Ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia

This article describes ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia from 1918 until 1992.

Background

Czechoslovakia was founded as a country in the aftermath of World War I with its borders set out in the Treaty of Trianon and Treaty of Versailles, though the new borders were approximately de facto established about a year prior. One of the main objects of these treaties was to secure independence for minorities previously living within the Kingdom of Hungary or to reunify them with an existent nation-state.

However some territorial claims were based on economic grounds instead of ethnic ones, for instance the Czechoslovak borders with Poland (to include coal fields and a railway connection between Bohemia and Slovakia) and Hungary (on economic and strategic grounds), which resulted in successor states with percentages of minorities almost as high as in Austria-Hungary before.[1] Czechoslovakia had the highest proportion of minorities, who constituted 32.4% of the population.[2]

During World War II, the Jewish and Romani minorities had been exterminated by the Nazis, and after the war most Germans and many Hungarians were expelled under the Beneš decrees. Afterwards, other minority groups migrated to Czechoslovakia, Roma from Hungary and Romania, Bulgarians fleeing the Soviet troops, Greeks and Macedonians fleeing the Greek Civil War. Later, migrant workers and students came from other Communist bloc countries, including Vietnamese and Koreans.

Demographics

| Regions | "Czechoslovaks" (Czechs and Slovaks) |

Germans | Hungarians | Rusyns | Jews | others | Total population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | 4 382 788 | 2 173 239 | 5 476 | 2 007 | 11 251 | 93 757 | 6 668 518 |

| Moravia | 2 048 426 | 547 604 | 534 | 976 | 15 335 | 46 448 | 2 649 323 |

| Silesia[4] | 296 194 | 252 365 | 94 | 338 | 3 681 | 49 530 | 602 202 |

| Slovakia | 2 013 792 | 139 900 | 637 183 | 85 644 | 70 529 | 42 313 | 2 989 361 |

| Carpathian Ruthenia | 19 737 | 10 460 | 102 144 | 372 884 | 80 059 | 6 760 | 592 044 |

| Czechoslovak Republic | 8 760 937 | 3 123 568 | 745 431 | 461 849 | 180 855 | 238 080 | 13 410 750 |

| Ethnic group |

census 1921 1 | census 1930 | census 1950 | census 1961 | census 1970 | census 1980 | census 1991 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Czechs | 6,758,983 | 67.5 | 7,304,588 | 68.3 | 8,343,558 | 93.9 | 9,023,501 | 94.2 | 9,270,617 | 94.4 | 9,733,925 | 94.6 | 8,363,768 | 81.2 |

| Moravians | 1,362,313 | 13.2 | ||||||||||||

| Silesians | 44,446 | 0.4 | ||||||||||||

| Slovaks | 15,732 | 0.2 | 44,451 | 0.4 | 258,025 | 2.9 | 275,997 | 2.9 | 320,998 | 3.3 | 359,370 | 3.5 | 314,877 | 3.1 |

| Poles | 103,521 | 1.0 | 92,689 | 0.9 | 70,816 | 0.8 | 66,540 | 0.7 | 64,074 | 0.7 | 66,123 | 0.6 | 59,383 | 0.6 |

| Germans | 3,061,369 | 30.6 | 3,149,820 | 29.5 | 159,938 | 1.8 | 134,143 | 1.4 | 80,903 | 0.8 | 58,211 | 0.6 | 48,556 | 0.5 |

| Ukrainians | 13,343 | 0.1 | 22,657 | 0.2 | 19,384 | 0.2 | 19,549 | 0.2 | 9,794 | 0.1 | 10,271 | 0.1 | 8,220 | 0.1 |

| Rusyns | 1,926 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||

| Russians | 6,619 | 0.1 | 5,051 | 0.0 | 5,062 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Vietnamese | 421 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||

| Hungarians | 7,049 | 0.1 | 11,427 | 0.1 | 13,201 | 0.1 | 15,152 | 0.2 | 18,472 | 0.2 | 19,676 | 0.2 | 19,932 | 0.2 |

| Romani[5] | 227 | 0.0 | 19,770 | 0.2 | 19,392 | 0.2 | 32,903 | 0.3 | ||||||

| Jews | 35,699 | 0.4 | 37,093 | 0.4 | 218 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Yugoslavs | 4,749 | 0.0 | 3,957 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Romanians | 966 | 0.0 | 3,205 | 0.0 | 1,034 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Others/undeclared | 10,038 | 0.1 | 5,719 | 0.1 | 11,441 | 0.1 | 10,095 | 0.1 | 36,220 | 0.4 | 39,300 | 0.4 | 39,129 | 0.4 |

| Total | 10,005,734 | 10,674,386 | 8,896,133 | 9,571,531 | 9,807,697 | 10,291,927 | 10,302,215 | |||||||

| 1 On the territory of the census date. | ||||||||||||||

| Ethnic group |

census 1950 | census 1961 | census 1970 | census 1980 | census 1991 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Slovaks | 86.6 | 85.3 | 85.5 | 4,317,008 | 86.5 | 4,519,328 | 85.7 | |||

| Hungarians | 10.3 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 559,490 | 11.2 | 567,296 | 10.8 | |||

| Romani1 | – | – | – | – | – | 75,802 | 1.4 | |||

| Czechs | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 57,197 | 1.1 | 59,326 | 1.1 | |||

| Ruthenians | 1.4 | – | 0.9 | 0.7 | 17,197 | 0.3 | ||||

| Ukrainians | 13,281 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| Others/undeclared | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 22,105 | 0.4 | ||||

| Total | 3,442,317 | 4,174,046 | 4,537,290 | 4,991,168 | 5,274,335 | |||||

| 1 Before 1991 the Romani were not recognized as a separate ethnic group | ||||||||||

Linguistic rights in the First Republic

According to article 128 §3 of the 1920 Constitution "Citizens of the Czechoslovak Republic may, within the limits of the common law, freely use any language they chose in private and business intercourse, in all matters pertaining to religion, in the press and in all publications whatsoever, or in public assemblies."[8]

These rights were also provided for in article 57 of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1919: "The Czecho-Slovak State accepts and agrees to embody in a Treaty with the Principal Allied and Associated Powers such provision as may be deemed necessary by these Powers to protect the interests of inhabitants of that State who differ from the majority of the population in race, language or religion."[9]

"In addition, the Language act granted minorities the right to address courts, offices and state organs in their own language, but only in communities where that national minority comprised more than 20 percent of the population."[10]

The proceedings in the parliament were held either in the official languages of Czechoslovakia, Czech and Slovak, or in one of the recognized minority languages. Practically, everyone spoke their own language.[11]

Recognized minorities in the Socialist Republic

A Government Council for Nationalities was established in 1968 in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in accordance to Article 5 of the Constitutional Law No. 144/1968.[12]

Conflicts Between Czechs and Slovaks

After World War I, the Czechs outnumbered Slovaks two to one in the new Czechoslovak state.[13] The Slovaks lived in the shadow of the more internationally recognized Czech leadership and the great capital of Prague.[13] The relationship between the Czechs and Slovaks was asymmetrical: Slovakia was considered an agrarian appendage to the highly industrial Czech nation,[13][14] and the Czechs viewed Slovak culture as lacking in maturity and refinement.[14] The languages of the two nations are closely related and mutually intelligible, and many Czechs viewed Slovak as a caricature of Czech.[14] In his 1934 memoirs, the President of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, writes he said in a 1924 interview to a French journalist of Le Petit Parisien: «There is no Slovak nation, it has been invented by Hungarian propaganda. The Czechs and Slovaks are brothers. They understand each other perfectly. All that separates them is the cultural level – the Czechs are more developed than the Slovaks, because the Magyars kept them in the dark. (...) In one generation there will be no difference between the two branches of our national family.»[15] However the interview is nowhere to be found in the scanned full archives of Le Petit Parisien.[16]

Germans in Czechoslovakia

There were two German minority groups in the interwar Czechoslovakian Republic, the Sudeten Germans in Bohemia and Moravia (present-day Czech Republic) and the Carpathian Germans in Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia (present-day Ukraine).

In addition, there was a sizeable German-speaking urban Jewish minority, and several Jewish politicians were elected as members of German minority parties like the German Social Democratic Workers Party in the Czechoslovak Republic or the German Democratic Liberal Party.

Poles in Czechoslovakia

The Polish minority in Czechoslovakia (Polish: Polska mniejszość w Czechosłowacji, Czech: Polská národnostní menšina v Československu, Slovak: Poľská menšina v Československu) (today the Polish minority in the Czech Republic (Polish: Polska mniejszość narodowa w Republice Czeskiej, Czech: Polská národnostní menšina v České republice) and Slovakia (Polish: Polska mniejszość na Słowacji, Slovak: Poľská menšina na Slovensku) is the Polish national minority living mainly in the Zaolzie region of western Cieszyn Silesia. The Polish community is the only national (or ethnic) minority in the Czech Republic that is linked to a native specific geographical area.[17] Zaolzie is located in the north-eastern part of the country. It comprises Karviná District and the eastern part of Frýdek-Místek District. Many Poles living in other regions of the Czech Republic have roots in Zaolzie as well.

Poles formed the largest ethnic group in Cieszyn Silesia in the 19th century, but at the beginning of the 20th century the Czech population grew. The Czechs and Poles collaborated on resisting Germanization movements, but this collaboration ceased after World War I. In 1920 the region of Zaolzie was incorporated into Czechoslovakia after the Polish–Czechoslovak War. Since then the Polish population demographically decreased. In 1938 it was annexed by Poland in the context of the Munich Agreement and in 1939 by Nazi Germany. The region was then given back to Czechoslovakia after World War II. Polish organizations were re-created, but were banned by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. After the Velvet Revolution, Polish organizations were re-created again and Zaolzie had adopted bilingual signs.

Hungarians in Czechoslovakia

Hungarians (and other minorities e.g. Germans and Rusyns) were excluded from the constituent assembly, barring them from having any influence on the new Czechoslovak constitution.[18] Later on, all the minorities gained the right to use their languages in municipalities where they constituted at least 20% of the population even in communication with government offices and courts. However due to gerrymandering and disproportionate distribution of population between Bohemia and Slovakia the Hungarians had little (if any) representation in the National Assembly and thus their influence on the politics of Czechoslovakia remained limited. The same considerations had limited the Slovak intelligentsia's political power as well.[18]

Jews in Czechoslovakia

During communism there were no signs of organized Jewish life and the situation was similar to others communities of Central and Eastern Europe controlled directly by the state.[19] Most of the Jews left the country for Israel or the United States who wanted to follow Jewish lives and freedom.[19] For many years there has been no religious leadership.[19]

Roma in Czechoslovakia

After World War I, the Roma people formed an ethnic community, living on the social periphery of the mainstream population.[20] The state always focused on the Roma population not as a distinct ethnic minority, but rather perceived it as a particularly anti-social and criminal group.[20] This attitude was reflected in the policy of collecting special police evidence—fingerprint collections of members of Romany groups (1925), a law about wandering Roma (1927).[20]

Racism was not an unknown phenomenon under communism.[21] Roma people were forced to resettle in small groups around the country left them isolated.[21] This policy of the state was oriented toward one of assimilation of the Roma people (in 1958, Law No. 74, "On the permanent settlement of nomadic and semi-nomadic people"), forcibly limited the movement of that part of the Roma (perhaps 5%–10%) who still traveled on a regular basis.[20] In the same year, the highest organ of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia passed a resolution, the aim of which was to be "the final assimilation of the Gypsy population". The "Gypsy question" was decreased to a "problem of a socially-backward section of the population".[20] During this period, the governments actively supported sterilisation and abortion for Roma women and the policy was not repealed until 1991.[21]

The popular perception of Romani even before 1989 was of lazy, dirty criminals who abused social services and posed a significant threat to majority values.[21]

Rusyns (Ruthenians/Ukrainians) in Czechoslovakia

After World War II, the Rusyn nationality was declared to be Ukrainian in Czechoslovakia.[22] The Rusyns refused Ukrainian identity, instead declaring their nationality as Slovak.[22] Rusyn cultural institutions were changed to Ukrainian, and the usage of the Rusyn language in official communications ceased.[22] Most settlement had only a Slovak-language school and a Slovak identity and orientation were adopted by most of the Rusyn populace, and they were, in effect, de-nationalized.[22]

Smaller ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia

See also

References

- Hugh LeCaine Agnew,The Czechs and the lands of the Bohemian crown , Hoover Press, 2004, p. 177 ISBN 978-0-817-94492-6.

- Dr. László Gulyás (2005). Két régió – Felvidék és Vajdaság – sorsa Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchiától napjainkig (The fate of two regions – Upper Hungary and Vojvodina – from Austria-Hungary to today) (in Hungarian). Hazai Térségfejlesztő Rt. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Slovenský náučný slovník, I. zväzok, Bratislava-Český Těšín, 1932

- The 1921 and 1930 census numbers are not accurate since nationality depended on self-declaration and many Poles declared Czech nationality mainly as a result of fear of the new authorities and as compensation for some benefits. cf. Zahradnik, Stanisław; Marek Ryczkowski (1992). Korzenie Zaolzia. Warszawa – Praga – Trzyniec: PAI-press. OCLC 177389723.

- In census people can leave the "nationality" field empty and they can also write down any nationality or ethnicity they want. Most of Romani people fill in the Czech nationality. Thus, the real number of Romani in the country is estimated to be around 220,000. Petr Lhotka: Romové v České republice po roce 1989 Archived 20 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Population by nationality (per cent) from the housing and population censuses in 1950 – 2001, INFOSTAT, Bratislava and Faculty of Natural Sciences of Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia 2009

- Table 11. Resident population by nationality – 2001, 1991 Archived 15 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Population and Housing Census. Resident population by nationality.

- The constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic (1920), Internet Archive, Cornell University Library

- Text of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919), from the website of the Australasian Legal Information Institute, hosted by UNSW and UTS

- Bakke, Elisabeth (2002). "The principle of national self-determination in Czechoslovak constitutions 1920–1992" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- see e.g. the Opening of the 1935 session of the Czechoslovak Chamber of Deputies with every member taking the oath in his own language Archived 14 September 2012 at Archive.today, Digitalized Archives of the Czechoslovak Parliament Archived 7 September 2012 at Archive.today

- Government Council for National Minorities

- Charles Krupnick, Almost NATO: partners and players in Central and Eastern European security, Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, p. 48

- "Culture of Czech Republic". www.everyculture.com.

- Tomáš G. Masaryk, Cesta demokracie II (The path of democracy), Prague, 134, p.78-79, full quotation translated in: Elisabeth Bakke, «The Making of Czechoslovakism in the First Czechoslovak Republic», p.35 n22, in: Martin Schulze Wessel (ed.), Loyalitäten in der Tschechoslowakischen Republik 1918–1938. Politische, nationale und kulturelle Zugehörigkeiten, Munich, R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2004

- the scanned full archives of Le Petit Parisien

- European Commission 2006.

- Béla Angyal (2002). Érdekvédelem és önszerveződés – Fejezetek a csehszlovákiai magyar pártpolitika történetéből 1918–1938 (Protection of interests and self-organization – Chapters from the history of the politics of Hungarians in Czechoslovakia) (PDF) (in Hungarian). Lilium Aurum. pp. 23–27. ISBN 80-8062-117-9. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Hegedus, Martin. "Jews in Slovakia". Slovakia.org. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Orgovanova, Klara. "Roma in Slovakia". Slovakia.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- George Lawson, Economic and Social Research Council (Great Britain), Negotiated revolutions: the Czech Republic, South Africa and Chile, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, p. 115 ISBN 978-0-754-64327-2

- Custer, Richard D. "What is a Rusyn?". Slovakia.org. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

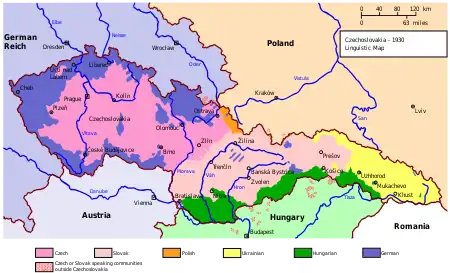

Maps

Maps showing the ethnic, linguistic or religious diversity are to be considered with much precaution as they may reflect the national or ideological beliefs of their author(s), or simply include errors. The same can be said about ethnic, linguistic or religious censuses, as the governments that organize them are not necessarily neutral.

- Races in Austria-Hungary, The Historical Atlas, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1911

- Tchécoslovaquie. Ethnographie in: Louis Eisenmann, La Tchéco-Slovaquie, F. Paillar, 1921, p. 31

- Map of the Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1945). Map of nationalities, Atlas světa, Vojenský zeměpisný ústav v Praze (Military geographical institute in Prague), 1931