Eureka Rebellion

The Eureka Rebellion occurred in 1854, involving gold miners in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, who revolted against the colonial authority of the United Kingdom. It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, which was fought between the rebels and the colonial forces of Australia on 3 December 1854 at Eureka Lead and named after a stockade structure built by miners in the lead-up to the conflict.[2] The rebellion resulted in at least 27 deaths and many injuries, the majority of casualties being rebels.

| Eureka Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

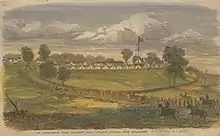

Eureka Stockade Riot by John Black Henderson (1854). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 276 | 190 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 killed |

22–60 killed (estimated)[1] 12+ wounded 120+ captured | ||||||

The rebellion was the culmination of a period of civil disobedience during the Victorian gold rush with miners objecting to the expense of a miner's licence, taxation via the licence without representation, and the actions of the government, the police and military.[3][4] The local rebellion grew from a Ballarat Reform League movement and culminated in the rebels erecting a crude battlement followed by a swift and deadly siege by the colonial forces.

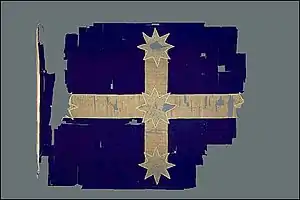

When the captured rebels faced trial in Melbourne, mass public support led to their release and resulted in the introduction of the Electoral Act 1856, which mandated suffrage for male colonists in the lower house in the Victorian parliament. This is considered the second instituted act of political democracy in Australia.[3] The Eureka Rebellion is controversially identified with the birth of democracy in Australia and interpreted by many as a political revolt.[5][6][7] A dedicated museum the Eureka Centre Ballarat has as its centrepiece a flag which the miners designed and swore allegiance to before the battle.

Location

In 1931, R. S. Reed claimed that "an old tree stump on the south side of Victoria Street, near Humffray Street, is the historic tree at which the pioneer diggers gathered in the days before the Eureka Stockade, to discuss their grievances against the officialdom of the time."[8] Reed called for the formation of a committee of citizens to "beautify the spot, and to preserve the tree stump" upon which Lalor addressed the assembled rebels during the oath swearing ceremony.[8] It was also reported the stump "has been securely fenced in, and the enclosed area is to be planted with floriferous trees. The spot is adjacent to Eureka, which is famed alike for the stockade fight and for the fact that the Welcome Nugget. (sold for £10,500) was discovered in 1858 within a stone's throw of it."[9] A report commissioned by the City of Ballarat in 2015 found that the most likely site of the rallies which led to the rebellion was 29 St. Paul's Way, Bakery Hill.[10] Given documentary evidence and its elevation, this was likely to be the site where speeches were made and the Eureka Flag was symbolically hoisted for the first time. As of 2018, the area is a carpark awaiting residential development.[11]

The precise site of the Stockade itself remains unknown,[12] but William Bramwell Withers described its location in 1870: 'It was an area of about an acre, rudely enclosed with slabs, and situated at the point where the Eureka Lead took its bend by the old Melbourne road, now called Eureka Street ... The Site ... lay about midway between what are now Stawell and Queen streets on the east and west, and close to Eureka Street on the south.'[13]

Background

Following the separation of Victoria from New South Wales on 1 July 1851, gold prospectors were offered 200 guineas for making payable discoveries within a 200-mile radius of Melbourne.[14] In August 1851 the news was received around the world that, on top of several earlier finds, Thomas Hiscock, 3 kilometres west of Buninyong (now Magpie, approximately 10 kilometres south of Eureka), had found still more deposits.[15] This led to gold fever taking hold as the population of the colony increased from 77,000 in 1851 to 198,496 in 1853.[16] Among this number was "a heavy sprinkling of ex-convicts, gamblers, thieves, rogues and vagabonds of all kinds."[17] The local authorities soon found themselves with fewer police and lacking the infrastructure needed to support the expansion of the mining industry. The number of public servants, factory and farm workers leaving for the goldfields to seek their fortune made for chronic labor shortages that needed to be resolved.

La Trobe introduces monthly mining tax as protests begin

On 16 August 1851, just days after Hiscock's lucky strike, Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe issued two proclamations that reserved all crown land rights to the goldfields and introduced a mining tax of 30 shillings per month, effective 1 September.[18] The universal mining tax was based on time stayed, rather than what was seen as the more equitable option, being an export duty levied only on gold found, meaning it was always designed to make life unprofitable for most prospectors.[19]

In the years leading up to the armed revolt there were several mass public meetings, and miner's delegations, with the earliest rally held on 26 August 1851 at Hiscock's Gully in Buninyong that attracted 40-50 miners protesting the new mining regulations and four resolutions to this end were passed.[20] The miners opposed government policies of oppression including the licence fee, [20] This first meeting was followed by dissent all across the colony's mining settlements. Even at this early stage there was said to be division between the "moral force" activists who favoured lawful, peaceful and democratic means, and those who advocated "physical force," who were later to gain the ascendancy, with some in attendance suggesting the miners exercise their right to revolution and take up arms against the governor who was irreverently viewed as a feather wearing, effeminate fop.[21]

First gold commissioner arrives in Ballarat

In mid September 1851, the first gold commissioner appointed by Governor Latrobe arrives in Ballarat.[22] At the beginning of December, there was discontent when it was announced that the licence fee would be raised to 3 pounds a month, effective 1 January 1852.[23] In Ballarat some miners became so agitated that they began to gather arms.[24] On 8 December, the rebellion continued to build up momentum with an anti mining tax banner put on public display at Forrest Creek.[25] The Great Meeting of Diggers takes place at Mount Alexander on 15 December 1851 and according to high end estimates, 20,000 miners demonstrate in a massive display of support for repealing the licence fee system.[26] Two days later it was announced by the governor that the planned one hundred per cent increase in the mining tax had been reversed. Nevertheless, the oppressive licence hunts continued and increased in frequency causing general dissent among the diggers.[27] In addition, Weston Bate noted that at the Ballarat diggings there was strong opposition to the strict liquor licensing laws imposed by the government.

Despite the high turnover in population on the goldfields, discontent continues to simmer throughout 1852. On 2 September 1852 Government House receives a petition from the people of Bendigo drawing attention to the need for improvements in the road from Melbourne. The lack of police protection was also a major issue for the protesting miners. On 14 August 1852 an affray breaks out among 150 men over land rights in Bendigo. An inquiry recommends an increase in police numbers in the colony's mining settlements. Around this time the first gold deposits at the Eureka lead in Ballarat are found.[28] In October 1852 at Lever Flat near Bendigo the miners would attempt to respond to rising crime levels by forming a "Mutual Protection Association" with a pledge to withhold the licence fee and build detention centres so as nightly armed patrols could begin, with privateers dispensing summary justice to those deeply suspected of crime. That month Government House receives a petition from Lever Flat, Forrest Creek and Mount Alexander, on the subject of policing levels, as the colony continues to strain under the weight of the Victorian gold rush which was begun. On 25 November 1852 there was an assault by a mob of miners on a police officer by men who wrongly believed they were obliged to take out a whole month's subscription for seven days in the diggings, at Oven's field, Bendigo.

Bendigo petition and the Red Ribbon Movement

Throughout 1853 the disquiet on the goldfields continues with public meetings held in Castlemaine, Heathcote and Bendigo.[29] On 3 February 1853 after a policeman accidentally caused the death of William Guest, assistant commissioner James Clow had to diffuse a difficult situation with a promise to conduct an inquiry into the circumstances, as a group of one thousand miners at Reid's Creek over runs the government camp and relieved the constabulary of their sidearms and weapons, as a cache is destroyed by angry miners. George Black assisted Dr John Owens in chairing a public meeting held at Ovens field on 11 February 1853 to protest that the alleged wrongful death of William Guest had not been fully investigated. In June the Anti-Gold Licence Association was formed at a meeting in Bendigo where 23,000 signatures were collected for a mass petition, including 8,000 from the mining settlement at McIvor.[30] On 2 July 1853 the police are assaulted in the vicinity of an anti-licence meeting at the Sandhurst gold field in Bendigo with rocks being thrown as they escort an intoxicated miner to the holding cells. On 16 July 1853 an anti-licence demonstration in Sandhurst attracts 6000 people who also raised the issue of lack of electoral rights. The high commissioner of the goldfields, William Wright, advised the governor of his support for an export duty on gold found, rather than the current universal tax on all prospectors based on time stayed. On 3 August, the Bendigo petition is placed before Governor LaTrobe.

On 13 August, the Bendigo 'diggers flag' is unfurled at a rally at View Point, Sandhurst. It was reported that the miners paraded under the flags of several nations, including the Irish tricolour, the satire of Scotland, the Union Jack, revolutionary French and German flags, and the Stars and Stripes. The delegates returned from Melbourne informed the estimated crowd of between 10,000–12,000 people of the failure of the Bendigo petition. On 20 August 1853 just as an angry mob of 500-600 miners who went to assemble outside the Government Camp at Waranga, the authorities caved in as a convenient legal technicality was found to release some mining licence evaders. A meeting in Beechworth calls for a reduction of the licence fee to ten shillings and voting rights for the mining settlements. La Trobe responds to the miner's July petition with no plans to address their grievances forthcoming. Another larger rally attended of 20,000 people is held at Hospital Hill in Bendigo on 23 August 1953, which resolves to support a mining tariff fixed at 10 shillings a month.[31][32] After the second multinational style assembly at View Point on 27 August, the Red Ribbon Movement spreads to the Victorian goldfields. Miners were asked to wear a red ribbon to demonstrate their opposition to and non payment of the licence fee.[33][34] The unlawful but peaceful strategy of the Red Ribbon Movement was for supporters to only hand over the agreed sum of only 10 shillings, and allow their numbers in custody to cause an administrative meltdown for the colonial authorities. The next day a procession of miners passes by the government camp with the sounds of bands and shouting and fifty pistol rounds, as an assembly of about 2,000 miners takes place. On 29 August 1853 assistant commissioner Robert Rede at Jones Creek, which along with Sandhurst were known hotbeds of activity for the Red Ribbon movement, counsels that a peaceful, political solution can still be found. In Ballarat activists offered to surround the guard tent to protect gold reserves amid rumours of a planned robbery.

A sitting of the goldfields committee of the Legislative Council in Melbourne on 6 September 1853 hears from goldfields activists Dr William Carr, W Fraser and William Jones. An Act for the Better Management of the Goldfield is passed, which upon receiving royal assent on 1 December, reduces the licence fee to 40 shillings for every 3 months. There is a sliding scale of fines in the order of 5, 10 and 15 pounds for repeat offenders, with goldfields residents required to carry their permits which are open for immediate inspection at all times which further incensed the miners. However the fee reduction is welcomed by the malcontents, thereby temporarily relieving tensions in the colony. In November the select committee bill proposes a licence fee of 1 pound for one month, 2 pounds for three months, 3 for six months and 5 pounds for 12 months, and extending the franchise and land rights to the miners. Government House amends the scheme by increasing the 6 months licence to 4 pounds, with a fee of 8 pounds for 12 months.

Another crowd of 2,000-3,000 attended an anti-licence rally at View Point on 3 December 1953. There again on the 31 December 1854, about 500 individuals gathered to elect a so-called "Diggers Congress."

Legislative Council calls for Commission of Inquiry

Governor LaTrobe cancels the September mining tax collections and supports a Commission of Inquiry into goldfields grievances. The Legislative Council is asked to consider a proposal to abolish the licence fee in return for a royalty on gold and a nominal charge for the maintaining the police service.[35] In November it was resolved by the Legislative Council that the licence fee be reinstated on a sliding scale of 1 pound per month, 2 pounds per three months, 4 pounds for six months, and 8 pounds for 12 months. License evasion was punishable by increasing fines of 5, 15 and 30 pounds, with serial offenders liable to be sentenced to a term of imprisonment.

Licence inspections, which were treated as such great sport by mounted officials, known to the miners by the warning call "Traps" or "Joes," were now able to take place at any time without notice.[36][37] The latter sobriquet was a reference to the governor whose proclamations posted around the goldfields were signed and sealed "Walter Joseph Latrobe."[38] Many of the police were former convicts from Tasmania who would get a fifty per cent commission from any fines imposed and were prone to resorting to brutal and violent means.[39][40] Miners were often arrested for not carrying their licences on their person, as they often left them in their tents due to the typically wet and dirty conditions in the mines, then subjected to such indignities as being chained to trees and logs overnight.[41] The impost was most felt by the greater number who were finding the mining tax untenable without anymore significant discoveries.

In March 1854, Governor LaTrobe sends a reform package to the Legislative Council which is adopted and sent to London for the approval of the British Parliament and features a scheme whereby the franchise is granted to miners holding a 12 month permit.[42]

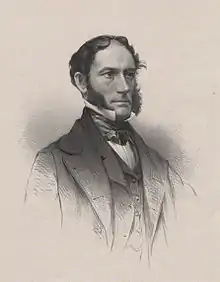

Charles Hotham sworn in as governor

La Trobe's replacement as lieutenant-governor, Charles Hotham, who would have preferred to be serving in the Crimean War, takes up his commission in Victoria on 22 June 1854.[43] In the capital, His Excellency is worried as the labour drain to the goldfields continues as more and more factory and farm hands leave their jobs to try their hand at prospecting, and commissions Robert Rede to conduct a weekly cycle of licence hunts with the introduction of a strict enforcement system, which it was hoped, would cause the exodus to the goldfields to be reversed.[44] In August 1854, the Governor and Lady Hotham are well received in Ballarat during a tour of the Victorian goldfields. In September Governor Hotham orders more frequent twice weekly licence hunts with more than half of the prospectors on the goldfields remaining non compliant with the regulations.[45][46]

According to Carboni's recollections of law enforcement in Ballarat: "Up to the middle of September the search for licences happened once a month; at most, twice: perhaps once a week on the Gravel Pits. Now, licence-hunting became the order of the day. Twice a week on every line, and the more the diggers felt annoyed at it, the more our Camp officials persisted in goading us...in October and November, when the weather allowed it, the Camp rode from the hunt every alternate day."[47]

Again the Bendigo miners responded to an increase in the frequency of twice weekly licence hunts with threats of armed rebellion.[48]

Murder of James Scobie and the burning of Bentley's Hotel

A few weeks later in October, the murder of James Scobie outside the Eureka Hotel, and the story of a disabled servant named Johannes Gregorious, who was in the employ of the parish priest Father Smyth of St Alipius chapel, when he was subjected to police brutality and false arrest for licence evasion even though he was exempt from the requirement,[49] was the beginning of the end for those opposed to physical force in the mining tax protest movement. A subsequently discredited coronial inquest finds no evidence of culpability by the Bently Hotel owners for the fatal injuries, amid allegations the Magistrate D’Ewes had a conflict of interest presiding over a case involving the prosecution of Bently, said to be a friend and indebted business partner.[50][51] A mass meeting of predominantly Catholic miners takes place on Bakery Hill in protest over the treatment of Father Smyth's servant on 15 October. Two days later, amid the uproar over the acquittal, a meeting of approximately 10,000 men takes place near the Eureka Hotel in protest. It is said that as things turned ugly the gold receiver John Green initially tried to read the riot act but was apparently too overawed, as the hotel is set alight and commissioner Rede is pelted with eggs and the available security forces are unable to restore order.[52][53]

Hotham would write is a despatch stating that "I lost no time in making such dispositions as I concluded would enable the authorities to maintain the integrity of the law; and within four days 450 military and police were on the ground, commanded by an officer in whom I had confidence, and who was instructed to enforce order and quiet, support the civil authority in the arrest of the ringleaders and to use force, whenever legally called upon to do so, without regard to the consequences which might ensue."[54] On 21 October, arrests over the rioting begin as Andrew McIntyre and Thomas Fletcher are taken into custody in relation to the Eureka Hotel arson attack.[55] A third man, Westerby, is also indicted. A committee meeting of miners on Bakery Hill agrees to indemnify the bail sureties for McIntyre and Fletcher. As a large mob approaches the government camp, the two men were hurriedly released under their own recognisances, and whisked away to the sound of gunfire from pistols.[56]

As if to stir the pot further, Carboni recalls that around this time the following two reward notices were plastered around Ballarat. One offered a 500 pound reward for information leading to an arrest in the James Scobie case. The other announced the reward for more information in relation to the Bank of Victoria heist in Ballarat that was carried out by robbers wearing black crepe paper masks had been increased from 500 to 1,600 pounds.[57][58] A miner's delegation is received by commissioner Rede on 23 October who hears that the police officers involved in the arrest of Gregorious should be dismissed. Two days later, a meeting led by Timothy Hayes and John Manning, hears reports from the deputies sent to negotiate with Rede. The meeting resolves to petition the Governor seeking a retrial of Gregorius and the reassignment of the reviled assistant commissioner Johnston away from Ballarat.[59]

On 27 October Captain Thomas lays contingency plans for the defence of the government outpost. On 30 October Governor Hotham appoints a board of enquiry into the murder of James Scobie, which will sit in Ballarat on the 2nd and the 10th November. The panel includes Melbourne magistrate Evelyn Sturt, assisted by his local magistrate Hackett and William McCrea. After receiving representations from the US consul, Governor Hotham releases James Tarleton from custody.[60] The inquiry into the Ballarat rioting concludes with a statement being made on 10 November in the name of the Ballarat Reform League - which by this stage apparently had a steering committee for some weeks - that was signed by John Humffray, Fredrick Vern, Henry Ross and Samuel Irwin of the Geelong Advertiser. The final report agreed with the League's submission blaming the government camp for unsatisfactory state of affairs. The recommendation that Magistrate Dewes and Sergeant Major-Milne of the constabluary should be dismissed was duly acted upon.[61]

At a gathering of 5,000 miners in Bendigo on 1 November a plan is drawn up to organise the diggers at all the mining settlements, as speakers openly advocating physical force address the crowd.

At a public meeting held on 11 November 1854 it is formally moved at a public meeting on Bakery Hill that the Ballarat Reform League be established, at a meeting of up to 10,000 people. The political ideals enunciated by the approved charter were inspired by 19th century English Chartism and the right to vote, and supports the immediate abolition of all mining and trading licences, and the end of the gold commission.

Governor Hotham sends a message to England on 16 November which reveals his intention to establish an inquiry into goldfields grievances. Notes to the royal commissioners had already been made on 6 November, where Hotham stated his opposition to an export duty on gold replacing the universal mining tax. W.C. Haines MLC was to be the chairman, serving alongside lawmakers John Fawkner, John O'Shanassy, William Westgarth as well as chief gold commissioner William Wright.

The James Scobie murder trial ends on 18 November 1854 with the accused James Bently, Thomas Farrell and William Hance being convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to three years hard labour on a road crew. Catherine Bently was acquitted. Two days later the miners Westerby, Fletcher and McIntyre are convicted for the burning of the Eureka Hotel and in turn were sentenced to jail terms of six, four and three months. The jury recommend the prerogative of mercy be involved, and noted that they held the local authorities in Ballarat responsible for the loss of property. A week later, a Ballarat reform league delegation including Humffray meets with Governor Hotham, Attorney General Stawell and Colonial Secretary Foster, to negotiate the release of the three Eureka Hotel rioters. Hotham declared that he would take a stand on the word ‘demand,’ believing instead that due process had been done. Father Smyth informs Commissioner Rede in confidence that he believes the miners may be about to march on the government outpost.[62]

Ballarat Reform League meetings

On Saturday, 11 November 1854 a crowd estimated at more than 10,000 miners gathered at Bakery Hill, directly opposite the government encampment. At this meeting, the Ballarat Reform League was created, under the chairmanship of Chartist John Basson Humffray. Several other Reform League leaders, including Kennedy and Holyoake, had been involved with the Chartist movement in England. Many of the miners had past involvement in the Chartist movement and the social upheavals in Britain, Ireland, and continental Europe during the 1840s.

In setting its goals, the Ballarat Reform League[63] used the first five of the British Chartist movement's principles as set out in the People's Charter of 1838.[64] They did not adopt or agitate for the Chartist's sixth principle, secret ballots. The meeting passed a resolution "that it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called on to obey, that taxation without representation is tyranny." The meeting also resolved to secede from the United Kingdom if the situation did not improve.[65]

Throughout the following weeks, the League sought to negotiate with Commissioner Robert Rede and the Governor of Victoria, Sir Charles Hotham, on the specific matters relating to Bentley and the death of Scobie, the men being tried for the burning of the Eureka Hotel, the broader issues of abolition of the licence, suffrage and democratic representation of the gold fields, and disbanding of the Gold Commission. On 16 November 1854 Governor Hotham appointed a Royal Commission to address the gold miners' problems and grievances. Geofffrey Blainey has stated that: "It was perhaps the most generous concession offered by a governor to a major opponent in the history of Australia up to that time. The members of the commission were appointed before Eureka...they were men who were likely to be sympathetic to the diggers." However Commissioner Rede, rather than hear miners' grievances, increased the police presence in the gold fields and summoned reinforcements from Melbourne. Many historians (most notably Manning Clark) attribute this to his belief in his right to exert authority over the "rabble."

The next day a "monster" meeting attracting over a crowd of around 10,000 is held, as the aggrieved miners hear from their deputies news of the unsuccessful outcome of their meeting with Governor Hotham. As the Eureka flag flies over the platform for the first time a number of mining licences are incinerated by the true rebels led by Timothy Hayes shouting "Are you ready to die?", and Fredrick Vern, who has been accused of abandoning the garrison four days later as soon as the danger arrived, with suspicions he could have been a double agent. Local clergyman Theophilus Taylor recorded his impressions.

Today Ballaarat is thrown into great excitement by a monster meeting of the diggers, convened for the purpose of protesting against the Gold Digging Licences and their alleged grievances. At the head of the meeting appeared two Catholic priests Fathers Downing and Smith[Smyth]. It was resolved to resist government by burning licences which was done to a considerable extent.[66]

Rede responded by ordering police to conduct a licence search on 30 November. Eight defaulters were arrested, and most of the military resources available had to be summoned to extricate the arresting officers from the angry mob that had assembled.[67]

Clergyman Taylor's account identified the rising tension.

This morning the police, as usual, made enquiries for Licences. They were resisted and a riot was raised. In consequence the troopers and military were called out and matters assumed a big serious aspect. A few were taken up and for a few hours the excitement subsided. Afternoon the mob had assembled and by evening had organised themselves into a gang of rebels.[68]

This raid prompted a change in the leadership of the Reform League, to people who argued in favour of 'physical force' rather than the 'moral force' championed by Humffray and the old leadership.[69]

Escalating violence as military convoy looted

Within 24 hours more British redcoats arrive as the 12th regiment arrives to reinforce the Ballarat town garrison. As they move alongside where the Eureka Stockade was about to be erected, there was physical force used as a drummer boy John Egan and several other members of the convoy are attacked by a mob looking to loot the wagons.[70] Tradition variously had it that Egan was either killed there are then, or alternatively, that he was the first casualty of the fighting on the day of the battle. However his grave in Old Ballarat Cemetery was removed in 2001, as a result of research carried out by Eureka author Dorothy Wickham, which appears to show that Egan in fact survived and died in Sydney in 1860.[71]

Battle of the Eureka Stockade

British colonial forces order of battle

Foot police reinforcements arrived in Ballarat on 19 October 1854 with a further detachment of the 40th Regiment a few days behind. By the beginning of December, the police contingent at Ballarat had been joined and surpassed in number by soldiers from British Army garrisons in Victoria, including detachments from the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot and 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment of Foot.[72] The strength of the various units in the government camp was: 40th regiment (infantry): 87 men; 40th regiment (mounted): 30 men; 12th regiment (infantry): 65 men; Mounted police: 70 men; and the Foot police: 24 men.

Commissioner Rede's plan was to send the combined military police formation of 276 men under the command of Captain John Thomas to attack the Eureka Stockade, when the rebel garrison was observed to be at a low water mark, with complete surprise at around 3.30 am. The British commander used bugle calls to coordinate his forces. The 40th regiment was to provide covering fire from one end, with mounted police covering the flanks. Enemy contact began at approximately 150 yards, as the two columns of regular infantry and the contingent of foot police moved into position.

Paramilitary mobilisation and swearing allegiance to the Southern Cross

As none of the other leading lights in the protest movement were in attendance amid the rising tide of anger and resentment amongst the miners, a more militant leader, Peter Lalor, who at his first public appearance at the 17 November meeting moved that a central rebel executive be formed, [73] took the initiave and mounted a stump armed with a rifle to give a speech. Lalor would proclaim "liberty" and call for volunteers to step forward and be sworn into companies and captains were appointed.[74] Near the base of the flagpole Lalor knelt down with his head uncovered, pointed his right hand to the Eureka Flag, and swore to the affirmation of his fellow demonstrators: "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties."[75]

In a despatch dated 20 December 1854 Lieutenant-Governor Charles Hotham said: "The disaffected miners...held a meeting whereat the Australian flag of independence was solemnly consecrated and vows offered for its defence."[76]

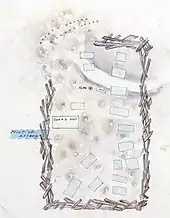

Fortification of the Eureka lead

After the oath swearing ceremony the rebels marched in double file from Bakery Hill to the Eureka gold reef behind the Eureka Flag being carried by the rebel captain Henry Ross, where construction of the stockade took place between 30 November and 2 December.[77][78] The stockade itself was a ramshackle affair that Raffaello Carboni in his 1855 memoirs described as "higgledy piggledy."[79] It was erected around an existing area of working mines,[80] and consisted of diagonal wooden spikes made from materials including pit props and over turned horse carts around area which was said to be one acre; however that is difficult to reconcile with other estimates that have the metric dimensions of the stockade as being around 100 feet x 200 feet.[81]

According to Lalor the stockade "was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence."[82] However Peter FitzSimons asserts that Lalor may have downplayed the fact that the Eureka Stockade may have been intended as something of a fortress, at a time when "it was very much in his interests" to do so.[83] The construction work was overseen by Vern, who had apparently received instruction in military methods. Lynch wrote that his "military learning comprehended the whole system of warfare ... fortification was his strong point." Les Blake has noted how other descriptions of the stockade "rather contradicted" Lalor's recollection of it being a simple fence after the fall of the stockade.[84] Testimony was heard at the high treason trials for the Eureka rebels that the stockade was four to seven feet high in places, and was unable to be negotiated on horseback without being reduced.[85]

Lieutenant-Governor Hotham's fear was that the "network of rabbit burrows" on the goldfields would prove readily defensible as his forces "on the rough pot-holed ground were would be unable to advance in regular formation and would be picked off easily be snipers", considerations that were part of the reasoning behind the decision to stealthily move into position for an early morning surprise attack.[86] Carboni details the rebel dispositions along: "The shepherds' holes inside the lower part of the stockade had been turned into rifle-pits, and were now occupied by Californians of the I.C. Rangers' Brigade, some twenty or thirty in all, who had kept watch at the 'outposts' during the night."[87]

However the location of the stockade has been described as "appalling from a defensive point of view" situated as it was on "a gentle slope, which exposed a sizeable portion of its interior to fire from nearby high ground."[88] A detachment of 800 men which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" under the commander in chief of the British forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle, who had also saw action during the 1798 Irish rebellion, would arrive after the insurgency had been put down.

The rebels sent out scouts and established picket lines in order to have advance warning of Rede's movements. Messengers were dispatched to other mining settlements including Bendigo and Creswick, requesting reinforcements for the Bakery Hill rebellion.[89] On 1 December the "moral force" faction lead by J.B. Humffray withdrew from the protest movement, as the men of violence moved into the ascendancy. The rebels continued to fortify their position, as 300-400 men arrive from Creswick's Creek to join the struggle. Carboni recalls they were: "dirty and ragged, and proved the greatest nuisance. One of them, Michael Tuehy, behaved valiantly."[90]

The arrival of these reinforcements requires the dispatch of foraging parties, leaving a garrison of around 200 men behind. Teddy Shanahan, a merchant whose store on the Eureka golf reef had been engulfed by the stockade, recalls the rebels immediately became very short on food, drink, and accommodation, and that by 2nd December: "Lalor was in charge, but large numbers of the men were constantly going out of the Stockade, and as the majority got drunk, they never came back ... The 500 or 600 from Creswick had nothing to eat, and they, too, went down to the Main Road that night ... Lalor seeing that none would be left if things went on, he gave orders to shoot any man who left."[91]

During the 2 December, the peak rebel force of up to 1,500 insurgents trained in and around the rebel camp. At around 4pm, a contingent of 200 Americans under James McGill arrived. Styled as "The Independent Californian Rangers’ Revolver Brigade", they were had horses and were equipped with sidearms and Mexican knives. In a fateful decision, McGill decided to take most of his two hundred Californian Rangers away from the stockade to intercept rumoured British reinforcements coming from Melbourne. That night many of the miners went back to their own tents after the traditional Saturday night carousing, with the assumption that the Queen's military forces would not be sent to attack on the Sunday the Sabbath day. A small contingent of miners remained at the stockade overnight, which the spies reported to Rede. Common estimates for the size of the garrison at the time of the attack on 3 December range from 120-150 men.

According to Lalor's best estimates: "There were about 70 men possessing guns, 30 with pikes and 30 with pistols, but many had no more than one or two rounds of ammunition. Their coolness and bravery were admirable when it is considered that the odds were 3 to 1 against." Lalor's command was porous, riddled with informants, and Commissioner Rede was kept well advised of his movements, particularly through the work of double agents Goodenough and Andrews who were embedded in the rebel camp.

On the eve of the battle Father Smyth issued a plea for Catholics to down their arms and attend mass the following day.

Initially outnumbering the government camp considerably, Lalor had already devised a strategy where, "if the government forces come to attack us, we should meet them on the Gravel Pits, and if compelled, we should retreat by the heights to the old Canadian Gully, and there we shall make our final stand."[92] On being brought to battle that day, Lalor stated: "we would have retreated, but it was then too late."[93]

Vinegar Hill blunder: Irish dimension factors in dwindling numbers at stockade

The Argus newspaper of 4 December 1854 reported that the Union Jack "had" to be hoisted underneath the Eureka flag at the stockade, and that both flags were in the possession of the foot police.[94] Some have questioned whether this sole contemporaneous report of the otherwise unaccounted for Union Jack known as the Eureka Jack being present is accurate.[95] In support of this alternative scenario it has been theorised that the hoisting of a Union Jack at the stockade was possibly an 11th hour response to the divided loyalties among the heterogeneous rebel force which was in the process of melting away.[96] At one point 1,500 of 17,280 men in Ballarat were present, with only 150 taking part in the battle. Lalor's choice of password for the night of 2 December – "Vinegar Hill"[97][98][99][100] – causing support for the rebellion to fall away among those who were otherwise disposed to resist the military, as word spread that the question of Irish home rule had become involved. One suvivor of the battle stated that "the collapse of the rising at Ballarat may be regarded as mainly attributable to the password given by Lalor on the night before the assault." Asked by one of his subordinates for the "night pass", he gave "Vinegar Hill," the site of a battle during the 1798 Irish rebellion. The 1804 Castle Hill uprising, also known as the second battle of Vinegar Hill, was the site of a rebellion by convicts in the colony of New South Wales, involving mainly Irish transportees some of whom were at Vinegar Hill.[101] William Craig in his memoirs recalled that "Many at Ballaarat, who were disposed before that to resist the military, now quietly withdrew from the movement." John Lynch recalls that: "On the afternoon of Saturday we had a force of seven hundred men on whom we thought we could rely." However there was a false alarm from the picket line during the night. The subsequent roll call revealed there had been a sizable desertion that Lynch says "ought to have been seriously considered, but it was not." There were miners from Bendigo, Forrest Creek, and Creswick that marched to Ballarat to take part in the armed struggle. The latter contingent was said to number a thousand men "but when the news circulated that Irish independence had crept into the movement, almost all turned back." Peter FitzSimons points out that although the number of reinforcements converging on Ballarat was probably closer to 500, there is no doubt that as a result of the choice of password "the Stockade is denied many strong-armed men because of the feeling that the Irish have taken over."[102] Ballarat born historian William Withers notes that: "Lalor, it is said, gave 'Vinegar Hill' as the night's pass-word, but neither he nor his adherents expected that the fatal action of Sunday was coming, and some of his followers, incited by the sinister omen of the pass-word, abandoned that night what they saw was a badly organised and not very hopeful movement."[103]

There is another theory advanced by Gregory Blake, military historian and author of Eureka Stockade: A Ferocious and Bloody Battle, who concedes that two flags may have been flown on the day of the battle, as the miners were claiming to be defending their British rights.

In a signed contemporaneous affidavit dated 7 December 1854, Private Hugh King, who was at the battle serving with the 40th regiment, recalled that:

"...three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me. When the fire was opened on us we received orders to fire. I saw some of the 40th wounded lying on the ground but I cannot say that it was before the fire on both sides. I think some of the men in the stockade should-they had a flag flying in the stockade; it was a white cross of five stars on a blue ground. – flag was afterwards taken from one of the prisoners like a union jack – we fired and advanced on the stockade, when we jumped over, we were ordered to take all we could prisoners..."[104]

There was a further report in The Argus, 9 December 1854 edition, stating that Hugh King had given live testimony at the committal hearings for the Eureka rebels where he stated that the flag was found: "... rollen up in the breast of a[n] [unidentified] prisoner. He [King] advanced with the rest, firing as they advanced ... several shots were fired on them after they entered [the stockade]. He observed the prisoner [Hayes] brought down from a tent in custody."[105]

Blake leaves open the possibility that the flag being carried by the prisoner had been souvenired from the flag pole as the routed garrison was fleeing the stockade.[106]

It is certain that Irish-born people were strongly represented at the Eureka Stockade.[107] Historians have discovered that as well as the Irish comprising most of the rebels inside the stockade during the battle, the area where the defensive position was established was overwhelmingly populated by Irish miners. Professor Geoffrey Blainey has advanced the view that the white cross of the Eureka flag is "really an Irish cross rather than being [a] configuration of the Southern Cross".[108]

Fall of the Eureka Stockade

According to Gregory Blake, the fighting in Ballarat on 3 December 1854 was not one sided and full of indiscriminate murder by the colonial forces. In his memoirs one of Lalor's captains John Lynch recalls "some sharp shooting," and for at least 10 minutes the rebels offered stiff resistance, with ranged fire coming from the Eureka Stockade garrison such that Thomas's best formation the 40th regiment wavered and had to be rallied. Blake says this is "stark evidence of the effectiveness of the defender's fire."[109]

Contradictory accounts as to which side fired first shot

Despite Lalor's insistence that his standing orders to all but the riflemen was to engage at a distance of fifteen feet and that "the military fired the first volley," it appears as if the first shots came from the Eureka Stockade garrison.[110]

It has been claimed that Harry de Longville who was on pickett duty when the early morning shootout started and fired the first shot that was possibly intended to be a warning that the government forces were approaching. John O'Neill serving with the 40th regiment later recalled: "The party had not advanced three hundred yards before we were seen by a rebel sentry, who fired, not at our party, but to warn his party in the Stockade. He was on Black Hill. Captain Thomas turned his head in the direction of the shot, and said "We are seen. Forward, and steady men! Don't fire; let the insurgents fire first. You must wait for the sound of the bugle."[111]

A magistrate by the name of Charles Hackett, who had apparently had the singular distinction of being well liked by the miners in Ballarat, who had accompanied Captain Thomas gave sworn testimony that: "No shots were fired by the military or the police previous to shots being fired from the stockade." Hackett had accompanied the colonial forces in the hopes of being able to read the riot act to the insurgents but in the event had no time before the commencement for hostilities.[112]

According to another account by an American rebel on the other side: "The Fortieth regiment was advancing, but had not as yet discharged a shot. We could now see plainly the officer and hear his orders, when one of our men, Captain Burnette, stepped a little in front, elevated his rifle, took aim and fired. The officer fell. Captain Wise was his name. This was the first shot in the Ballarat war. It was said by many that the soldiers fired the first shot, but that is not true, as is well known to many."[113]

Withers gives an account by one of Lalor's lieutenants who stated: "The first shot was fired from our party, and the military answered by a volley at 100 paces distance."[114]

Lynch in his memoirs would recall the course of the battle saying: "A shot from our encampment was taken for a declaration of war, and instantaneously answered by a fusilade of musketry ... The advance of the infantry was arrested for a moment; our left was being unprotected, the troopers seized the advantage, wheeled round, and took us in the rear. We were then placed between two fires, and further resistance was useless."

In the area where first contact with the enemy was made Carboni also recounts: "Here a lad was really courageous with his bugle. He took up boldly his stand to the left of the gully and in front: the red-coats 'fell in' in their ranks to the right of this lad. The wounded on the ground behind must have numbered a dozen."[115]

Eureka Stockade garrison routed

Theophilus Taylor's account is succinct. "A company of troopers & military carried the war into the enemies camp. In a very short time numbers were shot and hundreds taken prisoner".[116]

As the rebels ran short of ammunition and the government forces resumed their advance, Carboni recalls that it was the pike men under who stood their ground suffered the heaviest casualties,[117] with Lalor ordering the musketeers to take refuge in the mine holes and saying "Pikemen, advance! Now for God's sake do your duty."[118]

During the height of the battle, Lalor had his left arm was shattered by bullet which later required amputation, and was hidden under some slabs before finally being secreted out of Ballarat to hide as an outlaw with supporters.[119][120] As Golden Point local Dr Timothy Doyle steadied himself to perform the operation, Lalor may have had one eye on history as he approached his loss of limb, saying "Courage, courage, take it off!." It was Doyle who in May 1953 exclaimed "Eureka!" as he found the first nuggets of gold around the area where the stockade appeared, by which the famous gold reef acquired its name.[121][122]

Stories tell how women ran forward and threw themselves over the injured to prevent further indiscriminate killing. The Commission of Inquiry would later say that it was "a needless as well as a ruthless sacrifice of human life indiscriminate of innocent or guilty, and after all resistance had disappeared." Early in the battle "Captain" Henry Ross was shot dead. Captain Charles Pasley, the second in command of the British forces, sickened by the carnage, saved a group of prisoners from being bayoneted and threatened to shoot any police or soldiers who continued with the slaughter. Pasley's valuable assistance was acknowledged in despatches printed and laid before the Victorian Legislative Council.[123]

Of those who had paid the ultimate price during the siege of the Eureka Stockade, the Geelong Advertiser reported that: "They all lay in a small space, with their faces upwards, looking like lead; several of them were still heaving, and at every rise of their breasts, the blood spouted out of their wounds, or just bubbled out and trickled away. One man, a stout-chested fine fellow ... had three contusions in the head, three strokes across the brow, a bayonet would in the throat ... and other wounds - I counted fifteen in that single carcase. Some were brining handerchiefs, others bed furniture and matting to cover up the faces of the dead. O God! sir, it was a sight for a Sabbath morn that, I humbly implore Heaven, may never be seen again. Poor women crying for absent husbands, and children frightened into quietness ... Some of the bodies might have been removed - I counted fifteen."[124]

Hotham would receive the news that the government forces had been victorious the same day, with the Attorney-General William Stawell of others waiting outside Saint James church where he was attending a service with colonial Secretary John Forster. He immediately set about firing up the government printing press to put out placards calling for support from among the colonists.[125]

Martial law was declared throughout the camp on Monday, with no lights allowed in any tent after 8 o'clock pm.[126] It was around this time an outbreak of gunfire reportedly occurred within the camp. Unrelated first-hand accounts state that variously, a woman, her infant child and several men were killed or wounded in an episode of indiscriminate shooting.[127][128]

Eureka Flag seized by Constable John King

During the battle, Constable John King volunteered to take the Eureka flag into police custody.[129] The report of Captain John Thomas dated 14 December 1854 mentioned: "the fact of the Flag belonging to the Insurgents (which had been nailed to the flagstaff) being captured by Constable King of the Force."[130] W. Bourke, a miner who lived about 250 yards from the Eureka Stockade, recalled that: "The police negotiated the wall of the Stockade on the south-west, and I then saw a policeman climb the flag pole. When up about 12 or 14 feet the pole broke, and he came down with a run." [131]

In his eyewitness account Carboni stated the Eureka Flag was then trailed in age old celebration of victory saying: "A wild 'hurrah!' burst out and 'the Southern Cross' was torn down, I should say, among their laughter, such as if it had been a prize from a May-pole...The red-coats were now ordered to 'fall in;' their bloody work was over, and were marched off, dragging with them the 'Southern Cross'."[132] The Geelong Advertiser reported that the flag "was carried by in triumph to the Camp, waved about in the air, then pitched from one to another, thrown down and trampled on."[133] The soldiers also danced around the flag on a pole that was "now a sadly tattered flag from which souvenir hunters had cut and torn pieces."[134] The morning after the battle "the policeman who captured the flag exhibited it to the curious and allowed such as so desired to tear off small portions of its ragged end to preserve as souvenirs."[135]

Estimates of the death toll

Of the soldiers and police, six were killed, including Captain Wise. According to Lalor's report, fourteen miners (mostly Irish) died inside the stockade and an additional eight died later from injuries they sustained. A further dozen were wounded but recovered. Three months after the Eureka Stockade, Peter Lalor wrote: "As the inhuman brutalities practised by the troops are so well known, it is unnecessary for me to repeat them. There were 34 digger casualties of which 22 died. The unusual proportion of the killed to the wounded, is owing to the butchery of the military and troopers after the surrender."[136] Carboni recalls the casualties being piled onto horse carts with the rebel dead destined for a mass grave. One hundred and fourteen diggers, some wounded, were marched off to the Government camp about two kilometres away, where they were kept in an overcrowded lock-up, before being moved to a more spacious barn on Monday morning. However the Exact numbers of deaths and injuries is difficult to determine as many miners "fled to the surrounding bush and it is likely a good many more died a lonely deate or suffered the agony of their wounds, hidden from the authorities for fear of repercussions." according to Eureka researcher and author Dr Dorothy Wickham. The official register of deaths in the Ballarat District Register shows 27 names associated with the stockade battle at Eureka.[137]

Reverend Taylor, in his account, estimated initially 100 deaths but reconsidered writing:

About 50 came at death by their folly. On the other side two soldiers killed and two officers wounded. The sight in the morning was truly appalling – Men lying dead slain by evil. The remedy is very lamentable but it appears it was necessary. It is hoped now rebellion will be checked.[116]

Historian Clare Wright quotes one source, Thomas Pierson, who noted in the margin to his diary time has proved that near 60 have died of the diggers in all. According to Wright, Captain Thomas estimated that 30 diggers died on the spot and many more died of their wounds subsequently. Even the Geelong Advertiser on 8 December 1854 stated that deaths were "more numerous than originally supposed".[1]

While it has been thought all the deaths at Eureka were men, research by historian Clare Wright details that at least one woman lost her life in the massacre. Wright's research details the important role of women on the goldfields and in the reform movement. Her book Forgotten Rebels of Eureka details how Charles Evans' diary describes a funeral for a woman who was mercilessly butchered by a mounted trooper while pleading for the life of her husband during the Eureka massacre. Her name and the fate and identity of her husband remain unknown.[138]

Alleged Declaration of Independence

In announcing the Ballarat Reform League charter was to be the first item added to the Victorian Heritage Register, Premier Steve Bracks claimed the document as a landmark in the history of Australia, making the comparison: "It is our Declaration of Independence. Our Magna Carta." Certainly the editor of the Ballarat Times, Henry Seekamp, writing in 1854, greeted the formation of the League with the assertion:

"This league is nothing more or less than the germ of independence. The die is cast, and fate has stamped upon the movement its indelible signature. No power on earth can now restrain the united might and headlong strides for freedom of the people of this country, and we are lost in amazement while contemplating the dazzling panorama of the Australian future. We salute the league, and tender our hopes and prayers for its prosperity. The League have undertaken a mighty task, fit only for a great people - that of changing the dynasty of the country. The League does not exactly propose, not adopt such a scheme, but know what it means, the principles it would inculcate, and that eventually it will resolve itself into an Australian Congress."

However during the Eureka trials, it was put to Seekamp that he was a "radical" who was "rousing up the people," and he may have been prone to radical nationalist hyperbole, as Carboni would later say that "Indeed, it would ill become the Times to mince in matter of such weighty importance. This League is not more or less than the germ of Australian independence."

H.R.Nicholls recalls that "some of the Irish took to rebellion as ducks to water, as did sundry foreigners who were fresh from European revolutions [of 1848]."

The reform league charter contains a hint that the movement contained those who favoured independence, stating inter alia:

"That it is not the wish of the “League” to effect an immediate separation of this Colony from the parent country, if equal laws and equal rights are dealt out to the whole free community. But that if Queen Victoria continues to act upon the ill advice of the dishonest ministers and insists upon indirectly dictating obnoxious laws for the Colony under the assumed authority of the Royal Prerogative the Reform League will endeavour to supersede such Royal Prerogative by asserting that of the People which is the most Royal of all Prerogatives, as the people are the only legitimate source of all political power."

Although the charter was framed in these terms, there have been no discoveries made, nor is there any clear and convincing evidence as to the existence of such a formal declaration of independence made at a later stage of the Eureka rebellion.

In was claimed in an article written by H.R. Nicholls in 1890, at the time of the death of Peter Lalor, that the already long deceased Alfred Black drew up a: “long, very long, very flowery and decidedly verbose ... Declaration of Independence ... This declaration was read at night-fall on the Friday, I think, to a number of persons under arms, various kinds of arms, and was cheered very loudly."

Withers says such an instrument was made at the premises of shop keeper Teddy Shannahan, and in the presence of Black, Vern, McGill, Raffaello, Curtin, Lessman, Kenworthy, and others. 47 48 Carboni wrote that McGill described claims of such a declaration on the model of the American one being made as "a gratuitous falsehood", issuing an invitation to anyone to produce "the document in question, either the original or copy of it, of course with satisfactory evidence of its being a genuine article". H.R. Nicholls had probably made pre-existing claims about a declaration, and was possibly the unnamed source in Wither's account, with Carboni saying: "I express the hope that H.R. Nicholls... will take notice of the above."

There may have been a declaration of independence drawn up by someone associated with the Eureka movement, but without official sanction, and known only to a few people in one of the factions, which had been known to act of their own initiative without any other, or even the central committee, being aware. However, the only other corroboration is also of questionable probative value. George Train, an American merchant, recalls in 1901 that McGill came to him seeking supplies of Colt revolvers, saying: "We have elected you President of our Republic." Train says he declined the opportunity to become involved, but that he did help the fugitive McGill make his escape from Victoria. It was said that starting in about 1873, Train became noted for his eccentricities, becoming known as the "champion crank of America." Whilst Train may have assisted McGill to escape, claims that McGill approached him for weapons and offered him the "presidency" of the "Five-Star Republic" are to be treated with suspicion. Historian L.G. Churchward has judged that Train's story "is most improbable" and "Apart from the singular unreliability of Train as a chronicler, a trait which was accentuated with age, it is hardly credible that McGill or any others believed anything could be done to carry on the revolt following the destruction of the Stockade. The one thing certain about McGill's actions after 3 December 1854 is that he was sheltered by Train, and that Train and others of the merchant community interceded for him." Clive Turnbull concludes that Train's version of events "is probable enough," however Turnbull then mentions Train's "strange statement that 'the miners about Maryborough' elected him as their representative in the colonial legislature." Other historians have dismissed both Train's "presidency" and "colonial legislature" claims as "unsubstantiated."

Nichols recalls that when asked what he stood for, Lalor would say "'Independence!' Plump and plain." However, according to an analysis of his record, it has been said that "if this were so, it would seem that the independence he wanted was from arbitrary rule, from encroachments by the Crown on 'British Liberty,' and that granted by access to the land, rather than the 'independence' of a republican democracy." Another historian maintains: "Lalor consistently denied that he had meant independence outside the framework of the existing government." H.R. Nicholls reiterates by saying: "I repeat, that the late leader of the rebel forces went in for independence, with a very large I; although afterwards, when other prospects opened up, the fact was denied in a faint hearted sort of a way."

Peter Lalor's father Patrick, who once represented Queen's County in the British parliament, was a supporter of Irish home rule. Older brother James Fintian considered Queen Victoria to be a "foreign tyrant," and was an influential leader in the Young Ireland Movement which advocated a wholistic approach to national revival, with certain other members making headlines after being involved in car chase and shootout with the Royal Irish Constabulary in 1848.

According to Craig, the future Eureka man was already well versed in politics and took a hard line on the Irish question, believing the people of Eire were being denied nationhood and supporting their right to continue the armed struggle against British colonial rule. Currey though speaks of a man who generally "preferred to take the world as he found it, content if he was given a fair deal and not provoked by tyranny."

Last known survivor

The last known survivor of the battle is believed to be William Edward Atherdon (1838–1936).[139][140] John Lishman Potter made the claim that he was the last which nobody questioned during his lifetime. However later research has shown that Potter was aboard the Falcon en route to Melbourne from Liverpool on 3 December 1854.[141]

Aftermath

Historian Geoffrey Blainey has commented, "Every government in the world would probably have counter-attacked in the face of the building of the stockade."[142] Hotham would receive the news that the government forces had been victorious the same day, with the Attorney-General William Stawell of others waiting outside Saint James church where he was attending a service with colonial Secretary John Forster. He immediately set about firing up the government printing press to put out placards calling for support from among the colonists.[143] Hotham proclaimed a state of martial law "even though the legal basis for it was dubious."[144]

News of the battle spread quickly to Melbourne and across the gold fields, turning a perceived government military victory in repressing a minor insurrection into a public relations disaster. On 5 December as Major General Nickle and 800 men arrive at the government camp, several thousand people attended a public meeting in Melbourne, called in support of Governor Hotham. The gathering instead condemns the police action and the meeting is hastily adjourned. When the seconder of one motion, which called for the maintenance of law and order, framed the issue as "would they support the flag of old England ... Or the new flag of the Southern Cross" the speaker was drowned out by groans from the crowd.[145][146] On 6 December 1854, a 6000 strong crowd gathers at Saint Paul's Cathedral protesting against the government's response to the Eureka riots,[147] as a group of 13 rebel prisoners are indicted for treason. In Melbourne and much of rural Victoria, and to a lesser extent the other Australian colonies, there was tremendous public outcry over the military response. Newspapers characterised it as a brutal overuse of force in a situation brought about by the actions of government officials in the first place, and public condemnation became insurmountable. Letters Patent formally appointing the members of the Royal Commission were finally signed and sealed on 7 December.[148] Eventually Hotham was able to have an auxiliary force of 1,500 special constables from Melbourne sworn in addition to others from Geelong, with his resolve that further "rioting and sedition would be speedily put down" undeterred by the immediate rebuff his policies had received from the general public. In Ballarat, only one man stepped forward and answered the call to enlist.[149] By the beginning of 1855 normalcy had returned to the streets of Ballarat with mounted patrols no longer being feature of daily life.[150]

Reverend Theophilus Taylor's observations were:

4 Dec. Quiet reigned through the day. Evening thrown into alarm by a volley of musketry fired by the sentries. The cause, it appears, was the firing into the camps by some one unknown...... 5 Dec. Martial Law proclaimed, Major-General Sir Robert Nickle arrived with a force of 1000 soldiers. The Reign of Terror commences.[116]

His note about a 'reign of terror' proved unjustified. Sir Robert Nickle was a wise, considered and even-handed military commander who calmed the tensions.[151] Miner and diarist Charles Evans recorded the effect of his conduct as follows:

Sir Robert Nichol [sic] has taken the reins of power at the Camp. Already there is a sensible and gratifying deference in its appearance. The old General went round unattended to several tents early this morning & made enquiries from the diggers relative to the cause of the outbreak. It is very probable from the humane & temperate course he is taking that he will establish himself in the goodwill of the people.[152]

On 7 December Theophilus Taylor met with Nickle and "found him to be a very affable and kind gentleman".[116]

Trials for sedition and high treason

The first trial relating to the rebellion was a charge of sedition against Henry Seekamp of the Ballarat Times. Seekamp was arrested in his newspaper office on 4 December 1854, for a series of articles that appeared in the Ballarat Times. Many of these articles were written by George Lang, the son of the prominent republican and Presbyterian Minister of Sydney, the Reverend John Dunmore Lang. He was tried and convicted of seditious libel by a Melbourne jury on 23 January 1855 and, after a series of appeals, sentenced to six months imprisonment on 23 March. He was released from prison on 28 June 1855, precisely three months early. While he was in jail, Henry Seekamp's de facto wife, Clara Seekamp took over the business, and became the first female editor of an Australian newspaper.

Of the approximately 120 'diggers' detained after the rebellion, thirteen were brought to trial. They were:[153]

- Timothy Hayes, Chairman of the Ballarat Reform League, from Ireland

- James McFie Campbell, a man of unknown African ancestry from Kingston, Jamaica

- Raffaello Carboni, an Italian and trusted lieutenant who was in charge of the European diggers as he spoke a few European languages. Carboni self-published his account of the Eureka Stockade a year after the Stockade, the only comprehensive eyewitness account

- Jacob Sorenson, a Jewish man from Scotland

- John Manning, a Ballarat Times journalist, from Ireland

- John Phelan, a friend and business partner of Peter Lalor, from Ireland

- Thomas Dignum, born in Sydney

- John Joseph, an African American from New York City or Baltimore, United States

- James Beattie, from Ireland

- William Molloy, from Ireland

- Jan Vennick, from the Netherlands

- Michael Tuohy, from Ireland

- Henry Reid, from Ireland

The first trial started on 22 February 1855, with defendants being brought before the court on charges of high treason. Joseph was one of three Americans arrested at the stockade, with the United States Consul intervening for the release of the other two Americans. The prosecution was handled by Attorney-General William Stawell representing the Crown[154] before Chief Justice William à Beckett. The jury deliberated for about half an hour before returning a verdict of "not guilty". "A sudden burst of applause arose in the court" reported The Argus, but was instantly checked by court officers. The Chief Justice condemned this as an attempt to influence the jury, as it could be construed that a jury could be encouraged to deliver a verdict that would receive such applause; he sentenced two men (identified by the Crown Solicitor as having applauded) to a week in prison for contempt.[155] Over 10,000 people had come to hear the jury's verdict. John Joseph was carried around the streets of Melbourne in a chair in triumph, according to the Ballarat newspaper The Star.

Under the auspices of Victorian Chief Justice Redmond Barry, all the other 13 accused men were rapidly acquitted to great public acclaim. The trials have on several occasions been called a farce.[156] Rede himself was quietly removed from the camps and reassigned to an insignificant position in rural Victoria.

Commission of Enquiry

On 14 December 1854, the goldfields commission sits for the first time. The first Ballarat session is held four days later at Bath's Hotel.[157] In a meeting with Hotham on 8 January 1855, the gold fields commissioners made an interim finding that the mining tax be scrapped, and two days later made a submission advising a general amnesty be granted in relation to all those persons criminally liable for their association with the Eureka rebellion.[158]

The final report of the Royal Commission into the Victorian goldfields is presented to Governor Hotham on 27 March 1855. It was scathing in its assessment of all aspects of the administration of the gold fields, and particularly the Eureka Stockade affair. Within 12 months all but one of the demands of the Ballarat Reform League is implemented. The changes included the abolition of gold licences in favour of an export duty, an annual 1 pound annual miner's right which entitled the holder to voting rights and a land deed, mining wardens replaced the gold commissioners, and a reduction in police numbers and Chinese immigration. The Legislative Council was reconstituted to provide for representation from the major goldfield settlements,[159] although property qualifications with regards to eligibility to vote in upper house elections in Victoria remained until the 1950s.

According to John Basson Humffray, the founding Secretary of the Ballarat Reform League: "The [commission] report is a most masterly and statesmanlike document, and if its wise suggestions are wisely and honestly carried out, that commission will have rendered a service to the colony... the wrongs and grievances of the digging community are clearly set forth in the Report, and practical schemes suggested for their removal."[160]

Peter Lalor

Following the battle, rebel leader, Irish Australian Peter Lalor, wrote in a statement to the colonists of Victoria, "There are two things connected with the late outbreak (Eureka) which I deeply regret. The first is, that we shouldn't have been forced to take up arms at all; and the second is, that when we were compelled to take the field in our own defence, we were unable (through want of arms, ammunition and a little organisation) to inflict on the real authors of the outbreak the punishment they so richly deserved."[161]

In July 1855, the Victorian Constitution enacted at Westminster receives royal assent, which provides for a fully elected bicameral parliament with a Legislative Assembly of 60 members and a legislative council of 30, with near universal franchise and the parliamentarians themselves subject to property qualifications. In the interim five representatives from the mining settlements had been appointed to the old legislative council including Lalor and Hummfray for the Ballarat, who were both elected unopposed in November election. Bate and Withers have both noted that people who considered Lalor a legendary folk hero were surprised that he should be more concerned accumulating styles and estates, than securing any gains arising from the Eureka rebellion.

It is a most curious thing that in 1873 Lalor continued his directorship of the Lothair gold mine at Clunes, after the Board resolved to bring in low paid Chinese workers from Ballarat and Creswick to use as strike breakers, after the employees decided to collectively withdraw their labour in an industrial dispute. Les Blake documents the episode in detail saying "So far the district has escaped the anti-Chinese riots that has occurred on other goldfields but this move proved too much. On 8 December some 500 men of the Miner's Association armed with sticks, waddies and pickhandles and led by the Clunes Brass Band, marched around the streets ... Miners the demolished a building prepared for the accommodation of the Chinese." At dawn the next day the striking European miners formed picket lines at the entrances to the mine to forcibly refuse entry to the Chinese workers, who were under police escort. The company was forced to abandon their plans as the miners began "yelling and cursing and the people of Clunes flung 'a storm of missiles' at the unfortunate troopers and coach-loads of Chinese."

Furthermore Lalor was said to have "aroused hostility among his digger constituents” by not supporting the principle of one vote, one value. He instead preferred a system based on property qualifications and plural voting, where ownership of a certain number of holdings conferred the right to cast multiple ballots, and a six-months' residency requirement. In the event when the Electoral Act of 1856 (Vic) was brought forth, the provisions were not carried forward, as universal franchise was introduced for Legislative Assembly elections. On another occasion there was 17,745 signatures from Ballarat residents on a petition against a regressive land ownership bill he supported that favoured the "squattocracy," who coming from pioneering families had acquired their prime agricultural land as a result of occupation, and who were not of a mind to give up their monopoly on the countryside, nor political representation. He was on record as having been opposed to payment to members of the Legislative Council, which had been another key demand of the Ballarat Reform League. The following November, under the new constitutional arrangements, Lalor was again elected unopposed, to the Legislative Assembly for the seat of North Grenville which he held from 1856 to 1859.Lalor stood for Ballaarat in the 1855 elections and was elected unopposed.

According to John Lynch who was fellow Eureka man, Lalor has by a certain stage been found out as wanting by a critical mass of his supporters, who had hitherto sustained his political career, who summed up the reaction to his policies in these terms:

"The semi-Chartist, revolutionary Chief, the radical reformer thus suddenly metamorphosed into a smug Tory, was surely a spectacle to make good men weep. But good men did more than weep; they decried him with vehemence in keeping with the recoil of their sentiments."

Under pressure from constituents to clarify his position, in a letter dated 1 January 1857 published in the Ballarat Star, Lalor would describe his political ideology by saying: "I would ask the gentlemen what they mean by the term 'Democracy'? Do they mean Chartism, or Communism, or Republicanism? If so, I never was, I am not now, nor do I ever intend to be a democrat. But if democracy means opposition to a tyrannical press, a tyrannical people, or a tyrannical government, then I have ever been, am still, and I ever will remain a democrat."

From thereon he never represented a Ballarat based constituency again, successfully contesting the Melbourne seat of South Grant in the Legislative Assembly in 1859, until being twice defeated at the polls in 1871, on the second occasion contesting the seat of North Melbourne. In 1874 he was once again elected as the member for South Grant, which he represented in parliament until his death in 1889.

Lalor served as chairman of committees from 1859 to 1868, before being sworn into the ministry. He was first appointed as Commissioner Trade & Customs during 1875, a posting he also held throughout 1877-1880, riding the fortunes of his parliamentary faction. He was also briefly Postmaster-General of Victoria, including from May to July 1877. Lalor would go on to seek and accept the post of Speaker which had become one of his ambitions in life, and remained as the presiding officer of the Legislative Assembly from 1880 and 1887. When his health situation forced him to step down, parliament awarded him a sum of 4,000 pounds.

Political legacy

The actual significance of Eureka upon Australia's politics is not decisive. It has been variously interpreted as a revolt of free men against imperial tyranny, of independent free enterprise against burdensome taxation, of labour against a privileged ruling class, or as an expression of republicanism. In his 1897 travel book Following the Equator, American writer Mark Twain wrote of the Eureka Rebellion:[162]

... I think it may be called the finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution—small in size; but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression. ... It is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle. It adds an honorable page to history; the people know it and are proud of it. They keep green the memory of the men who fell at the Eureka stockade, and Peter Lalor has his monument.

Raffaello Carboni, who was present at the Stockade, wrote that "amongst the foreigners ... there was no democratic feeling, but merely a spirit of resistance to the licence fee"; and he also disputes the accusations "that have branded the miners of Ballarat as disloyal to their QUEEN" (emphasis as in the original).[163] The affair continues to raise echoes in Australian politics to the present day, and from time to time one group or another calls for the existing Australian flag to be replaced by the Eureka Flag.[164][165]

Some historians believe that the prominence of the event in the public record has come about because Australian history does not include a major armed rebellion phase equivalent to the French Revolution, the English Civil War, or the American War of Independence, making the Eureka story inflated well beyond its real significance. Others, however, maintain that Eureka was a seminal event and that it marked a major change in the course of Australian history.[166]

In 1980, historian Geoffrey Blainey drew attention to the fact that many miners were temporary migrants from Britain and the United States, who did not intend to settle permanently in Australia. He wrote:

Nowadays it is common to see the noble Eureka flag and the rebellion of 1854 as the symbol of Australian independence, of freedom from foreign domination; but many saw the rebellion in 1854 as an uprising by outsiders who were exploiting the country's resources and refusing to pay their fair share of taxes. So we make history do its handsprings.[167]

In 1999, the Premier of New South Wales, Bob Carr, dismissed the Eureka Stockade as a "protest without consequence".[168] Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson made the Eureka flag a federal election campaign issue in 2004 saying "I think people have tried to make too much of the Eureka Stockade...trying to give it a credibility and standing that it probably doesn't enjoy."[169]

In 2004, the Premier of Victoria, Steve Bracks, delivered an opening address at the Eureka 150 Democracy Conference[170] stating "that Eureka was about the struggle for basic democratic rights. It was not about a riot – it was about rights."

Commemoration