. 8. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Odd things are Required Among Properties Needed in Making Feature Films". The Evening Independent. May 13, 1932. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- "Lon Chaney Comes to Miller on Wednesday". The Daily Capital News (Jefferson City, Missouri). January 1, 1928. p. 3. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- Soister, John; Nicolella, Henry (2012). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913-1929. McFarland & Company. pp. 335–336.

- "London After Midnight". Northern Star. October 11, 1928. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- "After Six in Warren". The Warren Tribune (Warren, Pennsylvania). January 31, 1928. p. 3. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- "Film Reviews". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc.: 18 December 14, 1927.

- Claxton, Oliver (December 17, 1927). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Company: 103.

- Cline, John; Weiner. Robert G., eds. (2010). From the Arthouse to the Grindhouse: Highbrow and Lowbrow Transgression in Cinema's First Century. Scarecrow Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-810-87655-2.

- "Metallica Guitarist Kirk Hammett's Private Collection of Sci-fi and Horror Movie Posters". The Toronto Sun. July 24, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- https://www.rom.on.ca/en/exhibitions-galleries/exhibitions/its-alive-classic-horror-and-sci-fi-art-from-the-kirk-hammett-0

- "Poster for 'London After Midnight' Sells for $478K". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- "Interview with the Babadook's Writer Director Jennifer Kent". Mountain XPress (Asheville, NC). December 9, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

Further reading

- Everson, William K. (1974). Classics of the Horror Film. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-80650-437-7

- Jacobs, Louis B. "Plastic Dentistry: New Hollywood Art," Photoplay, October 1928. Features London After Midnight.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011). The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-281-4

- Riley, Philip J. (2011). London After Midnight - a Reconstruction. Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-593-93482-8

- Soister, John; Nicolella, Henry (2012). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929. British Library. ISBN 978-0-78643-581-4

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: London After Midnight (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London After Midnight. |

- London After Midnight at IMDb

- Synopsis at AllMovie

- London After Midnight at the TCM Movie Database

- Spanish-language poster for London After Midnight

- Synopsis of London After Midnight at lonchaney.org

- Rumor Spreading That Long-Lost London After Midnight Has Been Found at Bloody Disgusting