Germans

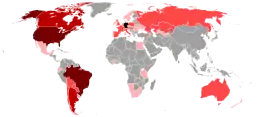

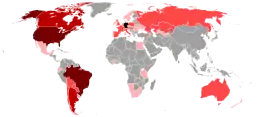

The Germans (German: Deutsche) are a Germanic[7] ethnic group native to Central Europe.[8][9][10] Speaking the German language is the most important characteristic of modern Germans,[10][11][12] but they are also characterized by a common German culture, descent and history.[11] The term "German" may also be applied to any citizen,[13] native or inhabitant of Germany,[14][15] or member of the Germanic peoples,[15][16][17][18][19] regardless of whether they are of German ethnicity or not. Estimates on the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 to 150 million, and most of them live in Germany.[9]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 100–150 million[1]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 75,000,000[2][3] | |

| c. 7,600,000 (disputed)[4] | |

| c. 5,000,000[5] | |

| c. 4,200,000 (disputed)[4] | |

| c. 3,000,000[5] | |

| c. 1,200,000[4] | |

| c. 900,000[4] | |

| c. 840,000[4] | |

| c. 700,000[4] | |

| c. 500,000[5] | |

| c. 450,000[5] | |

| c. 280,000[4] | |

| c. 250,000[4] | |

| c. 170,000[5] | |

| c. 110,000[5] | |

| c. 100,000[5] | |

| c. 75,000[5] | |

| Languages | |

| German | |

| Religion | |

| 1/3rd Roman Catholic[6] 1/3rd Protestant[6] 1/3rd Irreligion[6] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Germanic peoples | |

The German ethnicity developed among early Germanic peoples of Central Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The Kingdom of Germany emerged from the eastern remains of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century, and formed the core of the Holy Roman Empire. In subsequent centuries the German population grew considerably and a substantial number of Germans migrated to Eastern and Northern Europe. Following the Reformation in the 16th century, the German lands became divided into Roman Catholic and Protestant states. The 19th century saw the dismemberment of the Holy Roman Empire and the growth of German nationalism, with the state of Prussia incorporating the majority of the Germans into the German Empire, while a substantial number of Germans also inhabited Austria-Hungary. During this time a large number of Germans emigrated to the New World, particularly to the United States, Canada and Brazil. The Russian Empire also contained a substantial German population.

In the aftermath of World War I, Austria-Hungary and the German Empire were partitioned, resulting in many Germans becoming ethnic minorities in newly established countries. In the chaotic years that followed, Adolf Hitler became the dictator of Nazi Germany and embarked on an genocidal campaign to unify all Germans under his leadership. This campaign resulted in World War II and the Holocaust. In the aftermath of Germany's defeat in the war, the country was occupied and partitioned, while millions of Germans were expelled from Eastern Europe. In 1990, the states of West and East Germany were reunified. In modern times, remembrance of the Holocaust has become an integral part of German identity (Erinnerungskultur).

Owing to their long history of political fragmentation, the Germans are culturally diverse and often have strong regional identities. The arts and sciences are an integral part of German culture, and the Germans have produced a large number of prominent personalities in a number of disciplines.

Names

The German endonym Deutsche is derived from the High German term diutisc, which means "ethnic" or "relating to the people". This name was used for Germanic peoples in Central Europe since the 8th century, during which a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge among them.[2]

The English term Germans is derived from the ethnonym Germani, which was used for Germanic peoples in ancient times.[2][20] Since the early modern period, it has been the most common name for the Germans in English. The term "Germans" may also be applied to any citizen, native or inhabitant of Germany, a person of German descent,[14][15] or member of the Germanic peoples,[15][16][17][18][19] regardless of whether they are of German ethnicity or not.

History

.PNG.webp)

Ancient history

The German ethnicity emerged among early Germanic peoples of Central Europe, particularly the Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringii, Alemanni and Baiuvarii.[21] Germanic culture originated in parts of what is now Northern Germany, and has been associated with the Nordic Bronze Age and the Jastorf culture, which flourished in Northern Germany and Scandinavia during the Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[21] The Germanic peoples have inhabited Central Europe since at least the Iron Age.[2]

From their northern homeland, the Germanic peoples expanded southwards in a series of great migrations.[22] Much of Central Europe was at that time inhabited by Celts, who are associated with the La Tène culture.[21] Since at least the 2nd century BC the Germanic peoples began displacing Celts.[23] It is likely that many of these Celts were Germanized by migrating Germanic peoples.[21]

Detailed information about the Germanic peoples is provided by the Roman general Julius Caesar, who campaigned in Germania in the 1st century BC. By this time Germanic peoples are believed to have dominated an area stretching from the Rhine in the west to the Vistula in the east, and the Danube in the south to Scandinavia in the north. Under Caesar's successor Augustus, the Romans sought to conquer the Germanic peoples and colonize Germania, but these efforts were significantly hampered by the victory of Arminius at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, which is considered a defining moment in German history.[21] The early Germanic peoples are famously described in Germania by the 1st century Roman historian Tacitus. At this time, the Germanic peoples were fragmented into a large number of tribes who were frequently in conflict with both the Roman Empire and one another.[24] By the 3rd century, Germanic peoples were beginning to merge into great coalitions, and had begun conquering and settling areas within the Roman Empire. During the 4th and 5th centuries, in what is known as the Migration Period, Germanic peoples overran the decaying Roman Empire and established new kingdoms within it. Meanwhile, formerly Germanic areas in parts of Eastern Europe were settled by Slavs.[23]

Medieval history

The beginnings of the German states can be traced back to the Frankish king Clovis I, who established the kingdom of Francia in the 5th century. In subsequent centuries the power of the Franks grew considerably.[23] By the 8th century AD, the Germanic populations of Central Europe were known as diutisc, an Old High German term meaning "ethnic" or "relating to the people". The endonym of the Germans is derived from this word. From this time on, a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge.[2]

By the early 9th century AD, large parts of Central Europe had been united under the rule of the Frankish leader Charlemagne, who defeated the Lombards, Saxons and other Germanic peoples and established the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne was crowned emperor by Pope Leo I in 800.[23] During the rule of Charlemagne's successors, the Carolingian Empire descended into civil war. The empire was eventually partioned at the Treaty of Verdun (843), resulting in the creation of the states of West Francia, Middle Francia and East Francia (led by Louis the German). Beginning with Henry the Fowler, Saxon dynasties dominated the German lands, and under his son Otto I, Middle Francia and East Francia, which were mostly German, became part of the Kingdom of Germany, which constituted the core of the Holy Roman Empire.[25] Leaders of tribal duchies such as Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia, Saxony and Lorraine continued to wield considerable power independent of the king.[23] German kings were elected by members of the noble families, who often sought have weak kings elected in order to preserve their own independence. This prevented an early unification of the Germans and contributed to the formation of strong German national groups, such as the Bavarians, Swabians and Franconians.[26][27]

A warrior nobility dominated the feudal German society of the Middle Ages, while the majority of the German population consisted of peasants with little political rights.[23] The church played an important role among Germans in the Middle Ages, and competed with the nobility for power.[28] Between the 11th and 13th centuries, Germans actively participated in five Crusades to "liberate" the Holy Land.[28]

During the Middle Ages, German political power was imposed on Slavic populations in the east. This process was accompanied by the migration of Germans into conquered territories, in what is known as the Ostsiedlung. Over time, some Slavic populations were assimilated by Germans, resulting in many Germans acquiring substantial Slavic ancestry.[25] From the 11th century, the German lands came under the domination of the Swabian Hohenstaufen family. The German population expanded significantly during this time.[27] Trade increased and there was a specialization of the arts and crafts.[28] From the 12th century, many Germans settled as merchants and craftsmen in the Kingdom of Poland, were they came to constitute a significant proportion of the population in many urban centers such as Gdańsk.[25]

The late 13th century saw the election of Rudolf I of the House of Habsburg to the German throne, and the Habsburg family would continue to play an important role in German history for centuries afterwards. They competed for power in the German lands with several noble families, most notably the Limburg-Luxemburg dynasty and the House of Wittelsbach. During the 13th century, the Teutonic Knights began conquering the Old Prussians, and established what would eventually become the powerful German state of Prussia.[27]

The German territories continued to grow in the late Middle Ages. Great urban centers increased in size and wealth and formed powerful leagues, such as the Hanseatic League and the Swabian League, in order to protect their interests, often through supporting the German kings in their struggles with the nobility.[27] These urban leagues significantly contributed to the development of German commerce and banking. German merchants of Hanseatic cities settled in cities throughout Northern Europe beyond the German lands.[29]

Modern history

The introduction of printing by the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg contributed to the formation of a new understanding of faith and reason. At this time, the German monk Martin Luther ushered the Reformation, which was to have a major impact on German history.[28] In response to the advance of Protestantism, Catholics began the Counter-Reformation.[30] The resulting religious schism among he Germans was a leading cause of the Thirty Years' War, which led to the death of millions of Germans. The war ended with the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which resulted in the central authority of the Holy Roman Empire being significantly reduced.[31] Among the most powerful German state to emerge in the aftermath of the Peace of Westphalia was Prussia, which was under the rule of the House of Hohenzollern.[30] In the 18th century, German culture was much influenced by the Enlightenment.[31]

.png.webp)

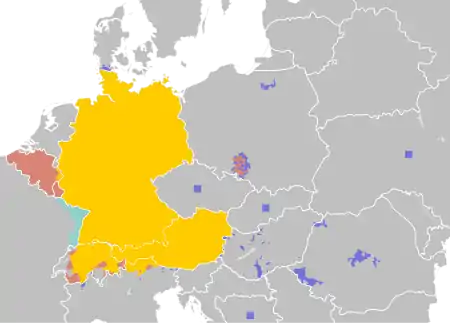

After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of German unity began to emerge in the 18th century.[2] The Holy Roman Empire continued to exist until being dissolved by Napoleon in 1806. The Napoleonic conquest of Central Europe ushered great social, political and economic changes, and catalyzed a national awakening among the Germans. Already in the late 18th century, German intellectuals such as Johann Gottfried Herder articulated the concept of a German identity rooted in language, and this notion helped spark the German nationalist movement, which sought to unify the Germans into a single nation state.[26] Eventually, shared descent and culture came to be a defining characteristic of the Germans.[24] The Napoleonic Wars ended with the Congress of Vienna (1815), during which the German states were loosely united in the German Confederation. The confederation came to be dominated by the Catholic Austrian Empire, to the dismay of many German nationalists, who saw the German Confederation as an inadequate answer to the German Question.[30]

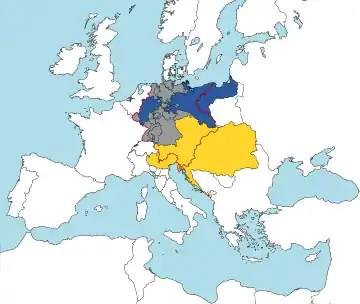

Throughout the 19th century, the German state of Prussia continued to grow in power.[32] German revolutionaries of the revolutions of 1848 were able to create a temporary Frankfurt Parliament, but failed in their aims to immediately unify the German homeland. The Prussians proposed an Erfurt Union of the German states, but this effort was torpedoed by the Austrians through the Punctation of Olmütz (1850), resulting in the recreation of the German Confederation. As a response, the Prussians sought to use the Zollverein customs union to increase its power among the German states.[30] Under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, Prussia and allied German states defeated Denmark in the Second Schleswig War and the Austrian Empire in the Austro-Prussian War, subsequently establishing the North German Confederation. In a subsequent Franco-Prussian War, the Prussians and their German allies defeated France, and proclaimed the German Empire in 1871.[26]

In the years following unification, German society was radically changed by numerous processes, including industrialization, rationalization, secularization and the rise of capitalism.[32] German power increased considerably and numerous German colonies were established overseas.[33] During this time, the German population expanded considerably, and many emigrated to other countries, contributing to the growth of the German diaspora. Competition for colonies between the French, British and German empires contributed to sparking World War I, in which the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires formed the Central Powers in opposition to the Allies of World War I. In the aftermath of the war, which was won by the Allies, the German Empire and Austria-Hungary were both dissolved and partially partitioned, resulting in millions of Germans becoming ethnic minorities in other countries.[34] Rulers of numerous German states, including the German emperor Wilhelm II, were overthrown, and the Weimar Republic was proclaimed. The Germans of Austria-Hungary proclaimed the Republic of German-Austria, and sought to be incorporated into the German state, but this was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles and Treaty of Saint-Germain.[33]

What many Germans saw as the "humiliation of Versailles",[35] continuing traditions of authoritarian and antisemitic ideologies,[32] and the Great Depression all contributed to the rise of Austrian-born Adolf Hitler, who established the totalitarian state of Nazi Germany and started World War II in his quest to subjugate Europe. Six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, about one million of them at Auschwitz concentration camp. The war resulted in widespread destruction and the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians, while the German state was partitioned. About 12 million Germans had to flee or were expelled from Eastern Europe.[36] The devastations also did much damage to the identity and reputation of the Germans.[34] As a result of the war, German identity became less nationalistic than what is was in the past.[35]

The German states of West Germany and East Germany became focal points of the Cold War, but were reunified in 1990. Although there were fears that the reunified Germany might resume nationalist politics, the country is today widely regarded as a "stablizing actor in the heart of Europe" and a "promoter of democratic integration".[35]

Language

German is the native language of most Germans. It is the key marker of German ethnic identity.[2][24] German is a West Germanic language closely related to Frisian, English and Dutch.[2] The main dialects of German are High German and Low German. Standard literary German is based on High German, and is the first or second language of most Germans, but notably not the Volga Germans.[22]

Culture

The Germans are marked by great regional diversity, which makes identifying a single German culture quite difficult.[37] The arts and sciences have for centuries been an important part of German identity.[38] The Age of Enlightenment and the Romantic era saw a notable flourishing of German culture. Germans of this period who contributed significantly to the arts and sciences include the writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Johann Gottfried Herder, Friedrich Hölderlin, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Heinrich Heine, Novalis and the Brothers Grimm, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, the painter Caspar David Friedrich, and the composers Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert, Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner.[37]

Popular German dishes include brown bread and stew. Germans consume a high amount alcohol, particularly beer, compared to other European peoples. Obesity is relatively widespread among Germans.[37]

Carnival is an important part of German culture, particularly in Southern Germany. An important German festival is the Oktoberfest.[37]

A steadily shrinking majority of Germans are Christians. About a third are Roman Catholics, while one third adheres to Protestantism. Another third does not profess any religion.[24] Christian holidays such as Christmas and Easter are celebrated by many Germans.[6] The number of Muslims is growing.[6] There is also a notable Jewish community, which was decimated in the Holocaust.[39] Remembering the Holocaust is an important part of German culture.[32]

Geographic distribution

It is estimated that there are between 100 and 150 million Germans today, most of whom live in Germany, where they constitute the majority of the population.[3] There are also sizable populations of Germans in Austria, Switzerland, the United States, Brazil, France, Kazakhstan, Russia, Argentina, Canada, Poland, Italy, Hungary, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Paraguay and Namibia.[4][5] German-speaking peoples such as the Austrians and the German-speaking Swiss are sometimes referred to by scholars as Germans, although most of them do not identify as such.[2][3]

| Country | Estimated populations of Germans |

|---|---|

| c. 75,000,000[2][3] | |

| c. 7,600,000 (disputed)[4] | |

| c. 5,000,000[5] | |

| c. 4,200,000 (disputed)[4] | |

| c. 3,000,000[5] | |

| c. 1,200,000[4] | |

| c. 900,000[4] | |

| c. 840,000[4] | |

| c. 700,000[4] | |

| c. 500,000[5] | |

| c. 450,000[5] | |

| c. 280,000[4] | |

| c. 250,000[4] | |

| c. 170,000[5] | |

| c. 110,000[5] | |

| c. 100,000[5] | |

| c. 75,000[5] | |

Identity

A German ethnic identity emerged among Germanic peoples of Central Europe in the 8th century.[8] These peoples came to be referred to by the High German term diutisc, which means "ethnic" or "relating to the people". The German endonym Deutsche is derived from this word.[2] In subsequent centuries, the German lands were relatively decentralized, leading to the maintenance of a number of strong regional identities.[26][27]

The German nationalist movement emerged among German intellectuals in the late 18th century. They saw the Germans as a people united by language and advocated the unification of all Germans into a single nation state, which was partially achieved in 1871. By the late 19th and early 20th century, German identity came to be defined by a shared descent, culture, and history.[11] Völkisch elements identified Germanness with "a shared Christian heritage" and "biological essence", to the exclusion of the notable Jewish minority.[40] After the Holocaust and the downfall of Nazism, "any confident sense of Germanness had become suspect, if not impossible".[41] East Germany and West Germany both sought to build up an identity on historical or ideological lines, distancing themselves both from the Nazi past and each other.[41] After German reunification in 1990, the political discourse was characterized by the idea of a "shared, ethnoculturally defined Germanness", and the general climate became increasingly xenophobic during the 1990s.[41] Today, discussion on Germanness may stress various aspects, such as commitment to pluralism and the German constitution (constitutional patriotism),[42] or the notion of a Kulturnation (nation sharing a common culture).[43] The German language remains the primary criterion of modern German identity.[11]

See also

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Die Deutschen, ZDF's documentary television series

- Anti-German sentiment

- Persecution of Germans

References

- Moser 2011, p. 171.

- Haarmann 2015, p. 313.

- Moser 2011, pp. 171-172.

- Haarmann 2015, p. 313. "Populations of Germans live elsewhere in Central and Western Europe, with the largest communities in Austria (7.6 million), Switzerland (4.2 million), France (1.2 million), Kazakhstan (900,000), Russia (840,000), Poland (700,000), Italy (280,000), and Hungary (250,000)."

- Moser 2011, pp. 171-172. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... The largest populations outside of these countries are found in the United States (5 million), Brazil (3 million), the former Soviet Union (2 million), Argentina (500,000), Canada (450,000), Spain (170,000), Australia (110,000), the United Kingdom (100,000), and South Africa (75,000)."

- Moser 2011, p. 176.

- Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz (2003). The Making of a Language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 449. ISBN 311017099X. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

The Germanic [peoples] still include: Englishmen, Dutchmen, Germans, Danes, Swedes, Saxons. Therefore, [in the same way] as Poles, Russians, Czechs, Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians belong to the Slavic [peoples]...

; Minahan 2000, p. 769. "Germanic nations:... Germans..." - Haarmann 2015, p. 313. "Germans are a Germanic (or Teutonic) people that are indigenous to Central Europe... Germanic tribes have inhabited Central Europe since at least Roman times, but it was not until the early Middle Ages that a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge."

- Moser 2011, p. 171. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... Estimates of the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 million to 150 million...

- Minahan 2000, p. 288. "The Germans are an ancient ethnic group, the basic stock in the composition of the peoples of Germany... The Germans include a number of important national groups, including the Bavarians, Rhinelanders, Saxons, and Swabians. The standard language of the Germans, called Deutsch or Hochdeutsch (High German), is spoken as the first or second language by all the German peoples in Europe except some of the Volga Germans in Russia."

- Moser 2011, p. 172. "German identity developed through a long historical process that led, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to the definition of the German nation as both a community of descent (Volksgemeinschaft) and shared culture and experience. Today, the German language is the primary though not exclusive criterion of German identity."

- Haarmann 2015, p. 313. "After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of national unity as Germans began to evolve in the eighteenth century, and the German language became a key marker of national identity."

- "Obtaining German Citizenship".; Alois Angleitner; Fritz Ostendorf; Oliver P. John (1990). "Towards a taxonomy of personality descriptors in German: A psycho‐lexical study".; "Who is a German?". The Economist. 3 April 1997.; David Danelo (12 May 2015). "Germany in the 21st Century, Part III: Who is a German". Foreign Policy Research Institute.

- "German". Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 733. ISBN 0199571120.

- "German". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Germans". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Germans". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 613. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001. ISBN 9780191735257.

- Todd, Malcolm (2004b). "Germans and Germanic Invasions". In Fagan, Brian M. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 250–251. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195076189.001.0001. ISBN 9780199891085.

- Wells, Peter S. (2010). "Germans". In Gagarin, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195388398.

- Hoad, T. F. (2003). "German". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001. ISBN 9780192830982. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Heather, Peter. "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Within the boundaries of present-day Germany... Germanic peoples such as the eastern Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringians, Alemanni, and Bavarians—all speaking West Germanic dialects—had merged Germanic and borrowed Roman cultural features. It was among these groups that a German language and ethnic identity would gradually develop during the Middle Ages.

- Minahan 2000, p. 288.

- Minahan 2000, pp. 288-289.

- Moser 2011, p. 172.

- Haarmann 2015, pp. 313-314.

- Haarmann 2015, p. 314.

- Minahan 2000, pp. 289-290.

- Moser 2011, p. 173.

- Minahan 2000, p. 290.

- Minahan 2000, pp. 290-291.

- Moser 2011, pp. 173-174.

- Moser 2011, p. 174.

- Minahan 2000, pp. 291-292.

- Haarmann 2015, pp. 314-315.

- Haarmann 2015, p. 316.

- Troebst, Stefan (2012). "The Discourse on Forced Migration and European Culture of Remembrance". The Hungarian Historical Review. 1 (3/4): 397–414. JSTOR 42568610.

- Moser 2011, pp. 176-177.

- Waldman & Mason 2005, pp. 334-335.

- Minahan 2000, p. 174.

- Rock 2019, p. 32.

- Rock 2019, p. 33.

- Rock 2019, pp. 33-34.

- Rock 2019, p. 34.

Bibliography

- Haarmann, Harald (2015). "Germans". In Danver, Steven (ed.). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. pp. 313–316. ISBN 1317464001.

- Moser, Johannes (2011). "Germans". In Cole, Jeffrey (ed.). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 171–177. ISBN 1598843028.

- Minahan, James (2000). "Germans". One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 287–294. ISBN 0313309841.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2005). "Germans". Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 330–335. ISBN 1438129181.

Further reading

- Craig, Gordon Alexander (1983). The Germans. New American Library. ISBN 0452006228.

- Elias, Norbert (1996). The Germans. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231105630.

- James, Harold (2000). A German Identity (2 ed.). Phoenix Press. ISBN 1842122045.

- Mallory, J. P. (1991). "Germans". In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson. pp. 84–87.

- Rock, Lena (2019). As German as Kafka: Identity and Singularity in German Literature around 1900 and 2000. Leuven University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvss3xg0. JSTOR j.ctvss3xg0.

- Todd, Malcolm (2004a). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405117142.

- Wells, Peter S. (2011). "The Ancient Germans". In Bonfante, Larissa (ed.). The Barbarians of Ancient Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–232. ISBN 978-0-521-19404-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Germans. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Germans |