Exorcism in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church authorizes the use of exorcism for those who are believed to be the victims of demonic possession. In Roman Catholicism, exorcism is a sacramental[1][2] but not a sacrament, unlike baptism or confession. Unlike a sacrament, exorcism's "integrity and efficacy do not depend ... on the rigid use of an unchanging formula or on the ordered sequence of prescribed actions. Its efficacy depends on two elements: authorization from valid and licit Church authorities, and the faith of the exorcist."[3] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: "When the Church asks publicly and authoritatively in the name of Jesus Christ that a person or object be protected against the power of the Evil One and withdrawn from his dominion, it is called exorcism."[2]

The Catholic Church revised the Rite of Exorcism in January 1999, though the traditional Rite of Exorcism in Latin is allowed as an option. The ritual assumes that possessed persons retain their free will, though the demon may hold control over their physical body, and involves prayers, blessings, and invocations with the use of the document Of Exorcisms and Certain Supplications.

Solemn exorcisms, according to the Canon law of the Church, can be exercised only by an ordained priest (or higher prelate), with the express permission of the local bishop, and only after a careful medical examination to exclude the possibility of mental illness.[4] The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) enjoined: "Superstition ought not to be confounded with religion, however much their history may be interwoven, nor magic, however white it may be, with a legitimate religious rite." Things listed in the Roman Ritual as being indicators of possible demonic possession include: speaking foreign or ancient languages of which the possessed has no prior knowledge; supernatural abilities and strength; knowledge of hidden or remote things which the possessed has no way of knowing; an aversion to anything holy; and profuse blasphemy and/or sacrilege.

The first official guidelines for exorcism were established in 1614,[5] whereas grimoire were widely known and used since the Ancient period. Those guidelines were later revised by the Vatican in 1999 as the demand for exorcisms increased. In the 15th century, Catholic exorcists were both priestly and lay, since every Christian was considered as having the power to command demons and drive them out in the name of Christ. These exorcists used the Benedictine formula "Vade retro satana" ("Step back, Satan") around this time. By the late 1960s, Roman Catholic exorcisms were seldom performed in the United States, but by the mid-1970s, popular film and literature revived interest in the ritual, with thousands claiming demonic possession. Maverick priests who belonged to fringes took advantage of the increase in demand and performed exorcisms with little or no official sanction. The exorcisms that they performed were, according to Contemporary American Religion, “clandestine, underground affairs, undertaken without the approval of the Catholic Church and without the rigorous psychological screening that the church required." In subsequent years, the Church took more aggressive action on the demon-expulsion front. The practice of exorcism without consent from the Catholic Church is what prompted the official guidelines from 1614 to be amended. The amendment established the procedure that clergy members and each individual who claims to be impacted by demonic possession must follow. This includes the rule that the potentially possessed individual must be evaluated by a medical professional before any other acts are taken. The primary reason for this action is to eliminate any suspicion of mental illness, before the next steps of the procedure are taken. Since demonic possession was extremely rare, and mental health issues are often mistaken for demonic possession, the Vatican requires that each diocese have a specially trained priest who is able to diagnose demonic possession and perform exorcisms when necessary.”[6]

When an exorcism is needed

According to the Vatican guidelines issued in 1999, “the person who claims to be possessed must be evaluated by doctors to rule out a mental or physical illness.”[7] Most reported cases do not require an exorcism because twentieth-century Catholic officials regard genuine demonic possession as an extremely rare phenomenon that is easily confounded with natural mental disturbances. As the demand for exorcisms has increased over the past few decades, the number of trained exorcists has also risen. In prior times, exorcists were kept fairly anonymous, and the performance of exorcisms remained a secret. Some exorcists attribute the rise in demand of exorcisms to the rise in drug abuse and violence, which leads to the suggestion that such things might work hand in hand. Many times a person just needs spiritual or medical help, especially if drugs or other addictions are present. The specially trained priest and medical professionals will be able to work together to address the patient, and be able to determine what type of illness the patient is suffering from. After the need of the person has been determined then the appropriate help will be met. In the circumstance of spiritual help, prayers may be offered, or the laying on of hands or a counseling session may be prescribed. The exorcist might not perform an exorcism if he does not know the person.

Signs

Signs of demonic invasion vary depending on the type of demon and its purpose, including:

- Loss or lack of appetite

- Cutting, scratching, and biting of skin

- A cold feeling in the room

- Unnatural bodily postures and change in the person's face and body

- The possessed losing control of their normal personality and entering into a frenzy or rage, and/or attacking others

- Change in the person's voice

- Supernatural physical strength not subject to the person's build or age

- Speaking in tongues

- Prediction of future events (sometimes through dreams)

- Levitation and moving of objects / things

- Expelling of objects / things

- Intense hatred/aversion and violent reaction toward all religious objects or items

- Antipathy towards entering a church, speaking Jesus' name or hearing scripture.

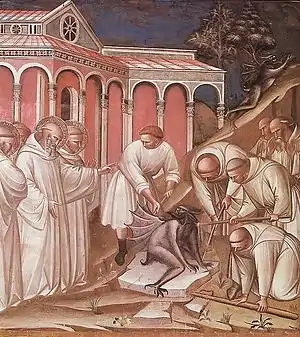

Process of the exorcism

In the process of an exorcism the person possessed may be restrained so that they do not harm themselves or any person present. The exorcist then prays and commands for the demons to retreat. The Catholic Priest recites certain prayers – the Lord's Prayer, Hail Mary, and the Athanasian Creed. Exorcists follow procedures listed in the ritual of the exorcism revised by the Vatican in 1999. Seasoned exorcists use the Rituale Romanum as a starting point, not always following the prescribed formula exactly.[8] Official practice of exorcism is governed by the Vatican document De Exorcismis et Supplicationibus Quibusdam. The Vatican offers a course on exorcism, which in 2019 for the first time was opened to members of other Christian denominations.[9] The course is called "Exorcism and Prayer of Liberation" and is offered by the Sacerdos Institute at the Regina Apostolorum Pontifical Atheneum.[10] The Gale Encyclopedia of the Unusual and Unexplained describes that an exorcism was a confrontation and not simply a prayer and once it has begun it has to finish no matter how long it takes. If the exorcist stops the rite, then the demon will pursue him which is why the process being finished is so essential.[11] After the exorcism has been finished the person possessed feels a “kind of release of guilt and feels reborn and freed of sin.”[12] Not all exorcisms are successful the first time; it could take days, weeks, or months of constant prayer and exorcisms.

Literature

On this subject, there is the book by journalist Matt Baglio[13] called The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist, first edited in 2009 and then in 2010, which inspired the film The Rite.[14][15][16]

Notable examples

- 1928 — Emma Schmidt (pseudonym Anna Ecklund) underwent a 14-day exorcism in Earling, Iowa, performed by a Catholic priest. This is the most well-documented case of demonic possession in history and a minor inspiration for The Exorcist. The priest who led this exorcism was Fr. Theophilus Riesinger.

- 1949 — Roland Doe was allegedly possessed and underwent an exorcism. The events later inspired the novel and film The Exorcist.

- 1975-1976 — Anneliese Michel was a woman from Germany who underwent 67 exorcisms, which inspired the films The Exorcism of Emily Rose and Requiem. In a conference several years later, German bishops retracted the claim that she was possessed.[17]

Saint Padre Pio, a monk and mystic, was said to have exorcised a demon by saying “long live Jesus, long live Maria (Mary)”

See also

References

- p.43 An Exorcist Tells His Story by Fr. Gabriele Amorth; Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 1999.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1673

- Martin M. (1976) Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Contemporary Americans. Harper San Francisco. Appendix one "The Roman Ritual of Exorcism" p.459 ISBN 0-06-065337-X

- THE ROMAN RITUAL Translated by PHILIP T. WELLER, S.T.D.

- Radford, Benjamin (7 March 2013). "Exorcism: Facts and Fiction About Demonic Possession". LiveScience. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Cuneo, Michael W. (Jan 1999). "Exorcism". Contemporary American Religion. 1 (New York: Macmillan Reference USA): 243.

- Goodstein, Laurie (Nov 13, 2010). "For Catholics, Interest in Exorcism is Revised". New York Times.

- The Rite, by Matt Baglio; Doubleday, New York, 2009.

- Vyse, Stuart (2019). "The New Wave of Exorcism". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 43 no. 5. Center for Inquiry. pp. 22–24.

- "Exorcism and Prayer of Liberation Course". Sacerdos Institute. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Steiger, Brad (2003). "Exorcism". The Gale Encyclopedia of the Unusual and Unexplained. 1: 204–209.

- Steiger, Brad (2003). "Demonic Invasions". The Gale Encyclopedia of the Unusual and Unexplained. 1: 179.

- "Matt Baglio". www.mattbaglio.com. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Cruz, Gilbert (2009-03-16). "Breaking News, Analysis, Politics, Blogs, News Photos, Video, Tech Reviews". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-11-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-11-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Planned Polish Exorcism Center Sparks Interest in Germany". DW. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

Further reading

- Baglio, Matt (2009). The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist. Doubleday.

- Blatty, William Peter (1972). The Exorcist. Bantam Books.

- Dickason, C. Fred (1989). Demon Possession & The Christian. Crossway Books.

- Karpel, Craig (1975). The Rite of Exorcism: The Complete Text. Berkley Books.

- Kinnaman, Gary (1994). Angels Dark and Light. Servant Publications.

- McGinn, Bernard (1994). Antichrist: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination with Evil. HarperSanFrancisco.

- MacNutt, Francis (1995). Deliverance from Evil.

- Martin, Malachi (1976). Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Living Americans.

- Nicola, John J. (1974). Diabolical Possession and Exorcism.

- Richardson, James T.; Best, Joel; Bromley, David G., eds. (1991). The Satanism Scare.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Exorcism in the Catholic Church. |

- Frequently Asked Questions About Exorcism—U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- The Catholic Prayer of Exorcism in Latin .Prof Wladimir Di Giorgio.

- What is an exorcism?