Tridentine Mass

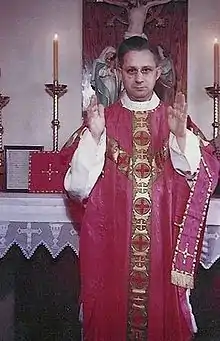

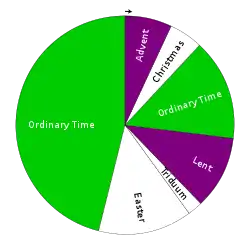

The Tridentine Mass,[1] also known as the Traditional Latin Mass (often abbreviated as TLM)[2] or Usus Antiquior, is the Roman Rite Mass of the Catholic Church which appears in typical editions of the Roman Missal published from 1570 to 1962.[3] Celebrated exclusively in Ecclesiastical Latin, it was the most widely used Eucharistic liturgy in the world from its issuance in 1570 until the introduction of the Mass of Paul VI (promulgated in 1969, with the revised Roman Missal appearing in 1970).[4]

The edition promulgated by Pope John XXIII in 1962 (the last to bear the indication ex decreto Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum) and Mass celebrated in accordance with it are described in the 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum as an authorized form of the Church's liturgy, and this form of the Tridentine Mass is often spoken of as the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.

"Tridentine" is derived from the Latin Tridentinus, "related to the city of Tridentum" (modern-day Trent, Italy), where the Council of Trent was held at the height of the Counter-Reformation. In response to a decision of that council,[5] Pope Pius V promulgated the 1570 Roman Missal, making it mandatory throughout the Latin Church, except in places and religious orders with missals from before 1370.[6] Although the Tridentine Mass is often described as the Latin Mass,[7] the post-Vatican II Mass published by Pope Paul VI and republished by Pope John Paul II,[8] which replaced it as the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, has its official text in Latin and is sometimes celebrated in that language.[9][10]

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI issued the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, accompanied by a letter to the world's bishops, authorizing use of the 1962 Tridentine Mass by all Latin Rite Catholic priests in Masses celebrated without the people. These Masses "may — observing all the norms of law — also be attended by faithful who, of their own free will, ask to be admitted".[11] Permission for competent priests to use the Tridentine Mass as parish liturgies may be given by the pastor or rector.[12]

Benedict stated that the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal is to be considered an "extraordinary form" (forma extraordinaria)[13] of the Roman Rite, of which the 1970 Mass of Paul VI is the ordinary, normal or standard form. Since that is the only authorized extraordinary form, some refer to the 1962 Tridentine Mass as "the extraordinary form" of the Mass.[14] The 1962 Tridentine Mass is sometimes referred to as the "usus antiquior" (older use) or "forma antiquior" (older form),[15] to differentiate it from the Mass of Paul VI, again in the sense of being the only one of the older forms for which authorization has been granted.

Language

In most countries, the language used for celebrating the Tridentine Mass was and is Latin. However, in Dalmatia and parts of Istria in Croatia, the liturgy was celebrated in Old Church Slavonic, and authorisation for use of this language was extended to some other Slavic regions between 1886 and 1935.[16][17]

After the publication of the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, the 1964 Instruction on implementing the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council laid down that "normally the epistle and gospel from the Mass of the day shall be read in the vernacular". Episcopal conferences were to decide, with the consent of the Holy See, what other parts, if any, of the Mass were to be celebrated in the vernacular.[18]

Outside the Roman Catholic Church, the vernacular language was introduced into the celebration of the Tridentine Mass by some Old Catholics and Anglo-Catholics with the introduction of the English Missal.

Some Western Rite Orthodox Christians, particularly in the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America, use the Tridentine Mass in the vernacular with minor alterations under the title of the "Divine Liturgy of St. Gregory".

Most Old Catholics use the Tridentine Mass, either in the vernacular or in Latin.

Terminology

The term "Tridentine Mass" applies to celebrations in accordance with the successive editions of the Roman Missal whose title attribute them to the Council of Trent (Missale Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum) and to the pope or popes who made the revision represented in the edition in question. The first of these editions is that of 1570, in which the mention of the Council of Trent is followed by a reference to Pope Pius V (Pii V Pont. Max. iussu editum).[19] The last, that of 1962, mentions the popes only generically (Missale Romanum ex decreto SS. Concilii Tridentini restitutum Summorum Pontificum cura recognitum). Editions later than that of 1962 mention the Second Vatican Council instead of the Council of Trent, as in the 2002 edition: Missale Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Oecumenici Concilii Vaticani II instauratum auctoritati Pauli Pp. VI promulgatum Ioannis Pauli Pp. II cura recognitum.[20]

Sometimes the term "Tridentine Mass" is applied restrictively to Masses in which the final 1962 edition of the Tridentine Roman Missal is used, the only edition still authorized, under certain conditions, as an extraordinary form of the Roman-Rite Mass.[21]

Some speak of this form of Mass as "the Latin Mass". This too is a restrictive use of a term whose proper sense is much wider. Even the Second Vatican Council Mass has its normative text, from which vernacular translations are made, in Latin, and, except at Masses scheduled by the ecclesiastical authorities to take place in the language of the people, it can everywhere be celebrated in Latin.[22]

A few speak of the Tridentine Mass in general or of its 1962 form as the "Gregorian Rite".[23] The term "Tridentine Rite" is also sometimes met with,[24] but Pope Benedict XVI declared it inappropriate to speak of the 1962 version and that published by later Popes as if they were two "rites". Rather, he said, it is a matter of a twofold "use" of one and the same "rite".[25]

Traditionalist Catholics, whose best-known characteristic is an attachment to the Tridentine Mass, frequently refer to it as the "Traditional Mass" or the "Traditional Latin Mass". They describe as a "codifying" of the form of the Mass the preparation of Pius V's edition of the Roman Missal, of which he said that the experts to whom he had entrusted the work collated the existing text with ancient manuscripts and writings, restored it to "the original form and rite of the holy Fathers" and further emended it.[26] To distinguish this form of Mass from the Vatican II Mass, traditionalist Catholics sometimes call it the "Mass of the Ages",[27][28][29][30][31][32] and say that it comes down to us "from the Church of the Apostles, and ultimately, indeed, from Him Who is its principal Priest and its spotless Victim".[33][34]

Pope Pius V's revision of the liturgy

At the time of the Council of Trent, the traditions preserved in printed and manuscript missals varied considerably, and standardization was sought both within individual dioceses and throughout the Latin West. Standardization was required also in order to prevent the introduction into the liturgy of Protestant ideas in the wake of the Protestant Reformation.

Pope Pius V accordingly imposed uniformity by law in 1570 with the papal bull "Quo primum", ordering use of the Roman Missal as revised by him.[26] He allowed only those rites that were at least 200 years old to survive the promulgation of his 1570 Missal. Several of the rites that remained in existence were progressively abandoned, though the Ambrosian rite survives in Milan, Italy and neighbouring areas, stretching even into Switzerland, and the Mozarabic rite remains in use to a limited extent in Toledo and Madrid, Spain. The Carmelite, Carthusian and Dominican religious orders kept their rites, but in the second half of the 20th century two of these three chose to adopt the Roman Rite. The rite of Braga, in northern Portugal, seems to have been practically abandoned: since 18 November 1971 that archdiocese authorizes its use only on an optional basis.[35]

Beginning in the late 17th century, France and neighbouring areas, such as Münster, Cologne and Trier in Germany, saw a flurry of independent missals published by bishops influenced by Jansenism and Gallicanism. This ended when Abbot Guéranger and others initiated in the 19th century a campaign to return to the Roman Missal.

Pius V's revision of the liturgy had as one of its declared aims the restoration of the Roman Missal "to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers".[26] Due to the relatively limited resources available to his scholars, this aim was in fact not realised.[36]

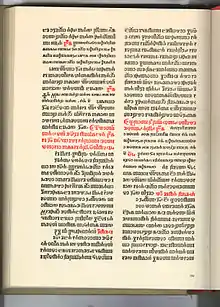

Three different printings of Pius V's Roman Missal, with minor variations, appeared in 1570, a folio and a quarto edition in Rome and a folio edition in Venice. A reproduction of what is considered to be the earliest, referred to therefore as the editio princeps, was produced in 1998.[37] In the course of the printing of the editio princeps, some corrections were made by pasting revised texts over parts of the already printed pages.[38] There were several printings again in the following year 1571, with various corrections of the text.[39]

Historical variations

In the Apostolic Constitution (papal bull) Quo primum, with which he prescribed use of his 1570 edition of the Roman Missal, Pius V decreed: "We order and enjoin that nothing must be added to Our recently published Missal, nothing omitted from it, nor anything whatsoever be changed within it." This of course did not exclude changes by a Pope, and Pope Pius V himself added to the Missal the feast of Our Lady of Victory, to celebrate the victory of Lepanto of 7 October 1571. His immediate successor, Pope Gregory XIII, changed the name of this feast to "The Most Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary" and Pope John XXIII changed it to "Our Lady of the Rosary".

Pius V's work in severely reducing the number of feasts in the Roman Calendar (see this comparison) was very soon further undone by his successors. Feasts that he had abolished, such as those of the Presentation of Mary, Saint Anne and Saint Anthony of Padua, were restored even before Clement VIII's 1604 typical edition of the Missal was issued.

In the course of the following centuries new feasts were repeatedly added and the ranks of certain feasts were raised or lowered. A comparison between Pope Pius V's Tridentine Calendar and the General Roman Calendar of 1954 shows the changes made from 1570 to 1954. Pope Pius XII made a general revision in 1955, and Pope John XXIII made further general revisions in 1960 simplifying the terminology concerning the ranking of liturgical celebrations.

While keeping on 8 December what he called the feast of "the Conception of Blessed Mary" (omitting the word "Immaculate"), Pius V suppressed the existing special Mass for the feast, directing that the Mass for the Nativity of Mary (with the word "Nativity" replaced by "Conception") be used instead. Part of that earlier Mass was revived in the Mass that Pope Pius IX ordered to be used on the feast.

Typical editions of the Roman Missal

In addition to such occasional changes, the Roman Missal was subjected to general revisions whenever a new "typical edition" (an official edition whose text was to be reproduced in printings by all publishers) was issued.

After Pius V's original Tridentine Roman Missal, the first new typical edition was promulgated in 1604 by Pope Clement VIII, who in 1592 had issued a revised edition of the Vulgate. The Bible texts in the Missal of Pope Pius V did not correspond exactly to the new Vulgate, and so Clement edited and revised Pope Pius V's Missal, making alterations both in the scriptural texts and in other matters. He abolished some prayers that the 1570 Missal obliged the priest to say on entering the church; shortened the two prayers to be said after the Confiteor; directed that the words "Haec quotiescumque feceritis, in meam memoriam facietis" ("Do this in memory of me") should not be said while displaying the chalice to the people after the consecration, but before doing so; inserted directions at several points of the Canon that the priest was to pronounce the words inaudibly; suppressed the rule that, at High Mass, the priest, even if not a bishop, was to give the final blessing with three signs of the cross; and rewrote the rubrics, introducing, for instance, the ringing of a small bell.[40]

The next typical edition was issued in 1634, when Pope Urban VIII made another general revision of the Roman Missal.[41]

There was no further typical edition until that of Pope Leo XIII in 1884.[42] It introduced only minor changes, not profound enough to merit having the papal bull of its promulgation included in the Missal, as the bulls of 1604 and 1634 were.

In 1911, with the bull Divino Afflatu,[43] Pope Pius X made significant changes in the rubrics. He died in 1914, so it fell to his successor Pope Benedict XV to issue a new typical edition incorporating his changes. This 1920 edition included a new section headed: "Additions and Changes in the Rubrics of the Missal in accordance with the Bull Divino afflatu and the Subsequent Decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites". This additional section was almost as long as the previous section on the "General Rubrics of the Missal", which continued to be printed unchanged.

Pope Pius XII radically revised the Palm Sunday and Easter Triduum liturgy, suppressed many vigils and octaves and made other alterations in the calendar (see General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII), reforms that were completed in Pope John XXIII's 1960 Code of Rubrics, which were incorporated in the final 1962 typical edition of the Tridentine Missal, replacing both Pius X's "Additions and Changes in the Rubrics of the Missal" and the earlier "General Rubrics of the Missal".

Changes made to the liturgy in 1965 and 1967 in the wake of decisions of the Second Vatican Council were not incorporated in the Roman Missal, but were reflected in the provisional vernacular translations produced when the language of the people began to be used in addition to Latin. This explains the references sometimes seen to "the 1965 Missal".

The General Roman Calendar was revised partially in 1955 and 1960 and completely in 1969 in Pope Paul VI's motu proprio Mysterii Paschalis, again reducing the number of feasts.[44]

1962 Missal

The Roman Missal issued by Pope John XXIII in 1962 differed from earlier editions in a number of ways.

- It incorporated the change made by John XXIII in 1962, when he inserted into the canon of the Mass the name of Saint Joseph, the first change for centuries in the canon of the Mass.[45]

- It incorporated major changes that Pope Pius XII made in 1955 in the liturgy of Palm Sunday and the Easter Triduum. These included:

- Abolition of the ceremonies whereby the blessing of palms on Palm Sunday resembled a Mass, with Epistle, Gospel, Preface and Sanctus; suppression of the knocking three times on the closed doors before returning to the church after the blessing and distribution of the palms; omission of the prayers at the foot of the altar and of the Last Gospel.

- On Holy Thursday the washing of feet was incorporated into the Mass instead of being an independent ceremony; if done by a bishop, 12 men, not 13, had their feet washed; the Mass itself was said in the evening instead of the morning and some of its prayers were removed or altered.

- On Good Friday, an afternoon Communion Service replaced the morning Mass of the Presanctified, at which the priest alone received the earlier-consecrated host, and drank unconsecrated wine into which a small portion of the consecrated host had been put. Elements that suggested the usual Mass were removed: incensing gifts and altar, lavabo and Orate fratres at the offertory, and the breaking of a large host. The sacred ministers began the liturgy in alb and (for celebrant and deacon) black stoles, rather than in black chasuble for the celebrant and folded chasubles for the deacon and subdeacon; they donned their vestments (without maniples) only for what was given the new name of Solemn Intercessions or Prayer of the Faithful (in which the celebrant wore a cope instead of a chasuble) and removed them for the adoration of the Cross; the sacred ministers changed to violet vestments (again, without maniples) for the newly introduced distribution of Holy Communion. The Solemn Intercessions were given new texts and "Let us pray. Let us kneel. Arise" was added at that for the Jews.

- The Easter Vigil was moved from Holy Saturday morning to the following nighttime; the use of a triple candle was abolished and other changes were made both to the initial ceremonies centred on the Paschal Candle and to other parts, such as the reduction from twelve to four of the prophecies read, and the introduction of a "renewal of baptismal promises" for the laity (notable for being the first time since the codification of the Missal of Pope Pius V that the vernacular was permitted to be used in such a manner).

- Abolition of private recitation by the priest, standing at the Epistle side of the altar, of the readings chanted or proclaimed by other ministers.

- In addition, the 1962 Missal removed from the Good Friday Prayer for the Jews the adjective perfidis, often mistakenly taken to mean "perfidious" instead of "unbelieving".[46]

- It incorporated the rubrical changes made by Pope Pius XII's 1955 decree Cum nostra, which included:

- Vigils were abolished except those of Easter, Christmas, Ascension, Pentecost, Saints Peter and Paul, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Lawrence, and the Assumption;

- all octaves were abolished except those of Easter, Christmas and Pentecost;

- no more than three collects were to be said at Low Mass and one at Solemn Mass.

- Its calendar incorporated both the changes made by Pope Pius XII in 1955 (General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII) and those introduced by Pope John XXIII himself with his 1960 Code of Rubrics (General Roman Calendar of 1960). These included:

- suppression of the "Solemnity of Saint Joseph, Spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary" (Wednesday after the second Sunday after Easter) and its replacement by the feast of "Saint Joseph the Worker" (1 May);

- removal of some duplicate feasts that appeared twice in earlier versions of the calendar, namely, the Chair of Saint Peter at Rome (18 January), the Finding of the Holy Cross (3 May), Saint John before the Latin Gate (6 May), the Apparition of Saint Michael (8 May), Saint Peter in Chains (1 August), and the Invention of the Relics of Saint Stephen (3 August);

- addition of feasts such as that of the Queenship of Mary (31 May).

- It replaced the Roman Missal's introductory sections, Rubricae generales Missalis (General Rubrics of the Missal) and Additiones et variationes in rubricis Missalis ad normam Bullae "Divino afflatu" et subsequentium S.R.C. Decretorum (Additions and alterations to the Rubrics of the Missal in line with the Bull Divino afflatu and the subsequent decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites), with the text of the General Rubrics and the General Rubrics of the Roman Missal parts of the 1960 Code of Rubrics.

Pope Benedict XVI authorized, under certain conditions, continued use of this 1962 edition of the Roman Missal as an "extraordinary form of the Roman Rite",[47] alongside the later form, introduced in 1970, which is now the normal or ordinary form.[48]

Pre-1962 forms of the Roman Rite, which some individuals and groups employ,[49] are generally not authorized for liturgical use, but in early 2018 the Ecclesia Dei Commission granted communities served by the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter an indult to use, at the discretion of the Fraternity's superior, the pre-1955 Holy Week liturgy for three years (2018, 2019, 2020).[50]

Liturgical structure

The Mass is divided into two parts, the Mass of the Catechumens and the Mass of the Faithful. Catechumens, those being instructed in the faith,[51] were once dismissed after the first half, not having yet professed the faith. Profession of faith was considered essential for participation in the Eucharistic sacrifice.[52]

This rule of the Didache is still in effect. It is only one of the three conditions (baptism, right faith and right living) for admission to receiving Holy Communion that the Catholic Church has always applied and that were already mentioned in the early 2nd century by Saint Justin Martyr: "And this food is called among us the Eucharist, of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined" (First Apology, Chapter LXVI).

Before Mass

- Asperges (Sprinkling with holy water, Psalm 51:9, 3) is an optional penitential rite that ordinarily precedes only the principal Mass on Sunday.[53] In the sacristy, a priest wearing an alb, if he is to celebrate the Mass, or surplice, if he is not the celebrant of the Mass, and vested with a stole, which is the color of the day if the priest is the celebrant of the Mass or purple if he is not the celebrant of the Mass, exorcises and blesses salt and water, then puts the blessed salt into the water by thrice sprinkling it in the form of a cross while saying once, "Commixtio salis et aquæ pariter fiat in nomine Patris, et Filii et Spiritus Sancti" (May a mixture of salt and water now be made in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit). After that, the priest, vested in a cope of the color of the day, while the choir sings an antiphon and a verse of Psalm 50/51 or 117/118, sprinkles with the holy water the altar three times, and then the clergy and the congregation. This rite, if used, precedes the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. During the Easter season, the "Asperges me..." verse is replaced by the "Vidi aquam..." verse, and "Alleluia" is added to the "Ostende nobis..." verse and to its response.

Following the Asperges, Mass begins.

Mass of the Catechumens

The first part is the Mass of the Catechumens.[54]

Prayers at the foot of the altar

The sequence of Prayers at the foot of the altar is:

- The priest, after processing in—at solemn Mass with deacon, and subdeacon, master of ceremonies and servers, and at other Masses with one or more servers—and at Low Mass placing the veiled chalice on the centre of the altar, makes the sign of the cross at the foot of the altar. At Solemn Mass, the chalice is placed beforehand on the credence table.

- Psalm 42 (Psalm 43 MT, i.e. Masoretic numbering), known by its incipit Iudica me, is recited, except in Masses of the season during Passiontide and in Requiem Masses. It is preceded and followed by an antiphon of the same psalm: "Introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui lætificat iuventutem meam" (Translation: "I shall go in to the altar of God: to God who giveth joy to my youth"),[55] is recited by the priest, alternating with the deacon and subdeacon (if present) or servers.

- Psalm 123:8 is recited:

- Priest (makes the sign of the cross): "Our help is in the name of the Lord,"

Servers: "Who made heaven and earth."

- The double form of a prayer of general confession of sins, known by its incipit Confiteor (I confess), is recited:

- Priest (while bowing low): "Confíteor Deo omnipoténti, beátæ Maríæ semper Vírgini, beáto Michaéli Archángelo, beáto Ioanni Baptístæ, sanctis Apóstolis Petro et Paulo, ómnibus Sanctis, et vobis, fratres (tibi, Pater), quia peccávi nimis cogitatióne, verbo et ópere: (while striking the breast three times) mea culpa, mea culpa, mea máxima culpa. Ídeo precor beátam Maríam semper Vírginem, beátum Michaélem Archángelum, beátum Ioánnem Baptístam, sanctos Apóstolos Petrum et Paulum, omnes Sanctos, et vos, fratres (te, Pater), oráre pro me ad Dóminum Deum nostrum."

- (Translation: I confess to almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the archangel, to blessed John the Baptist, to the holy apostles Peter and Paul, to all the saints, and to you, brethren, that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault. Therefore, I beseech blessed Mary ever Virgin, blessed Michael the archangel, blessed John the Baptist, the holy apostles Peter and Paul, all the saints and you, brethren, to pray for me to the Lord our God.)

- The servers pray for the priest: "May Almighty God have mercy on thee, forgive thee thy sins, and bring thee to life everlasting." Then it is the ministers' or servers' turn to confess sinfulness and to ask for prayers. They use the same words as those used by the priest, except that they say "you, Father," in place of "you, brethren", and the priest responds with the same prayer that the servers have used for him (but using the plural number) plus an extra prayer.

- The following verses are then said by priest and ministers (or servers):

V. Deus, tu conversus vivificabis nos.

R. Et plebs tua laetabitur in te.

V. Ostende nobis, Domine, misericordiam tuam.

R. Et salutare tuum da nobis.

V. Domine, exaudi orationem meam.

R. Et clamor meus ad te veniat.

V. Dominus vobiscum.

R. Et cum spiritu tuo.

Thou wilt turn, O God, and bring us to life: (Ps. 84:7-8)[56]

And thy people shall rejoice in thee.

Shew us, O Lord, thy mercy.

And grant us thy salvation.

O Lord, hear my prayer.

And let my cry come unto thee.

The Lord be with you.

And with thy spirit.

The priest then says, Oremus (Let us pray). After this he ascends to the altar, praying silently "Take away from us our iniquities, we beseech thee O Lord, that with pure minds we may worthily enter into the holy of holies", a reference to Exodus 26:33-34, 1 Kings 6:16, 1 Kings 8:6, 2 Chronicles 3:8, Ezekiel 41:4, and others. He places his joined hands on the edge of the altar, so that only the tips of the small fingers touch the front of it, and silently prays that, by the merits of the Saints whose relics are in the altar, and of all the Saints, God may pardon all his sins. At the words quorum relíquiæ hic sunt (whose relics are here), he spreads his hands and kisses the altar.

Priest at the altar

- Introit

- The priest again makes the sign of the Cross while he begins to read the Introit, which is usually taken from a Psalm. Exceptions occur: e.g. the Introit for Easter Sunday is adapted from Wis 10:20-21, and the antiphon in Masses of the Blessed Virgin Mary was from the poet Sedulius. This evolved from the practice of singing a full Psalm, interspersed with the antiphon, during the entrance of the clergy, before the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar were added to the Mass in medieval times. This is indicated by the very name of "Introit".

- Kyrie

- This part of Mass is a linguistic marker of the origins of the Roman liturgy in Greek. "Kyrie, eleison; Christe, eleison; Kyrie, eleison." means "Lord, have mercy; Christ have mercy;..." Each phrase is said (or sung) three times.

- Gloria in excelsis Deo

- The first line of the Gloria[58] is taken from Lk 2:14. The Gloria is omitted during the penitential liturgical seasons of Advent, Septuagesima, Lent, and Passiontide, in which violet vestments are worn, but is used on feasts falling during such seasons, as well as on Holy Thursday. It is always omitted for a Requiem Mass.

- The Collect

- The priest turns toward the people and says, "Dominus vobiscum." The servers respond: "Et cum spiritu tuo." ("The Lord be with you." "And with thy spirit"). The Collect follows, a prayer not drawn directly from Scripture. It tends to reflect the season.

Instruction

- The priest reads the Epistle, primarily an extract from the letters of St. Paul to various churches. In his motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, Pope Benedict XVI has permitted this to be read in the vernacular language when Mass is celebrated with the people.[59]

- Between the Epistle and the Gospel two (rarely three) choir responses are sung or said. Usually these are a Gradual followed by an Alleluia; but between Septuagesima Sunday and Holy Saturday, or in a Requiem Mass or other penitential Mass the Alleluia is replaced by a Tract, and between Easter Sunday and Pentecost the Gradual is replaced by a second Alleluia. On a few exceptional occasions (most notably Easter, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, and in a Requiem Mass), a Sequence follows the Alleluia or Tract.

- The Gradual is partly composed of a portion of a Psalm.

- The Gospel reading, an extract from one of the four Gospels

- The Homily

- The rite of Mass as revised by Pope Pius V (the Tridentine Mass) does not consider a sermon obligatory and speaks of it instead as merely optional: it presumes that the Creed, if it is to be said, will follow the Gospel immediately, but adds: "If, however, someone is to preach, the Homilist, after the Gospel has been finished, preaches, and when the sermon or moral address has been completed, the Credo is said, or if it is not to be said, the Offertory is sung."[60] By contrast the Roman Missal as revised by Pope Paul VI declares that the homily may not be omitted without a grave reason from Mass celebrated with the people attending on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation and that it is recommended on other days.[61]

- The Creed

- The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, professing faith in God the Father, in God the Son, in God the Holy Spirit, and in the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church. At the mention of the Incarnation, the celebrant and the congregation genuflect.

Mass of the Faithful

The second part is the Mass of the Faithful.[62]

Offertory

- Offertory Verse

- After greeting the people once more ("Dominus vobiscum/Et cum spiritu tuo") and giving the invitation to pray (Oremus), the priest enters upon the Mass of the Faithful, from which the non-baptized were once excluded. He reads the Offertory Verse, a short quotation from Holy Scripture which varies with the Mass of each day, with hands joined.

- Offering of Bread and Wine

- The priest offers the host, holding it on the paten at breast level and praying that, although he is unworthy, God may accept "this spotless host (or victim, the basic meaning of hostia in Latin) for his own innumerable sins, offences and neglects, for all those present, and for all faithful Christians living and dead, that it may avail unto salvation of himself and those mentioned. He then mixes a few drops of water with the wine, which will later become the Blood of Jesus, and holding the chalice so that the lip of the chalice is about the height of his lips, offers "the chalice of salvation", asking that it may "ascend with a sweet fragrance." He then prays a prayer of contrition adapted from Dan 3:39-40.

- Incensing of the offerings and of the faithful

- At a High Mass, the priest blesses the incense, then incenses the bread and wine. Among the prayers the priest says is Psalm 141:2-4: "Let my prayer, O Lord, be directed as incense in Thy sight;...", which is prayed as he incenses the altar. The priest then gives the thurible to the deacon, who incenses the priest, then the other ministers and the congregation.

- Washing the hands

- Prayer to the Most Holy Trinity

- This prayer asks that the Divine Trinity may receive the oblation being made in remembrance of the passion, resurrection and ascension of Jesus and in honour of blessed Mary ever Virgin and the other saints, "that it may avail to their honour and our salvation: and that they may vouchsafe to intercede for us in heaven..."

- Orate fratres, Suscipiat and Secret; Amen concludes Offertory

- Here the priest turns to the congregation and says the first two words, "Orate, fratres," in an elevated tone and then turns around while finishing the exhortation in the secret tone. "Pray, Brethren, that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the Father almighty."

- The altar servers respond with the Suscipiat to which the priest secretly responds, "Amen.": Suscipiat Dominus sacrificium de manibus tuis, ad laudem et gloriam nominis sui, ad utilitatem quoque nostram, totiusque ecclesiæ suae sanctæ. A translation in the English is: "May the Lord accept this sacrifice at your hands, to the praise and glory of His name, for our good and the good of all His Holy Church."

- The Priest then says the day's Secret inaudibly, and concludes it with Per omnia sæcula sæculorum aloud.

- The altar servers and (in dialogue Mass) the congregation respond: "Amen."

Consecration

- Preface of the Canon

- "The Roman Canon dates in essentials from before St. Gregory the Great, who died in 604, and who is credited with adding a phrase to it.[63] (See History of the Roman Canon.) It contains the main elements found in almost all rites, but in an unusual arrangement and it is unclear which part should be considered to be the Epiclesis.

- Dominus vobiscum. Et cum spiritu tuo. Sursum corda. Habemus ad Dominum. Gratias agimus Domino Deo nostro. Dignum et iustum est. The first part can be seen above at the Collect; the rest means: Lift up your hearts. We lift them up to the Lord. Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. It is right and just.

- Next a preface is prayed, indicating specific reasons for giving thanks to God. This leads to the Sanctus.[64]

- Canon or rule of consecration[65]

- Intercession (corresponding to the reading of the diptychs in the Byzantine Rite—a diptych is a two-leaf painting, carving or writing tablet.[66])

- Here the priest prays for the living, that God may guard, unite and govern the Church together with the Pope and "all those who, holding to the truth, hand on the catholic and apostolic faith". Then specific living people are mentioned, and the congregation in the church. Next, Mary ever Virgin, Saint Joseph, the Apostles, and some Popes and other Martyrs are mentioned by name, as well as a generic "and all your Saints", in communion with whom prayer is offered.

- Prayers preparatory to the consecration

- A prayer that God may graciously accept the offering and "command that we be delivered from eternal damnation and counted among the flock of those you have chosen".

- Consecration (transubstantiation) and major elevation

- The passage Lk 22:19-20 is key in this section. In Summa Theologiae III 78 3 Thomas Aquinas addresses the interspersed phrase, "the mystery of faith". On this phrase, see Mysterium fidei.

- Oblation of the victim to God

- An oblation is an offering;[67] the pure, holy, spotless victim is now offered, with a prayer that God may accept the offering and command his holy angel to carry the offering to God's altar on high, so that those who receive the Body and Blood of Christ "may be filled with every grace and heavenly blessing".

- Remembrance of the Dead

- The priest now prays for the dead ("those who have gone before us with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace") and asks that they be granted a place of refreshment, light and peace. This is followed by a prayer that we be granted fellowship with the Saints. John the Baptist and fourteen martyrs, seven men and seven women, are mentioned by name.

- End of the Canon and doxology with minor elevation

- The concluding doxology is: Per ipsum, et cum ipso, et in ipso, est tibi Deo Patri omnipotenti, in unitate Spiritus Sancti, ("Through him, and with him, and in him, O God, there is to you, almighty Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit," − spoken silently while making five signs of the cross with the host) omnis honor, et gloria. ("all glory and honour." − still silently while briefly raising host and chalice a little together). This is followed by replacing the host on the corporal and the pall on the chalice and genuflecting. After this the priest sings or says aloud: Per omnia sæcula sæculorum" ("For ever and ever." The response "Amen" symbolically ratifies the Canon prayer.

- Intercession (corresponding to the reading of the diptychs in the Byzantine Rite—a diptych is a two-leaf painting, carving or writing tablet.[66])

Elevation candle

Until 1960, the Tridentine form of the Roman Missal laid down that a candle should be placed at the Epistle side of the altar and that it should be lit at the showing of the consecrated sacrament to the people.[68] In practice, except in monasteries and on special occasions, this had fallen out of use long before Pope John XXIII replaced the section on the general rubrics of the Roman Missal with his Code of Rubrics, which no longer mentioned this custom. On this, see Elevation candle.

Communion

- The Lord's Prayer and Libera nos[69]

- The "Libera nos" is an extension of the Lord's Prayer developing the line "sed libera nos a malo" ("but deliver us from evil"). The priest prays that we may be delivered from all evils and that the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, together with the apostles and saints, may intercede to obtain for us peace in our day.

- Fraction of the Host

- During the preceding prayer, the priest breaks the consecrated Host into three parts, and after concluding the prayer drops the smallest part into the Chalice while praying that this commingling and consecration of the Body and Blood of Christ may "be to us who receive it effectual to life everlasting."

- "Agnus Dei" means "Lamb of God". The priest then prays: "Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy on us." He repeats this, and then adds: "Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, grant us peace." The Mass of the Last Supper on Holy Thursday has "have mercy on us" all three times. In Requiem Masses, the petitions are "grant them rest" (twice), followed by "grant them eternal rest."

- The Pax

- The priest asks Christ to look not at the priest's sins but at the faith of Christ's Church, and prays for peace and unity within the Church. Then, if a High Mass is being celebrated, he gives the sign of peace to the deacon, saying: "Peace be with you."

- Prayers preparatory to the Communion

- In the first of these two prayers for himself, the priests asks that by Holy Communion he may be freed from all his iniquities and evils, be made to adhere to the commandments of Jesus and never be separated from him. In the second he asks: "Let not the partaking of Thy Body, O Lord Jesus Christ...turn to my judgment and condemnation: but through Thy goodness may it be unto me a safeguard...."

- Receiving of the Body and Blood of our Lord

- The priest quietly says several prayers here, before receiving Communion. The first is said in a low voice while taking up the Host onto the paten. The second of them, spoken three times in a slightly audible voice,[70] while the priest holds the Host in his left hand and strikes his breast with his right, is based on Matthew 8:8: "Lord, I am not worthy...." Then, after having reverently consumed the Host, he takes up the chalice while in a low voice reciting Psalm 116:12–13: "What shall I render to the Lord, for all the things he hath rendered unto me? I will take the chalice of salvation; and I will call upon the name of the Lord." immediately adding Psalm 18:3: "Praising I will call upon the Lord: and I shall be saved from my enemies."

- If the priest is to give Communion to others, he holds up a small host and says aloud: "Behold the Lamb of God ...", and three times: "Lord, I am not worthy ...". He then gives Communion, first making with the host the sign of the cross over each communicant, while saying: "May the Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ preserve your soul for eternal life. Amen."[71]

Conclusion

- Prayers during the Ablutions

- The prayers now focus on what has been received, that "we may receive with a pure mind", "that no stain of sin may remain in me, whom these pure and holy sacraments have refreshed."

- Communion Antiphon and Postcommunion

- The communion antiphon is normally a portion of a Psalm. The Postcommunion Prayer is akin to the Collect in being an appropriate prayer not directly drawn from Scripture.

- Ite Missa est; Blessing

- "Go, it is the dismissal." The word "Mass" derives from this phrase.

- After saying a silent prayer for himself, the priest then gives the people his blessing.

- Prior to the revisions of Pope Pius XII and Pope John XXIII, the Ite Missa est was replaced with Benedicamus Domino ("Let us bless the Lord") on days in which the Gloria was not said and the rubrics required the priest to wear violet vestments (i.e., Masses of the season during Advent, Septuagesima, Lent and Passiontide; vigils; certain votive Masses). In the 1962 Missal, Benedicamus Domino is said only when the Mass is followed by another liturgical action, such as the Eucharistic Processions on Holy Thursday and Corpus Christi.

- In Requiem Masses, the Ite Missa est is replaced with Requiescant in pace, with the response being "Amen" instead of Deo gratias.

- The Last Gospel

- The priest then reads the Last Gospel, the beginning of the Gospel of John, John 1:1–14, which recounts the Incarnation of the Son of God. On certain occasions, as for instance at the Day Mass on Christmas Day, another Gospel passage was read instead because that Gospel is read as the Gospel of the Mass, but Pope John XXIII's revision of the rubrics decreed that on those and on other occasions the Last Gospel should simply be omitted.

Prayers of the priest before and after Mass

The Tridentine Missal includes prayers for the priest to say before and after Mass.

In later editions of the Roman Missal, including that of 1962, the introductory heading of these prayers indicates that they are to be recited pro opportunitate (as circumstances allow),[72] which in practice means that they are merely optional and may be omitted. The original Tridentine Missal presents most of the prayers as obligatory, indicating as optional only a very long prayer attributed to Saint Ambrose (which later editions divide into seven sections, each to be recited on only one day of the week) and two other prayers attributed to Saint Ambrose and Saint Thomas Aquinas respectively.[73]

In addition to these three prayers, the original Tridentine Missal proposes for the priest to recite before he celebrates Mass the whole of Psalms 83–85, 115, 129 (the numbering is that of the Septuagint and Vulgate), and a series of collect-style prayers. Later editions add, after the three that in the original Missal are only optional, prayers to the Blessed Virgin, Saint Joseph, all the angels and saints, and the saint whose Mass is to be celebrated, but, as has been said, treats as optional all the prayers before Mass, even those originally given as obligatory.[74]

The original Tridentine Missal proposes for recitation by the priest after Mass three prayers, including the Adoro te devote. Later editions place before these three the Canticle of the Three Youths (Dan)[75] with three collects, and follow them with the Anima Christi and seven more prayers, treating as optional even the three prescribed in the original Tridentine Missal.[76]

Leonine Prayers

From 1884 to 1965, the Holy See prescribed the recitation after Low Mass of certain prayers, originally for the solution of the Roman Question and, after this problem was solved by the Lateran Treaty, "to permit tranquillity and freedom to profess the faith to be restored to the afflicted people of Russia".[77]

These prayers are known as the Leonine Prayers because it was Pope Leo XIII who on 6 January 1884 ordered their recitation throughout the world. In what had been the Papal States, they were already in use since 1859.

The prayers comprised three Ave Marias, one Salve Regina followed by a versicle and response, and a collect prayer that, from 1886 on, asked for the conversion of sinners and "the freedom and exaltation of Holy Mother the Church", and, again from 1886 on, a prayer to Saint Michael. In 1904, Pope Pius X added a thrice-repeated "Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, have mercy on us."

In 1964, with effect from 7 March 1965, the Holy See ended the obligation to recite the Leonine Prayers after Low Mass.[78] However, the Leonine Prayers are sometimes still recited after present-day celebrations of Tridentine Mass, although they are not included even in the 1962 edition of the Tridentine Missal.

Participation by the people

The participation of the congregation at the Tridentine Mass is interior, involving eye and heart, and exterior by mouth.[79]

Except in the Dialogue Mass form, which arose about 1910 and led to a more active exterior participation of the congregation, the people present at the Tridentine Mass do not recite out loud the prayers of the Mass. Only the server or servers join with the priest in reciting the prayers at the foot of the altar (which include the Confiteor) and in speaking the other responses.[80] Most of the prayers that the priest says are spoken inaudibly, including almost all the Mass of the Faithful: the offertory prayers, the Canon of the Mass (except for the preface and the final doxology), and (apart from the Agnus Dei) those between the Lord's Prayer and the postcommunion.

At a Solemn Mass or Missa Cantata, a choir sings the servers' responses, except for the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. The choir sings the Introit, the Kyrie, the Gloria, the Gradual, the Tract or Alleluia, the Credo, the Offertory and Communion antiphons, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei. Of these, only the five that form part of the Ordinary of the Mass are usually sung at a Missa Cantata. In addition to the Gregorian Chant music for these, polyphonic compositions exist, some quite elaborate. The priest largely says quietly the words of the chants and then recites other prayers while the choir continues the chant.

Different levels of celebration

There are various forms of celebration of the Tridentine Mass:

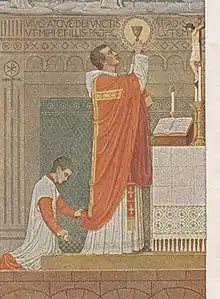

- Pontifical High Mass: celebrated by a bishop accompanied by an assisting priest, deacon, subdeacon, thurifer, acolytes and other ministers, under the guidance of a priest acting as Master of Ceremonies. Most often the specific parts assigned to deacon and subdeacon are performed by priests. The parts that are said aloud are all chanted, except that the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar, which before the reform of Pope Pius V were said in the sacristy, are said quietly by the bishop with the deacon and the subdeacon, while the choir sings the Introit. The main difference between a pontifical and an ordinary High Mass is that the bishop remains at his cathedra almost all the time until the offertory.

- Solemn or High Mass (Latin: Missa solemnis): offered by a priest accompanied by a deacon and subdeacon and the other ministers mentioned above.

- Missa Cantata (Latin for "sung mass"): celebrated by a priest without deacon and subdeacon, and thus a form of Low Mass, but with some parts (the three variable prayers, the Scripture readings, Preface, Pater Noster, and Ite Missa Est) sung by the priest, and other parts (Introit, Kyrie, Gloria, Gradual, Tract or Alleluia, Credo, Offertory Antiphon, Sanctus and Benedictus, Agnus Dei, and Communion Antiphon) sung by the choir. Incense may be used exactly as at a Solemn Mass with the exception of incensing the celebrant after the Gospel which is not done.

- Low Mass: the priest sings no part of the Mass, though in some places a choir or the congregation sings, during the Mass, hymns not always directly related to the Mass.

In its article "The Liturgy of the Mass", the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia describes how, when concelebration ceased to be practised in Western Europe, Low Mass became distinguished from High Mass:[81]

- The separate celebrations then involved the building of many altars in one church and the reduction of the ritual to the simplest possible form. The deacon and subdeacon were in this case dispensed with; the celebrant took their part as well as his own. One server took the part of the choir and of all the other ministers, everything was said instead of being sung, the incense and kiss of peace were omitted. So we have the well-known rite of low Mass (missa privata). This then reacted on high Mass (missa solemnis), so that at high Mass too the celebrant himself recites everything, even though it be sung by the deacon, subdeacon, or choir.

On the origin of the "Missa Cantata", the same source gives the following information:

- ... high Mass is the norm; it is only in the complete rite with deacon and subdeacon that the ceremonies can be understood. Thus, the rubrics of the Ordinary of the Mass always suppose that the Mass is high. Low Mass, said by a priest alone with one server, is a shortened and simplified form of the same thing. Its ritual can be explained only by a reference to high Mass. For instance, the celebrant goes over to the north side of the altar to read the Gospel, because that is the side to which the deacon goes in procession at high Mass; he turns round always by the right, because at high Mass he should not turn his back to the deacon and so on. A sung Mass (missa Cantata) is a modern compromise. It is really a low Mass, since the essence of high Mass is not the music but the deacon and subdeacon. Only in churches which have no ordained person except one priest, and in which high Mass is thus impossible, is it allowed to celebrate the Mass (on Sundays and feasts) with most of the adornment borrowed from high Mass, with singing and (generally) with incense.

Revision of the Roman Missal

Pius XII began in earnest the work of revising the Roman Missal with a thorough revision of the rites of Holy Week, which, after an experimental period beginning in 1951, was made obligatory in 1955. The Mass that used to be said on Holy Thursday morning was moved to the evening, necessitating a change in the rule that previously had required fasting from midnight. The Good Friday service was moved to the afternoon, Holy Communion was no longer reserved for the priest alone (as before, hosts consecrated at the Holy Thursday Mass were used) and the priest no longer received part of the host in unconsecrated wine. The Easter Vigil service that used to be held in morning of Holy Saturday[82] was moved to the night that leads to Easter Sunday and many changes were made to the content.

In 1960, Pope John XXIII (1958–1963) ordered the suppression of the word "perfidis" ("unbelieving" i.e. not believing in Jesus), applied to the Jews, in the rites for Good Friday. He revised the rubrics to the Order of Mass and the Breviary. Two years later, in 1962, he made some more minor modifications on the occasion of publishing a new typical edition of the Roman Missal. This is the edition authorized for use by virtue of the Quattuor abhinc annos indult (see below, under Present status of the Tridentine Mass). Among the other changes he made and that were included in the 1962 Missal were: adding St. Joseph's name to the Roman Canon; eliminating the second Confiteor before Communion; suppressing 10 feasts, such as St. Peter's Chair in Rome (or, more accurately, combining both feasts of St Peter's Chair into one, as they originally had been); incorporating the abolition of 4 festal octaves and 9 vigils of feasts and other changes made by Pope Pius XII; and modifying rubrics especially for Solemn High Masses.[83] Among the names that disappeared from the Roman Missal was that of St Philomena: her liturgical celebration had never been admitted to the General Roman Calendar, but from 1920 it had been included (with an indication that the Mass was to be taken entirely from the common) in the section headed "Masses for some places", i.e. only those places for which it had been specially authorized; but her name had already in 1961 been ordered to be removed from all liturgical calendars.

On 4 December 1963, the Second Vatican Council decreed in Chapter II of its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium:[84]

"[T]he rite of the Mass is to be revised ... the rites are to be simplified, due care being taken to preserve their substance. Parts which with the passage of time came to be duplicated, or were added with little advantage, are to be omitted. Other parts which suffered loss through accidents of history are to be restored to the vigor they had in the days of the holy Fathers, as may seem useful or necessary. The treasures of the Bible are to be opened up more lavishly so that a richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God’s word ... A suitable place may be allotted to the vernacular in Masses which are celebrated with the people ... communion under both kinds may be granted when the bishops think fit...as, for instance, to the newly ordained in the Mass of their sacred ordination, to the newly professed in the Mass of their religious profession, and to the newly baptized in the Mass which follows their baptism..."

The instruction Inter Oecumenici of 26 September 1964 initiated the application to the Mass of the decisions that the Council had taken less than a year before. Permission was given for use, only in Mass celebrated with the people, of the vernacular language, especially in the Biblical readings and the reintroduced Prayers of the Faithful, but, "until the whole of the Ordinary of the Mass has been revised," in the chants (Kyrie, Gloria, Creed, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and the entrance, offertory and communion antiphons) and in the parts that involved dialogue with the people, and in the Our Father, which the people could now recite entirely together with the priest. Most Episcopal Conferences quickly approved interim vernacular translations, generally different from country to country, and, after having them confirmed by the Holy See, published them in 1965. Other changes included the omission of Psalm 43 (42) at the start of Mass and the Last Gospel at the end, both of which Pope Pius V had first inserted into the Missal (having previously been private prayers said by the priest in the sacristy), and the Leonine Prayers of Pope Leo XIII. The Canon of the Mass, which continued to be recited silently, was kept in Latin.

Three years later, the instruction Tres abhinc annos[85] of 4 May 1967 gave permission for use of the vernacular even in the Canon of the Mass, and allowed it to be said audibly and even, in part, to be chanted; the vernacular could be used even at Mass celebrated without the people being present. Use of the maniple was made optional, and at three ceremonies at which the cope was previously the obligatory vestment the chasuble could be used instead.

Pope Paul VI continued implementation of the Council's directives, ordering with Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum[86] of Holy Thursday, 3 April 1969, publication of a new official edition of the Roman Missal, which appeared (in Latin) in 1970.

Opposition to the latest revisions of the liturgy

Some Traditionalist Catholics reject to a greater or lesser extent the changes made since 1950. None advocate returning to the original (1570) form of the liturgy, though some may perhaps wish a re-establishment of its form before Pius X's revision of the rubrics in 1911. Some do refuse to accept the 1955 changes in the liturgy of Palm Sunday and the Easter Triduum and in the liturgical calendar (see General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII), and instead use the General Roman Calendar as in 1954. Others accept the 1955 changes by Pius XII, but not those of Pope John XXIII. Others again, in accordance with the authorization granted by Pope Benedict XVI in Summorum Pontificum, use the Missal and calendar as it was in 1962.

Some of them argue that, unlike earlier reforms, the revision of 1969-1970 which replaced the Tridentine Mass with the Mass of Pope Paul VI represented a major break with the past. They consider that the content of the revised liturgy is, in Catholic terms, seriously deficient and defective; some hold that it is displeasing to God, and that no Catholic should attend it.[87]

When a preliminary text of two of the sections of the revised Missal was published in 1969, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre gathered a group of twelve theologians, who, under his direction,[88] wrote a study of the text. They stated that it "represents, both as a whole and in its details, a striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass as it was formulated in Session 22 of the Council of Trent".[89] Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, a former Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, supported this study with a letter of 25 September 1969 to Pope Paul VI. Cardinal Antonio Bacci signed the same letter. The critical study became known as "the Ottaviani Intervention".[90] Cardinal Ottaviani subsequently stated in writing that he had not intended his letter to be made public, and that Pope Paul VI's doctrinal exposition, on 19 November[91] and 26 November 1969,[92] of the revised liturgy in its definitive form meant that "no one can be genuinely scandalised any more".[93] Jean Madiran, a critic of Vatican II[94] and founder-editor of the French journal Itinéraires, claimed that this letter was fraudulently presented to the elderly and already blind cardinal for his signature by his secretary, Monsignor (and future Cardinal) Gilberto Agustoni, and that Agustoni resigned shortly afterwards.[95] This allegation remains unproven, and Madiran himself was not an eyewitness of the alleged deception.[96]

In October 1967, a meeting of the Synod of Bishops had already given its opinion on a still earlier draft. Of the 187 members, 78 approved it as it stood, 62 approved it but suggested various modifications, 4 abstained, and 47 voted against.[97]

From the 1960s onwards, Western countries have experienced a drop in Mass attendance (in the United States, from 75% of Catholics attending in 1958 to 25% attending by 2002). These same countries saw a decline in seminary enrollments and in the number of priests (in the United States, from 1,575 ordinations in 1954 to 450 in 2002), and a general erosion of belief in the doctrines of the Catholic faith. Opponents of the revision of the Mass liturgy argue, citing opinion poll evidence in their support, that the revision contributed to this decline.[98] Others, pointing, among other considerations, to the fact that, globally, there are more priests and seminarians now than in previous years (in 1970, there were 72,991 major seminarians worldwide, in 2002, there were 113,199, an increase of 55%, at a time, however, when there was an increase of global population of 64%),[99] suggest that the apparent decline of Catholic practice in the West is due to the general influence of secularism and liberalism on Western societies rather than to developments within the Church.

Attitudes of Popes since the Second Vatican Council

Pope Paul VI

Following the introduction of the Mass of Paul VI in 1969-1970, the Holy See granted a significant number of permissions for the use of the former liturgy. For example, elderly priests were not required to switch to celebrating the new form. In England and Wales, occasional celebrations of the Tridentine Mass were allowed in virtue of what became known as the "Agatha Christie indult". However, there was no general worldwide legal framework allowing for the celebration of the rite. Following the rise of the Traditionalist Catholic movement in the 1970s, Pope Paul VI reportedly declined to liberalise its use further on the grounds that it had become a politically charged symbol associated with opposition to his policies.[100]

Pope John Paul II

In 1984, the Holy See sent a letter known as Quattuor abhinc annos to the presidents of the world's Episcopal Conferences. This document empowered diocesan bishops to authorise, on certain conditions, celebrations of the Tridentine Mass for priests and laypeople who requested them.[101] In 1988, following the excommunication of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and four bishops that he had consecrated, the Pope issued a further document, a motu proprio known as Ecclesia Dei,[102] which stated that "respect must everywhere be shown for the feelings of all those who are attached to the Latin liturgical tradition". The Pope urged bishops to give "a wide and generous application" to the provisions of Quattuor abhinc annos, and established the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei to oversee relations between Rome and Traditionalist Catholics.

The Holy See itself granted authorisation to use the Tridentine Mass to a significant number of priests and priestly societies, such as the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, and the Personal Apostolic Administration of Saint John Mary Vianney. Some diocesan bishops, however, declined to authorise celebrations within their dioceses, or did so only to a limited extent. In some cases, the difficulty was that those seeking the permission were hostile to the church authorities. Other refusals of permission were alleged to have stemmed from certain bishops' disapproval in principle of celebrations of the Tridentine liturgy.

Pope Benedict XVI

As a cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger was regarded as having a particular interest in the liturgy, and as being favourable towards the pre-Vatican II Mass.[103] He criticized the erratic way in which, contrary to official policy, many priests celebrated the post-Vatican II form.[104]

In September 2006, the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei established the Institute of the Good Shepherd, made up of former members of the Society of St. Pius X, in Bordeaux, France, with permission to use the Tridentine liturgy.[105] This step was met with some discontent from French clergy, and thirty priests wrote an open letter to the Pope.[106] Consistently with its previous policy, the Society of St Pius X rejected the move.[107]

Following repeated rumours that the use of the Tridentine Mass would be liberalised, the Pope issued a motu proprio called Summorum Pontificum on 7 July 2007,[108] together with an accompanying letter to the world's Bishops.[109] The Pope declared that "the Roman Missal promulgated by Paul VI is the ordinary expression of the lex orandi (law of prayer) of the Catholic Church of the Latin rite. Nevertheless, the Roman Missal promulgated by St. Pius V and reissued by St. John XXIII is to be considered as an extraordinary expression of that same 'Lex orandi'".[110] He further stated that "the 1962 Missal ... was never juridically abrogated".[111] He replaced with new rules those of Quattuor Abhinc Annos on use of the older form: essentially, authorization for using the 1962 form for parish Masses and those celebrated on public occasions such as a wedding is devolved from the local bishop to the priest in charge of a church, and any priest of the Latin Rite may use the 1962 Roman Missal in "Masses celebrated without the people", a term that does not exclude attendance by other worshippers, lay or clergy.[112] While requests by groups of Catholics wishing to use the Tridentine liturgy in parish Masses are to be dealt with by the parish priest (or the rector of the church) rather than, as before, by the local bishop, the Pope and Cardinal Darío Castrillón stated that the bishops' authority is not thereby undermined.[113]

Present regulations

The regulations set out in Summorum Pontificum provide that:

- In Masses celebrated "without the people", every Latin Rite priest may use either the 1962 Roman Missal or that of Paul VI except during the Easter Triduum (when Masses without participation by the people are no longer allowed). Celebrations of Mass in this form (formerly referred to as "private Masses") may, as before, be attended by laypeople who ask to be admitted.[114]

- In parish Masses, where there is a stable group of laypeople who adhere to the earlier liturgical tradition, the parish priest should willingly accept their requests to be allowed to celebrate the Mass according to the 1962 Missal, and should ensure that their welfare harmonises with the ordinary pastoral care of the parish, under the guidance of the bishop in accordance with canon 392 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, avoiding discord and favouring the unity of the Church.

- Mass may be celebrated using the 1962 Missal on working days, while on Sundays and feast days one such celebration may be held.

- For priests and laypeople who request it, the parish priest should allow celebrations of the 1962 form on special occasions such as weddings, funerals, and pilgrimages.

- Communities belonging to institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life which wish to use the 1962 Missal for conventual or "community" celebration in their oratories may do so.

With letter 13/2007 of 20 January 2010 the Pontifical Council Ecclesia Dei responded positively to a question whether a parish priest (pastor) or another priest may on his own initiative publicly celebrate the extraordinary form, along with the customary regular use of the new form, "so that the faithful, both young and old, can familiarize themselves with the old rites and benefit from their perceptible beauty and transcendence". Although the Council accompanied this response with the observation that a stable group of the faithful attached to the older form has a right to assist at Mass in the extraordinary form, a website that published the response interpreted it as not requiring the existence of such a stable group.[115]

Present practice

The publication of Summorum Pontificum has led to an increase in the number of regularly scheduled public Tridentine Masses. On 14 June 2008 Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos told a London press conference that Pope Benedict wants every parish to offer both the old and the new forms for Sunday Mass.[116]

The cardinal said that the Vatican was preparing to instruct seminaries to teach all students the Tridentine form of the Roman Rite. The complexity of the rubrics makes it difficult for priests accustomed to the simpler modern form to celebrate the Tridentine form properly, and it is unclear how many have the required knowledge.

Some Traditionalist Catholic priests and organisations, holding that no official permission is required to use any form of the Tridentine Mass, celebrate it without regularizing their situation,[117] and sometimes using editions of the Roman Missal earlier than the 1962 edition approved in Summorum Pontificum.

In order to provide for priests who celebrate the Tridentine Mass, publishers have issued facsimiles or reprintings of old missals. There were two new printings of the 1962 Tridentine Missal in 2004: one, with the imprimatur of Bishop Fabian Bruskewitz of Lincoln, Nebraska, by Baronius Press in association with the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter; the other by the Society of St. Pius X's publishing house, Angelus Press. In 2008 PCP Books also produced a facsimile of the 1962 altar missal.

Reproductions of texts earlier than the 1955 Holy Week and Easter Triduum changes exist, including hand missals for the laity attending Mass, include the St. Bonaventure Press facsimile of the 1945 St. Andrew's Daily Missal and the Omni/Christian Book Club facsimile of the 1945 Father Lasance Missal (originally published by Benziger Brothers).

See also

- List of communities using the Tridentine Mass

- Sacred language

- Western Rite Orthodoxy

- Pre-Tridentine Mass

- Communion-plate

- Ad orientem (direction the priest stands, as opposed to Versus populum)

References

- BBC: Tridentine Mass

- "About the Traditional Latin Mass". Traditional Latin Mass Community of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- In this context, "typical edition" means the officially approved edition to whose text other printings are obliged to conform.

- Angelus A. De Marco, O.F.M., "Liturgical Languages" in The American Ecclesiastical Review

- Council of Trent, session of 4 December 1563

- These regions included those in which a variant of the Roman Rite, called the Sarum Rite, was in use for more than the minimum required time. On a few recent occasions Roman Catholic prelates have used this variant as an extraordinary form of celebrating Mass. However, like most of the other regions and the orders concerned, the Sarum Rite areas have adopted the standard Roman Missal. The most important non-Roman liturgies that continue in use are the Ambrosian Rite, the Mozarabic Rite and the Carthusian Rite.

- George J. Moorman, The Latin Mass Explained (TAN Books, 2007)

- Pope Benedict XVI, Letter to the Bishops on the occasion of publishing Summorum Pontificum

- Code of Canon Law, canon 928

- Instruction Redemptionis Sacramentum, 112

- Summorum Pontificum, articles 2 and 4

- Summorum Pontificum, article 5

- Letter of Pope Benedict XVI

- Pope Benedict spoke of it instead as "an" extraordinary form. While in English, "extraordinary" often has laudatory overtones, its meaning in canon law is illustrated by its use with reference, for instance, to "the extraordinary minister of holy communion" (cf. canon 910 §2 of the Code of Canon Law).

- Summorum Pontificum, article 10 speaks of celebrations "iuxta formam antiquiorem ritus romani" (in accordance with the older form of the Roman Rite).

- Krmpotic, M.D. (1908). "Dalmatia". Catholic encyclopedia. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

The right to use the Glagolitic [sic] language at Mass with the Roman Rite has prevailed for many centuries in all the south-western Balkan countries, and has been sanctioned by long practice and by many popes.

- Japundžić, Marko (1997). "The Croatian Glagolitic Heritage". Croatian Academy of America. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

In 1886 it arrived to the Principality of Montenegro, followed by the Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, and the Republic of Czechoslovakia in 1920, but only for feast days of the main patron saints. The 1935 concordat with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia anticipated the introduction of the Slavic liturgy for all Croatian regions and throughout the entire state.

- "Inter Oecumenici, Sacred Congregation of Rites". 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- Manlio Sodi, Achille Maria Triacca, Missale Romanum, Editio Princeps (1570) (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1998) ISBN 978-88-209-2547-5

- Missale 2002

- Summorum Pontificum, art. 5

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacrament (2004-04-23). "Redemptionis Sacramentum". Retrieved 2008-03-25.

Mass is celebrated either in Latin or in another language, provided that liturgical texts are used which have been approved according to the norm of law. Except in the case of celebrations of the Mass that are scheduled by the ecclesiastical authorities to take place in the language of the people, Priests are always and everywhere permitted to celebrate Mass in Latin

- Thompson, Damian (2008-06-14). "Latin mass to return to England and Wales". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- Medieval Sourcebook; Pope reformulates Tridentine rite's prayer for Jews

- Letter to the Bishops on the occasion of the publication of Summorum Pontificum

- "Quo primum". Retrieved 2008-03-25.

We decided to entrust this work to learned men of our selection. They very carefully collated all their work with the ancient codices in Our Vatican Library and with reliable, preserved or emended codices from elsewhere. Besides this, these men consulted the works of ancient and approved authors concerning the same sacred rites; and thus they have restored the Missal itself to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers. When this work has been gone over numerous times and further emended, after serious study and reflection, We commanded that the finished product be printed and published.

- The Mass of Vatican II

- The Mass of the Consilium and the Mass of the Ages

- God Was Worshipped Here Today

- Meditation before Holy Mass

- Is the Novus Ordo Mass Actually the Indult Mass?

- Priories of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

- The Mass of the Apostles

- Cf. Extract from a Letter to a Philippine Mayor

- Braga - Capital de Distrito

- "Just after the Council of Trent, the study 'of ancient manuscripts in the Vatican library and elsewhere', as Saint Pius V attests in the Apostolic Constitution Quo primum, helped greatly in the correction of the Roman Missal. Since then, however, other ancient sources have been discovered and published and liturgical formularies of the Eastern Church have been studied. Accordingly, many have had the desire for these doctrinal and spiritual riches not to be stored away in the dark, but to be put into use for the enlightenment of the mind of Christians and for the nurture of their spirit" (Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine).

- ISBN 88-209-2547-8; publisher: Libreria Editrice Vaticana; introduction and appendix by Manlio Sodi and Achille Maria Triacca

- Introduction to the reproduction of the editio princeps, pages XXVI-XXX

- Introduction to the reproduction of the editio princeps, pages XXI

- Solemn Papal Mass. See further The Tridentine Mass by Paul Cavendish

- Apostolic Constitution Si quid est

- Missal in Catholic Encyclopedia

- Divino afflatu

- Mysterii Paschalis and Ordorecitandi website Archived 2004-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Richard Breyer, "St. Joseph & the Mass" in Catholic Digest". Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- K.P. Harrington, Mediaeval Latin (1925), p. 181

- Pope Benedict XVI's motu proprio Summorum Pontificum

- "The Missal published by Paul VI and then republished in two subsequent editions by John Paul II, obviously is and continues to be the normal Form – the Forma ordinaria – of the Eucharistic Liturgy" (Pope Benedict XVI's letter to the bishops on the occasion of the publication of Summorum Pontificum).

- Their dislike of the 1962 Missal is expressed for instance in a list of differences prepared by Daniel Dolan.

- Tridentine Community News, 11 March 2018

- "The Collaborative International Dictionary of English v.0.48". 1913. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- Chapman, John (1908). "Didache". Retrieved 2008-03-25.

Let no one eat or drink of the Eucharist with you except those who have been baptized in the name of the Lord.

- It is an additional ceremony, not part of the Mass itself, and in the Tridentine Missal is given only in an appendix.

- Text of Mass of the Catechumens

- Douay-Rheims translation

- Douay-Rheims translation of Psalm 84 (85)

- Rubrics V

- Text in Latin and English

- Summorum Pontificum, article 6

- The Rubrics of the Missale Romanum 1962: VI. The Epistle, the Gradual, and everything else up to the Offertory

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 66

- Text of Mass of the Faithful

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Santus

- Mass of the Faithful - The Canon

- Diptych

- Definition of "oblation"

- "Ab eadem parte Epistolae paretur cereus ad elevationem Sacramenti accendendus" (Rubricae generales Missalis, XX)

- Mass of the Faithful - Closing Prayers

- In pre-1962 editions of the Roman Missal, only the first four words, "Domine, non sum dignus", were to be said in the slightly audible voice.

- Ritus servandus, X, 6 of the 1962 Missal

- "Latin Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2015-06-09. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- Manlio Sodi, Achille Maria Triacca (editors), Missale Romanum: Editio Princeps (1570) (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1988 ISBN 978-88-209-2547-5), pp. 27–36

- Orationes ante Missam

- Douay-Rheims Version

- Orationes post Missam

- Allocution Indictam ante of 30 June 1930, in Acta Apostolicae Sedis 22 (1930), page 301

- Instruction Inter Oecumenici, 48 j

- Pope Pius X said: "If you wish to hear Mass as it should be heard, you must follow with eye, heart, and mouth all that happens at the altar. Further, you must pray with the Priest the holy words said by him in the Name of Christ and which Christ says by him" (The Daily Missal and Liturgical Manual from the Editio Typica of the Roman Missal and Breviary, 1962, Baronius Press, London, 2004, p. 897).

- They gave responses to "Kyrie eleison", "Dominus vobiscum", "Per omnia saecula saeculorum", the Gospel reading, the "Orate Fratres", "Sursum Corda", "Gratias agamus Domino Deo nostro", the conclusion of the Lord's Prayer, the "Pax Domini sit semper vobiscum" and the "Ite Missa est"

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Conventual Mass (Mass of a religious community) on a Vigil, such as that of Easter, was celebrated after None, at which point the fast could be broken (see Rubricae generalis Missalis, XV, 2). Though None was in origin an afternoon prayer, it was then celebrated in the morning. Similarly, Lauds, which was originally a morning prayer, was commonly celebrated in choir on the evening before, as in the office of Tenebrae. "Private Masses" (Masses celebrated by a priest without a congregation) could, even on days of fast, be celebrated at any hour from dawn to noon (see Rubricae generalis Missalis, XV, 1). Most celebrations of the Easter Vigil were in the form of private Masses, since concelebration was not allowed.

- The Pius X and John XXIII Missals Compared

- Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy

- Tres abhinc annos

- Missale Romanum

- Pope Benedict XVI, who has several times deplored departures on private initiative from the rite of Mass established in the 1970 revision of the Roman Missal has declared this contention unfounded, writing: "There is no contradiction between the two editions of the Roman Missal. In the history of the liturgy there is growth and progress, but no rupture. ... Needless to say, in order to experience full communion, the priests of the communities adhering to the former usage cannot, as a matter of principle, exclude celebrating according to the new books. The total exclusion of the new rite would not in fact be consistent with the recognition of its value and holiness" (Letter to the Bishops on the occasion of the publication of the Apostolic Letter motu proprio data Summorum Pontificum).

- A Short History of the SSPX Archived 2009-10-15 at the Wayback Machine