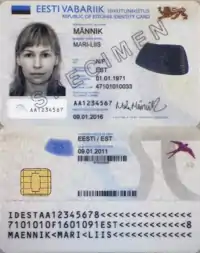

Estonian identity card

The Estonian identity card (Estonian: ID-kaart) is a mandatory identity document for citizens of Estonia. In addition to regular identification of a person, an ID-card can also be used for establishing one's identity in electronic environment and for giving one's digital signature. Within Europe (except Belarus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine)[1] as well as French overseas territories and Georgia, the Estonian ID Card can be used by the citizens of Estonia as a travel document.

The mandatory identity document of a citizen of the European Union is also an identity card, also known as an ID card. The Estonian ID Card can be used to cross the Estonian border, however Estonian authorities cannot guarantee that other EU member states will accept the card as a travel document.[2]

In addition to regular identification of a person, an ID-card can also be used for establishing one's identity in electronic environment and for giving one's digital signature. With the Estonian ID-card the citizen will receive a personal @eesti.ee e-mail address, which is used by the state to send important information. In order to use the @eesti.ee e-mail address, the citizen has to forward it to his or her personal e-mail address, using the State Portal eesti.ee.

The Police and Border Guard Board (PPA) on 25 September 2018 introduced the newest version of Estonia's ID card, featuring additional security elements and a contactless interface, which will begin to be rolled out no later than next year. The new cards also utilize Estonia's own font and elements of its brand. One new detail is the inclusion of a QR code, which will make it easier to check the validity of the ID card. The new design also features a color photo of its bearer, which doubles as a security element and is made up of lines; looking at the card at an angle, another photo appears. The new chip has a higher capacity, allowing the addition of new applications to it.[3]

Scope

The Estonian ID cards are used in health care, electronic banking, signing contracts, public transit, encrypting email and voting. Estonia offers over 600 e-services to citizens and 2400 to businesses.[4] The card's chip stores digitized data about the authorized user, most importantly: the user's full name, gender, national identification number, and cryptographic keys and public key certificates.

Categories of Estonian identity cards

| type | front | back |

|---|---|---|

| Estonian citizen | ||

| EU/EEA citizen | ||

| EU/EEA family permit holder | ||

| long-term residence permit holder | ||

| temporary residence permit holder | ||

| e-Residency of Estonia |

Cryptographic use

The card's chip stores a key pair, allowing users to cryptographically sign digital documents based on principles of public key cryptography using DigiDoc. Since 2016 the DigiDoc software can create files that follow the EU-wide ETSI standard called ASiC-e.[5][6] While it is possible also to encrypt documents using the card-holder's public key, this is used only infrequently, as such documents would become unreadable if the card were lost or destroyed.

By 27 May 2014, 160,809,440 electronic signatures were given, thus averaging to 10 signatures per card user per year.[7]

Under Estonian law, since 15 December 2000 the cryptographic signature is legally equivalent to a manual signature.[8] This law has been superseded by the EU-wide eSignature Directive since 2016.[9]

Uses for identification

The card's compatibility with standard X.509 and TLS infrastructure by providing a client certificate to each person has made it a convenient means of identification for use of web-based government services in Estonia (see e-Government). All major banks, many financial and other web services support ID-card based authentication. Adding support of Estonian ID-card based identification is very simple nowadays because majority of used browsers, web servers and other software supports TLS (SSL) client-certificate based authentication and Estonian ID-card use exactly that system.

Web discussion forums

Web commentary columns of some Estonian newspapers, most notably Eesti Päevaleht, used to support ID-card based authentication for comments. This approach caused some controversy in the internet community.[10]

Public transport

Larger cities in Estonia, such as Tallinn and Tartu, have arrangements making it possible for residents to purchase "virtual" transportation tickets linked to their ID cards.

Period tickets can be bought online via electronic bank transfer, by SMS, or at public kiosks. This process usually takes less than a few minutes and the ticket is instantly active from the moment of purchase or since the first use of the ticket.[11]

Customers also have the option of requesting e-mail or SMS notification alerting them when the ticket is about to expire, or of setting up automatic renewal through internet banking services.

To use the virtual ticket, customers must carry their ID card with them whenever they use public transport. During a routine ticket check, users are asked to present their ID card, which is then inserted into a special device. This device then confirms that the user holds a valid ticket, and also warns if the ticket is about to expire. The ticket check usually takes less than a second.

Ticket information is stored in a central database, not on the ID card itself. Thus, to order a ticket, it is not necessary to have an ID-card reader. Ticket controllers have access to a local archive of the master database. If the ticket was purchased after the local archive was updated, the ticket device is able to confirm the ticket from the master database over mobile data link.

Electronic voting

The Estonian ID card is also used for authentication in Estonia's Internet-based voting program called i-Voting.

In February 2007, Estonia was the first country in the world to institute electronic voting for parliamentary elections. Over 30,000 voters participated in the country's e-election.[12] In the Parliamentary election of 2011 140,846 votes were cast electronically representing 24% of total votes.[13]

The software used in this process is available for Microsoft Windows, macOS and Linux.

Use as a travel document

Since Estonia's accession to the European Union (EU) in 2004, Estonian citizens who possess an Estonian identity card have been able to use it as an international travel document, in lieu of a passport, for travel within European Economic Area (except Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine) as well as French overseas departments and territories, Andorra, San Marino, Monaco, Vatican State, Northern Cyprus and Georgia.

However, non-Estonian citizens resident in Estonia are unable to use their Estonian identity cards as an international travel document.

Security issues

Weak key vulnerability

In August 2017, a security threat was discovered that affected 750,000 ID and e-residency cards issued between 16 October 2014 and 26 October 2017.[14]

The relevant Estonian organisations responsible for the ID card has since released a patch in the form of a certificate update, and published a detailed walkthrough on https://www.id.ee to check if an update is required, and how to perform it.[15] The update can also be performed in the service offices of the Estonian Police and Border Guard Board. Online updating can be performed until 31 March 2018 (incl.), after which the certificates of affected cards will be invalidated. Thereafter, a new e-residency or ID-card must be applied for in order to use it electronically.[16]

On 2 November 2017, the Estonian government announced, that online updating of vulnerable ID-cards would be suspended to all users for between 3–5 November 2017 in favour of the country's officials and the 35,000 doctors, who use their cards most actively.[17]

This temporary suspension of updates to all users has since been lifted, so that owners of ID cards and e-residency cards can now update their certificates.

In October 2017, it was reported that a code library developed by Infineon, which had been in widespread use in security products such as smartcards and TPMs, had a flaw (later dubbed the ROCA vulnerability) that allowed private keys to be inferred from public keys.[18][19] As a result, all systems depending upon the privacy of such keys were vulnerable to compromise, such as identity theft or spoofing.[18] Affected systems include 750,000 Estonian national ID cards,[18] and Estonian e-residency cards.

On 2 November 2017 the Estonian prime minister Jüri Ratas announced, that due to 'imminent risk' of attack, the authorities are to temporarily disable the certificates of affected ID cards at 00:00, 4 November 2017. According to government officials, the existing infrastructure is incapable of updating the certificates of this large amount of affected cards before the deadline. Priority updates are to be supplied between 3–5 November to government employees and 35,000 medical staff.[20]

See also

- National identity cards in the European Union

- Estonian passport

- Estonian seafarer's discharge book

- Estonian temporary travel document

- Estonian alien's passport

- Estonian travel document for refugees

- Estonian nationality law

- Visa requirements for Estonian citizens

- Visa requirements for Estonian non-citizens

- e-Residency of Estonia

- e-Estonia

- ROCA vulnerability

References

- "Validity of ID Card". North Cyprus.

- "Estonian ID Card Information by Estonian Police and Border Guard Board". Police and Border Guard Board.

- "New Estonian ID Card 2019". ERR. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- Economist Magazine, Estonia takes the plung https://www.economist.com/news/international/21605923-national-identity-scheme-goes-global-estonia-takes-plunge

- https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/319100_319199/31916201/01.01.01_60/en_31916201v010101p.pdf

- https://www.id.ee/?id=37026

- Estonian ID-card

- Elektrooniline Riigi Teataja: Digitaalallkirja seadus (this version valid from 8 January 2004 up to 31 December 2007)

- https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/CEFDIGITAL/Introduction+to+e-signature

- Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine PRIIT HÕBEMÄGI: Anonüümsete kommentaaride lõpetamise kommentaarid

- https://www.tartu.ee/en/node/1250

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2012-12-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) idBlog - The number of electronic voters tripled

- http://www.vvk.ee/riigikogu-valimised-2011/statistika-2011/e-haaletamise-statistika/

- "Possible security risk affects 750,000 Estonian ID-cards". Estonian World. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- "Check whether your document certificates need to be updated". Renewal of Certificates. PPA. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Pulver, Andres (2017-11-01). "ID-kaardi sertifikaatide uuendaja peab arvestama järjekorraga" [The renewer of ID-card certificates must take queuing into account]. Virumaa Teataja (in Estonian). Postimees. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Olup, Nele-Mai; Pau, Aivar (2017-11-02). "Blogi ja fotod: valitsus otsustas e-riigist välja lõigata enam kui pooled ID-kaardid" [The government decided to cut off more than half of ID-cards from the e-state] (in Estonian). Postimees. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Goodin, Dan (16 October 2017). "Millions of high-security crypto keys crippled by newly discovered flaw". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Parsovs, Arnis (14 August 2020). "Estonian Electronic Identity Card: Security Flaws in Key Management". Proc. 29th USENIX Security Symposium. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Jõevere, Kristjan; Helme, Kristi (2 November 2017). "BLOGI ja FOTOD: Turvariskiga ID-kaartide sertifikaadid peatatakse alates homme õhtust" [The certificates of vulnerable ID-cards will be stopped from tomorrow evening]. Delfi.ee (in Estonian). Ekspress Grupp. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

External links

- New Estonian ID Card 2019

- Information about Estonian ID Card by Estonian Police and Border Guard Board

- Information about Estonian ID Card by Prado Consilium

- Sample ID Card of an Estonian citizen, issued by Estonian Police and Border Guard Board starting from 01.01.2011

- A map of Estonian representations abroad

- Certificate of Return for Estonian citizen

- Identity Documents Act

- Visa-Free Country List by Estonian Foreign Ministry

- Passport Index Visa-Free Score Estonian Passport

- Henley & Partners Visa Restrictions Index Map

- Issuing authority's official website in English

- ID Ticket website

- ID card official information page

- ID card information on the e-estonia website